1. If I want my bike to pop monos easier, do I need to gear my bike up or down?

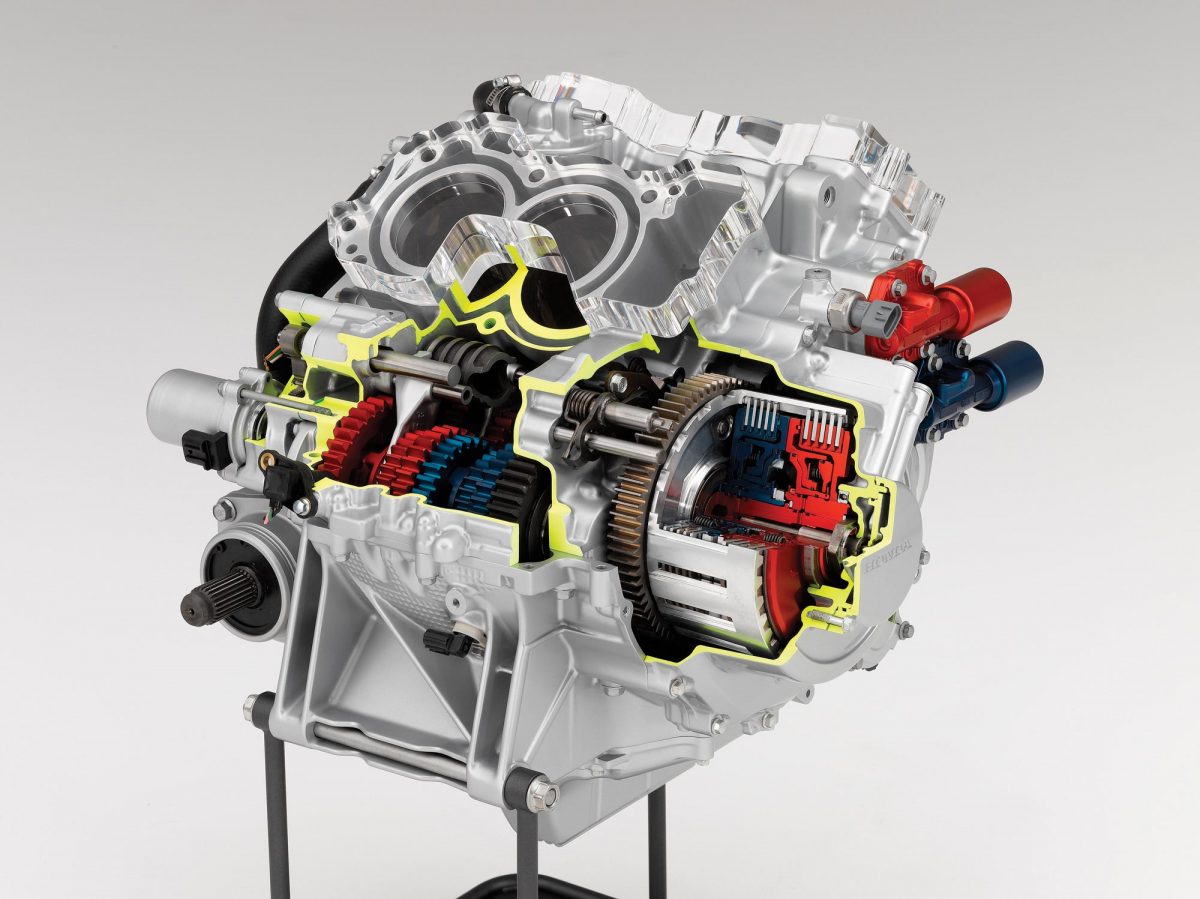

That depends. The language of gearing can be a little confusing. If someone suggests you ‘gear it up’ for a certain track, they could be telling you to fit a larger rear sprocket or to fit gearing which gives you a higher top speed in each gear. The problem is, those two scenarios are exact opposites.

Although the latter is arguably the most commonly used meaning of ‘higher gearing’ or ‘gearing up’ (gearbox ratios or sprockets which result in a higher speed at any given engine rpm), it’s best to talk strictly in terms of actual sprocket and gear sizes – how many teeth it has – to avoid any confusion.

As for popping monos, obviously, that’s a form of delinquent behaviour we would never condone here at the Horror. (Just try first gear, mate.)

2. So if my bike revs its ’rod nuts off when I’m cruisin’ on the highway, I can just fit smaller sprockets to make it mellow, yeah?

Not quite. A smaller rear sprocket will reduce the engine speed for highway cruising, and will also give you a higher top speed if the bike is powerful enough to reach maximum rpm with that gearing. You can achieve the same result by changing the front, but there you’ll need to fit a larger sprocket.

Within the range of sprocket sizes fitted to most motorcycles, a change of one tooth on the front sprocket is roughly equivalent to about three and a half teeth on the rear sprocket in terms of its effect on the final-drive ratio.

If you’re looking for a big change in engine speed, it’s best to change the front sprocket, which will have less effect on chain adjustment and the bike’s wheelbase.

3. I heard all the big race teams change the internal gearbox ratios for every track.

True blue?

Not true, Blue. MotoGP and Moto3 bikes are the only major racing classes left that allow gearbox ratios to be altered to suit each track. MotoGP allows 24 alternative ratios, plus four primary-drive ratio options (the gears connecting the crankshaft to the gearbox), while Moto3 has 12 and three choices respectively. As a consequence, gear ratio optimisation is a dying art in the world’s race paddocks.

Superbike and Supersport 600 classes previously enjoyed open regulations with regard to gear ratios. But it was in the era of the two-stroke when this dark art was most critical to a rider’s performance on race day. The relatively minuscule torque outputs and narrow powerband characteristic of 125 and 250 GP machines required the meticulous calculation of internal ratios by the mechanic – and deft use of the gear lever by the rider to keep them on the boil. It was even more so in the days of the 50cc and 80cc classes.

Before the FIM brought in an upper limit of six-speed gearboxes for all road racing classes in 1969, it was common for smaller-capacity GP bikes to have anywhere up to 14 gears. And for each one of those gears, there could be a multitude of alternative gearbox ratios, plus primary-drive sets and final-drive sprockets. With the age of data logging still decades away, it was up the rider to analyse the bike’s performance in each corner on the track and guide the team’s decision on which ratios to fit into the gearbox – something that was often done between each and every practice session.

4. I’m thinking of trying race shift, but I don’t actually know why…

The reason for using a reverse shift pattern gear lever (up for lower gears and down for higher gears), or race shift as it’s known, is to make it possible to shift up through the gears when accelerating out of a left-hand corner at full lean. Getting your foot under the gear lever at full lean on a racebike fitted with sticky tyres can sometimes prove impossible. And if you are forced to stand the bike up mid-corner or over-rev the engine before selecting the next gear, it can affect lap times dramatically.

More generally, upshifts can be faster and more positive when going with gravity. But if you’re thinking of taking the plunge into upside-down shifting, be aware that it’s not easy to jump back and forth between bikes with different shift patterns, and it’s not for everyone.

Besides the fact that learning to use race shift can be tricky and treacherous for most people, performing multiple downshifts isn’t as easy or intuitive. Braking into a hairpin after a long straight, where three, four or even five downshifts need to be executed in rapid succession, takes some fast and fancy footwork, which isn’t as natural as just stamping on the gear lever.

Missed gears and false neutrals are a danger if the gear lever isn’t set up perfectly for the rider’s boot size and foot angle. The gear lever should be set so it’s equally easy to get your foot above and below it; and, if adjustable, the toe piece should be just above your big toe. Size 12 feet need different gear levers to size 6 feet. It’s so obvious and affects gear-change quality so much, yet still, not many bikes come with adjustable-length gear levers.

Note also that a significant number of racers choose not to use race shift pattern, even some at the very top of the sport.

5. I’ve got a mate who swears that fitting a quickshifter will wreck my ’box, but I reckon he’s talkin’ outta his box. What do I do?

Quickshifters will only damage or increase wear on the gearbox if they are poorly set up. When correctly adjusted to suit the bike and rider there’s no reason gearbox durability should be affected – in fact, they can even reduce wear.

Most popular sportsbikes have plug-and-play aftermarket options available, but if you have an unusual or modified bike, perhaps with fancy aftermarket rearsets fitted, you may need a more universal and adjustable quickshifter kit.

Some quickshifters are more adjustable than others, and some may not necessarily have the range of adjustment to suit all applications. Systems that are purely adjustable for ignition cut time are easy to set up, but it’s often difficult to achieve a satisfactorily clean, crisp shift in every gear. At the other end of the scale are systems that use a switch activated by a strain gauge that is adjustable for sensitivity and can be tuned to alter ignition-cut duration at different engine speeds, and even for individual gears. These are far more challenging and time-consuming to set up and may require professional help to get right, but the results can be well worth it.

If in doubt, there’s always the clutch!

WORDS paul young photography AMCN ARCHIVEs