Sixty years ago a small, unfancied bunch Texans went faster than anyone before – and made the whole world stand still

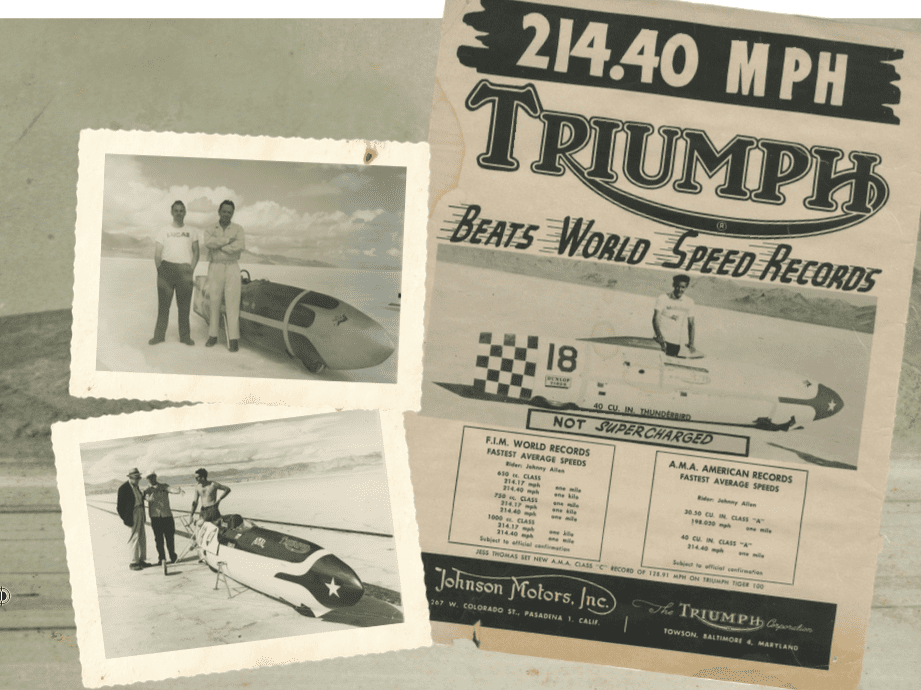

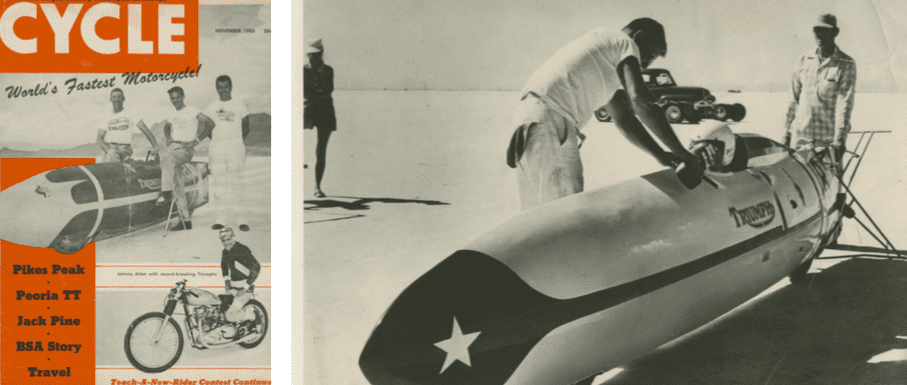

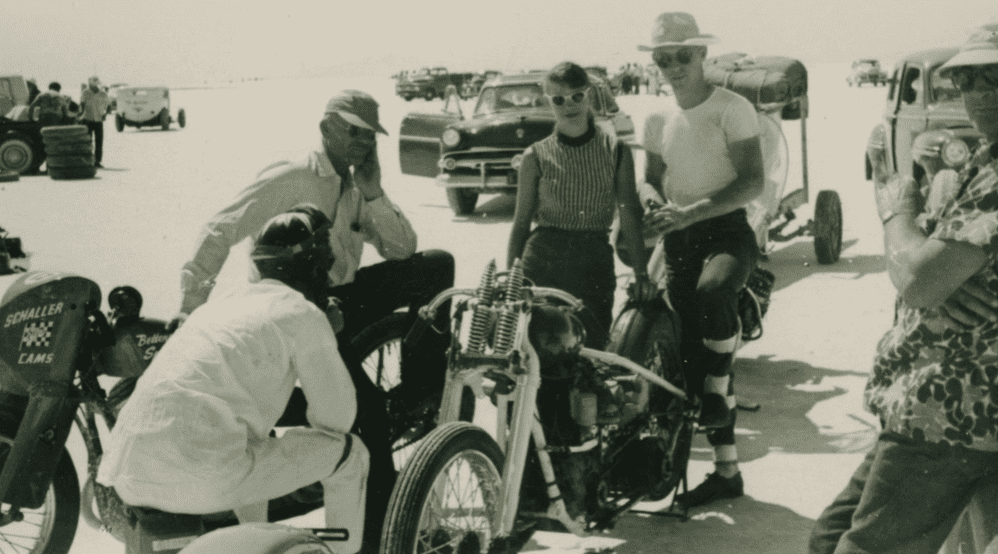

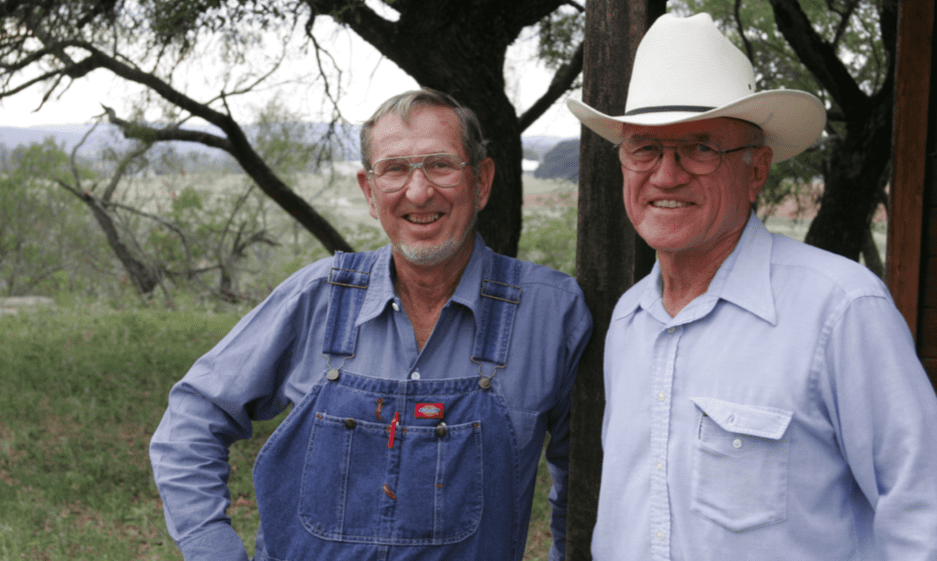

In September 1956, Johnny Allen streaked across the shimmering Bonneville Salt Flats in a Triumph-engined streamliner to set a world speed record of 214.40mph. He was one of a small group of Texans who, with a shoestring budget and a basically stock engine, used ingenuity and quiet determination to beat the exotic machinery of NSU, then the world’s biggest motorcycle manufacturer. His friends Bob Stoker and Charles Mangham recall what it took to become the fastest man on two wheels.

Just a load of talk

Charles Mangham was 20 years old and in the Army when his father began work on the streamliner that became known as the Texas Cee-gar. “It all started one Saturday afternoon at Dalio’s Triumph shop in Fort Worth,” recalls Charles. “After they had shut up shop, Dad used to play poker with Pete Dalio, his top technician, engine tuner Jack Wilson, and Colonel Kohne, a motorcycle enthusiast of German extraction.”

While the dealer shuffled the pack, idle chat turned to how fast a motorcycle could travel. Kohne reminded the Triumph fans in the group that the world’s fastest was an NSU – In April 1951 Wilhelm Hertz had set the world record at 180.17mph on the Munich-Ingoldstadt autobahn with his 500cc supercharged parallel twin, topping the 173mph mark set by BMW way back in 1937.

“Colonel Kohne made the remark that nobody would run that fast on two wheels again, but Dad said: ‘That’s a bunch of bullshit. I can build a motorcycle that will go faster than that’. Well, they all laughed at him so he got up from the card table and said: ‘I’ll just show you’.”

“We had an old cowboy friend,” chips in Stoker. “He used to say that if you wanted Stormy to do something, just tell him it couldn’t be done!”

Born in 1907, James Harold Mangham raced motorcycles when he was a kid – that’s when he got the nickname Stormy – but not everyone was happy with his exploits. “My grandfather was a builder, and he didn’t want his only son to racing motorcycles,” says Charles. “So he made him a deal: stop racing and he’d buy him an aeroplane. Now that is a pretty tempting deal. Stormy hung up his leathers when he got a WWI Curtiss JN4 Jenny bi-plane. With eight hours of flying lessons he went hunting whisky stills in the hills for the law – this was the prohibition era – and went barnstorming at country fairs before flying the US Mail and charters for a company that was one of a group that combined to become American Airlines. Stormy joined AA as employee No 20. But motorcycles still had a pull, which is probably why he ended up playing poker at Dalio’s Triumph shop in Fort Worth.”

With three long haul flights a month he had plenty of time to think about building his first streamliner, but work didn’t start until early 1954. His mechanic Frank Davis welded a framework from aircraft quality 19mm diameter thin-walled chrome moly tubing (we are talking just 0.9mm thick). Stormy had designed the streamliner so that the rider was lying down, facing forward, but had the good sense to try it out before covering it with the glass fibre shell. That’s when he decided that the rider would have more control if he sat upright.

Stormy finally settled on a wheelbase of 2845mm. The shell measured 4775mm long, 686mm high and 559mm broad at the widest point. Ground clearance was 51mm. Both wheels were stock 19-inch Triumph units covered with duralumin discs, but only the rear was fitted with a brake. To keep the profile as low as possible, the steering head was very short and used a single large diameter bearing. There was no suspension. Ready to roll the Texas Cee-gar weighed in at 145kg.

But Stormy’s friends still didn’t rate his chances at breaking the record. “Pete [Dalio] was going to lend him a GP carburettor for the Thunderbird engine,” recalls Stoker, “But then he decided he needed it for another project, so Stormy borrowed one from a BSA.”

Stormy said that they were going to break the record or blow up the engine trying, so strips of old truck tyre were wired to the firewall between driver and engine. A CO2 fire extinguisher pointed from the driver’s compartment into the engine bay. There was also a 10ft [3m] diameter parachute tucked in the tail.”

With the streamliner still in its primer undercoat paint, Stormy set off to Bonneville Salt Flats, Utah in September 1954 with an old Texas Ranger friend to help with the driving. “At the drivers’ safety meeting in Wendover, someone dug Dad in the ribs and told him to stand up and tell everyone about the parachute,” says Charles. “Well, when he said that any machine capable of over 200mph ought to be fitted with a parachute like on his streamliner, everyone laughed … but before long they all had them!

“Dad made a few runs, then a couple of boys from California rode it before the carburettor shook loose. Unofficially, we were timed at 165mph average for the first half of the mile run, so we figured we must have hit 190 towards the end. We did an official run at over 144mph – respectable for a dead-level stock 40 cubic inch [655cc] Triumph engine running on gasoline,” says Charles in his soft Texas drawl.

Word had reached Texas before Stormy got back. “Pete Dalio called a friend in California who told him that the boys really had something on the boil,” says Stoker. “They said there ain’t no telling how fast it would run – hell, it did more than 130 with the carburettor lying in the belly!”

Gathering momentum

That was enough for Dalio and wizard tuner Jack Wilson to get involved. “Jack loved Triumph,” says Stoker. “He could do nothing but think about how to make them go faster, faster and faster. He even made one with a 180°crank. He was always doing something.”

Wilson took one of his methanol-burning sprint motors as a starting point. The 1950 6T Thunderbird engine might have had the standard 71 x 82mm bore and stroke, but the head had been welded and re-machined to take two 1 1/8inch Amal GP carbs in place of the single SU. Bigger inlet valves were modified from ones out of a Harley Model K. Cams, followers and camshaft were all factory race kit. The final drive ratio was 2.8:1.

As the salt flats are 1280 metres above sea level, there was no way a 650cc petrol engine would develop enough power to take the World Motorcycle Speed Record without supercharging. But Jack gave it a little bit of help adding nitromethane to the fuel. With a compression ratio of 11:1, Wilson claimed the engine pumped out over 80 Texas mustangs.

This time Stormy was packing two parachutes – one 864mm and the other 1372mm in diameter. Hastily painted red and silver and christened ‘The Devil’s Arrow’, the Texas Cee-gar was tested on a deserted stretch of highway outside Fort Worth. The results indicated they were ready to go back to Bonneville.

But they needed a rider. Johnny Allen was one of the top riders at that time. “He was a wild-ass flat tracker who got hurt pretty bad out in California when he crushed an ankle.” remembers Charles. “They wanted to cut his leg off but he wouldn’t let them,” adds Stoker. “After the accident he came back home and hung around Dalio’s shop, so when Stormy asked him if he wanted to ride the streamliner Johnny said, ‘Hell, yes!’ ”

Lean and wiry and standing 173cm tall, Johnny Allen began racing 10 years previously when he was 16. “He loved to trade – guns, cars, bikes … anything – and when our friends started getting interested in dirt track, he traded until he got the best bike he could find,” recalls Charles. “We loaded the bikes onto the pick-ups and drove to Louisville. And before the rest of us unloaded, Johnny took off up the dam and looped that new motorcycle and came crashing down. That’s just the sort of rider he was – he couldn’t help but be wild. He’d push the envelope as far as he could.”

Johnny’s association with Dalio began in 1949 when he took 38 firsts in one season on a Tiger 100. Two years later he retired while running eighth in the Daytona 200 when his primary chain broke, but as compensation he took the Texas Short Track Championship title.

But before the Texans were ready for Bonneville, Russell Wright set a new motorcycle world speed record. In June 1955 he powered his streamlined Vincent Black Lightning to 185.15mph over the measured mile on the Tram Road in New Zealand – over 5mph faster than Wilhelm Hertz and NSU.

The New Zealander wouldn’t hold onto his crown for long. The following August Johnny did four runs, clocking 138, 156, 173mph (when he slowed because his goggles started to lift and obscure his vision) and 191mph – the fastest single run ever recorded by a motorcycle. Johnny told his friends that wind pressure at that speed forced his mouth open, and then he couldn’t close it.

There was no way the Texans could afford another crack at the record without a sponsor. With the potential for worldwide publicity in the air, Bill Johnson, president of Johnson Motors, the West Coast Ariel and Triumph importer came on board with financial backing for the team and a $300 expenses cheque for Johnny.

Moment of truth

They were back on the salt just three weeks later on 25 September. The streamliner now had a small screen that wouldn’t look out of place on a jet fighter and new 3.25 x 19-inch Dunlop tyres with a 2mm crown tread flown in from England, with instructions to run them at 70psi in the front and 75psi at the rear.

The salt was far from perfect – rain the previous night had made it too soft to give the perfect traction Stormy would have liked – but it was either now or wait for another year.

At about 9am the winds dropped. Johnny climbed into the streamliner. Inside the pocket of his blue jeans was a lucky silver dollar courtesy of Johnson. Stormy and another of his team pushed the Devil’s Arrow away. The engine spluttered a couple of times and then died. Johnny cursed and damned as the Texas Cee-gar gently flopped on its side. The huffing and puffing pushers ran to lift the plot up and try again. This time the T110 fired cleanly and Johnny was on his way.

But there was a problem with the electronic timing device and the run counted for nothing. Johnny’s catchers turned the streamliner around and pushed him back down the black oil line towards the western horizon. This time everything went perfectly and he scorched the soggy salt, covered the kilometre at 193.88mph and the mile at 192.719. Rocketing down line for the return leg and spinning the engine to 7000rpm he was timed at 193.553 and 191.897mph, to average 193.720mph for the flying kilometre and 192.308mph for the flying mile, as electronically timed by J Otto Crocker of the SoCal Timing Association and refereed by HJ ‘Bus’ Schaller for the American Motorcyclists Association. On the same day, Johnny rode a standard-looking 500cc Tiger to a new American Class C record of 123.95mph on petrol.

“We were pretty pleased with ourselves, although the AMA didn’t think much of us calling the streamliner the Devil’s Arrow,” laughs Charles. “They thought it wasn’t good publicity for motorcycling!”

But because of a technicality the record was not recognised by the Fédération Internationale Motocycliste (FIM) even though it was a lot faster than any motorcycle had ever gone before. To be recognised as a world record by the FIM, the attempt had to be supervised by an American Automobile Association racing official. Although there was an AMA official there – he had been monitoring record attempts by Dodge as well as the Texans – his authority had expired three days before Johnny made his runs when the AMA scrapped the Contest Board that was responsible for overseeing racing and speed records. Unless the FIM changed its rules, there would not be anyone in the US qualified to recognise a world record attempt.

Johnny Allen had told his friends that he was sure the streamliner would better 200mph if conditions were good. “He was coasting through the timed trap at close to 200mph,” says Stoker. “He had another 1000rpm in hand before he reached the timing light, but he was getting wheelspin because of surface water and he had to ease off.”

“You never know whether the water table is going to be up or down, if the salt is going to be like concrete and you can burn a black streak, or mushy and rutted,” adds Stoker.

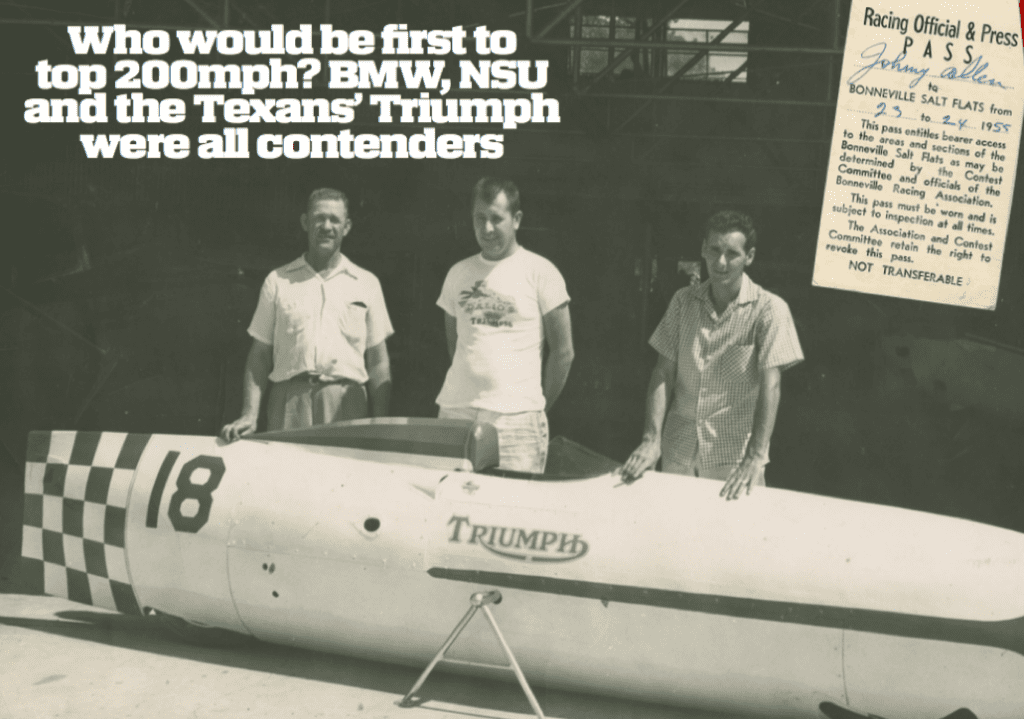

Who would be first to top 200mph? BMW, NSU and the Texans’ Triumph were all contenders, as well as Russell Wright and Bob Burns with their Vincent and Brit rider Bob Berry and his 1000cc JAP. All were expected to put in an appearance at the salt flats the following year.

Salt showdown

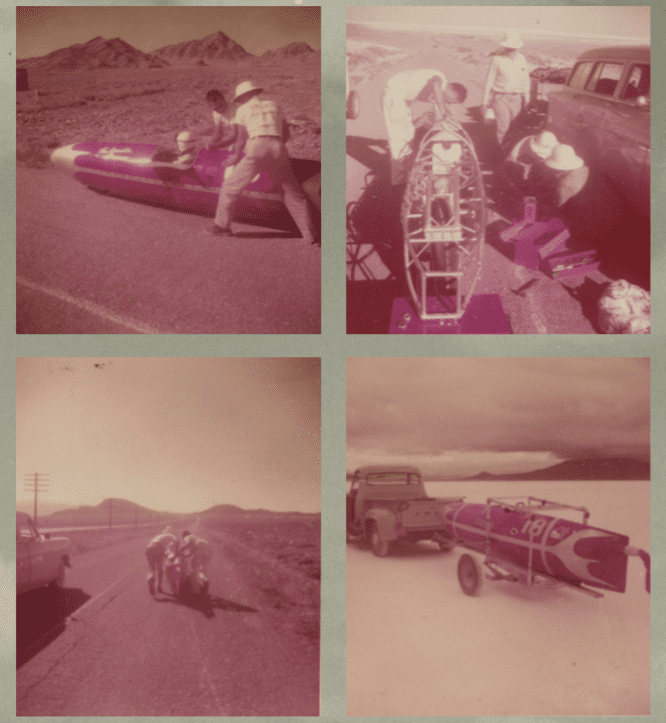

Stormy got to work on the streamliner in preparation for the 1956 record attempts.

The shell was modified with a headrest made from chrome-moly tube, streamlined with doped aeroplane fabric, while the front wheel got an underbelly salt deflector.

Wilson checked over the engine: a new one-piece crank was machined from Natralloy in California but the iron head remained, even though the Triumph factory had offered a specially cast alloy head with splayed ports. Inlet valves remained at ¼in larger than standard (the exhaust valves were always stock) with double S&W springs, and factory Q camshafts and R race-type lifters with more overlap – thanks in part to using 0.5mm clearance instead of standard zero clearance when cold. Compression ratio was lowered to 8.5:1 to take account of the extra nitromethane – they were using 20 per cent mixed with 75 per cent methanol and 5 per cent benzole fed through two 1 3/8in GP carburettors. Instead of the BT-H magneto, Wilson installed a Lucas racing instrument.

The Triumph gearbox now had special close ratios with an extra-tall first. The engine shaft sprocket was 26 teeth (24 is stock), while the gearbox sprocket was almost doubled to 32 teeth to give a final gear ratio of 2.33:1.

And the Ceegar got a new paint job in Texas colours – white and blue bodywork with the Lone Star on the nose, and a red checkerboard tail. In keeping with Bonneville tradition, the streamliner still carried No 18 on the tail.

Wright and Burns never made it to the 200 mark but NSU, the world’s biggest motorcycle producer, had booked the salt flats for two weeks starting 1 August. The Germans were putting in a massive effort to take as many world’s fastest classes as possible and spared no expense, chartering a KLM airliner to fly in 30 riders, technicians, factory staff and journalists – along with timing experts from the Longines factory. The 125 and 300cc records were already in the bag when they wheeled out the DOHC 500. Finished in red on top, with white in the middle and blue-grey below to make it stand out on the salt, Delphin III was the latest version of the 1951 supercharged record breaker. On Saturday 4 August, Wilhelm Hertz blasted back into the record books with an average of 211.40mph for the mile.

“Bus Schaller, the AMA referee, was there,” says Charles, “and he told them that if they could run any faster then they ought to get on with it, because the Texas Cee-gar was coming to Bonneville and was going to blow their record out of the tub.”

But the NSU team packed up and flew home. They wanted their record breaker to be the star of the International Motorcycle Show in Cologne in September.

Johnson Motors had reserved the salt for 4-6 September. On Wednesday 5 and with the streamliner supported in its new ‘wheelbarrow’ cradle, Stormy Mangham pointed the projectile at the distant mountains and started to run along the black oil line that still stained the salt. He knew that success depended on the shape of his streamliner – the small frontal area offered just 20 per cent of the air resistance of the fully enclosed conventional motorcycle that NSU had used.

The start of the timed stretch was three miles away. Johnny dumped the clutch and the Triumph burst into life. Revving to 6500 in first took him past 100mph. The same revs in second accelerated him past 150mph, before he selected third at nearly 200mph and snicked into top about two miles and less than 60 seconds from his starting point. He kept on accelerating down to measured kilometre and mile – they were using the German markers. But all was not well – Allen had run into a bad vibration period. Wilson took the streamliner back to Wendover where they found the front wheel was out of balance.

They were ready to roll again at 9am the following morning. Stormy Mangham took a long draw on his cigarette and blew smoke into the air. Just a gentle breeze – maybe two or three miles an hour at most. Time to take that record.

Stormy pushed his streamliner away again and the engine fired immediately. Johnny ran it up to 7000 in first, watched the tach drop as he slipped into second, and changed into third when the needle hit 7K again. As he selected top gear he just caught sight of the first marker for the measured mile – still about a mile away – and he entered the traps at 6500rpm. The Thunderbird was revving at 7000 just as he passed the second marker. 216.44mph.

Stormy’s team quickly fitted new Reynolds chains for the return run. It was the same again – 6500 into the trap and 7000 out. 212.36mph.

Average for the mile: 214.40. Average for the kilometre: 214.17. The Texas Cee-gar had beaten the record set by Hertz and NSU before the wind had blown their tracks away.

Johnny’s claim to the World’s Fastest was submitted to Tom Loughborough, the British based secretary general of the FIM. As agreed with Loughborough the attempt had been supervised by Philip Mayne of the International Federation of Motorcycle Sport (FIA) which was affiliated to the FIM, and who had checked and approved the timing apparatus built by the Californian Institute of Technology. The record would be confirmed if there was no protest lodged within three months. None was.

Record breakers vs rule makers

But then Loughborough got a call from FIM President Piet Nortier…

Loughborough wrote: “In view of the fact that it was impossible for the new American timing apparatus to be formally approved by the FIM before the record attempts were made, it has been decided by the International Sporting Committee that to make assurance doubly sure, advantage shall be taken of the coming visit of Monsieur Penrose of the FIM to the US in company with Count Lurani, a CSI vice-president, to supervise further tests of the apparatus in question.”

Perous and Lurani declared the timing equipment satisfactory. But even that was not enough. In April 1957 the FIM rejected the Texan’s claim with a single sentence: “Although the accuracy of the timing equipment was not questioned, it did not have the FIM seal of approval.”

Johnny appealed the verdict without success but although it didn’t seem to bother the modest Texan in the slightest, Triumph bosses could smell a rat and wondered if the expensive dinner parties that NSU put on for the FIM Congress had anything to do with it. They sued the FIM, then pulled out of the case after a two-year battle when they were warned by lawyers that it was not a legal issue – the FIM was entitled to impose its rules any way they wanted to. And to prove it, in 1960 they banned the Triumph factory from international events for two years.

But despite the shenanigans at the FIM there wasn’t anyone who doubted that Johnny Allen had not travelled faster on two wheels than anyone else in the world. The American and British press splashed ‘World’s Fastest’ headlines across their pages, and adverts from Dunlop tyres, Amal carburettors, Lodge plugs, Reynold, Lucas, Triumph and Johnson Motors congratulated the Texans and basked in reflected glory.

And when the Triumph factory introduced a hot new 650 twin at the 1958 Earls Court motorcycle show it was named in honour of Johnny Allen and the Texans that built the world’s fastest motorcycle. The Bonneville.

WORDS PHILLIP TOOTH PHOTOGRAPHY PHILLIP TOOTH & JOHNNY ALLEN, BOB STOKER AND CHARLES MANGHAM ARCHIVES