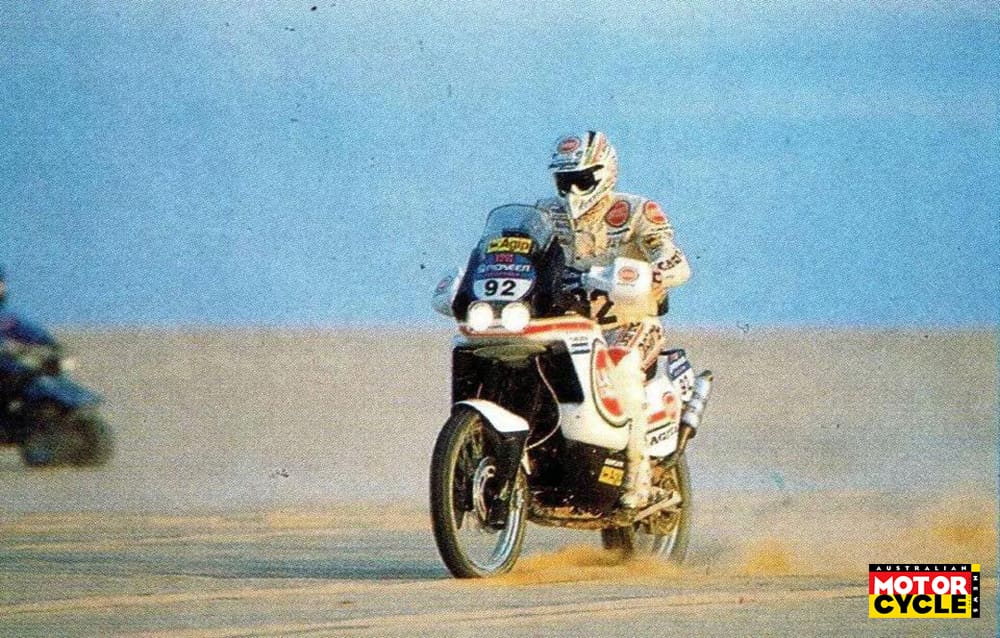

Edi Orioli’s January 1990 Paris-Dakar win on the Lucky Explorer Cagiva Elefant 900ie began a huge 12 months for Ducati and its owner Cagiva. By the end of the year Raymond Roche would deliver Ducati its first Superbike World Championship on the 851/888 Superbike. Meanwhile Cagiva pressed on with its Grand Prix 500 campaign, with riders Randy Mamola, Ron Haslam and Alex Barros.

This victory, in the 12th running of the Dakar, was hugely significant for Cagiva and Ducati, which had spent the past six years challenging for an overall win but never quite achieving it. To win the Dakar, Orioli’s Cagiva Elefant first had to survive 12,000km, including nearly 8000km of brutal competitive stages, from Paris in France, to Dakar in Senegal.

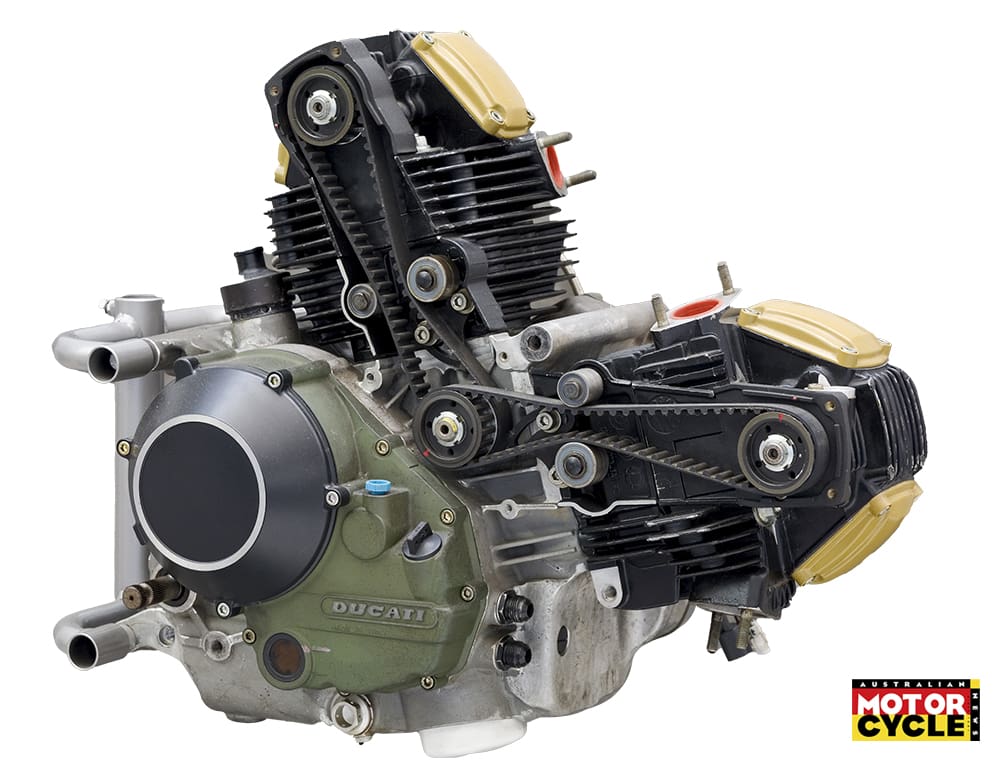

The engine powering Orioli’s winning machine was vindication of the strength of Ducati’s new 900cc V-twin. It was based on the 904cc twin that was powering the 900SS model helping Ducati revitalise its roadbike sales under Cagiva’s ownership. It would soon be used in Ducati’s upcoming M900 Monster, which would launch a whole new motorcycle market segment.

While in many ways it was a modified production engine, the effort, underwritten by Lucky Strike cigarette sponsorship, was similar to the technical effort that goes into today’s WorldSBK championship.

But then production Ducati engines in the 1980s were race winners straight out of the box. With a lineage traced back to the early 1980s, and to the world championship-winning TT2 600s and F1 750s of the mid-1980s, Orioli’s Elefant employed many technical lessons learnt in long-distance racing. These included a victory at the Barcelona 24 Hour endurance race at Montjuich Park and numerous Isle of Man TT wins, not to mention the high-speed torture test of Daytona’s speed bowl in support races and the actual 200-mile main event.

How trick was it?

Italian journalist Vanni Spinoni revealed the secrets of Orioli’s Lucky Explorer Cagiva Elefant 900ie in a major feature published in Moto Tecnica magazine soon after the 1990 victory.

He discovered the engine was actually 944cc, achieved by boring the cylinders 2mm oversize. Compression was reduced slightly from 9.2:1 to 9:1 to compensate for the quality of fuel available during the race.

Head porting was standard (although it’s well known that the 900SS engine comes from the factory with optimum settings) and valve sizes were standard 43mm inlet and 38mm exhaust.

The dry clutch was also standard and ran an exposed cover. The thought was the spinning plates would expel more sand and dirt than would get in and having it open would cool its operation. Likewise, the oil capacity at 3.5 litres was also standard, but a much more abbreviated lower sump casting replaced the large, finned 851-type. This allowed the engine to fit better into the compact frame.

Weight was saved by the use of magnesium engine covers (even Honda did this with its earlier XR600 Dakar single-cylinder racers). Ditching the starter motor, along with its drive gear and heavy battery, shaved several kilograms off overall weight.

The six-speed gearbox of the production 900SS was swapped out for the earlier five-speed cluster, with second and third gears changed to be closer in ratio, vital to get power to the ground in unstable conditions. The five-speed gearbox also had much wider gear teeth and so was more robust to handle the huge loads imposed by jumping off dunes and blasting through rocky valleys.

Termignoni supplied the tuned, 2-1 ‘open’ exhaust which Spinoni said sounded “like a trombone”. Peak power was 49.8kW at 8000rpm and maximum torque 70.6Nm at 5000rpm. A standard 900SS at this time produced 54kW/74.7Nm.

The secret weapon

The engine might have been slightly detuned for reliability but its management system gave it a huge advantage over a production 900SS. Rather than the stock Mikuni carburettors, the Lucky Explorer used the Weber/Marelli ignition-fuel induction system first seen on the 851 Superbike. The rear cylinder head was reversed so the system could be fitted neatly into the engine layout. Weber/Marelli had been developing similar systems in F1 car racing and Ferrari’s sportscars so the technology was at an advanced stage.

The 851 throttle bodies were restricted to 42mm to allow for the 900SS engine’s two-valve head design. The management system included engine temperature monitoring with an air pressure regulator. The engine’s ignition could advance more than 50 degrees if required, vital for smooth running at low throttle openings.

In a nutshell, the system ensured optimum ignition spark and fuel delivery at all times, whether the Lucky Explorer was plonking through a rocky dry creek bed or pounding over open desert at 185km/h.

However, as Spinoni explained, there was much more development ahead. He said Michelin needed to develop a new tyre as the factory was working on getting more torque from the engine to make it become “like a Caterpillar tractor”.

In the frame

While the engine didn’t look that much different from a standard 900SS, the frame was unlike anything else seen on a Ducati. A large, curved 30mm-square box-steel backbone stretched over the V-twin engine, with beautifully machined aluminium brackets and rear suspension links. It was strong and compact with a sturdy aluminium square-section swingarm. The rear subframe was easily removed to gain access to the engine’s rear cylinder head.

Front suspension was the best Marzocchi off-road fork available with 45mm stanchions and 290mm of travel and the axle mounted on the leading edge of the fork. The top-shelf Öhlins rear shock provided 290mm of travel. A 21-inch front wheel and 18-inch rear wheel used Excel aluminium rims, Nissin supplied the brakes and Michelin the tyres. The bodywork included carbon-fibre panels while instrumentation was secured in beautifully welded aluminium brackets. Overall weight was 180kg.

Navigation employed both aviation and Peugeot World Rally Championship technology and the hardware was returned to its maker soon after the Dakar. Around 65 litres of fuel were carried, adding around 45kg of weight but giving a range of around 450km.

A special inlet port pulse vacuum system pumped fuel from the lower section of the tank back up to the injectors.

Three of these Dakar racers are known to have been built in 1990. There may have been a couple more used for testing and lead-up events to the Dakar. Around eight engines in total existed (several earmarked as back-up spares). Two complete racebikes are still known to exist. One is in Ducati’s museum and the other in the private collection of the team that ran them in the Dakar. Both feature Orioli’s race number.

Cagiva-Ducati won the Dakar again in 1994 with Orioli. By this time the regulations had changed to make all race bikes more standard in specification to production models.

So, the 1990 winner marks a unique moment in Ducati and Cagiva’s history which the factory celebrated by releasing a lower-spec Elefant 900ie replica of just 999 examples.

The victor

Edi Orioli seemed to be a natural at reading the terrain and maps. And he knew how to ride fast while conserving the motorcycle he was riding. For example, in one 850km leg of the 1990 Dakar, he wasn’t fooled when officials put the start flags on the wrong track as he had studied military maps of the area. He easily won that section while strong rivals, including Stefan Peterhansel, got hopelessly lost.

That stage, called Agadez, set him on the path to eventual victory. It was his second win after victory with Honda in 1988. Orioli would go on to achieve four wins in total.

After retiring he was asked about the secret of his success. He replied: “Understanding how you can win is something subtle, there are moments that follow a long preparation. Moments of decision, strategy. And once you do it you know how to do it again.

“I have to say that I miss the adrenaline rush of an event like the Dakar and today I often search for that emotion. For example, I’ve just been to the Isle of Man TT where I finally breathed real adrenaline. There it all makes sense: It is not an event, it is a rite.”

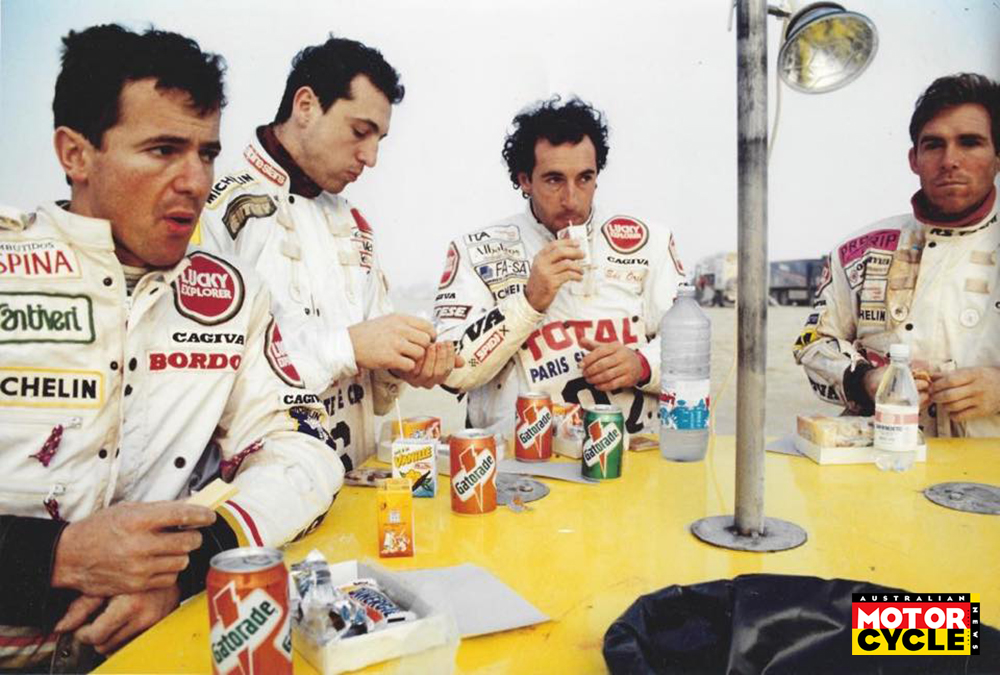

The team

Cagiva contested the Dakar through Team Azzalin, also known as CH Racing, with owner and founder Roberto Azzalin managing the operation. He had links back to the original formation of Cagiva and was involved with its rapid expansion and success in motocross that led to two world 125cc championships in the early 1980s. At this time Cagiva was considered the world’s fastest-growing motorcycle manufacturer.

Azzalin first discovered the Dakar in 1982 when he ran across it unintentionally while on a cycling holiday in Algeria. Cagiva started working on a prototype of the first Elefant at this time and by 1984 Azzalin had poached Hubert Auriol to abandon BMW and join his new team.

Auriol was fast and just two years into his involvement with Cagiva was leading the Dakar until he crashed and broke both ankles on the penultimate stage. The death of another team rider, Gian Paolo Marinoni, after a low-speed accident in the 1986 Dakar also hit the team hard. However, it continued, using various versions of Ducati’s 750cc V-twin before the race-winning 944cc Elefant created history in the hands of Edi Orioli.

Roberto’s son, Fabrizio who manages motocross teams today, says the Dakar Cagivas of the 1980s were “full prototypes, like MotoGP now”.

When new rules from 1993 required “marathon” bikes built closer to production versions, Cagiva-Ducati supplied CH Racing the standard parts which they built up into racers. Around 20 were built each year, including one that came to Australian Ducati importer Frasers but was never raced.

Fabrizio says his father “worked 345 days a year for the remaining 20 days of the Dakar”. He regards Roberto as “the last one standing of his generation”. Now 83 years old, he is still involved in motorcycle race preparation and cycles 60km every few days.