Words HAMISH COOPER Photography PHIL AYNSLEY

The 1970s and 1980s were a period of great motorcycle innovation, often showcased in Grand Prix and endurance racing. It was a time when conventional chassis technology was becoming overwhelmed by ever more powerful engines from Japanese manufacturers. This inspired free-thinkers to revisit frame and suspension design and several futuristic theories became reality.

One of the most radical was Frenchman Claude Fior’s ‘wishbone’ front fork designed and tested for the first time in 1979. This design would eventually be adapted by BMW into its Duolever suspension, first revealed in the 1993 R 1100 RS, and then on other models.

Fior’s theories on chassis design were no less radical, as he sought to increase frame rigidity and decrease weight. His amazing efforts in racing culminated with rider Marco Gentile tying with Cagiva’s Randy Mamola in the 1989 Grand Prix 500cc title chase.

This journey to the heights of GP racing started back in endurance racing in the late 1970s.

Let’s look at the two motorcycles that bookend his career and the one that put him on the path to scoring points in the Grand Prix 500cc class.

Fior’s fantastic first-born

Obsessed with mechanical engineering as a child, Fior became a teenage mechanic-fabricator in F3 car racing. In 1976, aged just 21 years, he opened a fabrication workshop in his home town of Nogaro, in South-West France, near Turn Nine of the local circuit.

Aimed at the wealthy race car industry, the business also provided Fior with the finances to pursue his real passion: motorcycle racing. Since 1973 he had raced self-prepared motorcycles, eventually taking on world endurance championship events.

These longer, well publicised and factory-backed series were a hotbed of innovation and alternative engineering. Just one clean-sheet design was Laverda’s V6. Meanwhile French company Godier-Genoud’s Kawasaki creations were dragging the Japanese factories to a new level of performance and style. And petroleum giant Elf was just starting to finance the French innovation that would eventually become the Elf-Honda endurance/GP race project of Andre de Cortanze, with hub centre-steering.

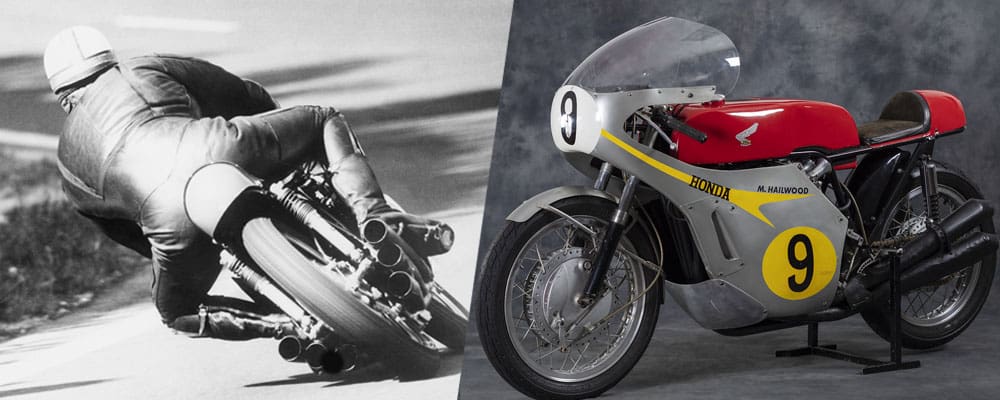

While all this was happening Fior was quietly achieving success that would encourage him to take his own huge leap forward. In 1978 Fior with co-rider and friend Pierre Guy came second in the Silhouette class of the Le Mans 24-hour classic on a standard-frame Yamaha XS1100 converted from shaft to chain drive. Not impressed with the big Yamaha’s handling, he turned up at the next year’s event with his Fior-Yamaha special.

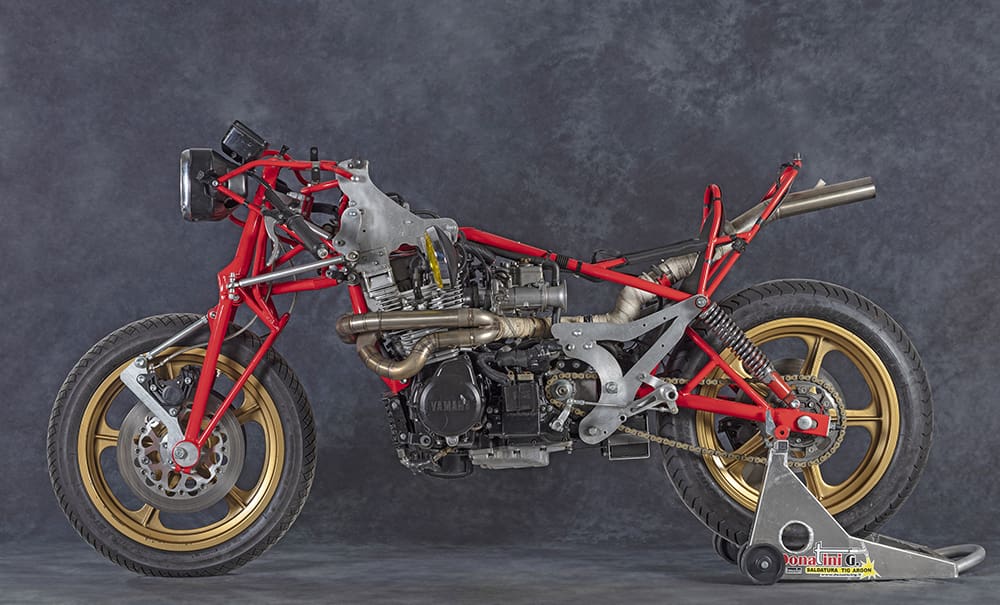

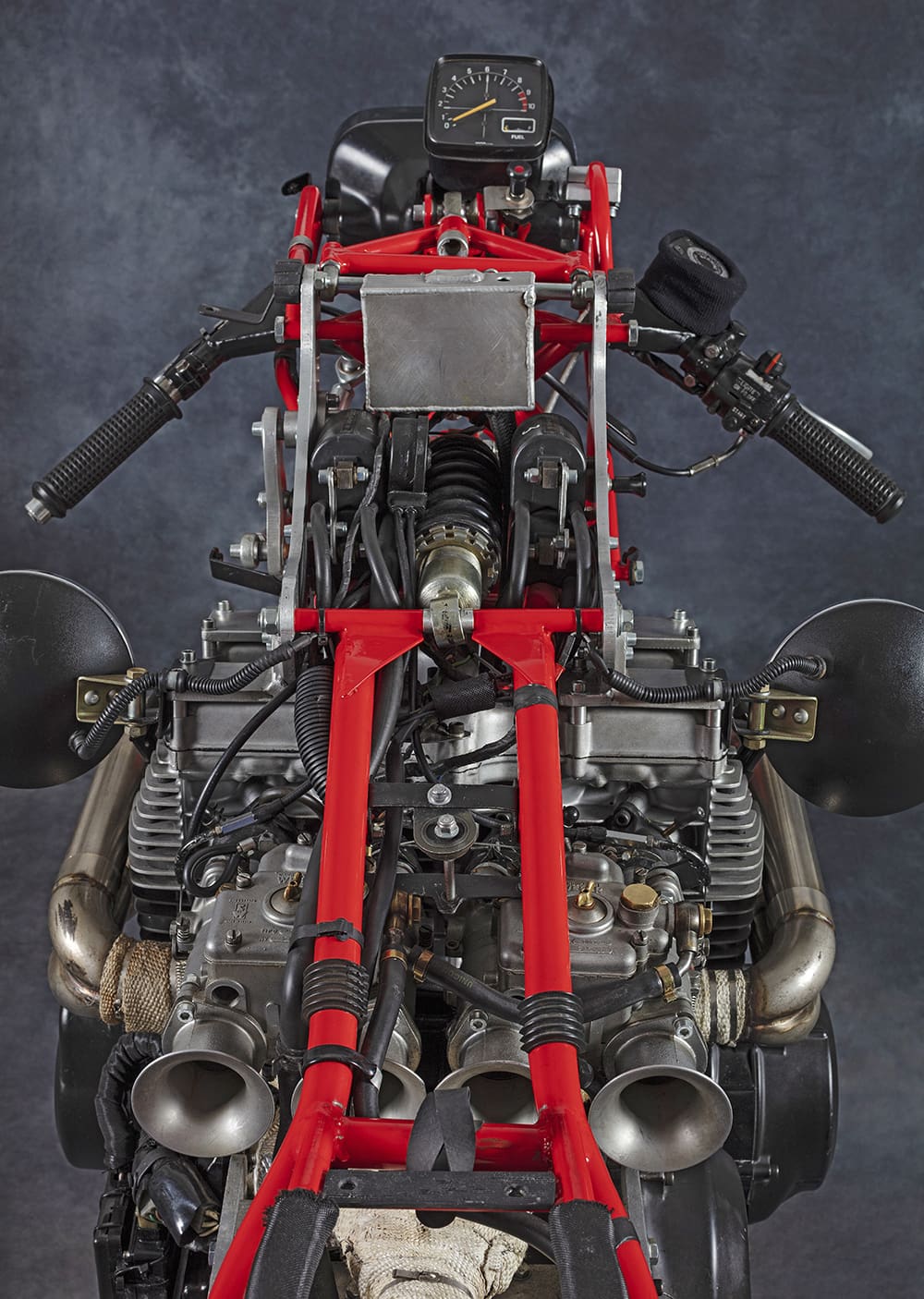

In a brilliant piece of lateral thinking, Fior had adapted open-wheeler car technology to motorcycling suspension along with his own strong but minimalist chassis. At this time designers were only just starting to grapple with the inherent weakness of conventional motorcycle front suspension by adding fork braces and experimenting with anti-dive systems.

Fior’s bold and brave approach was way beyond the conventional parameters. The idea was to completely separate the functions of steering and suspension travel. This would allow the rider to brake later while the chassis geometry and wheelbase length remained constant.

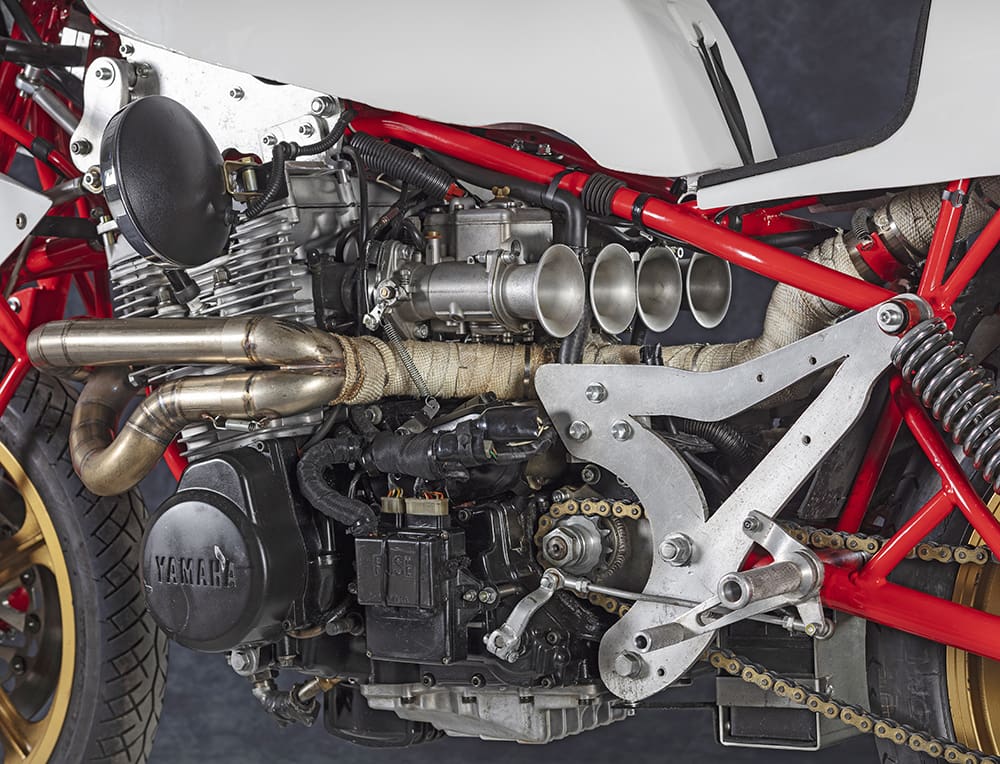

To create this effect, a car-like suspension unit fitted inside the wishbone structure, helped move the whole system in a vertical plane like car suspension, not at an angle like a conventional motorcycle fork. Fior claimed his design was stronger, lighter and gave infinitely more adjustment options than existing production forks, and early in 1979 he used his own TZ250 Yamaha as a test mule for his revolutionary new front fork made from tubular steel.

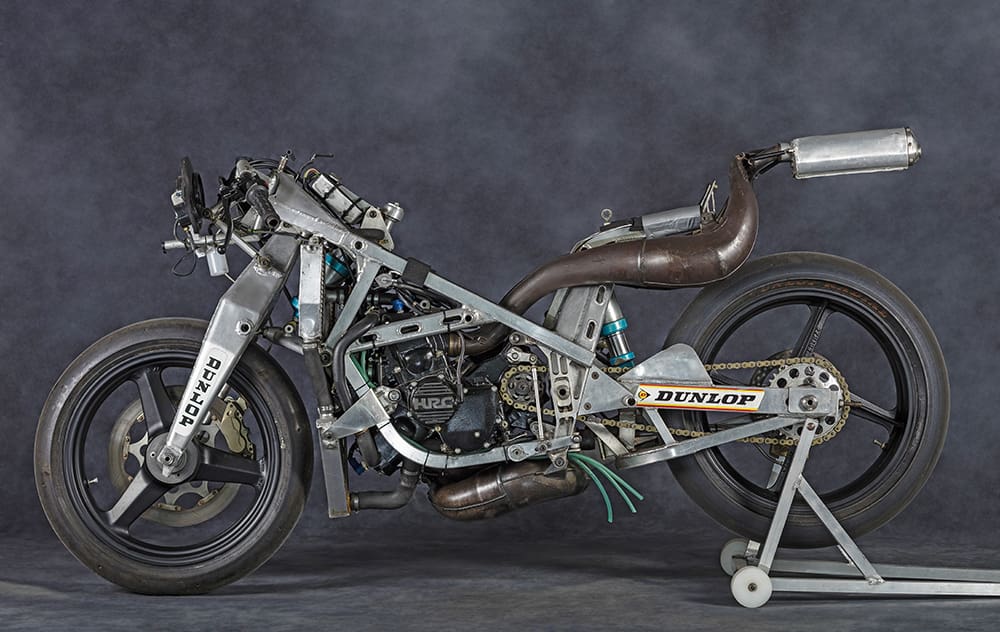

It would have been an achievement just to create the front end, but Fior fronted the 1979 Bol d’Or 24 at Le Mans with a complete motorcycle of his own design incorporating his experimental fork.

This included a frame that used the engine as its main bracing, with large sheets of aluminium locating the front and rear suspension. Combined with Fior’s own bodywork, the whole machine weighed just 175kg dry, nearly 100kg lighter than a standard shaftdrive Yamaha XS1100!

The exhaust snaked back through the frame and exited under the seat for extra ground clearance, while the battery and electrics were carried down low beside the engine.

An indication of how highly-regarded Fior was, even at this early stage of his career, came with legendary French Yamaha importer Sonauto providing a factory-sourced, race-kitted engine.

This included twin-plug heads and a lightweight crankshaft. Other modifications that helped take power to 89kW (120bhp) included twin Weber 40DCOE carburetors, while a chain rear-drive conversion turned what Yamaha had originally conceived as a touring motorcycle into a proper racer.

The spline on the engine’s right-angle drive unit can accept a TZ750 countershaft sprocket. It was possible to match this with a TZ rear sprocket and wheel, although other options were available from European manufacturers of magnesium wheels. Of course, it also required a different swingarm, but that was no biggie for a master fabricator like Fior.

Sadly, Fior’s brilliant work on his first endurance bike ended with a huge crash in free practice. His team was forced to revert to a standard chassis with the race engine, but he still managed to finish eighth overall, and first in the Superbike category with Pierre Guy.

Not one to dwell on the past, Fior quickly moved on to the next version of his Yamaha XS1100 racer. This had a modified frame and an alloy blade wishbone front suspension, which would become a Fior trademark over the next decade.

The revised version had varied success before the engine was returned to Yamaha-Sonauto, after which Fior, following changes in the rules of World Championship racing, started using Honda RSC1000 race engines.

Fior’s first endurance bike would have remained forgotten but for the efforts of an Italian collector. A long-term admirer of Fior’s vision, creativity and perseverance (and owner of the two later 500cc GP Fiors) he acquired the complete chassis of the 1979 racer from the family. Meticulous reconstruction even involved building up a replica of the XS race engine with as many of the period parts as could be located.

This one-off racer is a true gem of motorcycle history and is shown here in complete detail.

Grand Prix innovator

Fior spent the 1980s fine-tuning his theories, developing his suspension system on a variety of motorcycles in Grand Prix racing. Every bike built was different from the previous one, because Fior was never satisfied and on a constant mission to improve performance.

His first GP bike was commissioned in 1981 by Sonauto and powered with a Yamaha OW54 engine. It was never raced because Yamaha management considered the design too bold and advanced so forced Sonauto to abandon it.

Fortunately for Fior, payment for this stillborn project provided him enough money and the incentive to jump into the big time. In 1982 and 1983 he constructed a series of Suzuki RG500-powered racers with outside sponsorship. Entered into selected rounds of the 500cc GP championship, one actually qualified on pole at Fior’s home track at Nogaro in the hands of Frenchman Jean Lafond but didn’t score any world championship points.

In 1983, Freddie Spencer won the 500cc world title on Honda’s new V3 and suddenly the RG500 was heading for obsolescence. So in 1984, Fior switched to Honda RS500 engines for his square-tube, alloy-framed racers.

Fior created shock-waves by building the lightest racer in the 500cc class, just 117kg minus fuel, compared to the factory NS500’s weight of 125kg. His 500cc entry listing was under the Honda name and it wasn’t until 1987 that Fior was officially recorded as a maker of motorcycles in either the entries or results.

By now he had enlisted ex-Yamaha privateer Marco Gentile, who would become a friend and key rider in Fior’s GP quest. The Swiss racer also brought Marlboro sponsorship, which was a huge boost for a privateer team.

As well as the 500cc class, Fior also developed bikes in the 250cc class with Yamaha, Rotax and Aprilia engines and ridden by such French riders as Christian Boudinot and Jean Louis Guignabodet. The RS500-powered machine featured here won the French championship with Thierry Rapicault in 1987. It was a good year for Fior. Gentile became the first official Fior rider to score a world championship point on a similar machine with his 10th place in the San Marino GP at Misano, Italy. A third rider was fellow Frenchman Herve Guilleux.

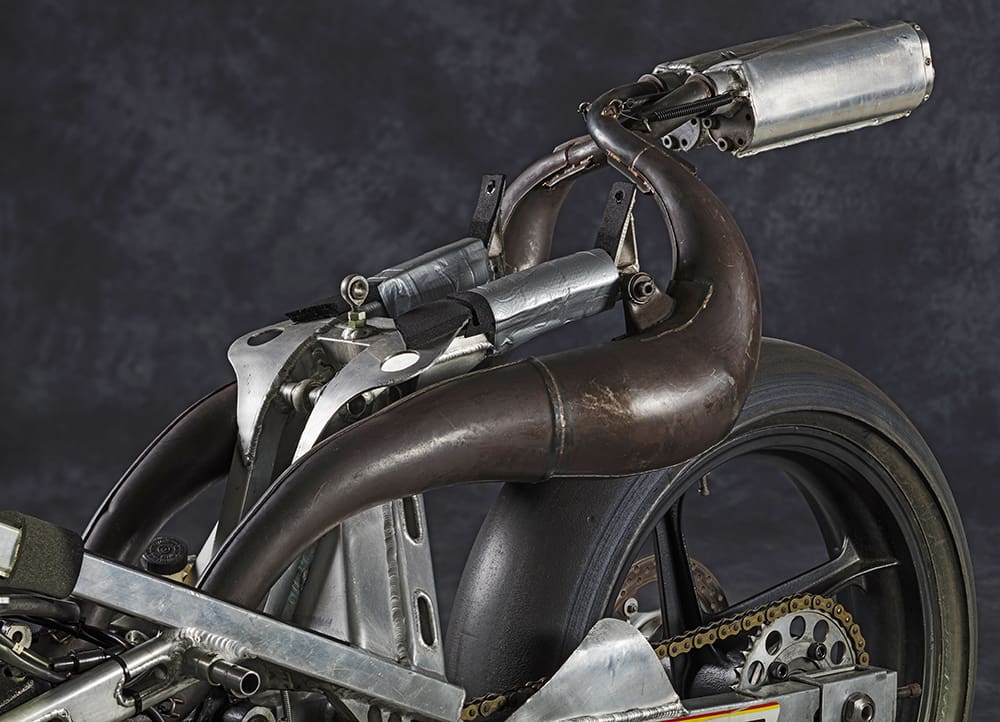

Compared to Fior’s very first tubular front fork, the version which adorns his 1980s racers looks a lot more evolved even if the technical concept remained the same. The linkage system has been simplified and the shock absorber mounted vertically, not horizontally as on the first bikes.

The chassis itself was by now fully adjustable for trail, wheelbase and ride height. As well the pivot point between the rear suspension and gearbox output shaft could be altered to suit various track conditions.

By now all Fior systems were using Fournales compressed air shock absorbers front and rear. Based in the south of France near Toulouse, company founder Jean-Pierre Fournales had a lot in common with Fior. He was a forward-thinker who had had a career in the aerospace industry and a hobby as a motocross racer. Fournales’ innovative, strong but lightweight suspension units were based on aircraft landing gear. Fior drew freely on French technology and his obsession to create a truly all-French racer reached its ultimate goal in 1989.

The French GP challenger

Now with strong Marlboro sponsorship and rider Marco Gentile showing GP points-scoring potential, Fior fronted the 1988 season with his most radical racer yet.

Its 127kg weight (minus fuel), 112kW (150bhp) power at 12,300rpm and 300km/h top speed was the equal of any of the leading factory machines from Honda, Yamaha or Suzuki.

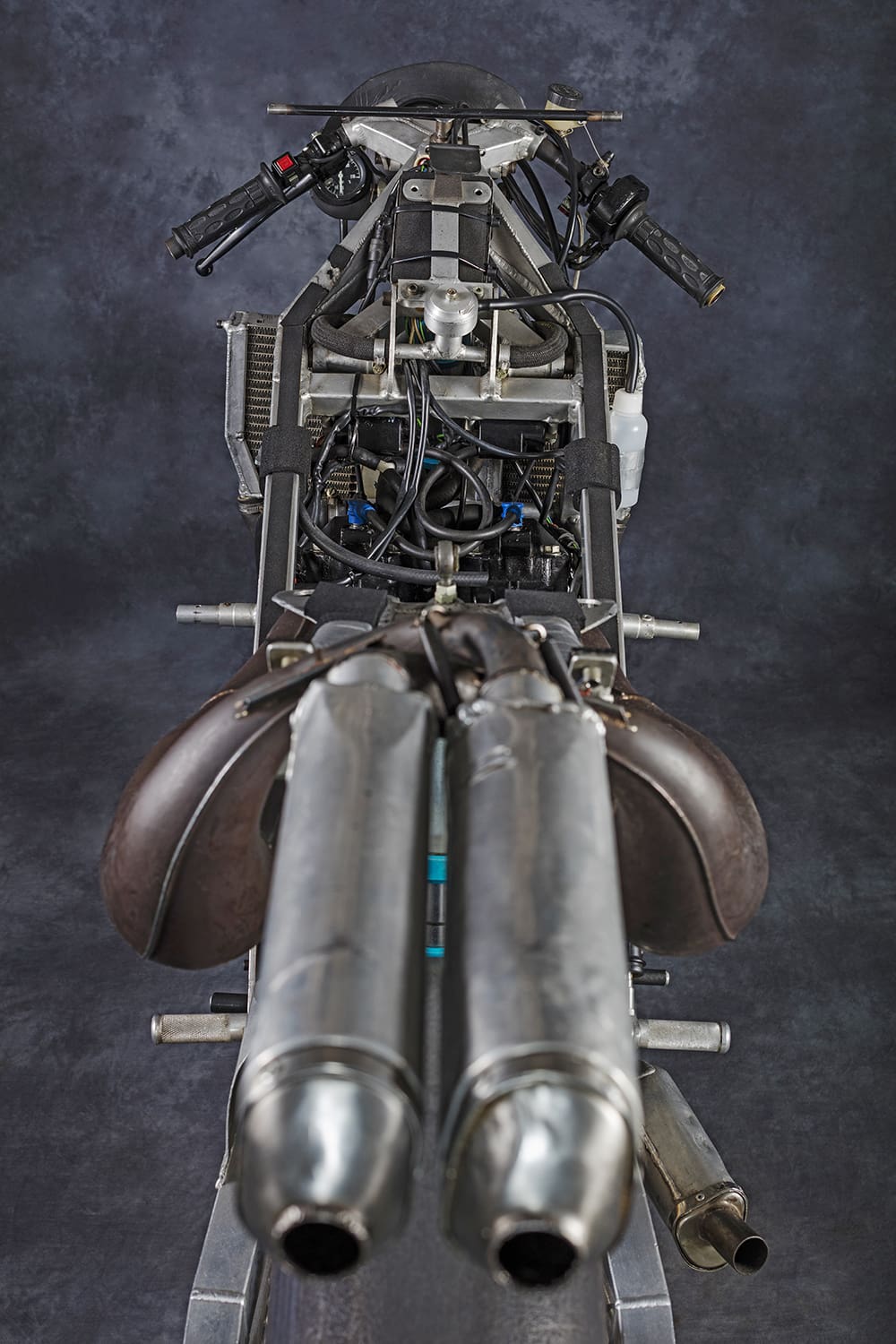

However it was an entirely French motorcycle. Fior’s frameless chassis and wishbone fork, along with Fournales suspension, was powered by a JPX-Yamaha engine.

JPX was a Le Mans-based company that primarily made reed-valve and four-cylinder two-strokes for sidecar racing based on a Yamaha design. One was adapted for Fior’s GP 500cc project using a six-speed gearbox and the clutch off a TZ500.

Fior took chassis minimalism to the extreme, with front and rear suspension bolted to the engine. Clever positioning of the radiators and exhaust expansion chambers resulted in a compact and agile motorcycle.

Gentile eventually scored eight championship points that season with a best result of 11th at Brno, Czechoslovakia.

In the following year, 1989, the frame was modified and extra water cooling installed. Four curved radiators were cleverly mounted around the engine and their extra capacity reduced the power loss experienced on earlier versions of the engine as its heat increased during the races.

With its fairing on, the Fior looks like a typical 500cc GP two-stroke of the era. The aerodynamics dictate a bulky fairing and tailpiece, with the front fender also aiding air flow. Stripped of its bodywork, it becomes instantly obvious the huge amount of thought and physical effort put into getting bulbous expansion chambers and large radiators to fit without compromising ground clearance.

Then there is the matter of the wishbone front fork, with all its complexities contained in what looks like a simple structure. By now at least 10 years of development had been poured in this aspect alone.

Like previous seasons, Fior and his team had their ups and downs. But by season’s end the unthinkable had happened. Gentile was tied with Cagiva’s Randy Mamola on 33 points. This meant the one-rider Fior team finished just five points behind the multi-million-dollar Cagiva operation in the manufacturers’ points table. Not bad for a low-budget team with funds so tight that Fior had sourced the radiator overflow bottle from a local pharmacy near his workshop. Or was the renowned joker simply playing a prank on his paddock rivals!

Gentile’s best result was fourth at Misano but seven times he finished just outside the top 10. Fior’s design seemed to have finally been vindicated but one major limit all along had been tyre technology. The radical front fork put different stresses on the front tyre than conventional telescopic suspension.

Being such a small team, Fior didn’t have enough influence with even French tyre manufacturer Michelin to have a special compound formed to suit his design.

Season 1989 became both the pinnacle and swansong of Fior’s 500cc Grand Prix career. Marlboro revised its sponsorship priorities at the end of that year and another more personal loss helped end Fior’s work.

In late 1989, Gentile died in Nogaro near Fior’s workshop while he was testing the TZ350-powered go-kart in which Fior used to follow his bikes on the track to watch their handling. Abandoning GP motorcycle racing, Fior continued development work in other areas, eventually founding Nogaro Technologies in 1995.

He designed mountain bikes with aluminium monocoque frames and suspension, motorised skateboards, electric vehicles and a Renault race car, the Spider Fior F99 with which a one-make championship was organised. He also designed and built several flying prototypes and gliders, which became a new obsession.

Sadly, his new passion would be one risky venture too many. In December 2001, aged just 46 years, Fior died when he crashed his plane in fog approaching the runway at Nogaro on a return flight from Paris.

He may be gone, but his creativity lives on in these three restored examples of his genius.