Here’s a simple question. Name the Italian motorcycle manufacturer synonymous with transverse, overhead-valve V-twins since 1965? Yes, it’s Moto Guzzi.

Now name the Italian company which revealed a similar V-twin at the International Milan Fair in 1951.

Still thinking? Okay, let’s put you out of your misery. Lambretta quickly became a giant of post-World War II transportation in Italy with scooters inspired by the rugged US military Cushman runabout. It even built racing versions for Italy’s early national motorcycle championships.

But a little-known part of Lambretta’s history was its early ambition to become a major player in Grand Prix racing.

It is only due to the efforts of a passionate and far-sighted Italian two-wheel enthusiast that any trace of Lambretta’s GP adventure exists today.

HOW IT ALL STARTED

Lambretta founder Ferdinando Innocenti’s cheap two-stroke scooters helped mobilise a nation devastated by a world war. The financial return from Lambretta’s massive scooter sales in the late 1940s allowed Innocenti to commission Giuseppe Salmaggi to design a sophisticated overhead- camshaft four-stroke GP racer.

Salmaggi was one of Italy’s leading motorcycle designers of the pre-war era. His Gilera Saturno had become the most sought-after privateer race bike of the 1930s and if his pushrod production- racer Saturno was the benchmark for single- cylinder 500cc Italian racing machinery, his Lambretta V-twin was to boldly go where no GP designer had gone before.

Sure, there were inline four-cylinders from Gilera, and soon from MV Agusta, plus a 120-degree V-twin from Moto Guzzi, but when the Lambretta was first displayed at the 1951 Milan show there was nothing like it on Earth.

WHAT WAS ALL THE FUSS ABOUT?

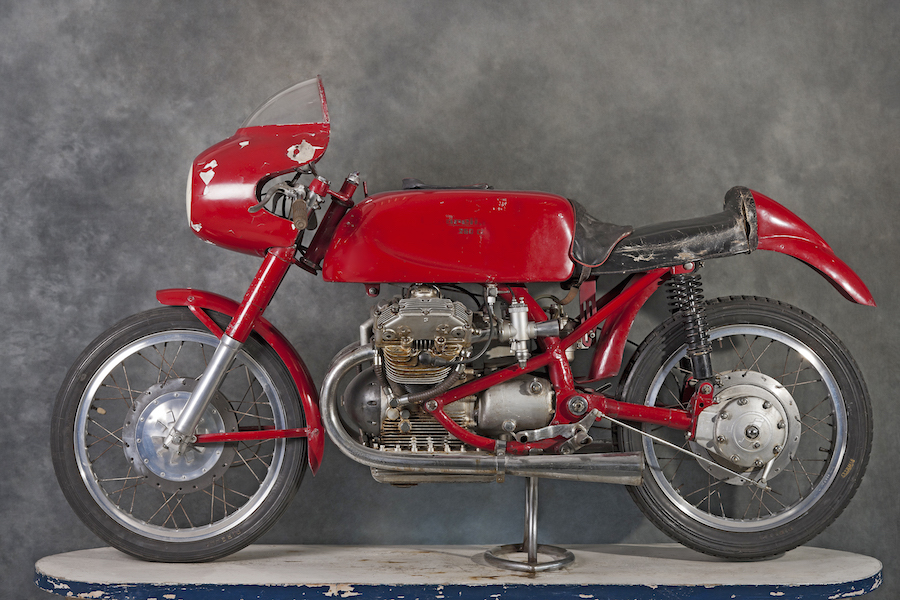

Grand Prix racing motorcycles of the time often looked like a work in progress. Form followed function rather than style leading the way. Not so with the Lambretta. It looked more like a production model than a prototype GP racer. A super-clean unit-construction engine, unique frame design and carefully contoured bodywork combined in a glorious statement of Italian innovation.

The result was described as a “masterpiece in engineering” by a major motorcycle newspaper.

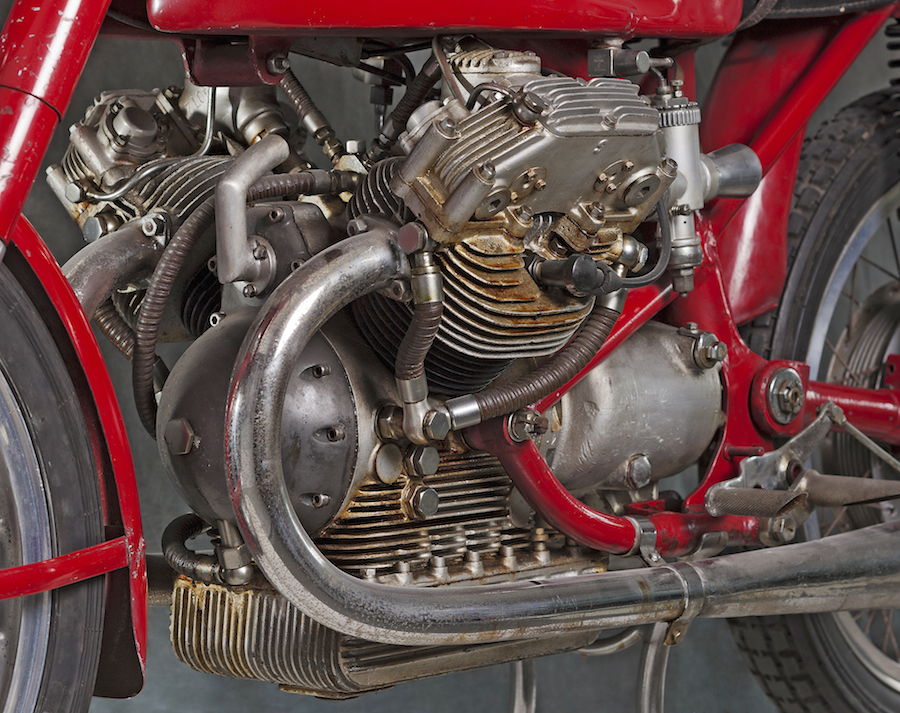

The 90-degree V-twin engine had its crankshaft mounted along the frame, not across it. This pushed the cylinders out into the breeze for better cooling. The 54mm x 54mm bore and stroke gave a capacity of 247cc. Claimed power output was 21kW (29bhp) at 9000rpm on pump petrol with a top speed around 170km/h.

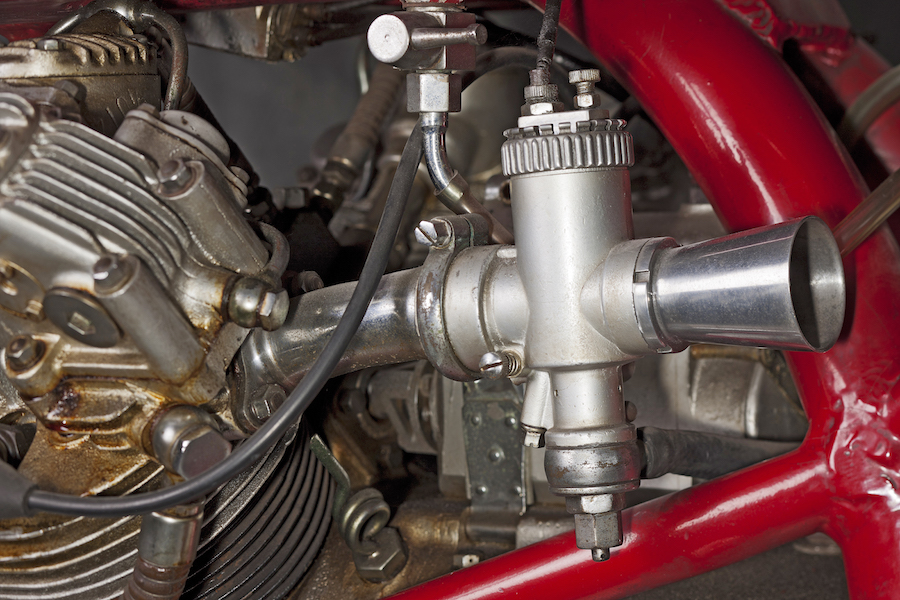

Much thought had gone into the design. Each alloy head contained two valves, controlled by triple-coil springs (not the usual two) and a camshaft that ran in small ball bearings (not bushes) and was pressure-fed oil. The camshaft was driven by a shaft and bevel gears. The bullet-shaped front of the crankcase contained a flywheel-mounted magneto with a rev-counter drive above it. Behind the engine was a five- speed gearbox with positive-stop action and a heel-toe lever.

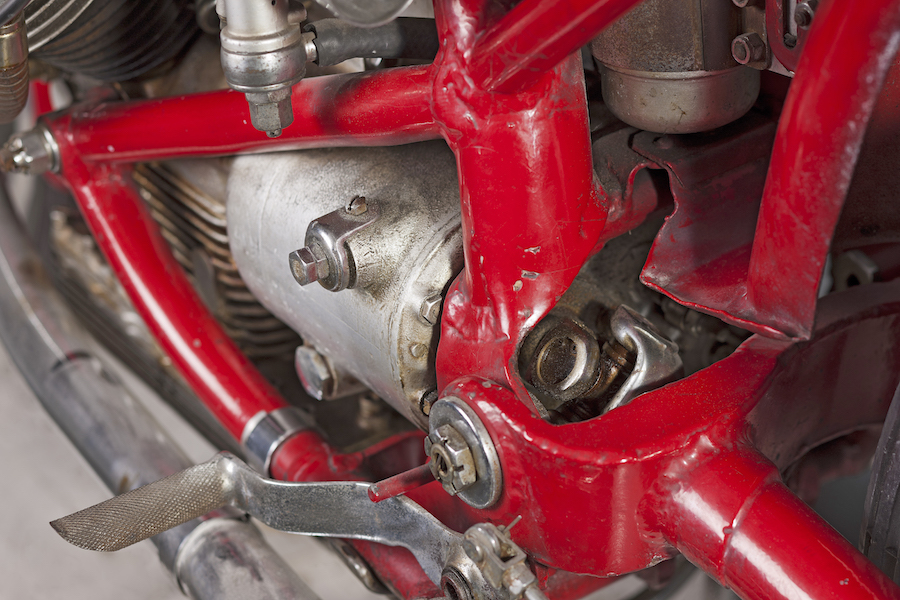

Strangely, rear drive was by shaft, a much heavier option than using a conventional chain.

However, the rest of the little powerhouse was sheer racer: generous finning covered much of the engine and the large oil tank, which had an easy-access filler.

The chassis was as interesting as the engine; a large-diameter spine curved back to steel plates. Tubes ran forward from these plates to hold the engine. There were no front downtubes. The front fork was a conventional telescopic affair, but the rear was a torsion- bar set-up with adjustable friction dampers. Full-width light-alloy brake hubs and 21-inch rims with Pirelli tyres completed the top-shelf specifications.

The Lambretta appeared at the Milan show race-ready, which was no surprise considering extensive testing had been carried out months before on a local track. The 250cc racer was developed over the next two seasons and by the time it was retired in 1953 the engine had evolved into a wet-sump, DOHC unit with a large reservoir under the crankcase.

The original torsion-bar rear suspension had been replaced by state-of-the-art shocks which had adjustable air-assisted damping — very advanced for the day. There were also experiments with twin magnetos.

Sadly, it would be a masterpiece Lambretta poured three years of development into for no return. The race effort never took off, despite enlisting GP’s first 125cc world champion, Cirillo “Nello” Pagani as test rider.

Another leading Italian rider, Romolo Ferri, had just two race outings on it, in France and Switzerland, but didn’t get anywhere near the podium in either Grand Prix.

A NEW BEGINNING

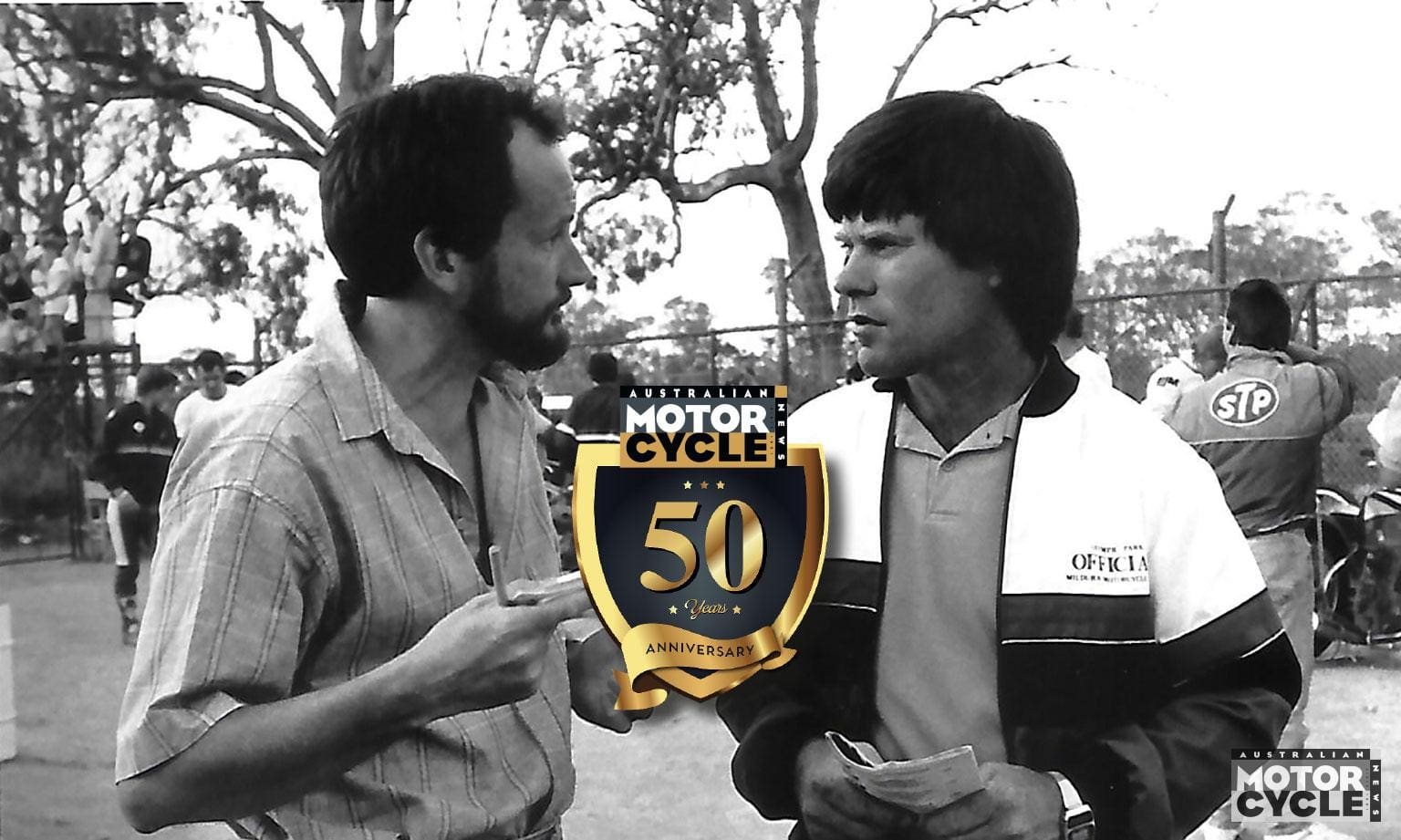

Abandoned and forgotten in a corner of the Lambretta factory, no one knew the Grand Prix bike still existed until Vittorio Tessera (pictured, right) came along in the late 1980s. A long-time Lambretta enthusiast who had become a guardian of the now-bankrupt company’s heritage, he gained the trust and respect of the Innocenti family. Eventually they gave him the archival remains of the factory, including a strange-looking four- stroke racer hidden under a dusty blanket.

“The bike was in very dirty condition, but complete and in the same state as when it had last run,” Vittorio said. “I understand there were two of these GP bikes made, but I have never seen them together in a photograph.”

His archive of factory photos contains an image of the race team’s ultra-clean workshop. It shows two complete engines on work stands and shelves of spare parts. One engine appears to be a SOHC version and the other the later DOHC version. Intriguingly there are three bike ramps in this room, suggesting more than one complete bike was built and raced.

Vittorio explains how although his racer was the last version, it is a mix and match of components from various years.

“It has the DOHC, wet-sump engine but is installed in the first frame built to accommodate the air-assisted twin rear shock absorbers,” he said. “The factory modified the racer step by step from 1951 to 1953.”

So maybe there was only ever one running, and one day he hopes to get this one going.

“I have problems with the camshaft but I hope in the future to solve this and start the engine again,” he grinned.

And that engine running through those open megaphones will be a moment to savour.

WORDS HAMISH COOPER

PHOTOGRAPHY PHIL AYNSLEY, VITTORIO TESSERA ARCHIVES