The first thing to learn is that the quickest way from A to B is via X, Y and Z

As you marvel at the dramatic vistas in the Dakar coverage on the TV, it’s near impossible to believe the prowess of the riders; particularly when you consider not a single one of them knows where they’re going; or what danger lurks over the next crest. There’s no GPS screen, no highlighted route and no helpful Siri informing them of when to make a U-turn.

All the riders have mounted on the handlebar is a paper scroll called a roadbook – certainly a misnomer when they’re several kilometres away from the nearest track. Often they’ve little more information than a compass bearing to follow despite the rugged terrain ahead. Then comes the relief when the light on their Sentinel tracker confirms they’ve reached a hidden waypoint, only to check the scroll to ascertain the next compass bearing.

In such conditions – deviating around rocky outcrops, immense washouts, deep bulldust and large clumps of camel grass – it’s impossible to follow a straight line; which is where gut instinct counts and cross-country experience comes into its own.

Even when more explicit instructions are provided there’s always room for interpretation – all at high speed over a surface likely to catapult the rider into oblivion at any moment. It isn’t just a matter of matching the odometer and the roadbook with the terrain ahead.

To render the route instructions easier to interpret, each rider spends up to hours every night marking up their own route map (below) so as to quickly comprehend what to do when there’s a ‘DANGER 3’ ahead. Aussie Rod Faggotter – the only Yamaha Team rider to finish the 2018 Dakar – is living proof that he’s using the right brand of highlighter and demonstrated to AMCN the secrets of his success. If you look closely, there are four changes of compass bearings, two single cautions, a double caution and a triple caution in less than 20km.

Bear in mind, a rider has maybe one second to comprehend each instruction and often less than two seconds more to react. And that most accidents are caused by conditions that are not shown in the roadbook. The roadbook only provides knowledge of the known knowns, so riders must be aware of the known unknowns.

To this day neither Toby Price nor Sam Sunderland knows exactly what brought their title defences undone. All Toby recalls of his 2017 crash is that, “I was full gas in deep sand along a riverbed at maybe 140-145km/h and hit something in the sand. I remember hearing valve bounce then waking up to a smiling medico in La Paz hospital waving an X-ray who said ‘Tobee, zee operation ees good’.”

It’s easy to comprehend why competitors agree successful cross-country rallying is 80 percent navigational skills and 20 percent riding skills.

The Dakar moved to South America 10 years ago, and its terrain is just as challenging as Africa

Paper plains

Now imagine trying to follow this at 150km/h through some of the harshest environments in the world

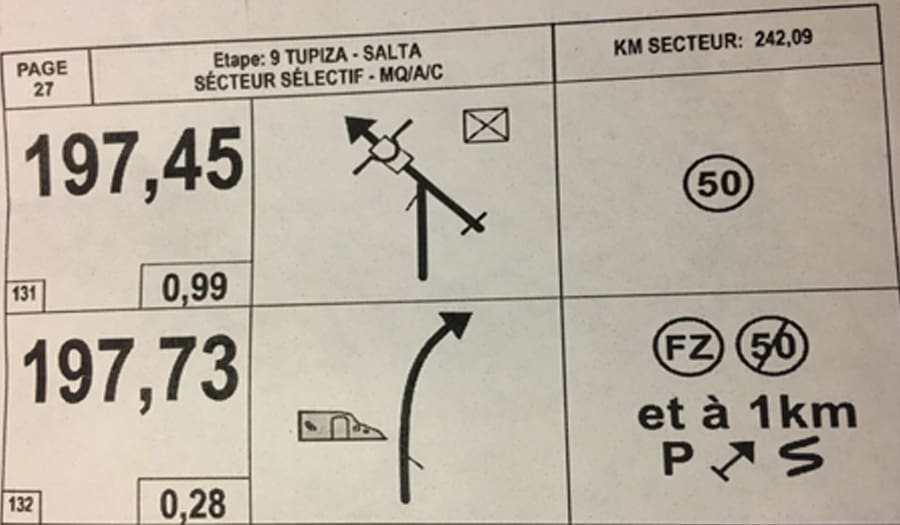

In the following example, the instruction is to veer left at about 45°, over a culvert in a 50km/h ‘quiet zone’ (or suffer a one minute penalty for each km over this limit). There’s some sort of dwelling indicated (top right) to provide orientation. Then 280 metres further on – just past the ruins on the left – the instruction is to veer right and apply full gas; the quiet zone has finished. It all seems simple except that in one kilometre the track heads uphill into curvas peligroso or dangerous curves.

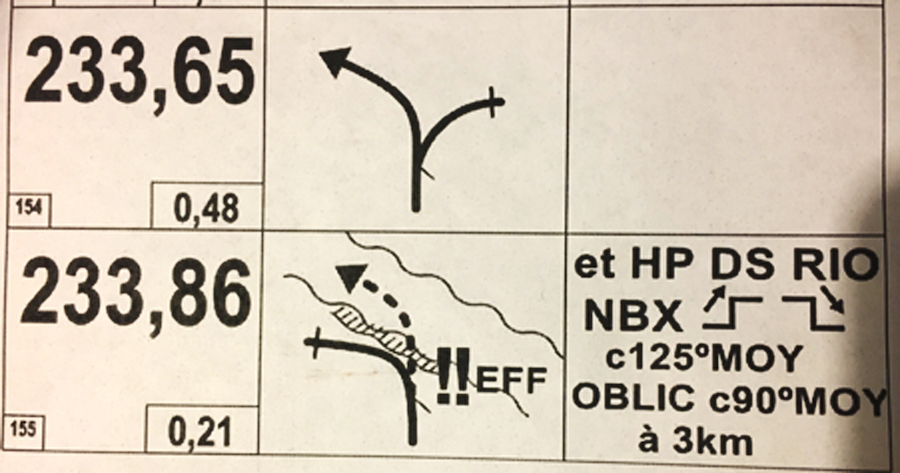

Then the next instruction is very simple – just study the diagram. At 233.65km take the left fork then 210 metres later leave the track and descend over the very rough erosion ruts – note the Double Danger – into a dry riverbed. No problem! Except that no matter the twists in the riverbed, the instruction is to follow a compass bearing of 125°. All whilst noting there are numerous up and down sharp edged ledges – only some of which may be seen by the naked eye. Then a little further on (if you’ve done your mental arithmetic properly, that will be at 236.86km) the instruction is to switch to compass bearing 90°; always remembering that a reduction in degrees means a turn to the left and an increase means a turn to the right – except if you’re anywhere near 360°, where a simple mistake will send you in an endless loop.

Words & Photography Peter Whitaker