Adventure riding comes to three-wheelers as Ural empties its options list into the Sahara

Ural Australia has added an Adventure-spec sidecar to their range so that tricyclists who want to go bush no longer have to DIY. There are many home-brewed hi-mile rough-road rigs out there, but it’s fair to say that no two are the same and each one represents one owner’s view of what’s needed to tame the wide brown land.

Predictably, the Russians have a slightly different view.

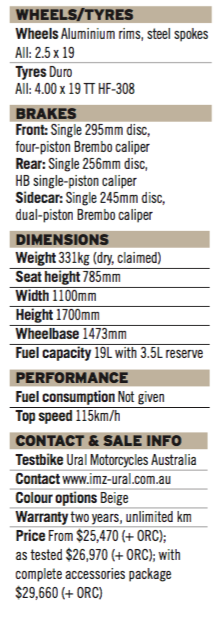

The Ural Sahara isn’t actually a new model, but is rather a Ranger with The Lot. Think of an Adventur-ish accessory and chances are it’s already there; practically the entire catalogue of bolt-on goodness has been tick-boxed for this model. Long-range LED spotties? Check. Barkbuster-style handguards? Check. Spare wheel? Check. Shovel? Check – yep, there’s even a robust folding shovel as part of the Go-Bush Ural, lashed to the body with mil-spec rubber bands. You’re expected to supply your own poo-tickets though. The spare wheel’s a 19-inch rim, as are both front and rear wheels, but before just swapping out a punctured tyre, the relevant brake disc will need to be mounted too: all three are different sizes.

But even up-specced to the brow-vents as it is, the Sahara model sold in Oz isn’t as all-terrain as it is elsewhere: draconian and antiquated ADRs require that all sidecars registered in Australia be fitted to the left side of their towing bikes and this means that the very popular two-wheel drive system is denied to us. YouTube is awash with examples of what mad Russians do with their 2×3 off-roaders.

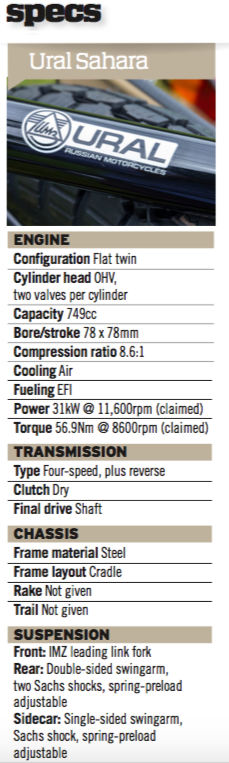

Underneath the flat beige paint and multitudes of bolt-ons, the Sahara is a lightly reworked Ranger. It’s still an air-cooled 750cc boxer twin to which fuel injection and Japanese electronics have been very successfully adapted, although the latest version gains one lonely extra horsepower (0.75kW). Torque, however, rises by a useful 10 per cent. None of the power or torque numbers are especially high, but just like a Rolls-Royce, they are ‘adequate’. That’s exactly where any comparison to a flashy car ends.

The basic architecture of the Ural remains unaltered since Stalin was an altar-boy: flat-twin OHV donk a la BMW circa 1968, an engine-speed dry clutch, four-speed gearbox (plus reverse) and a shaft-drive rear end. Having both kick and electric starting on a bike is a rarity nowadays, but Ural can make that claim. The fitment of fuel injection, Japanese switchgear and electricals and a trio of Brembo brakes – a single 295mm disc on the front wheel, a 256mm on the rear and a 245mm rotor on the sidecar’s wheel – brought the brand into the 21st century. Now the fitment of an LED headlamp and twin LED driving lights puts Ural right at the cutting edge of motorcycle design. Or not – okay, we’re just kidding about that bit – but the fitment of LEDs does show the factory isn’t entirely mired in the past. Heritage is one thing, stagnation entirely another.

Other upgrades found on the Sahara include a 16-clickstop steering damper, a wider track, new black coating on engine and drivetrain, a new front engine casing with a spin-on filter, a jerry can and rack, the optional dual seat to replace the surprisingly comfy standard tractor-style saddle, luggage rock-shields on the mudguard marker lights and headlamp, a small Givi windscreen, racks on the sidecar’s nose, mudguard and above the spare wheel, and even a 12V socket inside the sidecar. This last looks decidedly dodgy, a real Heath Robinson lash-up with a cheapy fusebox – but at least it’s easily accessible. Much more impressive is the huge toolkit which even includes two vials of touch-up paint and, ominously, a first aid space blanket. Then there’s the moveable spotlight on the sidecar’s nose –useful if you fancy a bit of from-the-saddle night-time pig shooting. Just ask the passenger to aim the light.

Blast-from-the-past items include a big tyre pump and a glove box set into the steel tank. And of course there’s a cavernous, lockable boot. Before you need to start packing things into the sidecar’s passenger space, you can load up the rear luggage compartment with enough stuff to make a trailer-tugging Gold Winger green with envy. A serious extra-cost option is a winch – so serious that the mounting for one is a standard Sahara fitment.

Touch the starter button and the 8.6:1 compression twin instantly spins to life with fuelling that seems spot-on all the way. The single throttle body responds eagerly and the clutch lever action is light, predictable and progressive. Typical for an engine-speed clutch, gearshifts are slow, deliberate affairs with distinctly Churchillian gaps between ratios – and even then there’s usually a fair degree of clunking and grating. The gear lever is a heel-and toe shifter slightly confounded by sidecar mounting hardware that the designers intended to be on the other side of the bike. While the lever’s an awkward shape, using the heel for upshifts and the toe for down does make the process less cringeworthy at the lights.

Things are no more relaxed for the other foot – the rear brake lever is simply not where a normally assembled human could realistically get it in a hurry. Reverse is selected with the right heel, and magic, and elves put the transmission back into neutral first, if you want to go forward again. Actually, reverse gear on an outfit is a seriously handy feature – on a motorcycle, it’s just todger-tugging onanism, but on a three-wheeler it’s either a cool talking point or a life-saver if you’re stupid enough to have nosed into a downhill park.

The riding position is quaint: although the seat height is only 810mm, there’s lots of space to the pegs, but the bars are curiously curved and the tank is almost not between your knees, it sits so low on the frame. You get the feeling the 19-litre tank could be almost doubled in size without being intrusive. The strap-on Givi screen wobbles and dances and was a clear candidate for modification with a machete, but did survive our relationship.

Riding a sidecar isn’t for everyone, and riding one off-road doesn’t guarantee you won’t crash. Not needing to put your feet down when trickling over/through/past some gnarlier bits seems great in theory, but in reality, it’ll just get you a long way past your usual chicken-point and reward your efforts with a real doozy. For example, there’s nothing like a sudden hole in the track on a steeply cambered slope to have the sidecar looming large over your left shoulder: while the sidecar’s heavy, the bike is heavier and given enough inclination, it will tip over to the right. Or the left if you try hard enough; on a machine that weighs over 350kg, you’ll always be significantly lighter.

Before you get it that far though, the Ural is remarkably competent – you’re reminded that the company has been doing this for a very long time. The leading-link front end gives one-handed steering at almost all road speeds but without the flighty nervousness of many DIY leading-link suspensions. Suspension travel is, frankly, minimal – a few inches at best and it’d be fair to say that suspension movement is on the rugged side of firm, at least on our virginal test bike. After many more bareback break-in miles, it may become suppler, but it’ll never be voluptuous and plush. That said, it doesn’t jar or leap around on bumpy roads and nor is it soggy, flaccid and limp-wristed on smooth roads, remarkable given that there are two shocks at the front, two at the rear and a fifth on the sidecar’s single-sided swingarm. You still need to practice the craft of sidecar cornering – brake late into rights and power on around lefts – but the solid chassis removes a lot of anxiousness. Adding weight in the sidecar improves matters still further and she’ll be useful around camp too, licking the dishes and fetching a stick.

But on dirt roads, the Sahara is a hoot, even in one-wheel-drive: hooking a fistful of urge will have the front end pushing wide until the rear Heidenau tyre eventually loses grip and starts to spin. Then you steer it on the throttle, using heaps of shoulder and body english to initiate and maintain a drift. Of course sensible, mature sidecarists simply don’t behave like that.

The Ural has an air of enduring solidity about it. It feels like it is built of real metal and there is some aluminium, almost no plastic and absolutely no carbon fibre. It’s the sort of vehicle that will be mentioned in wills by bald solicitors – perhaps more than once.

For the rider who likes a bit on the side, who has a companionable partner or dog or who simply likes to get away from it all while taking it all with him, there’s now a real store-bought alternative to an adventure bike – and as the one most likely to bring beer, you’ll be welcome everywhere.

TEST STEVE KEALY PHOTOGRAPHY MARK DADSWELL