Pierre Terblanche reveals the almost shocking true story behind how the now-iconic Ducati 916 came to be

Ducati’s legendary 916 celebrated its 28th anniversary in 2022, the firm’s most famous offering having finally stumbled into production in 1994 following show appearances the previous year.

It would go on to transform Ducati’s fortunes: rewriting the rules of motorcycle styling and cementing the company’s status as a formidable force in international racing with an unmatched competition record stretching over the best part of a decade.

Today, Ducati is one of the world’s leading motorcycle brands, owned by a global automotive giant and regularly pioneering new technology, even beating Japanese firms on that front. But rewind to 1994, when the 916 started to filter into showrooms, and the picture was very different.

Despite some race success with the 851 and 888 Superbikes in both domestic and international competition, Ducati’s position on the world stage was the typically precarious one once stereotypically attached to Italian bike brands.

The firm – then part of Claudio Castiglioni’s Cagiva group – could honestly say that the 916, along with the Monster that was launched a year earlier, were make-or-break bikes. Fortunately, both machines went down in history as game-changers.

Following the deaths earlier this decade of both Claudio Castiglioni and Ducati’s former design boss Massimo Tamburini, the number of remaining people directly involved in the 916’s development is waning, but one man – Tamburini’s successor, Pierre Terblanche – was at Ducati during the laboured development of the bike that would eventually become the 916. The soft-spoken South African would head Ducati’s design department until 2007, later setting up his own design firm, working with the likes of Moto Guzzi, Norton, Royal Enfield and Confederate.

“I first started working on the 916 in 1989 when I joined Ducati, but that bike took them seven years to design from start to finish so when I joined the project had already been going for quite a while,” Terblanche told AMCN.

“It went through many iterations and everything was redone a couple of times.”

On taking up his post at Ducati, the 916 wasn’t his main priority. Instead he had to concentrate on its predecessor, the 888 that would debut in 1992.

“I did some proposals for some of the 916 stuff,” he said, “But not straight away. When I joined my first project was the 888, and then I worked on some other stuff. We had a lot going on at the time; 125s, all sorts of things, and I was working on bits and pieces. I worked on the 851 replacement because the 916 was running so late. They suddenly had to do the 888 in something like a month because they were another year behind.”

The 888 was clearly an evolution of the 851 and Terblanche doesn’t seem enamoured with the result of his labours, saying: “It was a rush job, which is a bit of a shame sometimes, but companies seem to run like that.”

It’s a classic now, of course, but his take is: “It would have been a nicer classic if we’ve been able to spend a little more time on it!”

During the development of the 888, and Terblanche’s following project, the almost mythical Supermono racer, the 916’s development plodded along. Some suggest that the Supermono influenced Tamburini’s styling on the 916, and there are certainly similarities in the shapes of the tank and the nose, but Terblanche dismisses the idea that it changed the 916’s look, saying “The Mono was done in isolation, and Tamburini saw it quite late, so I don’t know that it had any influence on the 916 at all really.”

Not that the 916 was designed without taking ideas from elsewhere, and even before work on the legendary bodywork started, Ducati was borrowing elements from rival bikes.

duc00A16

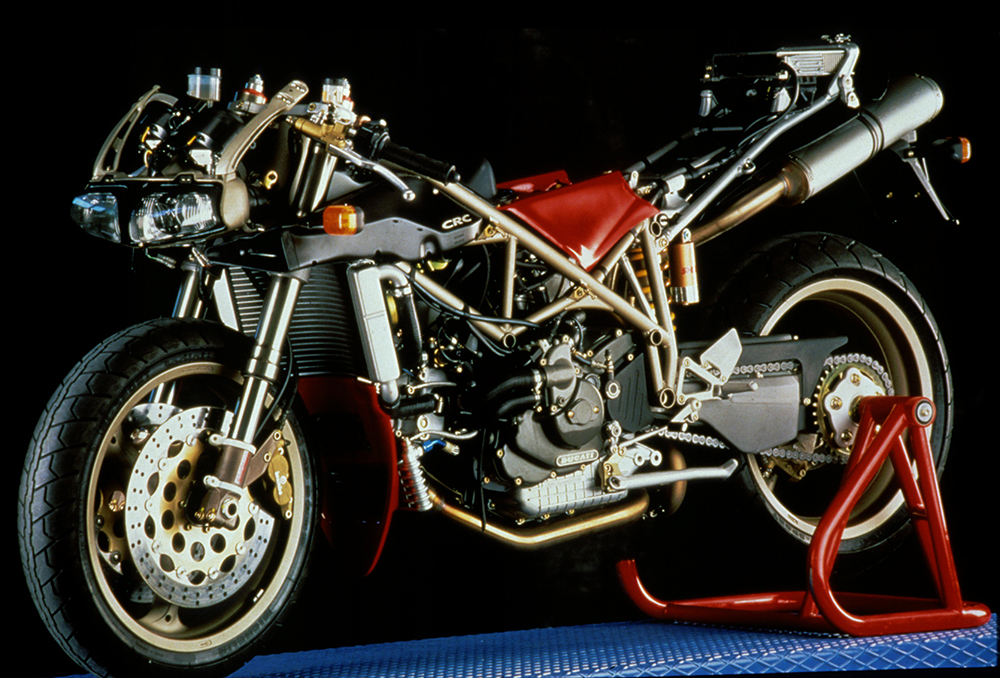

Terblanche said this of his first sight of the 916: “There was no bodywork there yet, they were still working on the chassis and the mechanical layout. The swingarm was basically an RC30 part, reverse engineered, which was all done by hand on the drawing board – there was no CAD back then – and in the model shop.

“There were a lot of wooden models, good model makers and things being crafted by hand. The 916 was modelled in polyurethane foam and body filler, no clay, so it was very different to what people do now.”

So what ideas did Ducati borrow?

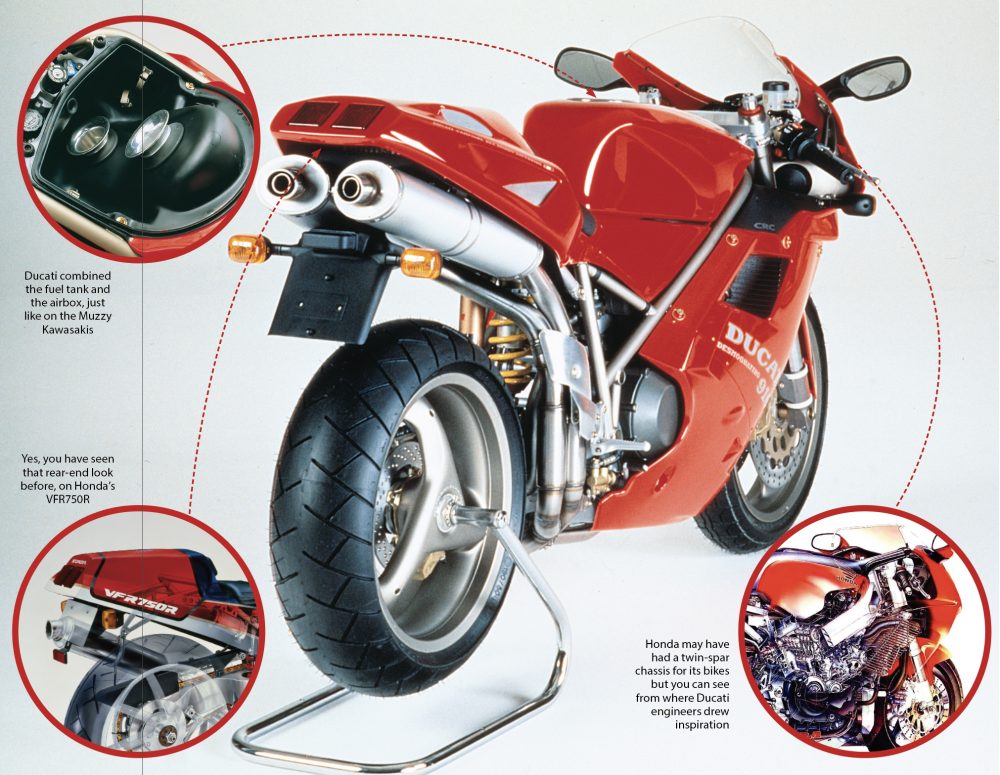

“There are some interesting things about it,” said Terblanche. “Like the tank, which made the top of the airbox. That came from the Muzzy Kawasakis that they were racing in AMA. I read that Muzzy had done it and talked to Tamburini about doing the same. It’s quite a good idea because obviously you gain a lot of airbox volume.”

Elsewhere, Honda provided much of the influence on the 916’s look.

“Look at the tail lights,” Terblanche says. “I don’t know if RC30 tail lights actually fit on there but they are pretty much identical. Tamburini was a huge Honda fan. He really admired Honda, like you should if you know your stuff. So the tail lights are pure RC30 and the swingarm was also basically RC30.

“The under-seat exhausts were NR750, but there are other things too; if you look at the handlebar grips on the NR and the 916 they’re basically identical. A lot of details were borrowed or influenced.

“The NR was the basis for the bike in a way, if you look at it; single sided swingarm, under-seat exhausts, the two headlights at the front. If you look at the NR now, the back end looks very bulbous and fat – the 916 was less bulky, and that makes a difference.”

A less obvious machine influenced the mechanical makeup of the 916; the one-off Ducati 750 F1 developed by Spanish engineer Antonio Cobas.

“The rear of the frame on the first models was not all in tubing, it was fabricated sheet metal that was a bit clunky and heavy,” explains Terblanche, “but then the Cobas Ducati 750 F1 had a beautiful rear frame which influenced the 916. It was a very nice bit of work. Cobas also effectively invented the Deltabox frame before Yamaha did it. He [Antonio Cobas] was a Spanish racing engineer who did some really cool stuff. So that’s basically where the rear of the 916 came from. There were influences from everywhere, that’s how it works; if you see something nice you try to incorporate it.

“If you look at where the battery was situated on the Cobas Ducati, on the right-hand side of the motor, it’s also like the 916. It predated the 916 and inspired it in a way; it was the first Ducati with a full-floater suspension – quite a modern bike for a Ducati at the time.”

Although the 916 received a rapturous reception from the press on its launch, Terblanche – who took over from Tamburini as Ducati’s design boss during the 916’s life – reckons that it never quite lived up to its appearance, particularly in road-going form.

“The 916 wasn’t ever a particularly good bike to ride, unfortunately,” he recalls. “People remember it but it was like a really beautiful blonde who can’t cook, can’t read, but looks pretty hot to walk into the bar with. People don’t want to hear that but the bike wasn’t the ideal roadbike. But it looked great and that will be its lasting legacy.

“When we were working on the 999, I looked at all the 916’s road tests in four or five languages and we tried to fix everything that wasn’t right with the 916 – like some aero stuff and you knocking the shit out of your hands when you steered it, the seat position and a bunch of other stuff.”

Interestingly, he reckons that while the 999 beat its predecessor when it came to handling (and since it continued the 916’s racing dominance in a way that no Ducati superbike since has matched, it’s hard to argue with him on that), there was a lot of luck involved.

“The 999 as a bike was much, much better handling than the 916,” he said, “But that was purely by chance, not by anybody’s clever engineering. What happened was we lengthened the swingarm.

“During the whole life of the 916 we kept the swingarm quite short, but we never had a short swingarm on a race 916. It just didn’t work; I remember Tamburini going up to Mugello when they tested the 916 for the first time, and it just didn’t handle. So they took two swingarms and chopped them up to lengthen the wheelbase by 18mm or 20mm to put more weight on the front, and then it started handling. But in fantastic Italian fashion they never actually updated the roadbikes – they had that flaw all the way through.

“When we did the 999, due to the exhaust run we actually made the swingarm longer by about 20mm, and we moved the rider forward by a few mill and a bit down, and the bike was completely transformed with the same geometry on the front and just a slightly longer wheelbase [compared to the 916]. It actually handled, but nobody really figured it out.”

Terblanche puts the road-going 916’s handling shortcomings down to a tendency to focus on engines rather than frames.

“As we later found out with MotoGP,” he said, “Ducati never really knew how bikes handled well until they got the ex-Aprilia guys in to sort it out. Ducati never really had a lot of testing [for frames], whereas Aprilia did. When I worked at Aprilia, at Moto Guzzi, I asked them why their chassis were so good, and they said it was because they’d never built engines – they used to buy them in – so all their expertise was on the chassis. So their bikes invariably worked really well, and even today with the RSV4, it’s still an extraordinary bike even though it’s getting a bit long in the tooth now.

“You have to remember that Ducati is based in Bologna, near Ferrari, and their engineering school is very good, particularly when it comes to engines. When you go to Aprilia, they have Padova University just down the road. There was a guy there who wrote one of the definitive books on chassis design, and they did a lot of theoretical stuff on chassis work at Padova University.

“And because it’s just down the road, those students are going to go to work for Aprilia. So some companies develop fantastic engines and others end up with good chassis. For many years Ferrari didn’t have good chassis either, and Ducati was like that for a long time in MotoGP, fast in a straight line but they didn’t really want to go around corners very well. Now they’ve got into shape, so the bikes really handle, and that’s down to [former Aprilia designer Gigi] Dall’Igna and I’m sure he must be from Padova University.” (Ed: he is.)

In race form, the 916’s chassis – complete with a longer swingarm than the road version – turned out to be a great handler, though. Again, that was a stroke of luck, says Terblanche.

“Everyone is talking about chassis flex now, but that is something pretty recent. People used to think that chassis needed to be really stiff. So when the guys did the 999 racebike, they actually added stiffening members to the chassis – and it promptly went a lot slower. They also put this huge swingarm on and I remember Francesco Chili preferred to race the 998, or whatever it was at the time, because it had the single sided swingarm that flexed a bit more. I think it’s purely by chance; they just inherited a motor from like, 1978, and they stuck a chassis on it. Later they went on to make the Panigale but it took forever to make it handle because it had a very stiff chassis.

“So the thing about the 916 – and actually the 851 right through to the 1198, because they pretty much remained the same – was that nothing was ever really changed. And that’s why they were quite successful in racing; they kept on developing the same thing.”

And then, 25 years later, there was a limited edition 916-themed Panigale V4, approved by none other than Carl Fogarty

Words Ben Purvis Photography AMCN Archives & BP