There is one big thing that separates Fabio Quartararo from MotoGP’s other recent rookie revelations Marc Marquez, Maverick Viñales, Johann Zarco and Alex Rins. Those four all arrived in the premier class riding an impressive upward curve: winning in 125s or Moto3, then winning in Moto2.

Quartararo did not. When the French kid was a little tacker, he won everything he entered between the ages of nine and 12. At 14 he became the youngest rider to win the Spanish CEV Moto3 championship and the following year, he defended it in an utterly dominant season. MotoGP talent spotters called him the next Marquez. Even MotoGP was convinced, so much so that Dorna, the FIM, IRTA and the MSMA changed the rules specifically to allow Quartararo to contest the 2015 Moto3 world championship before he had reached the minimum age.

Some paddock people even predicted he would win the title at his first attempt, which no one ever said of Marquez, Viñales, Zarco or Rins.

Quartararo made his Grand Prix debut in Qatar in March 2015 and gradually sunk, almost without trace. He finished his rookie season in 10th overall, lost his ride, got a ride with another team for 2016 and ended up three places lower, in 13th. In 2017 he moved to Moto2, hoping to bring his career back to life. It didn’t work. He completed his first Moto2 campaign down in 13th place and changed teams once again.

After the first six races of 2018, he was running a lowly 12th overall in the title chase. Then he arrived at Barcelona-Catalunya for what would be his 56th grand prix start. His Speed Up team made some set-up tweaks that worked, and Quartararo ran away with the race and crossed the line to celebrate his maiden grand prix victory. Suddenly his phone started ringing again.

You see, by 20 years of age he’d already had a rollercoaster of a career and he believes the bad times are helping him to have better times.

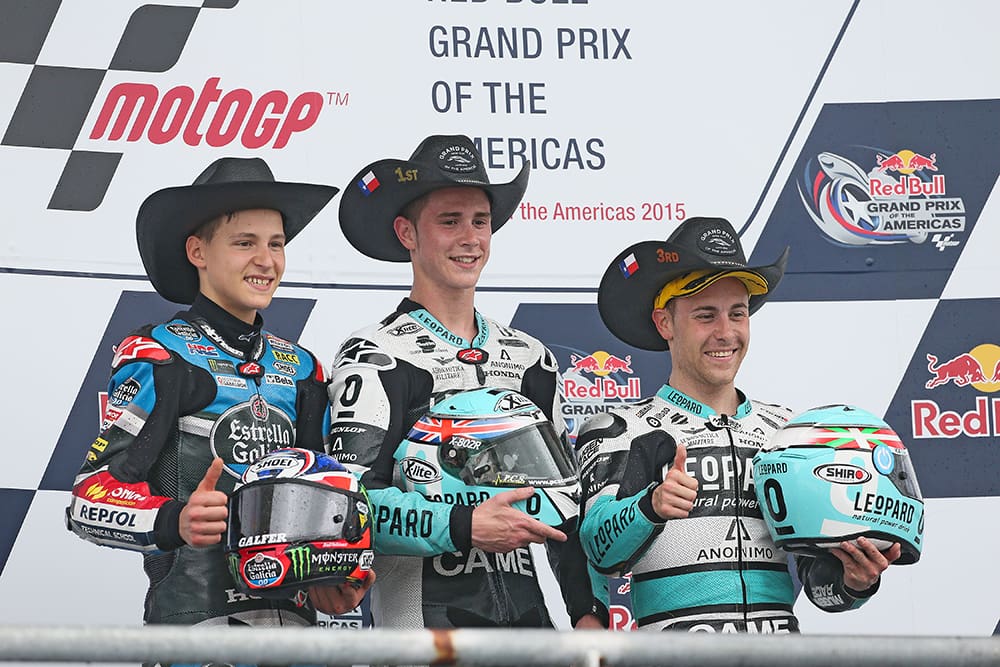

“When people compared me to Marquez, I was only 16,” he says. “I think the pressure got too much, it was too stressful. Then I broke an ankle [in September 2016] and missed six races, then the next year I was with the Leopard team and had a really tough season.

“Those tough years gave me a lot of experience – they were really bad for results, but so good for my experience. Every good moment I had when I was at Leopard was a big success, because 95 percent of that time was negative. This has taught me that you can also learn from negative moments and take small positives from them.”

Very few people predicted Quartararo would be the stand-out rookie of 2019. Most expected 2018 Moto2 world champ Pecco Bagnaia, 2017 Moto3 world champ Joan Mir or 12-times GP winner Miguel Oliveira to lead the rookie charge.

But, despite his last-minute call-up, Quartararo was on it from the get-go: he set the fastest lap in the season-opening Qatar GP, then qualified on pole at Jerez (taking the youngest-ever pole record from Marquez).

Quartararo does have advantages over the other rookies. He rides a Yamaha YZR-M1, the most rider-friendly bike on the grid, and he rides for the new Petronas SRT squad, managed by former GP winner Wilco Zeelenberg, who knows how to look after a rider.

“Wilco is really good, because I’ve had some bad experiences with team people who really push you for results. This kind of thing makes me stressed and then I don’t ride smoothly. Now the whole team works hard during the weekend and when we get to the race they say, do your best. When people don’t put pressure on me I can go much, much faster.”

Marquez has already opined that life can be easier for a rookie, because if you have the right people behind you there’s less pressure, so a podium is a great day and you can worry about winning later. But later on, winning is all that counts. It remains to be seen how Quartararo reacts in those conditions, but meanwhile he’s loving every minute: fist-bumping his crew every time he walks into the pits and grinning a toothy smile from ear to ear every time he gets off the bike.

One thing stands out when talking with Quartararo – he is fiercely intelligent, like Marquez and Valentino Rossi. And these days, this is what makes the difference at the very top.

“On a MotoGP bike you need to think more than when you’re riding a Moto2 bike. In Moto2, you create a good bike set-up and you do the full race at full gas, trying to control the tyres.

“In MotoGP you need to control the tyres, you need to think about the fuel tank, when it’s full and when it’s nearly empty, you need to think about the three power maps, and you need to think about the three engine-braking maps. So you need to think a lot when you’re on the bike and I think this helps me stay calm when I’m in the box.

“For me, it’s good to think. Of course, you mustn’t think too much. You must focus on your riding, but as soon as you feel you should change the power map or engine-braking map you must change them.”

Quartararo believes his biggest strength as a rider is his smoothness, which suits the M1.

“The Yamaha is the bike that needs to be ridden really smoothly. I remember Jorge Lorenzo rode the Yamaha really smoothly and that’s why he won a lot of races.”

He is also very good at saving front-end slides, which is one of the keys to Marquez’s domination.

“It’s difficult to manage because you lose the front in less than a tenth of a second, so you really need to be very focused on what you’re doing. If you don’t have that feeling with the front of the bike, it’s easy to crash because the front goes really fast.”

If Quartararo’s transformation from zero to hero is the stuff of fairy-tales, it’s got not nothing on the change in his relationship with Rossi.

“Ten years ago I was waiting for Valentino outside his hospitality to have my photograph taken with him. And now he looks at my data to see how I’m doing my lap times. For me, this is quite strange… No, it’s really strange!”

Of course, Quartararo also examines Rossi’s data, looking to learn from the old master.

Quartararo, Catalunya MotoGP 2019

“I need to improve the way I go into the corners, the way I manage the gas and the way I manage wheelies. I still have many things to learn. For example when I see Valentino’s and Maverick’s data, I can see the experience they have in controlling the throttle, so I still have to learn these things from them.”

“I try to control wheelspin more by myself [without traction control] because I think this is the best way to work. At the start of the year I was happy to exit corners at full gas, but for sure if you only use 80 percent gas you will exit the corner faster because instead of spinning the tyre you are building speed. When you spin at full gas you burn the tyre and you don’t go forward.”

Born in the French mediterranean city of Nice, Quartararo started learning his skills at the age of four, when his father Etienne bought him a Yamaha PW50. His dad – a former French champion – was so convinced of his son’s talent that they moved to Spain, the cauldron of global bike racing. When Quartararo was nine he won the Catalan 50cc championship, then the Catalan 70cc title, the Catalan 80cc crown and the Mediterranean pre-Moto3 series, which got a ride in the CEV Moto3 championship.

He now lives in Andorra – a tax haven between Spain and France where many MotoGP riders set up home – and he trains mostly in Spain.

“I sometimes ride RMU MiniGP bikes [also used by the VR46 Academy], but I do more motocross than anything. I train a lot in Spain with Jack [Miller] and John [McPhee]. It’s good experience to have several top riders fighting on the same bikes.”

Inevitably, Quartararo’s instant speed in MotoGP has made his manager Eric Mahé a busy man. Mahé has managed Quartararo since he moved to Moto2, trying to find his way in a paddock where the action can be just as rough as it is on the racetrack.

“In this world there are a lot of snakes, a lot of bandits,” says Mahé. “I chose Speed Up for Fabio in 2018 because they are like a family team. Apart from them, there were four other teams interested in Fabio. When I entered the office of one of the teams, the first question they asked me was this: ‘Eric, how much money do you want to improve our chances of signing Fabio?’ They wanted to give me an envelope full of money! Crazy! Terrible!

“At this stage, I’m a bit like Fabio’s uncle. There is an affection which is important for his confidence, because if you cannot trust the guy who’s managing your money, then forget it…”

Right now, Quartararo has everything going for him. Is he the man to take Marquez’s crown?