Almost three decades ago, double world champ Troy Corser tried his hand at road racing on a Suzuki RGV250 production machine. This is that bike

His story has taught us many lessons. Our scientists are able to explain away just about every event that has ever happened. Two planets colliding creating life, hydrogen combining with oxygen creating water, and so on.

Now and then, though, something special can happen, inexplicable paths cross, relationships are formed, and miracles are achieved.

In 1990 one such combination of man and machine sparked a chain reaction that would prosper for more than two decades, and result in a young Troy Corser becoming a man, achieving two World Superbike Championships and enough pole positions through his career to earn him the nickname Mr Superpole.

Corser spent his youth racing the off-road scene before turning his attention to the road in 1989. He competed in a couple of local events at Oran Park and acquired the taste for tarmac. A gentle shove from 1987 World Motorcycle Champion Wayne Gardner helped persuade the Corser family that Troy should make the switch and have a crack at the big time.

In 1990 Troy’s grandfather, Ron, loaned him enough money to buy a new 1990 Suzuki RGV250L from Phil Morris Motorcycles and he campaigned it in the AMCN 250 Production Challenge in typical Corser style, winning the series.

The RGV was sold on and sat in a shed forgotten until fellow competitor and two-stroke nut Ken Watson found it and snapped it up. Watson, the current owner, left the bike completely original down to the last nut and bolt. Troy’s bike has never been apart, so it’s a genuine original survivor, which makes getting the chance to ride this piece of Australian motorcycle history something very special indeed.

The 249cc V-twin had spritely performance, with almost 60hp, and the tri-spoke alloy wheels were 17-inch up front and 18-inch rear, making today’s tyre choice not as easy as it once was.

The twin 296mm discs worked well, helped by the fact that, at a claimed 138kg dry, the RGV is quite light. And after throwing the bike around I’m not going to dispute that claim, because it felt like I could turn it inside out if I’d wanted to.

Perfect conditions met us at Wakefield Park near Goulburn. I have to say the dry conditions took a lot of weight off my mind because riding such an important piece of Australian motorcycle history was something that I wasn’t taking lightly.

This bike is not a scrubbed-up, painted and polished museum piece, but exactly as it was when Troy parked it at the end of 1990.

It had been ridden in anger only a handful of times since its heyday, when Ken and his son, Keo, teamed up in an endurance race at Wakefield Park. It got dropped that day, with minimal damage, so the last thing I wanted to do was finish off the job.

This bike is all business to look at and, although it’s clean, it has lost its brand-new sparkle. The paint was just as it was back in the day, and it even wore Troy’s old race number, 47.

I let Ken go through all the pre-ride checks, such as checking the two-stroke oil level, tyre pressures, fuel level and so on – I just stood back and watched an expert at work.

When it came time to fire it up, Ken used a strange method. He didn’t kick it like I remembered should have been the correct style, he didn’t roll start it, and there’s no electric start; he simply leant over and grabbed the kick-start lever with his hand and gave it a prod. It burst into life and Ken went on to warm it up, giving it a bit of a rev every now and then to clear it out.

Burbling away, it sounded pretty smooth and docile, giving me the impression of a pretty straight-forward ride. Oh my god, was I wrong!

There’s nothing straightforward about riding an RGV. As I headed out of the pits with about four grand on the tacho, I thought there was a major issue; the fuel wasn’t on, or the thing had seized – it was gutless and I was running the scenarios through my head. I was trying to figure out what I was going to tell Ken, when all of a sudden it took off like a thing possessed!

As soon as you hit about eight or nine grand, things started to happen in a hurry.

I was clicking through the gears, almost feeding them to the rev-hungry motor, keeping it on the boil. The way you have to keep dancing on the slick six-speed ’box is almost like feeding coal to a steam train.

The power band was so narrow, and unlike a modern Yamaha R3 Cup bike or any other 4-stroke 300cc Supersport machines; no smooth delivery, but rather gasps of power all the way up to 11,000rpm. One minute it’s all happening, but let the revs drop and it’s not.

The handling is quite good in some ways, and in others it takes a lot of getting used to.

It’s pretty easy to get the thing pointed where you want because it is certainly a sweet little chassis in terms of geometry, and it copes easily with the power. It’s probably slightly over-stiff for a bike like this, but beam frames were still in their infancy back in the ’90s.

The suspension is another story. The first thing a modern racer does when they buy a bike, is junk the shock and put an aftermarket one in. And the same with the fork internals. But in Proddie racing back in the day, you had to use the standard original items. There was talk of guys cheating by modifying their standard shocks and forks internally, but the way Troy’s bike felt I think he spent the money on beer.

To be fair, the rear wasn’t too bad keeping things relatively under control, but the grip soon disappeared on full lean angle with that skinny 18-inch rear tyre. The front gave me no feel whatsoever, and I just felt like I was guessing where the limit was every time I tipped in and loaded it up. I’m sure that if I had more time I would have found the limits, but they weren’t right in your face like with a more modern machine.

It gave me a feeling that all was going to be well – until I crashed. If I did crash, though, I was going to lose the front, and that got me thinking about just how far we have come since 1990.

Although the RGV is faster than the modern 300cc four-stroke machines that have taken its place, the manufacturers have made everything much more user-friendly and docile.

Coming in to the pits after my run, I wasn’t sure if I wanted to head back out to try and tame the beast or not. But when I stepped off, I found myself wanting another go – it was Catch 22. I wanted to tame it, but the risks of going again and crashing were high and for those reasons I declined. I reckon Suzuki made a fortune on spare parts during that two-stroke racing era.

RGV250s were unbelievably fast in their day, lapping two seconds a lap quicker than the modern four-stroke 300cc equivalents. That gives you an idea of the capabilities of one of these bikes ridden properly, and fair reasoning as to why they are no longer LAMS-approved.

It was a step back in time riding the RGV, and this bike really did give me a greater understanding of Corser’s capabilities.

It certainly wasn’t the best bike, but he had bravery and a certain touch that the rest of us can only envy.

One-on-one Ken Watson

Ken Watson has been one of the most competitive racers on the national scene for three decades, competing and winning in every class he has put his hand to. Turns out Ken is a bit of a nut when it comes to RGVs, having collected almost enough to run his own race series.

How did you manage to find such a piece of history?

I knew the lad that bought it, Jason Curtis, who rode it at C-grade and D-grade level a couple of times and then parked it up. He lived just around the corner from my place, so in about 2000 I approached him and did a deal.

Didn’t Jason change it at all?

No, he didn’t. It was exactly as it was. It even had a set of Troy’s K591 Dunlops fitted, which I took off and put on my son’s bike.

You have a passion for these RGVs?

Well, you know, I’ve got 11 now and I know them inside out. Keo [Ken’s son] and I race a couple of later models, and we once raced Troy’s in a one-hour race at Wakefield, where we got the lap record.

How long has Troy known that you have the bike?

Eighteen years. He knew from the day I bought it, and we have been bantering about it ever since. I tell him that I’m keeping it because I park it behind my bike in the shed – it’s the only way I’m ever going to be in front of him.

Would you let Troy ride it again?

He is welcome to ride it whenever he wants. I would be really interested to see what he thinks considering it’s so original, even down to the slipping clutch bit.

The other Troy

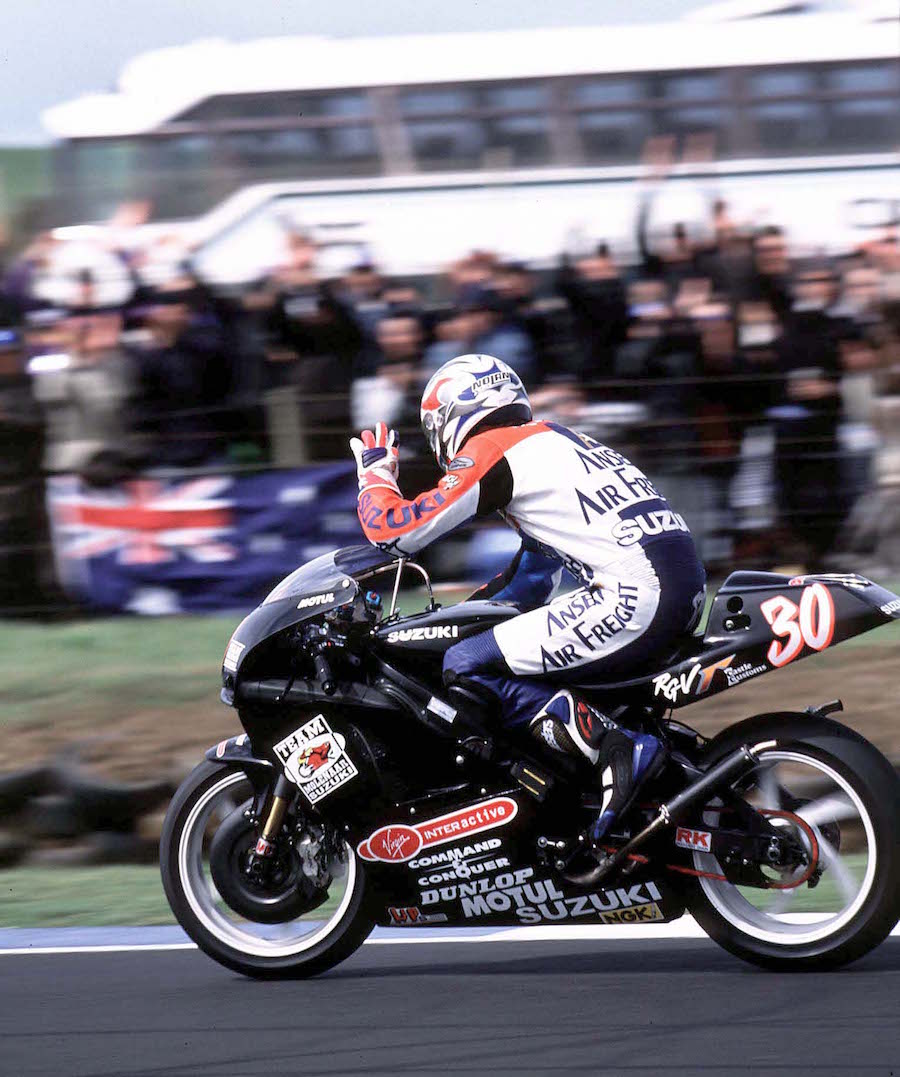

In 1997 another Troy, a young hard-charger from Taree, was making a name for himself in the Australian Superbike Championship riding a Suzuki GSX-R750. And Troy Bayliss was a man on a mission.

Just before the 1997 Australian Grand Prix, long-time member of the GP paddock Gary Flood received a call from Suzuki Japan looking for a potential replacement for injured regular rider Nori Numata.

Bayliss’s name had been put forward and, at 28 years old, he was given the chance to race the Suzuki RGV250 grand prix bike.

Troy’s career started off in the Production class, where he successfully campaigned a Kawasaki KR1-S, so he had an idea what these two-stroke 250s were all about.

Suzuki’s expectations for Phillip Island that year were to roll around and keep it upright, but that’s not Troy’s style. Even though the RGV GP machine had never amounted to much, and had never looked like getting on the podium, Bayliss rode the wheels off the only Suzuki in the 21-rider field and finished sixth, less than 30 seconds behind eventual winner Ralf Waldmann.

Suzuki continued with its 250cc GP project with Numata and a young kid named Yukio Kagayama, but the shine of the 1997 Australian GP with Bayliss on board was about as bright as the light got.

By 1999 Suzuki had abandoned the project to focus on the 500cc category, which turned out to be a good choice because Kenny Roberts Jr won the 2000 World 500cc title.

Bayliss Australian GP 1997

Words Steve Martin

Photography Keith Muir