Guess what? It turns out old-fashioned tech like air cooling and pushrods have a place in future motorcycles after all

As motorcycle emissions laws tighten it’s easy to find armchair experts who’ll confidently tell you that some of the internal combustion engine’s oldest technologies –air-cooling and pushrod-operated valvetrains – are living on borrowed time.

Technology and complexity are held on a pedestal for the endless year-on-year improvements in emissions and performance. Today’s mind-bogglingly intricate high-performance engines – replete with variable valve timing, four valves per cylinder, double overhead camshafts and a host of other tricks – are wonders of engineering. But despite constant suggestions that tightening emissions laws will consign anachronisms like air-cooling and pushrods to the same Room 101 that the two-stroke was sent to years ago, they staunchly refuse to be edged out of the market.

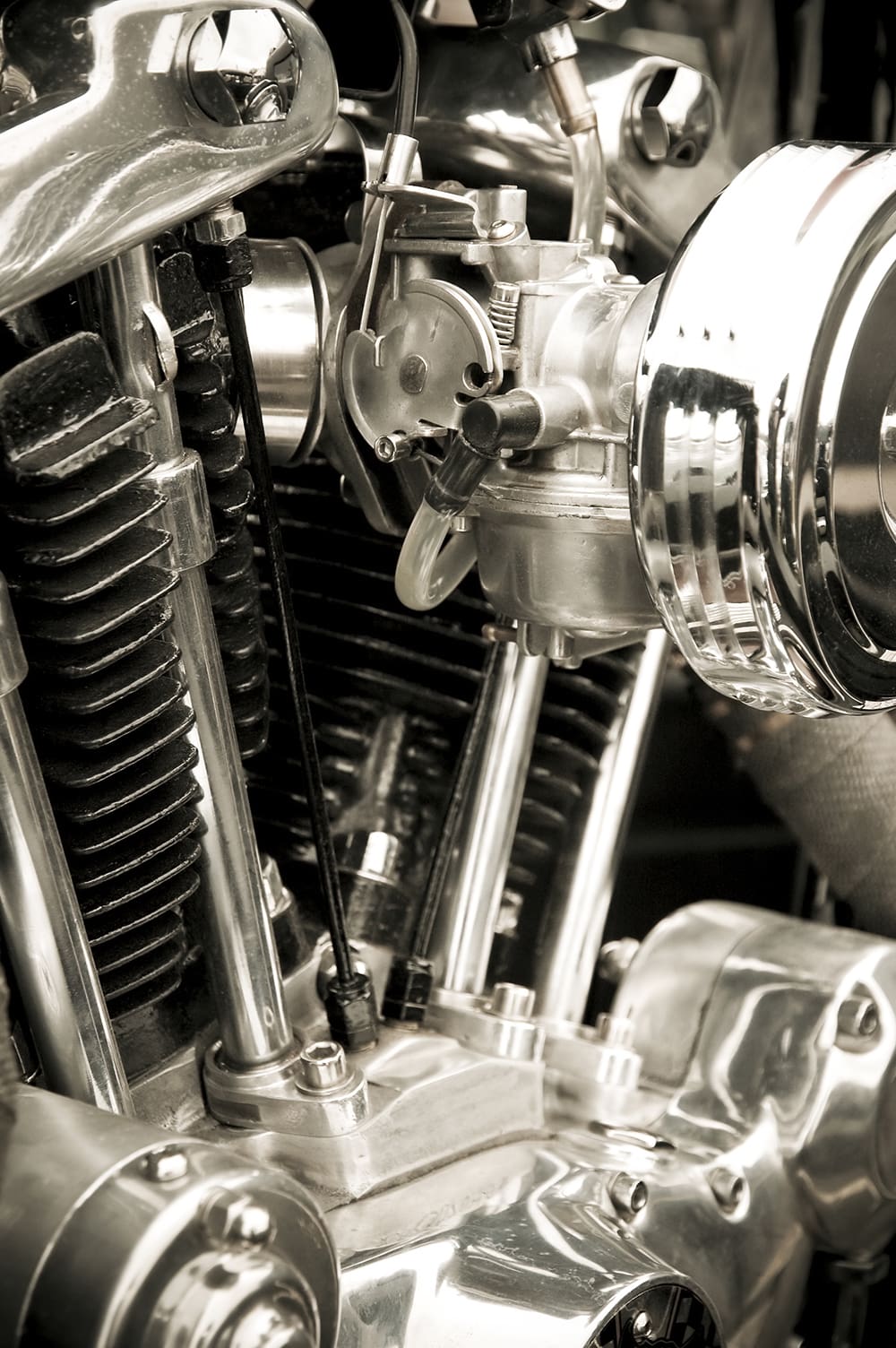

Indeed, one of the most significant new bikes this year uses both air-cooling and pushrod valve actuation. The engine in BMW’s upcoming R 1800 cruiser range has a design that would be as recognisable to a motorcyclist from 1920 as one from 2020. But why do these old ideas persist and do they really have a place in the modern world?

Demand and supply

When it comes to motorcycle engine design you’ll struggle to find anyone much more knowledgeable than Paul Etheridge, Head of Motorcycle Strategy and Business Development at Ricardo, which is a global strategic engineering and environmental consultancy that specialises in the transport, energy and scarce resources sectors. We asked him what makes air-cooled and pushrod motorcycle engines so tenacious.

“Air cooling is popular at the extreme ends of the market,” he said, “You’ve got big cruisers – mainly what we’d call ‘heritage or retro products’ that follow a company’s history where air cooling is part of their DNA – and at the other end of the spectrum there are mass-made vehicles in emerging markets, which like air-cooled engines because they’re cheap, simple and easy to maintain.

“The difference is that the smaller engines generally don’t have pushrod valvetrains. It’s not necessary to marry air cooling and pushrods, but in certain sectors it’s the norm; heritage products commonly use pushrod valvetrains (particularly in the US V-twin market), while smaller bikes for the mass markets generally have single overhead cam engines.”

Although it’s easy to equate out-and-out performance improvements with the advance of technology, the key to understanding the appeal of these old-school designs is recognising that power isn’t at the top of their list of priorities.

Considering the massive new BMW boxer engine, which will be revealed in all its glory later this year and uses both pushrods and air cooling, along with a huge capacity of around 1800cc, Paul Etheridge said: “There are advantages in an engine like that, where you want lots of torque and maybe not so much in terms of ultimate power output. That arrangement is very compact in terms of cylinder-head design, and aesthetically they look much better.

“Look at a modern superbike engine, evolved to produce incredible power at very high engine speed. The valvetrains have become much more complex, because that’s at the heart of getting power out of an engine; getting enough air into it and, since power is a function of speed, the rotational speeds have gone up and the valvetrain complexity has gone up as well. In doing that, the cylinder head has become taller and taller. The included valve angles have reduced, because then you can get a more free-flowing port arrangement under the valves. All these things have dictated how the engine geometry has changed. The quest for more power means rotational speeds have gone up, so you have big bores and small strokes so you can rev the engine higher, which means you have a shorter engine with a much taller cylinder head. That doesn’t look very nice, particularly in a cruiser, and it would be completely unsuitable from a torque curve point of view.

“So the big cruisers have gone the other way. They’ve generally gone to bigger capacities, but with a pushrod valvetrain so you can limit the height of the cylinder head and package a big engine into a motorcycle. They get the torque and power they need from the fact it’s a massive engine, not from revving them hard. They’ve also got a nice torque curve, and from a driveability point of view torque is more important than power.”

Power isn’t everything

It’s easy to look at the massive air-cooled, pushrod-valved twins offered by the likes of Harley-Davidson or Indian – the machines that BMW is firmly targeting with its new design – and mock their lack of power. It’s not unusual to find an engine of 1600cc or more that peaks at less than 75kW (100hp). That figure seems weak in a world of 200hp, 1000cc superbikes, but it’s an intentional trade-off that those firms choose to make, not a limitation brought on by a lack of engineering capability.

“A pushrod valvetrain has limitations because the valves are heavy, the pushrods and rockers are heavy and if you’ve got hydraulic lash adjusters, those elements are quite heavy, too. They’re relatively flexible as well, so what you do with the camshaft doesn’t relate perfectly to what happens at the valve. That ultimately limits the performance of the valvetrain and limits the speed you can rev the engine to.

“In modern overhead cam engines, the cams act directly on the valves or, on even newer versions, via finger-followers. This is all done to push the speed of the valvetrain up, reduce the mass of the individual components, and to improve the structural integrity of the valvetrain. Ultimately that means you can rev the engine harder before you start to have dynamic problems with the valvetrain, where effectively the springs go into surge and the valve doesn’t follow the camshaft. Valve bounce. Ducati’s Desmodromic system is a very old but very good solution to keeping the valvetrain under control because there’s no spring; the valve is both opened and shut by a rocker. But it’s an expensive system.”

But out-and-out power isn’t what a cruiser needs. Torque, giving the ability to lope effortlessly along in a high gear and get instant acceleration without changing down a gear or two, is far more important. For that sort of response, out-and-out engine capacity is the answer. That brings a new problem: how to fit the biggest engine possible into the limited space in a motorcycle’s frame.

Suddenly a pushrod valvetrain – roughly halving the height of the cylinder head compared to an overhead-cam solution – looks very attractive. The same goes for air-cooling, eliminating bulky components like the radiator, while simultaneously making for a cleaner, more classic-looking engine.

When it comes to the massive new BMW cruiser engine, Etheridge reckons there was no alternative to using pushrods. He said: “That boxer engine would not be possible with an overhead cam system on it. It’s big enough as it is, but you’d probably double the height of the cylinder head if you put in an overhead cam system. You wouldn’t be able to filter through traffic!”

Emissions advantage

Bar-stool experts will often suggest that these old-school engine designs, with air-cooling, pushrod valvetrains and two valves per cylinder, are living on borrowed time, and that emissions limits are going to force them into extinction. But Paul Etheridge reckons emissions rules aren’t a particular problem for them. On the contrary they have certain advantages over smaller, higher-revving designs.

“Air-cooled engines tend to take longer to warm up than their water cooled equivalents, but ultimately tend to run hotter. This needs to be considered when developing the emission control strategy, as this changes the engine-out emissions performance over the emissions test drive cycle. The engines have an advantage in that they’re relatively low specific output (in terms of bhp/litre), so the valve events aren’t that extreme,” he said, “With a high-performance engine you get a lot of valve overlap, where the intakes and exhausts are open at the same time, but that gives you a lot of unburned hydrocarbons getting into the exhausts. These big, lazy engines don’t suffer from that so much.

“Generally the superbike engines really struggle to get good air motion in the cylinder because the ports are designed so much to get as much air into the engine as you can it’s difficult to generate enough air motion to give good part-load combustion stability. On an engine in a lower state of tune you can design for a higher level of air motion in the cylinder – they call it ‘tumble ratio’ or ‘swirl ratio’ depending on the rotational axis of the motion – which will give you better part-load combustion, which improves emissions and your fuel consumption as well. So that’s actually a bit easier with a big cruiser engine.”

So what, exactly, is this all-important ‘air motion’?

“The design of the intake port is very critical to get the right air/fuel mixing in the cylinder. If you’ve got disorganised airflow, and the air’s just flowing all around the intake valve, you tend to get very poor combustion at part load. You might be okay at full power, with the throttle wide open, but at part load it will be very jerky because the combustion isn’t stable.

“If you can manage the airflow well and get the spark plug in the right place so you get good, stable combustion, you can improve all that and reduce your engine-out emissions as well. Some big bore engines also use two spark plugs per cylinder to further enhance part load combustion stability.”

It was this part-load airflow and intake/exhaust port overlap problem that was largely responsible for the demise of the two-stroke.

“At part load old two-strokes might only fire once every six or seven cycles, believe it or not,” said Etheridge. “The rest of the time the fuel is just going out of the exhaust without being burnt, so you get extremely high hydrocarbon emissions. Bad combustion chamber four-strokes aren’t as bad as that, but it’s the same principle; you’re not getting complete combustion every cycle, so fuel is going into the exhaust without being burnt.”

Far from being at a disadvantage, the cruiser engines that seem so old-fashioned might have an edge over the seemingly more modern, high-performance designs used in superbikes when it comes to meeting Euro-5 emissions limits.

Exhausting problems

Where the next generation of cruisers will be able to keep their air-cooled, pushrod engine designs, they will face a challenge from the fact that aesthetics are so important in that part of the market. In particular their designers are going to have to find a solution to packaging catalytic converters.

Tighter new emissions rules are forcing manufacturers to move their catalytic converters closer to the cylinder head, rather than hiding them in the silencers at the other end of the exhaust. We’ve already seen some creative solutions to the problem, notably Triumph’s latest Bonnevilles, which feature cats in front of the engine – where they can look like part of the motor itself – fed by blacked-out exhausts diverted from the main header downpipes. Once cleaned, the gasses are routed back into the normal exhausts. By using chrome dummy exhaust sections Triumph successfully creates the illusion of having pipes that run straight from the cylinder head to the silencer, drawing the eye away from the reality of the catalytic converter. We can expect to see many more solutions like that being adopted by cruiser manufacturers over the next few years.

VVT & cruiser engines

One possible advantage of pushrod engines is that it could be easier for them to adopt variable valve timing (VVT). They usually have just one camshaft, where an overhead-cam V-twin would have two or four camshafts, each needing a VVT system.

Companies including BMW and Ducati are rapidly embracing the idea of VVT to help get the most out of their latest engines and a recent patent from Indian shows it could be the first to adopt the same idea for a pushrod cruiser motor. But while it might not be hard to add variable valve timing to a pushrod engine, the benefits are comparatively slim compared to when the technology is used on higher-revving designs with more valve overlap.

“VVT is becoming more popular and I think with Euro 5 you will see a few more engines with VVT, as it gives a lot of advantages: emissions, driveability, torque curve shape, fuel consumption and combustion stability. Overall, VVT is a great technology and it may be something like Euro 5 that pushes it into the market more,” says Etheridge. “But with these big but low power cruiser engines, you don’t really need it.

“BMW’s [R 1250] boxer has VVT on it this year, but that engine is highly tuned – it’s not a cruiser powertrain, it’s a high-performance vehicle. It’s got to compete with things like the Ducati Multistrada, which also has variable valve timing. So that is a highly sophisticated engine with high specific output that needs good torque, good power, good driveability, and hence it has a lot of sophisticated features on it. Cruisers don’t need that. It’s a different requirement.”

Aren’t these old designs inefficient?

The combination of large engine capacity and relatively low power means it’s easy to jump to the conclusion that cruiser engines aren’t as efficient as more ‘modern’ layouts with DOHC cylinder heads and water cooling. But Paul Etheridge is quick to dismiss that notion.

“Power output is not a by-product of efficiency,” he said, “These engines are designed for purpose, and they’re quite efficient, actually. They’re relatively low-emissions engines. Because of what we’ve talked about – the valve timing requirements, the fact you don’t need massive specific power output, the fact they’re limited in terms of rotational speed by their bore/stroke and the pushrod valvetrain – cruiser engines are efficient at what they need to do.”

The demand for ever more power from a specific capacity, largely driven by racing regulations that put limits on engine size, has created the drive for more complex engines over the years.

“You can see trends as you go up in specific output,” Etheridge points out. “You can do a certain amount with pushrod valvetrains, and you can go a certain way with air cooling. The next step, if you want more specific output, might be to a single overhead camshaft design and maybe introduce some oil cooling as well, spraying it on the underside of the piston or having specific channels in the engine which are for cooling, not just lubrication.

“The Suzuki GSX-R is quite a good example. They had oil cooling for a few years, but when you go over a certain specific output, you still can’t get the heat out of the engine, so at some point you have to go water-cooled. And then the valvetrains become more sophisticated because to get more power you have to push the speed up, so you get double overhead camshaft, direct attack or finger-follower, or you start using exotic materials or more exotic valvetrains. That’s the evolution of the engine if you want to keep increasing specific output.

“But the market is changing now and these heritage/retro products are a reaction to the fact that people don’t want a 300km/h motorcycle made of plastic anymore. People want to look cool, go out and have fun, and these bikes are great for that. They look great but they’re relatively technologically simple.”

BMW’s new cruiser project, one of the most significant motorcycle investments in years from the firm and the basis of an entirely new range that will bring the firm into competition in a market that it’s never really ventured into before, tells us that air cooling and pushrod valvetrains are far from dying technologies. In fact, as the motorcycle market becomes more diverse than ever before, they could be on the verge of a renaissance.

Words Ben Purvis Photography AMCN Archives & BP