The groundbreaking Suzuki GSX-R750 was the world’s first superbike. So we took Mick Grant’s racing version for a blast – 30 years after it won the British Superstock title

TEST Alan Cathcart PHOTOGRAPHY Jay Groat

It’s hard to think of any new model as immediately dominant straight out of the box as the Suzuki GSX-R750 was in its debut 1985 season. Nothing demonstrated this better than its supremacy in that year’s inaugural MCN British Superstock Championship, where the new GSX-R750 dominated the first-ever series run anywhere in the world to carry the Superstock name, winning nine of the 11 races.

Veteran star Mick Grant, then 41, won the first four rounds in succession, proving he didn’t need to apply for the pension book just yet by convincingly wrapping up the title with five victories in the end, on the bike entered by UK importers Heron Suzuki. Each of the races in the series offered nail-bitingly close racing between top riders on evenly-matched machinery, which the average spectator could readily identify with – the whole rationale of the Superstock category, and today’s Superbikes.

“It was a lovely thing to ride and extremely reliable – built like a Swiss watch,” Mick Grant says.

“I also won the Isle of Man Production TT on a bog-stock version.”

The Suzuki is history on wheels – and I was twice able to sample it from the hot seat, 30 years apart. The first time was straight after Mick clinched the championship in 1985. I made my re-acquaintance with the legendary bike three decades on at the South African TT Revival series.

Clambering aboard the GSX-R delivered a real surprise. I’d forgotten how low the seat was, especially compared to later 750 Superbikes. The riding position is rather cramped. You’re effectively wedged in place, and it takes some manoeuvring to hang off the side in turns. No wonder it was such a fantastic bike for endurance racing.

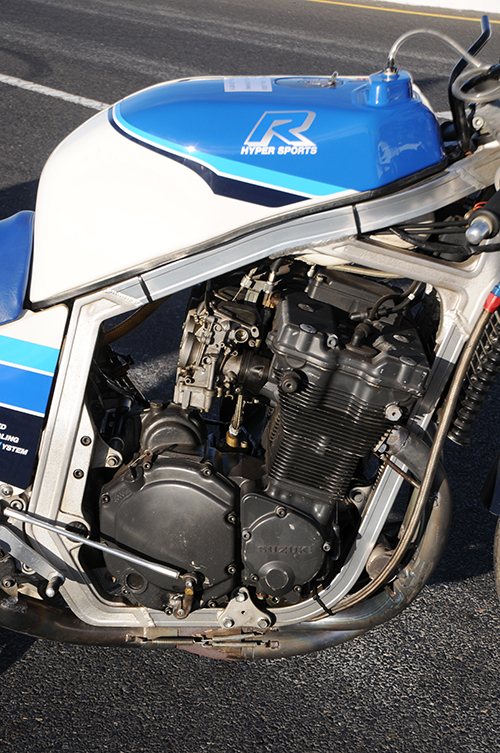

The stock flat-slide Mikuni carbs have a very stiff throttle action due to the heavier return springs fitted to counter the suction effect – which apparently led to them occasionally sticking open

in Mick’s hands.

Coupled with the sudden pick-up of the flat slides compared to a conventional CV carb, it’s very easy to spin the back wheel until the triple-compound Michelin has warmed up, and you must learn how to preload the throttle slightly exiting a turn before cracking it wide open for maximum drive.

Accelerating down to the first left-hander brought the next surprise – the brakes didn’t work! To be fair, I was warned about this: so I was ready for having to squeeze very hard to make them work – albeit not well – when cold. I held the lever on lightly as I completed the first lap, after which they worked well enough to stop the Suzuki at the end of the 800 metre-long back straight. But even after they’d warmed up they seemed rather wooden – something I also complained of back in my 1985 test of the bike, so this wasn’t a case of modern expectations of 30 year-old hardware.

The Suzuki just didn’t stop as well as I’d expected with those 10mm bigger Brembo discs than standard, and it also required a pretty high lever effort. Thinking back, I remember this was an issue when Brembo swapped – not long before the Suzuki raced – from cast iron to stainless steel material for their discs, so maybe that was the reason. At least the Superstock GSX-R stayed on line and didn’t sit up under braking when cranked over, as I remembered from my Snetterton test its unruly-handling race-framed TT1 counterpart had done.

The GSX-R Superstock engine has a high idle speed of 2500rpm, a favourite trick of Suzuki in particular back then in those pre-slipper clutch days, aimed at preventing engine braking upsetting the handling. That’s why Frankie Chili’s factory-backed Alstare Corona GSX-R750 Superbike had the same high idle 15 years ago. This meant I didn’t have to worry about chattering the rear wheel anchoring up from high speed for Killarney circuit’s second-gear hairpins. First gear on the Gixxer is just for getting off the line – and it also helps overcome that fierce pick up from a closed throttle via the combo of the flat slide carbs and heavy throttle springs.

Three decades on, the great-sounding Superstock engine is still a lovely engine to ride, pulling smoothly from low down with no flat spot caused by the Yoshimura race pipe lifted off a factory-built TT1 racer. The untuned engine has good midrange torque, although the effect of the open pipe and carburation changes has made the power delivery quite a bit peakier. There’s usable poke from 5000rpm onwards. But the real kick doesn’t come until 7000 revs, giving a relatively narrow usable powerband for a four-stroke 750cc roadster, before the 10,500rpm rev-limiter kicks in on the stock igniter box that’s currently fitted – instead of the higher-revving ringer used by Grant.

But the ratios on the standard six-speed gearbox are so well matched it’s easy to keep the engine driving, though I found it difficult to change up smoothly every time without using the clutch. Although the race-pattern right-foot gearchange felt reasonably precise and clean, there’s a fair bit of crankshaft inertia in spite of the much lighter crank than the old air-cooled GSX750. So fanning the clutch lever to get smoother upward changes doesn’t result in any dramatic loss of revs.

When it was first launched the GSX-R750 acquired a reputation as a rewarding but demanding streetbike. What the French call a nervous motorcycle would occasionally flap the front end unpredictably, or at worst, if badly set up, deliver twitchy, skittish handling and, on certain tyres, an insidious high-speed weave. We’ve since come to take some of this for granted as the entry ticket to race-quality handling, where if you get it wrong you must work at dialling out your set up mistakes. But back then when men were men bikes were expected to be solid and planted in their steering. If you didn’t have to raise a sweat slinging it from side-to-side through a series of turns, then it was nervous.

The Suzuki was the gateway to the modern world, and the combination of its lightweight chassis and the racing suspension on the Superstocker results in a surprisingly modern-seeming bike you can chuck around and enjoy, rather than have to tame.

Although Mick Grant recalls it did occasionally set up a high-speed weave on him, I’m glad to say that never happened to me either at Snetterton 30 years ago or Cape Town today, and though I was rather cautious with it to begin with after the tales I’d heard of sudden misbehaviour, I soon realised this is a nearly vice-free bike. The steering is neutral, there’s no sign of tuck-in when leaned hard over, even on the brakes, and the suspension coped ideally with the many bumps on the Killarney circuit, where other more recent bikes got badly unsettled, especially with the power on.

The front end tended to wash out a bit around the fast left-hand sweeper on to the Killarney main straight, but that’s where a bit of muscle came in useful to pull it back on line, and I was impressed how well it rode the seaside circuit’s lumpy surface, especially leaned over in a fast turn where the low centre of gravity with rider installed would have been a positive factor.

It leapt around a little at speed down the long main straight, but the front wheel didn’t flap and it stayed going where it was pointed. Not bad for 30 year old suspension at something approaching 240km/h.

The Honda Fireblade is always quoted as the first sportsbike of the modern era – but eight years before it appeared, Suzuki got there first with the GSX-R750, beating Honda to the punch by creating a 750 with the performance of a 1000, but the handling of a 600.

In the context of the mid-1980s this was a truly revolutionary motorcycle. The fact it’s worn so well 30 years on down the line that Mick Grant’s title-winning Superstock version is still such a satisfying bike to ride, is a due mark of its significance.

The winds of change

First superbike of the modern era

Suzuki called what was effectively an oil-assisted air-cooled format the Suzuki Advanced Cooling System (SACS). This feature was the single greatest step forward in meeting the company’s ambitious design targets of reducing the weights of individual components in the new engine versus the old.

The 70 x 48.7mm short-stroke 749cc engine weighing just 73kg (compared to the 80kg 747cc GSX750’s 67 x 53 mm format) had four valves per cylinder operated by twin overhead camshafts with central chain cam drive.

It was an evolved version of the Twin Swirl Combustion Chamber (TSCC) format first seen in 1980 on the GS1000, which took advantage of the turbulence caused by the incoming fuel charge to increase airflow and enhance flame passage, en route to a claimed output of 77kW (104.5hp) at 10,500rpm.

The 26mm intake and 24mm exhaust valves sat at 21° and were fed by Mikuni VM29SS flat slide carbs breathing from a large eight-litre airbox located under the fuel tank. A six-speed gearbox was matched to a hydraulic clutch, rather than the then-commonplace five-speed transmission with cable clutch.

And rather than hanging the generator on the end of the crank as was hitherto commonplace, so reducing ground clearance and lean angle, Suzuki relocated it behind the cylinder block above the gearbox, driving it via a spur gear. Reducing the width of the engine in this way allowed a potential 55° banking angle, far more than the competition.

This entire layout was revolutionary in its format – many of the Gixxer’s design components which we now take for granted in performance engineering were pioneered on this bike.

Light is fast

First of the featherweights

Ever since Honda created the four-cylinder Universal Japanese Motorcycle (UJM) back in 1969 with the CB750, it’s taken turns with its three Japanese rivals to re-invent the concept. For the 903cc Kawasaki Z1, the original 893cc Honda Fireblade, and the first one-litre Yamaha R1 each took it in turns to fundamentally change the spirit as well as the science of sportsbikes for ever with their arrival.

Thereafter, all other manufacturers would have to re-evaluate their design strategies – and we, the bike-buying public, benefited enormously. But no other motorcycle has taken such a huge step forwards, and in so radical a manner, as the Suzuki GSX-R750 which debuted exactly 30 years ago this year.

Compared to its air-cooled, steel-framed, neo-vintage predecessors and those from all other companies, the oil-cooled 16-valve Gixxer with its GP-derived square-section tubular aluminium chassis, Full-Floater monoshock suspension, and then-improbable power-to-weight ratio, was not only the first superbike of the modern era, it also beat the same minimalist path in concept and execution that Tadao Baba would follow eight years later in creating the first Honda Fireblade.

Unjustly, GSX-R750 project leader Etsuo Yokouchi has never been accorded the same reverential status as Baba-san for having thought outside the envelope in creating the bike that put Suzuki on the map as makers of supreme sportsbikes. As demonstrated by its racetrack dominance and showroom supremacy in the wake of the GSX-R750’s appearance, just as the default capacity for such bikes was downsizing to 750cc.