Legendary road racing photographer stands up and says what many others are thinking

When bike fans think of road racing, the Isle of Man TT is usually the first race that comes to mind. The Manx races is the most famous between-the-hedges event in the world but there are many more closed public roads meetings scattered around the globe. Each season I try to visit a race that I haven’t seen before and this summer I added three new events to my CV.

The first was a new Irish race, the Enniskillen 100, which was making its debut on the Irish National championship calendar in July. A week later I travelled to the Czech Republic for the 10th anniversary celebrations of the Frantisek Bartose Memorial races in Ostrava. And in August, a trip to Wales to see the Aberdare Park races.

Over the past couple of decades, I’ve religiously attended the national and international meetings in Ireland, visited the TT, the Southern 100, Manx Grand Prix/Classic TT, Macau GP and many of the Scarborough meetings. As an antidote from this seasonal sequence I’ve made regular trips to places like Frohburg, Imatra, Horice and the wonderfully loose La Baneza races in Spain.

Immersing yourself in these down-to-earth events can feel as if you’ve turned the clock back 30 or 40 years to a time when a lot of bike racing still took place on public roads.

It was 66 years since a road race, also called the Enniskillen 100, was last run in County Fermanagh. This year’s new circuit was a 4.8km triangle of country roads that included plenty of variation. Bumpy, narrow laneways, where overtaking was almost impossible, gave way to a super-fast stretch of smooth, asphalted highway.

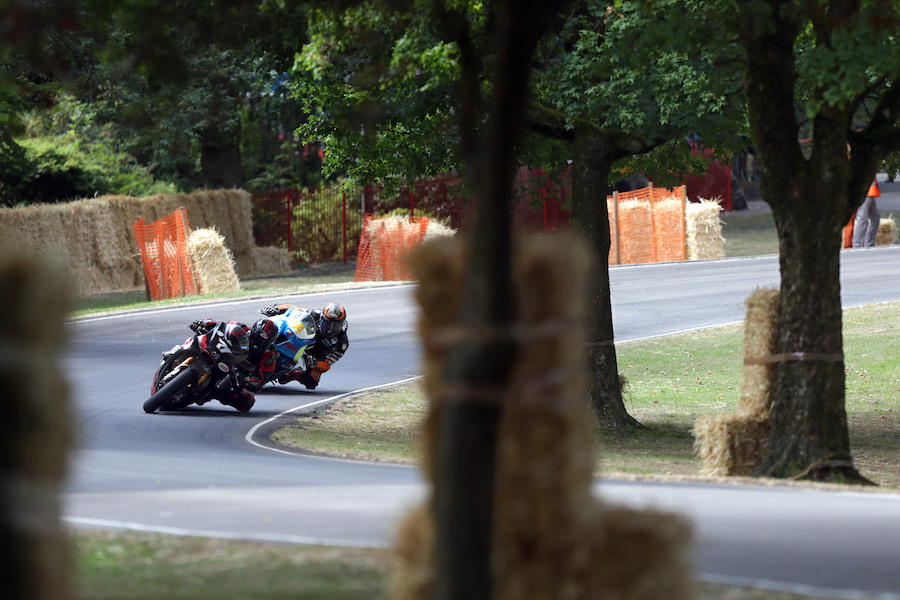

Aberdare’s races take place on a track running through the small Welsh town’s public park. The scent of roses mixed with two stroke fumes as the bikes blitz past the duck pond racing their way around the tight 1.5km track.

Factory chimneys belching another kind of fumes formed the backdrop to the Ostrava races in the eastern corner of the Czech Republic. The 3.4km circuit makes its way past pubs and cottages on the edge of the former communist country’s most industrialised city. Unlike the other Czech road meetings at Horice and Terlicko, Ostrava is not part of mainland Europe’s International Road Racing Championship (IRRC).

With little start or prize money on offer, none of these events attracted any of the road racing’s superstars. I had never heard of any of the Czech, Polish or Slovenian racers who raced at Ostrava but with a pint of local beer costing just 90 cents, there was plenty of noisy encouragement from the hordes of flag waving spectators.

TT racers Derek McGee and Adam McLean provided most of the entertainment in Fermanagh with McGee winning five races, including both superbike events, on his Kawasaki ZX-10R.

Dan Cooper was the winner of the Welsh Open feature race at Aberdare, with Joey Thompson, local specialist Jay Bellars-Smith and former Manx Grand Prix winner John Simpson providing the main opposition. Still recovering from injury, John McGuinness performed several parade laps.

All three meetings included classes for a mix of modern and vintage machinery. Aberdare had 50cc and 80cc bikes running alongside colourful sounding Golden Era and Sound of Thunder classes. Everything from a 1960s-era BSA Gold Star to modern Triumph 675cc triples were out on track. Only Enniskillen included superbikes in its programme, but every meeting hosted races for Classic, 125cc, Supertwin and 600cc machines.

The fine summer of 2018 provided glorious sunshine for the spectators at all three meetings. No official attendance figures were available but a rough estimate would suggest several thousand people turned out at each meeting over both days.

The Welsh and Czech races charged admission for the privilege, with Aberdare demanding a $25 entry fee per person plus an extra five bucks for a race programme. Road closing orders in Northern Ireland prohibit race organisers from levying such charges. Spectators were encouraged to purchase a programme instead, at a steep $27, but there didn’t appear to be many takers.

London policeman Alex Smith used to race at Aberdare but he now returns to his home village each August to help his father Derek run the event. Race sponsors augment the Welsh event’s admission charges with all the profits being ploughed back into the races.

“We get a lot of support from the local Council but no finance,” Alex explained. “Which means the races have to be run as a commercial operation.”

After a wash-out in 2017, the organising club had struggled to meet its costs but Alex was delighted with the large gate this year. He felt the Welsh meeting had benefitted a little from this season’s cancellation of racing at Scarborough. Ostrava also enjoyed a more positive 2018.

“Each year might be the last,” Milan Kubin, a photographer and journalist who also helps promote road racing in the Czech Republic, told me ominously before racing began.

That kind of doom and gloom seems to hang over so much of road racing. Perhaps the calls for the sport to be banned that often come after tragedies has fostered this fearful outlook and led to what feels like a siege mentality amongst sections of those who run the sport.

The Czech organisers said they needed a big crowd to encourage the city government to maintain its level of funding of the races. The sunshine helped deliver the required result.

Public funding also underpinned the Enniskillen races. The local Council pumped in money to get the races off the ground in a hope of boosting local tourism. The costs of organising the race are high. Over 700 pieces of flexible foam protection lined fences, telegraph poles and stone walls around the Enniskillen course. One section was considered so dangerous a tunnel of huge bales were strung out on either side of the narrow road for literally hundreds of yards.

Safety provisions at Aberdare and Ostrava was more rudimentary. It was disturbing to see parcel tape being used to attach straw bales to a statue that stood in the line of fire at the entrance to the Welsh park. More bales were deployed around the bases of dozens of huge trees. Old tyres, painted red and white, plus bags of plastic bottles were tied to trees and signs around Ostrava’s 3.4km course. It seemed ironic that Enniskillen, the only meeting of the three that didn’t have an admission charge, had obviously spent so much more money than the other clubs on protective measures.

The Irish club says it hopes to run again in 2019 but the future of these small events, run by a band of enthusiastic and unpaid volunteers, remains precarious. In a hand-to-mouth existence that involves a constant battle to balance rising costs against uncertain incomes, a single day of lousy weather can spell instant disaster.

It would be easy to see the circumstances of these grassroots events as simply part of their unique culture. Geography certainly seems to make little difference in the experience of the UK races and their Czech counterpart.

What struck me though during my recent visits was just how many similarities there are among these smaller races and their high profile international cousins. Where there are disparities they seem more of scale than content.

Minimal protection is not confined to Aberdare or Ostrava. The same foam recticel is deployed only sparingly around the TT’s Mountain Course and it is non-existent on Macau’s ludicrously dangerous Armco lined track.

Likewise, the North West 200 and Ulster Grand Prix, Ireland’s leading international events, face relentless financial pressure and have both been brought to their knees recently by bad weather that forced the abandonment of racing. Insurance costs continuously spiral upwards for road racing. In Northern Ireland even more pressure is set to be heaped on race bosses if proposals to bill race organisers for the costs of policing are introduced.

A close and vital relationship exists between the smaller road races like Enniskillen and the sport’s major events at the TT and North West 200. Many TT winners have had their first between-the-hedges outings on little byways like the Fermanagh lanes. Peter Hickman might have been plucked from the BSB series to TT glory, but Michael Dunlop served his road racing apprenticeship on road circuits very similar to Enniskillen.

New Mountain Course recruits have been thin on the ground in recent seasons and now racing has disappeared at Scarborough with the cancellation of all the 2018 meetings. Guy Martin, Dean Harrison, Ivan Lintin and the late James Cowton all learned their trade at Oliver’s Mount and the permanent loss of England’s only road-racing venue will have a significant impact. And after a year when we have suffered a string of tragedies involving some of the sport’s biggest names and rising stars, that impact could cut even deeper.

For those who continue to race the roads, these problems are usually seen as being issues for others to debate as they face the more immediate challenge of staying safe in the world’s most dangerous sport.

The angles of lean and corner speeds by the fastest riders competing at Aberdare, Enniskillen and Ostrava were breathtaking given the solidity of the obstacles that lay in wait at the very edges of the tarmac.

Although there may be a huge differential in speeds between tracks like the TT’s Mountain Course and Aberdare, hitting a tree with only the scantiest of protection will probably have the same outcome whether you wallop into it a 100km/h or 250km/h.

Such considerations are usually met with the same nonchalant response by road racers.

“If you thought about it, it probably would put you off. So you don’t think about it,” remains the stock answer.

Thankfully there were no serious crashes or injuries at Aberdare, Enniskillen or Ostrava in 2018.

Ostrava

The industrial city of Ostrava is 370 clicks east of the Czech capital, Prague, close to the Polish border. The annual road races take place each July and are named in memory of local hero, Frantisek Bartose, a factory CZ rider in the 1950s world championships.

There is a thriving road racing scene in the former Communist bloc country, with Horice and Terlicko hosting rounds of the International Road Racing championship. Two Czech racers, Marek Cerevny and Kamil Holan, are stars of the series and have both competed at the TT.

Aberdare Park Road Races

Races have been held on the parkland circuit of the South Wales town since the 1950s and was the venue for the first ever live television broadcast of bike racing in 1955.

Illustrious names from the history of British bike racing such as Mike Hailwood, John Surtees, Bob McIntyre, Phil Read and John Cooper have all competed at the Aberdare Park Road Races and four-time WorldSBK champ Carl Fogarty is a former lap record holder.

www.aberdare-park-road-races.co.uk

Enniskillen 100

The County Fermanagh race is the newest addition to the series of smaller Irish events which make up the Irish National Championship. They also include Cookstown, Tandragee and Armoy in Northern Ireland plus Skerries, Faugheen, Walderstown and the East Coast races (Killalane) in the Republic.

Situated near the village of Arney, the inaugural event paid tribute to the county’s best known road racer, Richard Britton. Britton died in a crash at Ballybunion in 2005. His sons rode some of his former race bikes in a tribute lap during the 2018 event.

www.enniskillenroadraces.co.uk

Words & Photography Stephen Davison