Things have gone pretty well for Remy Gardner this year. The Australian has a MotoGP seat booked with the Tech 3 KTM team in 2022, and his adaption to Aki Ajo’s all-conquering set-up that has dominated both of grand prix racing’s junior categories this season has been seamless, so much so that Remy has won the 2021 Moto2 World championship. We sat down with Remy for a chat about his road to success on the eve of this years Spanish Grand Prix.

“I can’t complain, can I? Everything is going well,” Remy told us on the eve of the Spanish Grand Prix. “A good start to the season. Consistency is key here. Even if there is no podium, I still have to finish races and get points. It’s a long year ahead. We’ve only just started. At the moment it’s just about finishing races and racking up as many points as I can.”

The 23-year old from Sydney has ground out results when necessary and has had the pace to win, Gardner has given it a go without risking it all. Crucially, he hasn’t once looked flustered since becoming the first Australian to lead grand prix’s intermediate category since Gregg Hansford in 1978.

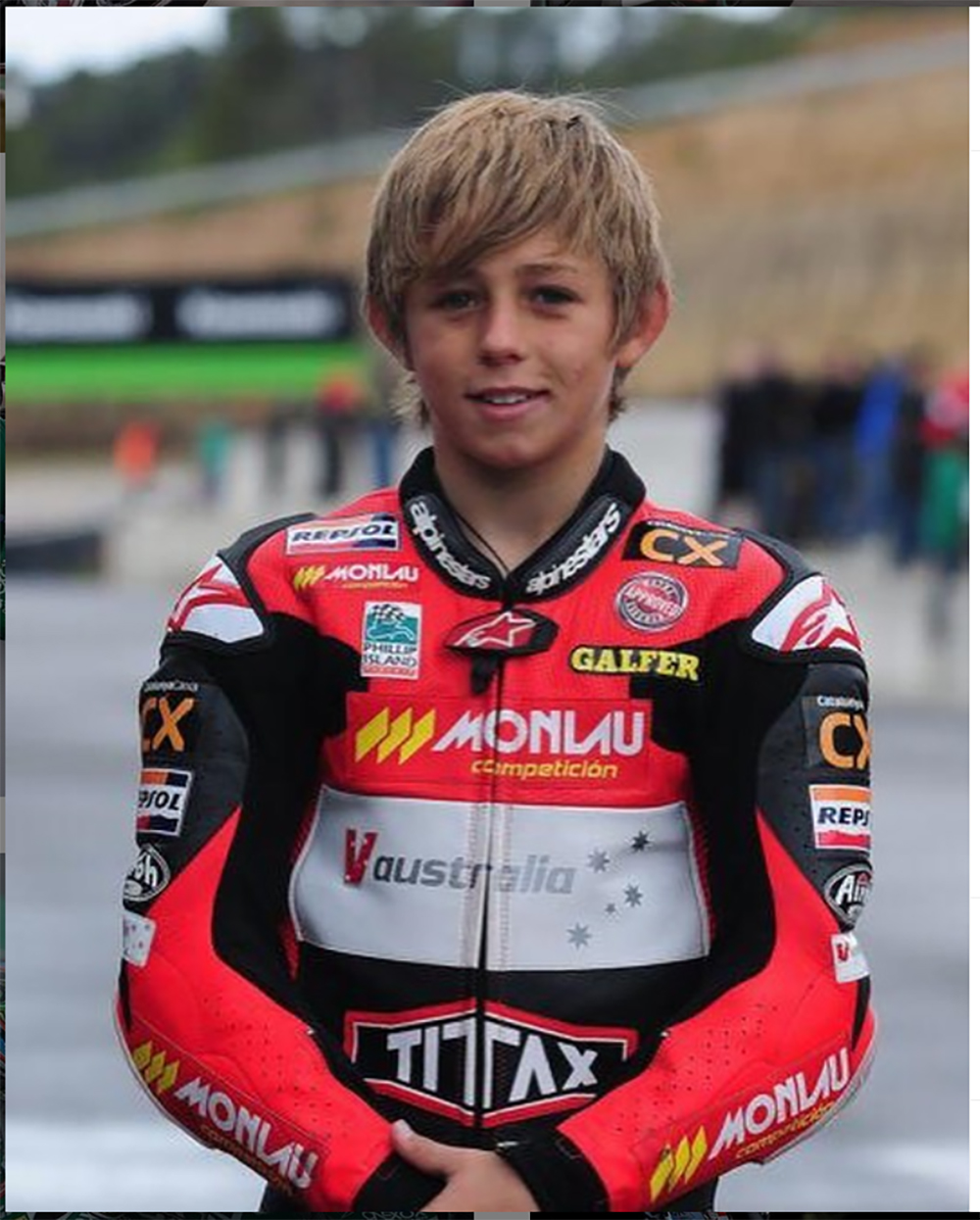

It hasn’t always been like this. Remy has come a long way since he first rocked up in the paddock as a baby-faced 16-year old in 2014 with father Wayne in tow. Then he was shy, a little moody, and unafraid of calling out his below-par equipment (normally with an f-bomb or two). It’s all a far cry from the laidback figure who is now as comfortable in his own skin as he is in front of the media glare, and is careful to talk up the experience and expertise of his technicians around him.

But there were some tough years along the way. Gardner freely admits there were times when he doubted whether he would make it this far. But 2019 was his breakthrough year. A switch to the SAG team, and more importantly to a Kalex chassis – the brand that has won each of the past eight Moto2 rider’s titles – saw Remy start the year well, scoring his first podium in Argentina. He even turned down the chance to replace Johann Zarco in KTM’s MotoGP squad midway through the season, opting instead to become a winner in Moto2 first.

But the season was far from consistent. He suffered seven DNFs. In the autumn of that year, his team ran into financial difficulties. Alfred Willeke, the crew chief Remy charged with his improvement, was poached by a rival team. It all looked a little bleak come season’s end. And many questioned if it was wise to turn that MotoGP offer down.

But for 2020 he came back refreshed. Ajo – Jack Miller’s personal manager – became a personal adviser. His results soon kicked on. Asked what the secret was to his recent run after his second-place at Le Mans, Remy didn’t need to think about it.

“Experience,” he stated. “Crashing. Hurting myself. Flying through the air at 260km/h doesn’t help!” And in our conversation in Spain, he believed the recent run of results was over a year in the making.

“The change probably came at the start of last year. In Qatar we finished fifth. We got back to Jerez and we finished seventh. Then in the second race in Jerez and in Brno I struggled, mainly because of the extra heat. But we were still getting points.

“Then in Austria we were back on the podium. But I did have one crash in Austria, in the first race. I was quite annoyed with myself. It was a stupid crash on my part and it shouldn’t have happened. Going from there, I was kind of angry with myself and said I couldn’t let that happen again. Unfortunately, in Misano I had that crash in warm-up, which was a bit unexpected. I missed those races.

“But when I got back from there it was back to business. I just built on my confidence. You learn from your mistakes, don’t you? You’ve got to keep moving forward.”

Gardner’s recent success has come in spite of one glaring disadvantage: weight. In a class designed for parity, in which all 30 riders compete aboard the same spec Triumph 765 engines, the same Dunlop tyres, the same gearbox and the same electronic aids, stature can play a big role. Remy weighs in at 72 kilograms, two more than the next heaviest rider and seven above the class average. Compare that to chief rivals Raul Fernandez (63kg), Marco Bezzecchi (61kg) and Sam Lowes (65kg).

“One hundred percent, that factor is always there,” he said. “Before I focussed on that a lot and thought, ‘Poor me.’ I always complained about it. But what am I going to do? I’m a big boy and that’s it.

“I’ve tried losing weight, but first of all, I wouldn’t be really happy. And second of all, I wouldn’t have the strength and the energy to finish races. There are other good things about being a bit heavier and a bit bigger. I can finish the races at the end with a bit more stamina. It’s easier for me to move the bike around sometimes. In the end, I focussed on the positives and try to make the most of the weight and try to manage the disadvantages to my best capabilities.

“For sure, there are weekends when it penalises me more. Even in the race in Portugal, I struggled more with that extra heat. I was scorching up the tyres a bit more. You’ve got to learn, move forward and focus on what we can do and not worry about something that is not really changeable.”

His surname may give the impression he’s had it easy with a career in motorcycle racing laid out for him on a plate. And, yes, when he sought a move to Europe as a teenager, he found a seat in the Spanish Moto3 championship, where rides can cost up to 250,000 euros ($400,000) for just one year. But the move from Australia at 14 years of age was far from straightforward. Having set up base in the seaside town of Sitges, 30 minutes outside Barcelona on Spain’s east coast, Remy soon found this wasn’t going to be a walk in the park. A lack of friends, language skills and home comforts all contributed to some pretty lonely years.

“First of all, it’s extremely tough for Aussies to come to Europe and make the move,” he says.

“First, it’s financially. Second, it’s on the other side of the world, with different languages. We did it anyway. Many people probably think I’m here because of Wayne and that’s it. But it isn’t like that. I think sometimes doors have been closed rather than opened. It was tough. There were a lot of years when it was looking really bleak. Also, the difference of level that I had to make up for was incredible. But I hung in there, kept working and stuck out the tough years. I guess it’s all working now. What doesn’t kill you makes you stronger, right?

“(I’ve been) 10 years in Spain. The first two were really quite difficult. I think that’s the same for anyone that does something like that. There was a point when we were thinking about going back home. It’s such a different lifestyle. I didn’t speak the language. I didn’t know anybody. And I was only 14 years old at that point. I had all my friends in Australia. I had all my things there and I’d go surfing all the time. All of a sudden, I didn’t have those things anymore. It was really tough.

“Then in the school that I went to I didn’t really have any friends – they were just weird tennis players. But I started to get to know people and I had a few mates. When I was about 16 or 17 everything was good. I was just being a normal teenager, riding my skateboard with my mates down the streets and getting into all kinds of mischief in the town.

“From about 18 or 19 everything was a bit smoother. I started to learn the language a bit better. Honestly, I’d say the last three years I started to settle in and feel like it was home. I have a Spanish girlfriend now as well, which helps with the language!”

Those early years of settling in were reflected with similar struggles on the track. After three wildcard appearances at the end of 2014, Gardner made his full-time debut in Moto3 the following year. But riding Mahindra’s underpowered racer for CIP, one of the class’s less resourced teams, was more than challenging. He was regularly one of the slowest through the speed traps, and managed just one point-scoring finish – a fine 10th in front of home fans at Phillip Island – all year.

“For sure, that year on the Mahindra was quite depressing,” he said. “It was a tough year. But I think I learned more about how to ring everything out of a bike in that year than in any other. It gave me that self-confidence to think, ‘Man, I’m faster than about 80 percent of the guys here.’ They were just whipping me down the straight. That gave me the confidence but it was also very frustrating. It taught me how to ride the absolute ring out of the bike. And sometimes you need to do that.

“I went back to the Spanish Championship on Moto2 the following year, because I didn’t have a team. That was also tough. But I seemed to adapt quickly to the Moto2 bike. I was starting to get big and with the Moto2 bike that wasn’t really a problem. Then in the CEV straight away, even with a dodgy team, I was on it and winning races. It just came to me quite easily, the big bikes. And it took off from there. Luckily, I got that Tasca ride (in the World Championship) halfway through the season.”

But the toughest moment was still to come. Gardner secured a seat in Hervé Poncharal’s Tech3 Moto2 team for 2017. Viewed in terms of his results alone, it was far from disastrous. Seven point-scoring finishes dotted the year, including a battling ninth place in the rain at Brno. But his 21st overall paled compared to the efforts of then teammate Xavi Vierge, who was 10 places ahead in the championship standings. What’s more, the Catalan took the Mistral 610 chassis to a wet-weather podium finish in Japan. That contrived to put Remy’s future in doubt.

“I’ve got to say: I did have two tough years in Tech3. The first year with Hervé was extremely difficult. There was a point when he was about to not give me a second chance. That was probably the hardest moment for me in my GP career at the end of the first Tech3 year. Xavi was having good results and I was in the shit.

“Then Bo (Bendsneyder) came (to the team at the end of 2017) and in the first test he was quicker than me. I didn’t know what was going on. There was a point when I thought, ‘Maybe this isn’t for me.’

“But at the end of that test at the end of that year I tried Bo’s bike. We tried everything on my bike and nothing worked. We thought, just get on it and do three laps for 15 minutes at the end of the day. I went out and did the fastest ever lap on the Tech3 bike around Valencia with old tyres. I was like, ‘Guys, this is a completely different f***ing bike. What is this?’ They said, ‘It’s the same.’ I was like, ‘It’s not. I can tell you that. Look at the f***ing lap time!’

“So that got the inspiration going again. That got me fired up. I thought, okay, it’s been this frame I’ve been riding all year. That next year they brought three bikes. They said, you’re going to try all of them. You’re going to take the best frame with the best swingarm and put it all together. We did that and I think I crashed it on the second lap and destroyed it in the first test! But we took what we had left and that was the bike. We had some decent results. There were some tough races, and some races when the bike worked better than others. I started getting my mojo together.

“I’ve had a few ups and downs, that’s for sure. The first year on the Tech 3 bike I broke my ankle. Then the next year I was doing motocross and I just blew my leg apart. That was a tough time. I was sitting in hospital thinking, ‘this is over now.’ Right when I needed results to renew contracts, I was sitting there in hospital with a million screws in my leg. I thought to myself, ‘are you going to cry here? Or are you going to get up and try and get back as soon as possible?’ I was working hard every day on the legs and managed to get back on the bike in five weeks – and in the points.”

Gardner has always made riding through the pain sound nonchalant. Away from the track, he relaxes by getting his hands dirty in his rapidly expanding workshop in Sitges. There are no selfies in sight.

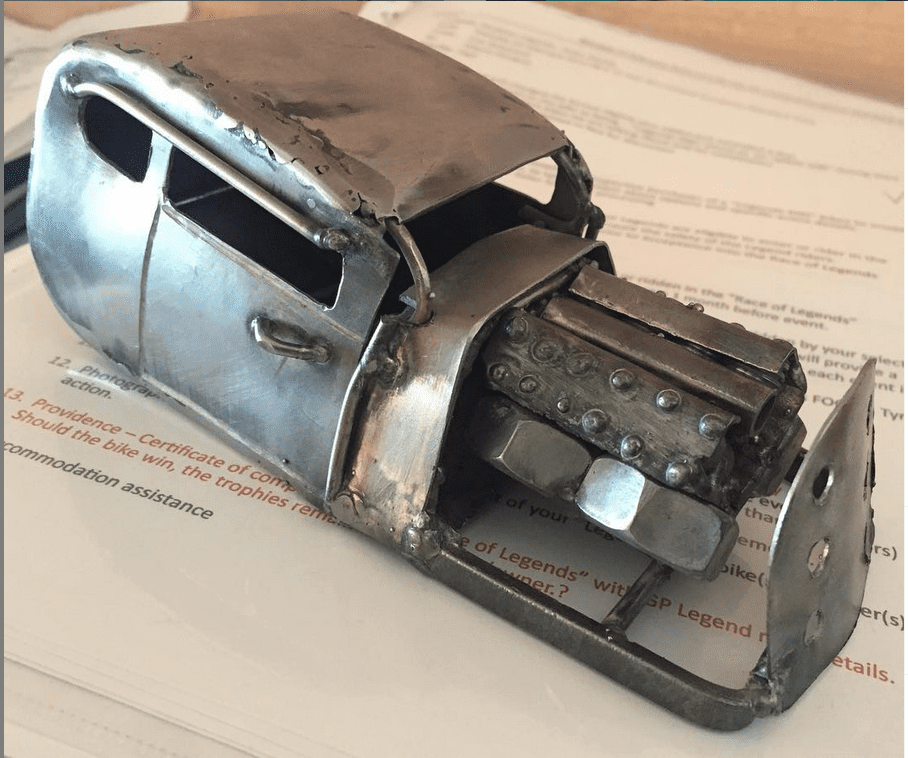

As well as sculpting, skating and surfing, Remy is a keen mechanic and counts restoring old cars among his interests. In a world of Instagram posing and training selfies with designer branding, Remy stands out as something of a throwback. As he told us, that curiosity to build and design has been there since he was young.

“I’ve always been a hands-on guy if I’m honest with you,” he said. “When I was about 10 years old I was on the internet and saw these plans for big garden chairs. I downloaded the plans one day, printed them out and was like, ‘dad, I want to build this.’ So he went out, bought me the wood and the tools – I was only 10. I built this massive garden chair, a beautiful thing that I’ve still got in Australia. I’ve always had an interest, I always worked on my pocket bikes. Usually, I was just breaking stuff in the beginning. But it’s always been there.

“When I left school when I was 16 to go with the bikes and train, I was taking care of my own training bikes. I was doing my own bikes and thought I needed the tools to weld and create parts. I got a welder for my 16th birthday. Then I started making skateboard ramps out of steel and wood. I also did some computerised design for my ramps. One thing led to another. I was doing some sculptures just for fun. And I built a machine that coils up ropes for wakeboarding – like a winch. I bought a go-kart engine and put in this torque converter. I had all these things machined up. I’d then park the thing on the beach, swim out, get towed out of the water and then do wakeboarding on the beach – that was pretty cool.

“Then the engineering side was interesting me more. I built a fast 250 two-stroke. Then I bought my car. And with the engine swap, the (car design) started from there. Bit by bit I’ve been learning how to do more of the engineering. I use a lot of solid works, 3D printing and machining. Now I’ve got a big workshop with mills, lathes and car-lifts. I’m looking at a CNC mill next – it’s a big workshop.

“For sure it helps (to unwind). Everyone’s got to have their little hobby. I’m still training and on the bike a lot. I don’t put it up on social media so much. I don’t really care that much about Instagram and that stuff. For sure it helps me disconnect. Sometimes I just get in there, lock the door and put the phone on silent. I don’t want to hear from anyone. Just leave me alone for eight hours. I can focus on something else and be on my own. It’s quite nice. It helps me disconnect from the bike world.”

That may come in useful when so much talk surrounds his future. Gardner rides in Aki Ajo’s team, but his contract is with KTM. And the Austrian factory was clear that a seat in MotoGP would be waiting for him if his early results this year were up to scratch.

So, does the Australian see a possible ride in the premier class as added pressure or extra motivation? His response is immediate.

“It’s not pressure. It’s just like the golden ticket in front of me, isn’t it? Nothing is confirmed. Step by step. Right now, we just have to focus on ourselves and our job in Moto2. I’m sure if we do our job well, good things will come.”

With the Moto2 championship in the bag, no one can say he hasn’t earned his MotoGP ride in 2022.

Interview Neil Morrison Photography Gold&Goose