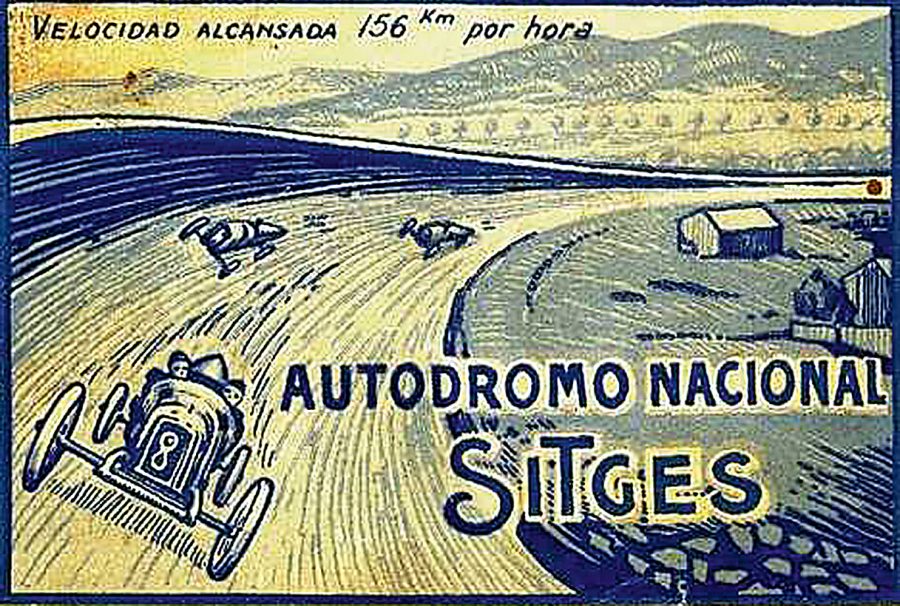

In the farming hills overlooking the popular seaside town of Sitges, with its yacht club and marina full of expensive boats, sits an immense kidney-shaped bowl with banked high-speed corners at each end. Today hemmed in by the motorway to Barcelona and the suburbs of Sitges itself, this long-abandoned structure is the Autodromo Nacional Sitges-Terramar. It was Spain’s first purpose-built circuit and only the second such in Europe, just months behind Monza which opened in 1922.

Both Monza and the Brooklands track in England – the first purpose-built motor racing track in the world, which opened in 1907 – featured huge banked corners. Brooklands used formed concrete while the bankings at Monza were a macadamised surface over a timber substructure. These two tracks also had a network of other roadways so that different variations of circuits could be used. In the case of Sitges-Terramar, the entire track was constructed from concrete.

The sheer size of the place is breathtaking. And when you consider that it was constructed in just 300 days beginning in 1922, at a cost of 4 million Pesatas (approximately $450,000 at the time), the feat becomes even more extraordinary. The two-kilometre banked oval consumed 3500 tonnes of cement in its construction.

It was the brainchild of millionaire civil engineer and amateur racing driver Frick Armangue, who raised the capital to build the track with the aim of it becoming Europe’s motor racing centre. He enlisted architect Jaume Mestres to design the track and engaged a leading construction company to undertake the building work.

Armangue insisted on the top specification for the concrete and the substructure, which included a comprehensive drainage system, all of which added considerably to the cost, but provided a surface that has basically withstood crumbling and cracking for almost a century. In marked contrast to Sitges-Terramar, Brooklands’ concrete surface began sinking and cracking within months of being laid, and required constant and expensive maintenance.

At each end are steep bankings that rise at up to 60 degrees – almost twice as steep as NASCAR ovals, the steepest of which is 36 degrees. It is virtually impossible to scale more than halfway up the bankings on foot, and only centrifugal force keeps vehicles in place on the upper extremes. At one end the circuit is cut into the rock hillside – a massive excavation job – meaning the inside edge of the track is a rugged and unforgiving stone wall. This corner is a parabolic shape, while the opposite banking is entirely above ground and is a perfect half circle. Originally the infield hosted an airstrip, just like the similarly conceived Brooklands, and this saw vigorous use for the inaugural race meeting.

Sitges opened for business on 28 October, 1923 with the ceremony performed by no less a dignitary than the King of Spain, Alfonso XIII. The first Gran Premio d’Espana was open to vehicles with engines of up to two litres capacity, and attracted an entry of just seven cars, but was watched by an enormous crowd. The main grandstand was packed with elegantly dressed ladies and men in suits. The race was won by Frenchman Albert Divo driving a British Sunbeam by just 56 seconds from the flamboyant Count Louis Zborowski in a Miller after two and a half hours’ racing.

The winner averaged an incredible 156km/h, but almost immediately the event was mired in controversy when the organisers admitted they were unable to stump up with the published prize money. The problem was that the circuit’s construction costs had skyrocketed, and unpaid contractors seized the gate takings before the promoter could get his hands on them. Competitors were naturally outraged and tempers flared in the pits after the racing had concluded. As a result, the international motor racing authority slapped a ban on the track until the prize money was paid, which it never was.

In 1925 the circuit was leased from Armangue by the Catalunya Automobile Club which conducted a handful of minor meetings before walking away. In 1930 the entire site was bought by racing driver Edgard de Morawitz, who managed to reopen the circuit after several years’ work. De Morawitz actually conducted the 1932 Spanish Motorcycle Championships at the track with racing held in a clockwise direction, opposite to the cars, but no other major meetings took place under his stewardship.

But with the onset of the Spanish Civil War in 1936, the Autodromo was doomed as Spain embarked on four bitter years of internal conflict and the site began to decay with weeds growing through the joins in the track surface and trees and shrubs encroaching from all directions. The last attempt to use the track in the manner for which it was originally intended was in the early 1950s, for the VI Volta a Catalunya, by which time it was really showing its age and was naturally considered to be highly dangerous, even by the lax standards of the era.

Shortly after the turn of the 21st Century, local developer Marcel Ricart took over and announced plans to reopen the circuit as a sort of motorsport-themed playground called L’autodrom Resort but, despite much publicity and as a result of Spain’s serious economic situation, nothing has happened since, apart from sedate demonstrations by vintage car and motorcycle clubs.

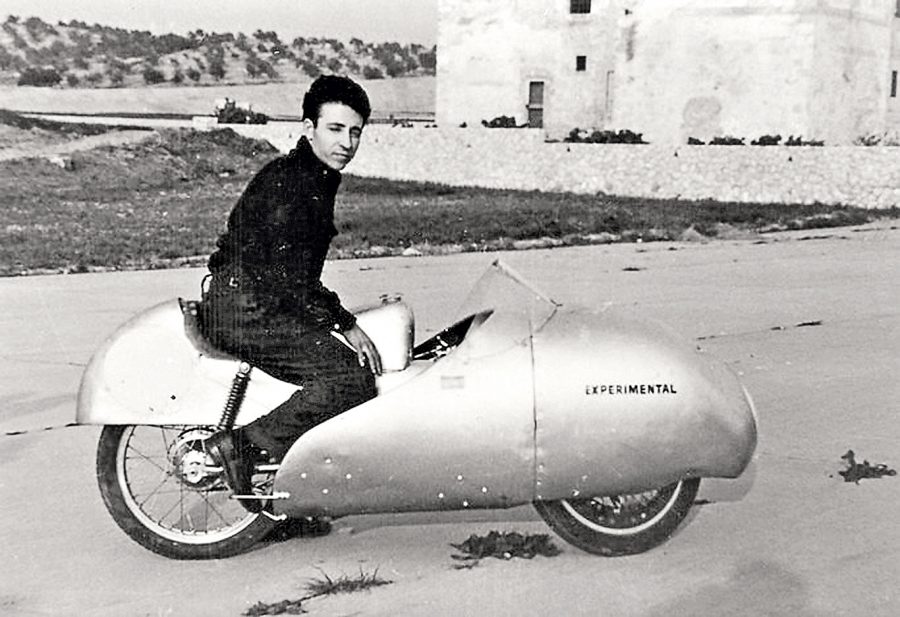

From time to time there has been motorcycle club static displays, including one in 2010 to celebrate the Bultaco marque. This included runs by the fully-streamlined Bultaco record breaker ridden by former Grand Prix competitor Ricardo Quintanilla who was part of the team that established the records in Monlhéry, France in 1960.

In 2012, after considerable agitation by energy-drink giant Red Bull, the circuit was cleared of weeds and debris to allow Spanish Rally hero Carlos Sainz to drive an Audi R8 LMS GT3 for several laps. Sainz eclipsed the original lap record set in 1923, but not by much, which is quite remarkable considering he was aboard a state-of-the-art $350,000 5.2 litre V10 racer pumping out 500 horsepower.

In the 1923 Grand prix, Count Zborowski established the lap record at 45.8 seconds, a time which Sainz was only able to prune to 42.6. Both Sainz and Touring Car star Migeul Molina (who was unable to match the lap record) were critical of the change of elevation where the bankings merged into the flat sections, saying it was extremely dangerous. Both drivers came away with a new admiration for the courage and skill of the competitors who plied the same track almost a century before.

The same year a well-attended retrospective event was held at the circuit, again raising hopes that a resurrection was nigh, but for now, the infield hosts a chicken farm, with sheep and goats grazing among the scrub. Much of the grandstand is still in place opposite the start/finish area, although the front section facing what was the start/finish line has been enclosed, and some of the pit buildings still stand – indeed, what were once race garages now hold dusty farm machinery.

In the middle of the back straight, which is actually curved, stands what was a control tower and which is in remarkably good condition. Today, the huge kidney-shaped bowl lies silent, overgrown with weeds, but considering it is over 95 years since it was built, the track is still in remarkably good shape. To discourage any illegal activity, furrows have been cut into the main straight and rather flimsy barriers erected, but it is still possible to ride around sections of the circuit under strict supervision, although casual intruders often encounter the local leasehold farmer who vigorously defends his property. There are however, opportunities to view and walk sections of the circuit from various points providing you keep a low profile.

Unloved and largely forgotten it may be, but the Autodromo Nacional Sitges-Terramar still exudes the mysterious charm that seems to accompany abandoned sporting arenas – a stark reminder of a grand plan that never quite came off.

Where is it, exactly?

The old circuit is situated close to the C-32 toll road from Barcelona in the north and Valencia in the south, high up in the hills that overlook Sitges and the blue waters of the Mediterranean Sea. Sitges itself is today is more famous for its gay community and annual Gay Pride festival than for its former role as a fishing port, or its would-be mecca of motorsport.

A small village near the town of Sant Pere de Ribes nestles right beside the circuit, separated from the towering old bankings by a stream. Approaching the village, the eastern banking of the track, with its near-vertical top section, pokes eerily out of the trees and is clearly visible from the main road. A tunnel runs under the first section of the eastern banking – what was once an access point for spectators to enter the infield area is now overgrown covered in graffiti.

Words Peter Turner Photography Ramon Tomas