Mount Panorama played host to one of Australia’s greatest ever road races. John Woodley going head-to-head with Graeme Crosby and Ron Boulden

John John Woodley’s legendary Unlimited Grand Prix duel with Graeme Crosby and Ron Boulden on larger machinery remains etched in Bathurst folklore. All three were riding a different motorcycle, with the 1978 Australian 350 champion Ron Boulden making just his second appearance on a Yamaha TZ750E, Crosby was riding Gregg Hansford’s water-cooled factory TKA Kawasaki KR750 triple and John Woodley riding on board the latest Suzuki RG500 Mk IV rocket ship. Adding to the intrigue, Boulden hailed from Sydney, while his two Kiwis challengers were raised in Blenheim, New Zealand.

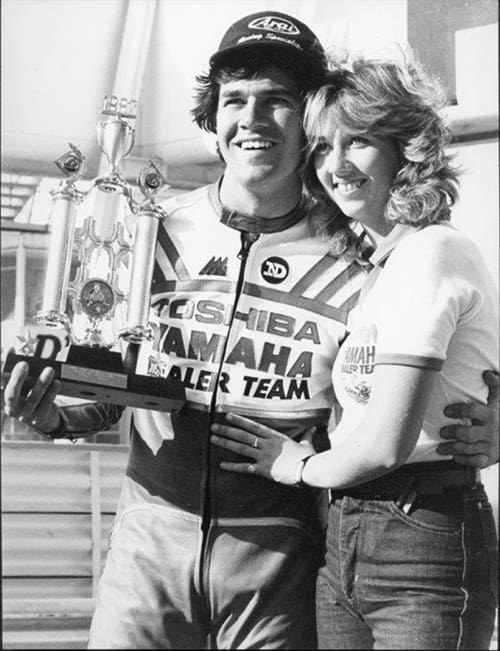

Croz swaps his helmet for a top hat for a Heron Suzuki publicity shot

Practice

During Thursday practice, Woodley lapped 3.59 seconds faster than he did three years previous, but then seized the expensive Team Hunter Suzuki RG500, as did Boulden on his Welbank TZ750E, several times. Boulden also suffered tyre troubles, with a new rear Goodyear blistering down the middle. Incredibly, he still qualified on the front row with a seized engine.

“It seized at the end of Conrod Straight and I had to pull the clutch in and coast around and over the line – so I only got one lap in qualifying!” Boulden recalls.

Friday night before the race, Boulden’s team led by Warren Willing were desperate for answers to the seizures. A non-return ball-valve in the fuel tank breather was fitted at Calder Park to stop a leaking fuel issue, but it was becoming stuck as Boulden raced over the humps at Conrod causing a vacuum inside the tank, a loss of fuel, and a subsequent seizure.

“So we took out the ball – it was the last thing we could think of. It was the fifth or sixth rebuild and it was the only logical thing, so we went back and jetted it correctly, and it came to our first race.”

Crosby’s version of practice, who was racing several machines that weekend, included some pretty hefty boozing.

“It was always a party at Bathurst!” Croz says. “I partied with Ross and Ralph Hannan and all the sidekicks who hung around. Once we got the KR750 jetted and geared right it ran well, there were no problems at all.”

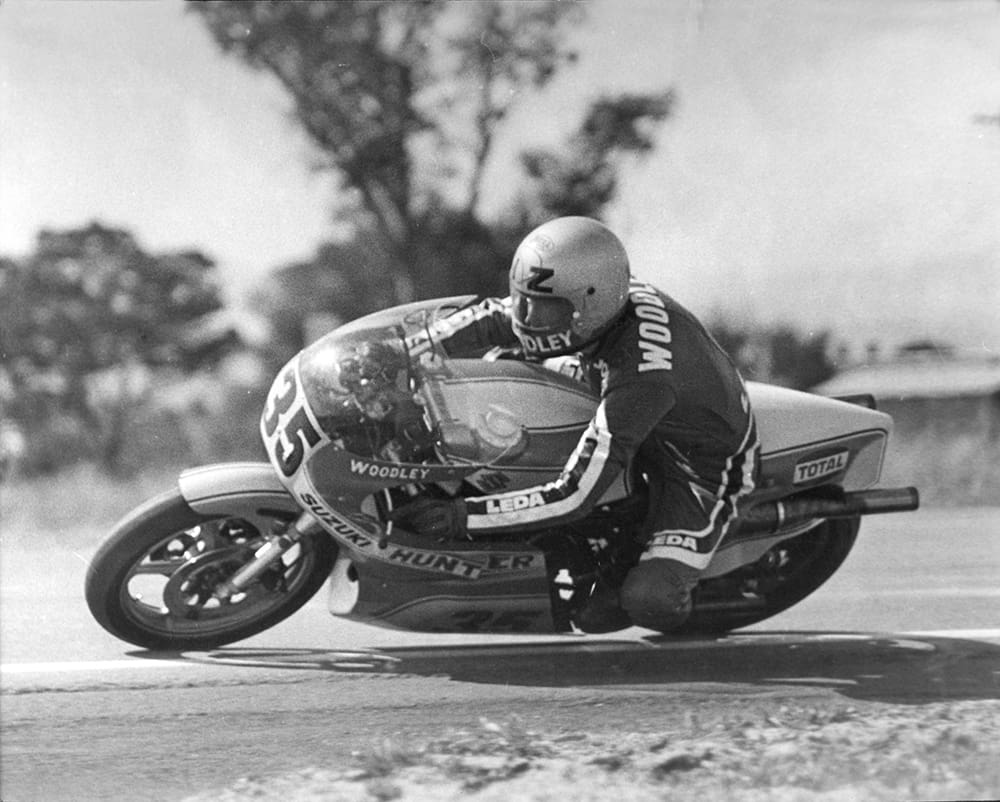

Woodley, with his distinctive helmet, at Bathurst

The Preliminary

Crosby went on to win Saturday’s Unlimited International to set a new lap record with a top speed of 273km/h.

“The KR750 was quite a good jigger to use but it lacked top-end speed,” Crosby said. “It had good mid-range but it was at the end of its life cycle. The KR750 was lightweight, had a reasonably low centre of gravity and it steered and handled. I was feeling quite confident because the bike was good, I didn’t have to change much.”

Croz was followed home by Rob Phillis, 19-year-old Boulden, and an improving Woodley.

Woodley gets his taped-up knee down on the RG500

Race-Day

On Sunday, Woodley handsomely won the 500cc race on his RG500 in front of almost 30,000 weekend fans, while a young TZ350 rider named Wayne Gardner finished in seventh. The race, however, was overshadowed by the crash that tragically took Ron Toombs’ life.

Besides this, Crosby remained confident for the big race: “It was no problem when I had skill, daring, cunning, and all those other things that you need! I was confident with the bike.”

Battle Mountain

Crosby took the holeshot and was leading at the end of the opening lap, the Mountain section still damp for the first few laps. Following Croz were Boulden, Woodley, Phillis, Graeme Muir, Gary Coleman, and Rick Perry with a rebuilt, but ill-handling, KR750. A Yamaha TZ750-mounted Stu Avant was up with the leaders but ended up running off at Murray’s.

Crosby managed to hold on to a huge slide at McPhillamy in the damp, but for him it didn’t register, then Boulden had a full-lock front-end slide before it dried out by lap three. A lap later Woodley slotted his RG into second place, but not for long as Boulden and Crosby banged fairings across the line shortly after. The trio had pulled a 24-second gap by lap seven as the battle of the ANZACs raged on.

Woodley recalls: “Ron and Croz didn’t pull much on me going up the mountain but I was under-geared as the weekend went by, because I got faster and faster. Their bikes were quick down the straight but the RG was the tool for the job.”

Crosby lead over the line for the first four laps, Boulden for the next six and then Crosby for the following four. That didn’t reflect the true situation.

Boulden says: “The race was such that we changed positions every lap, to the extent that coming off the end of Conrod Straight we were hitting fairings – we were that tight! Crosby would try to out-brake me [into Murray’s] because I had the horsepower advantage, but I was still getting used to holding it flat over the last hump!

“The problem is there were three humps and by the end of it the difficulty was getting the front wheel down and getting on the brakes after the last one, because the front comes up and sort of floats for a while. And because we were all going so fast I unofficially did over 300km/h, so unless you got on the brakes hard it was hard to pull up. So you had to make sure the front wheel was right down.

“After the first half dozen laps I knew what I was going to do, so I thought there was no point trying to race him across the top.”

Croz knew how to keep the front wheel down at the third hump. “We were having the same problem. I can remember physically pushing my head right inside the cowling to try to get the centre of gravity as far forward to keep the wheel down. But sometimes you just couldn’t keep it flat, you had to roll off.”

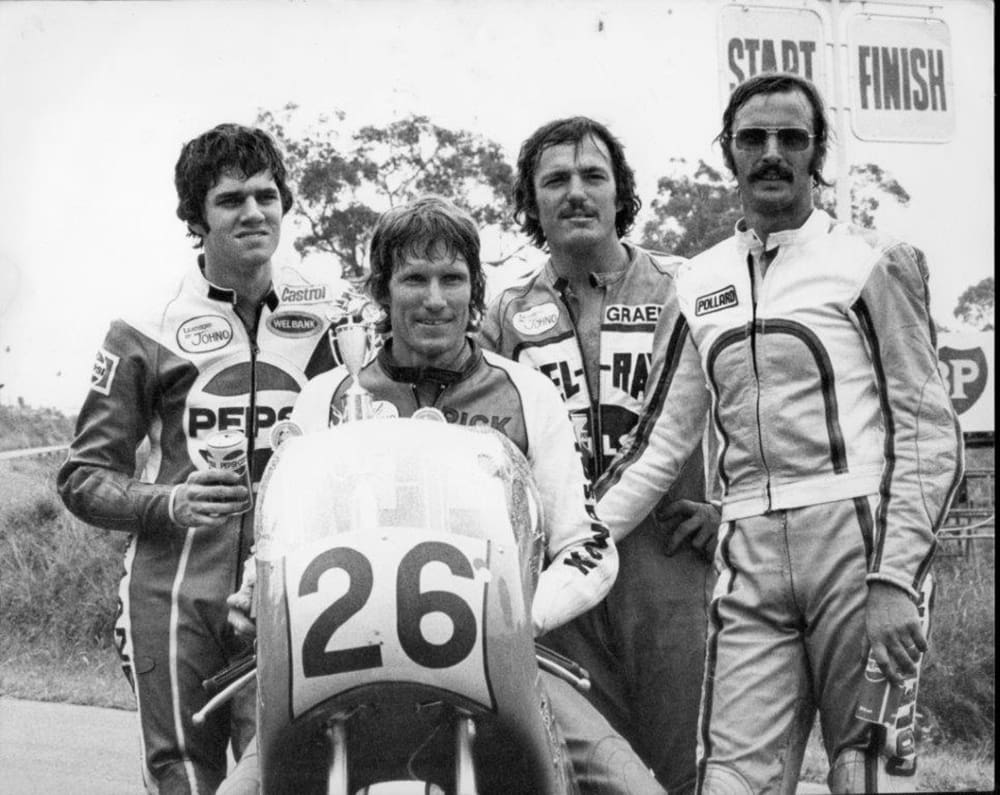

(Left to right) Boulden, Perry, Crosby and Coleman

Then Crosby began foxing the 19-year-old. “They should respect their elders!” he said. “I recall putting all the bloody effort into doing all this (over the mountain) and ending up being passed before Murray’s. I started to be a bit more circumspect as to where I was going to be, I’d like to think it was a game plan, because if I kept doing the same thing for 20 laps, when it came to the last lap he’d know what I’m going to do anyway. So I backed off a little bit.”

The trio would tear along Mountain Straight with Woodley closing the gap before the Cutting. Time and itme again Boulden would fly past the pair on the long run down Conrod Straight. Crosby was passing Boulden under brakes into Murray’s, Hell Corner, into the right hander at the end of Mountain Straight, and then over the mountain.

“After about four laps of doing this I thought it was a waste of time, I may as well just hang in there,” Croz says. “But John Woodley came more into it towards about lap 10. John was passing me over the mountain. I remember him passing me through McPhillamy Park and positioned to go over Skyline.”

Boulden takes up the story: “With Croz on me all the time I had to be weary, so I was backing off a bit at the last hump as I had the power advantage. But he obviously wasn’t, so I’d get to the last hump, roll off a bit to try to get the front down earlier, then Crosby would be back all over me again! Each lap he’d drive up the inside of me and we’d bang fairings, I’d turn to Croz and he would smile at me!

“Then we’d go to the next corner and I had the power advantage and get back in front again. That went on, it seemed like, every lap!”

Woodley adds: “My recollection was at about lap six I realised they weren’t pulling away from me. I thought, ‘man, I can win this’. As the race went on, to win it I had to be in front going onto Conrod and be as far down the straight as possible, so when they overtake me they’ll be approaching Murray’s corner at the bottom so much faster than me, so I should be able to out-brake them.”

Boulden chimes in: “I just knew getting across the top Croz would pass me first, Woodley would then pass me, I’d sit with them down the mountain and I’d pass John first and then get Croz halfway down the straight. That happened lap after lap. I lead, but only over the line, I don’t think I ever lead a full lap.

“I thought as the race went on, ‘this is going to be interesting’ even if I am going to get him on the straight. He’s only got to be half a bike in front of me because the finish line at Bathurst is very close after Conrod.”

Woodley at Murray’s Corner. Racetrack barriers have changed a bit since the 1970s

The Showdown

It all came down to the last lap and there was nothing left on the table. Gentleman John continues: “I led onto Conrod on the last lap. I knew I had to do that if I was to have any chance of winning. I passed Croz at Forrest Elbow, I led onto Conrod on the last lap but at Forrest Elbow the brake lever felt a bit funny, so I thought I might have to do a pump at the end of Conrod, but the brake pads were on the metal even though we’d put a new set in for the warm-up lap!”

Crosby had the hammer down on the last lap and was further along Conrod than he normally was, which hindsight says may have cost him the race. With Boulden now going past him at a much faster speed differential, Croz was unable to tuck into Ron’s slipstream as he went by.

Crosby says: “I put a big effort in and got a bit of a gap coming out of Forrest Elbow, and down the straight the gap was a bit longer. By the time he got to me the passing manoeuvre happened further down the straight. As a consequence his passing speed differential was greater than mine for me to get back into it by the time I got to Murray’s. But I couldn’t do it. He was about a bike length ahead.”

Boulden again: “I passed Croz a bit later down Conrod, when normally I’d pass him about half way. This time it was more like, ‘shit, I’m not going to get to him’, because he put in that hard lap. Obviously he knew exactly what he was doing, he had to get a bigger gap on me.

“It was only the last lap I made the decision to hold it flat over the last hump, which I’d never done, to try to get that little bit extra on Croz, but he still dived under me,” Boulden sais, laughing. “So I only made the decision as I passed him.”

“He obviously had a much bigger go, but I had just enough to get out [of Murray’s] because most times previously we’d go across the finish line and I was only half a wheel in front. And we were actually touching fairings because he wanted the line. I was on the outside and he was on the inside. If I hadn’t backed off until I was airborne prior to the last hump, he would have had a bike length on me and he would have got out of the corner better and I would have lost it. Absolutely!”

Despite Crosby’s brave final burst, Boulden took the $2000 prize from Croz and Woodley. All three received a standing ovation from the crowd, and Woodley set the fastest lap, a 2m15.6s, of the race.

Boulden reflects: “I was quite elated, as you can imagine. John’s bike was underpowered and under geared. He was a more calculating rider on the basis he was very clean and fair, so you could see there was more planning in what Woodley was doing compared to Croz, who would just have a go. Croz would just ride as hard as he needed to, what he’d always done because he’s got plenty of ability.”

Woodley recalls: “The RG500 was fantastic. I wouldn’t say I was being a demon, it’s just that everything came together. That was when I was riding at my absolute peak. I only ever thought I matched Croz once – that race at Bathurst.”

The ecstatic 1979 Bathurst winner: Ron Boulden

Weapon of choice

Suzuki RG500

The 1979 MkIV has the front two cylinders lower than the rear pair, allowing the engine to be lower and further forward in the chassis to keep the front end down. The 54 x 54mm 92Kw (123hp) engine also featured a cassette side-loading transmission for ultra-fast ratio changes. If you didn’t race a TZ750 and weren’t a factory TKA rider, you had one of these

Yamaha TZ750E

Work on the OW19/TZ750A (codename YZ648) prototype began in May 1971. Giacomo Agostini won the Daytona 200 in 1974 on a TZ750, which was followed by massive success around the globe by works teams and privateers for several years. The 67kW (90hp) 694cc TZ700 engine soon became 747cc, with only minor modifications until the final 89kW (119hp) TZ750F model was built in 1979

Kawasaki KR750

On the back of the 1969 H1R and the 74kW (100hp) H2R (1972), Kawasaki developed the water-cooled KR750 triple

to compete with the mighty TZ750s in 1976. The KR750 gained 11kW (15hp) over its air-cooler predecessor to

produce 86kW (115hp) from its 748.2cc engine. Unlike the TZ750, the KR750 was only available to factory riders, but

was outdated by 1979

Words Terry Stevenson

Photography John Woodley, Graeme Crosby, Ron Boulden & Greg McBean