It’s the lightest and fastest series production bike Ducati has ever built, Jonny Rea and Kawasaki will need to watch their backs

2019 represents a watershed moment for Ducati, and indeed for Superbike racing in general. That’s because for the first time ever in the past 31 years since the World Superbike Championship began in 1988, there’ll be no desmo V-twin Ducati on the grid when the series kicks off at Phillip Island in February. Indeed, for the first time ever will there be no twin-cylinder motorcycles of any kind – and all the bikes on the grid will moreover have one-litre engines for the first time since 2008, when the FIM lifted the capacity ceiling for twins to 1200cc, against 1000cc fours.

That’s because Ducati has finally ended its line of desmo V-twin racers stretching back to 1972, when Paul Smart won the Imola 200, the Italian manufacturer’s debut race with a 750cc desmo V-twin. Fourteen World Superbike titles later – the last of them won as long ago as 2011 by Carlos Checa with a 1098R – Ducati has now finally produced a four-cylinder model for Superbike racing. And it’s based on its Desmosedici V4 MotoGP contender originally introduced back in 2002, with the latest version of which Andrea Dovizioso has been runner-up in the past two MotoGP World Championships to the Marquez/Honda duo.

That Desmosedici technology was already brought to the mass production marketplace one year ago with AMCN’s recently crowned 2018 Motorcycle of the Year, the Panigale V4 S, whose 1103cc motor however made it ineligible for Superbike racing. But at the EICMA show in Milan last November, Ducati unveiled its first-ever four-cylinder street-legal Superbike, the 998cc Panigale V4 R costing Euro 39,900 in Italy. WSBK rules impose a Euro 40,000 price cap in the country of origin for homologated models (which must be fully streetlegal, hence the V4 R is Euro-4 compliant, complete with a catalyst in its titanium stock exhaust), as well as a minimum of 125 examples to be built before the first race, 250 by the end of the first year, and 500 by the end of the second.

In order to ensure enough bikes will have been built before WSBK 2019 kicks off here on Aussie soil the last weekend in February, production will begin in January of what is Ducati’s most powerful production roadbike ever made, delivering 162kW (218hp) at 15,250rpm in streetlegal guise – 2250rpm higher than the 157.5kW (214hp) V4 S – with 112Nm of torque peaking at 11,500rpm from a motor rev-limited to 16,500rpm in top gear, or 16,000rpm in other ratios.

Stick on the Akrapovič race exhaust, and power rises to 172kW (234hp), on a bike weighing 193kg with water, oil and a full 16-litre aluminium fuel tank, or 172kg dry (186kg ready to race). That’s an amazing 1.36hp/kg – close to the 215hp/156kg Ducati 1299 Superleggera 1.38hp/kg, currently the highest power-to-weight ratio of any production roadbike yet.

But Ducati doesn’t regard the V4 R as a limited-edition special, like the 500-off Superleggera, which sold out immediately in 2017 despite costing exactly double the price of the V4 R, with half the number of cylinders.

“We anticipate building at least 1000 examples of the V4 R in 2019,” says Ducati’s Product Manager, Paolo Quattrino. “While of course it’s a very expensive model, we believe that the high level of technology and the outstanding performance will attract many customers – not only committed ducatisti, but we hope too conquest customers from other brands. So this will not be a limited-edition model.”

Just three weeks after its EICMA debut, Ducati allowed just one dozen journalists from all over the world to join factory WorldSBK riders Chaz Davies and Alvaro Bautista for a day aboard the bike at the Jerez circuit in the sunny south of Spain. Well, that was the idea anyway, but the day did not start well, with rain, mist and a wet track. But soon after midday the track dried up, and so that afternoon I spent 35 laps aboard the V4 R gradually becoming more and more – and more, and more! – impressed by it. This is quite some motorcycle.

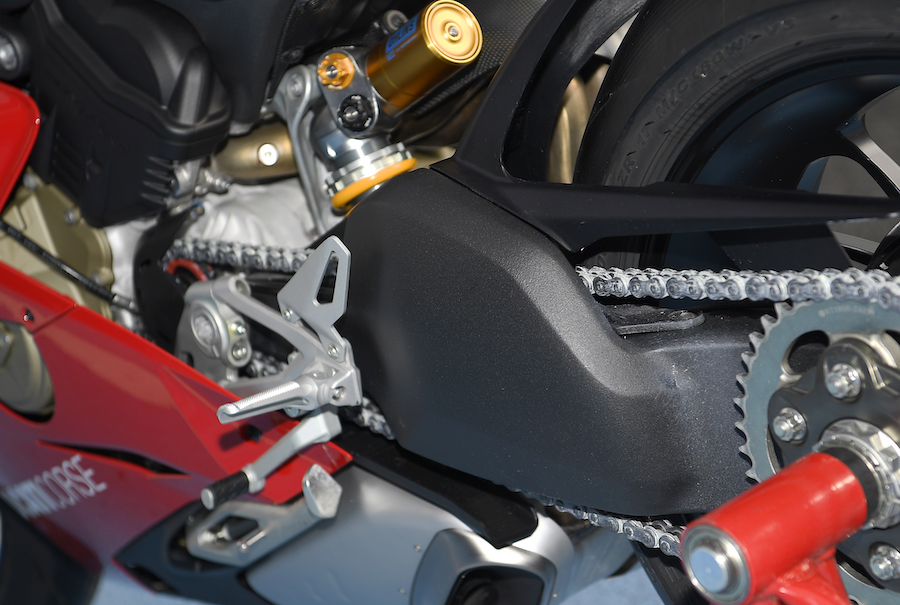

For while it shares the same technical basis as the more prosaic but still super performing V4 S, this is a very different motorcycle to ride. Firstly, of course, because of the engine which, thanks to its shorter-stroke format measuring 81 x 48.4mm – as opposed to 81 x 53.5mm for the S-model (remembering that an 81mm cylinder bore is the largest diameter allowed for Superbike racing) – already has a greater appetite for revs, even before the V4 R’s adoption of a 1.1kg lighter backwards-rotating forged steel crankshaft, plus titanium conrods and 34mm intake valves (the 27.5mm exhaust valves are steel).

This not only lifts the revs ceiling to that amazing 16,500rpm limit, but also allows the V4 R to pick up revs harder and faster exiting a turn. It’s aided in that by the same Twin Pulse firing order as on the GP16 MotoGP bike, obtained via a 70-degree crankpin offset together with a 90-degree V4 cylinder angle, with the two left cylinders essentially firing closely together, followed by the two right ones in a 0°, 90°, 290° and 380° firing order. This makes the V4 R sound just like the MotoGP Desmosedici V4, complete with the same chilling high-pitched hollow-sounding roar from the dual exhausts, which you’re very well aware of when riding the bike, as well as when standing trackside.

Yet despite breathing through a quartet of huge elliptical throttle bodies (equal to 56mm in diameter), the desmo V4 R motor is highly tractable, even friendly, in the way it makes power. You could honestly imagine riding this bike to the shops, it pulls so cleanly from low down, barely off the 1500rpm idle speed, with zero transmission snatch and only a little use of the light-action, dry, slipper clutch. Yes, for the first time in many years, the trademark Ducati rattle is back with the clutch plates kissing each other at low revs, without the oil bath they’d otherwise be sitting in to quieten them down. Power builds in a totally linear way, until just above 8500rpm – when 80 percent of maximum torque is already available, only halfway to the redline – things start to happen a lot faster.

Read the full story in the current issue of AMCN (Vol 68 No 13) on sale now

Test Alan Cathcart Photography Gigi Soldano & Thomas Maccabelli