Change and decay in all around is what we are told to expect. But has racing got worse in 75 years? For better or worse? Not obviously. Certainly not in financial success, public appeal, social stature, safety and self – respect. And most certainly not in lap times. There aren’t direct comparisons to prove the point. Only one of the six circuits of the original 1949 World Championship remain basically unchanged, and that one, the Isle of Man TT, is no longer on the calendar.

All the same, plenty can be inferred from the speeds on the island. Fastest lap in 1949 went to Briton Bob Foster’s Moto Guzzi, at 89.71mph (144.37km/h). Peter Hickman’s current record stands at 135.452mph (217.998km/h). An increase of around 51 percent.

Here’s another way of looking at it. While the title-winning AJS was a twin and the Gilera runner-up an in-line four, the bulk of the field and even the 1951 title winner Geoff Duke rode single-cylinder 500cc Nortons. With some 54 horsepower (40kW), they were bikes for big boys.

There are still singles in the world championship, but half the size at 250cc. But with around 44kW they are more powerful, and at 82.5kg they are almost 60kg lighter. So assuredly a great deal faster.

But in the new century, these are bikes for beardless boys. Moto3 bikes, meant for mere beginners in their early teens. Marking human as well as technical progress.

Talking of humanity, here is the biggest change for the better. At the start of the series and for the next 30 years, the riders – all except for a handful of big stars – were treated much like performing animals, though without the regular feeding times.

For many it was hand-to-mouth; sleeping in tents or under the van, racing every weekend for prize money to support the grand prix habit. With no safety net should you suffer mechanical problems or injury.

In the 1950s reigning champion Duke was among leading lights who supported a strike for better start money. Suspension of his licence cost him the chance of a fourth consecutive 500 title with Gilera (he’d already won one with Norton). This typified the high-handed management of the sport, run for the benefit of promoters and circuit owners.

It took until the 1980s for this to change, when the abortive independent World Series, promoted by Kenny Roberts, forced the FIM’s hand. Rates of pay were immediately increased and it had set in motion the formation of IRTA and the establishment of a financial system that turned racing into a viable business proposition.

A good thing, obviously; but it is a bad thing that now, some 40 years later, riders in the smaller classes are having to pay for their rides by bringing sponsorship; while there are too many stories of unpaid mechanics…

The next big management change came when the FIM sold the series’ commercial and TV rights to Spanish company Dorna in 1991, after some serious manoeuvring.

It has generally been massively beneficial, and not only to the pockets of Dorna’s investors and management.

The rationalisation of TV rights is, for fans worldwide, the single most significant development. A very good thing, and getting better with the technical improvements in filming. But for many fans this led to a bad thing, as MotoGP TV is now increasingly behind a paywall almost everywhere in the world.

Many changes for the better. But what has got worse?

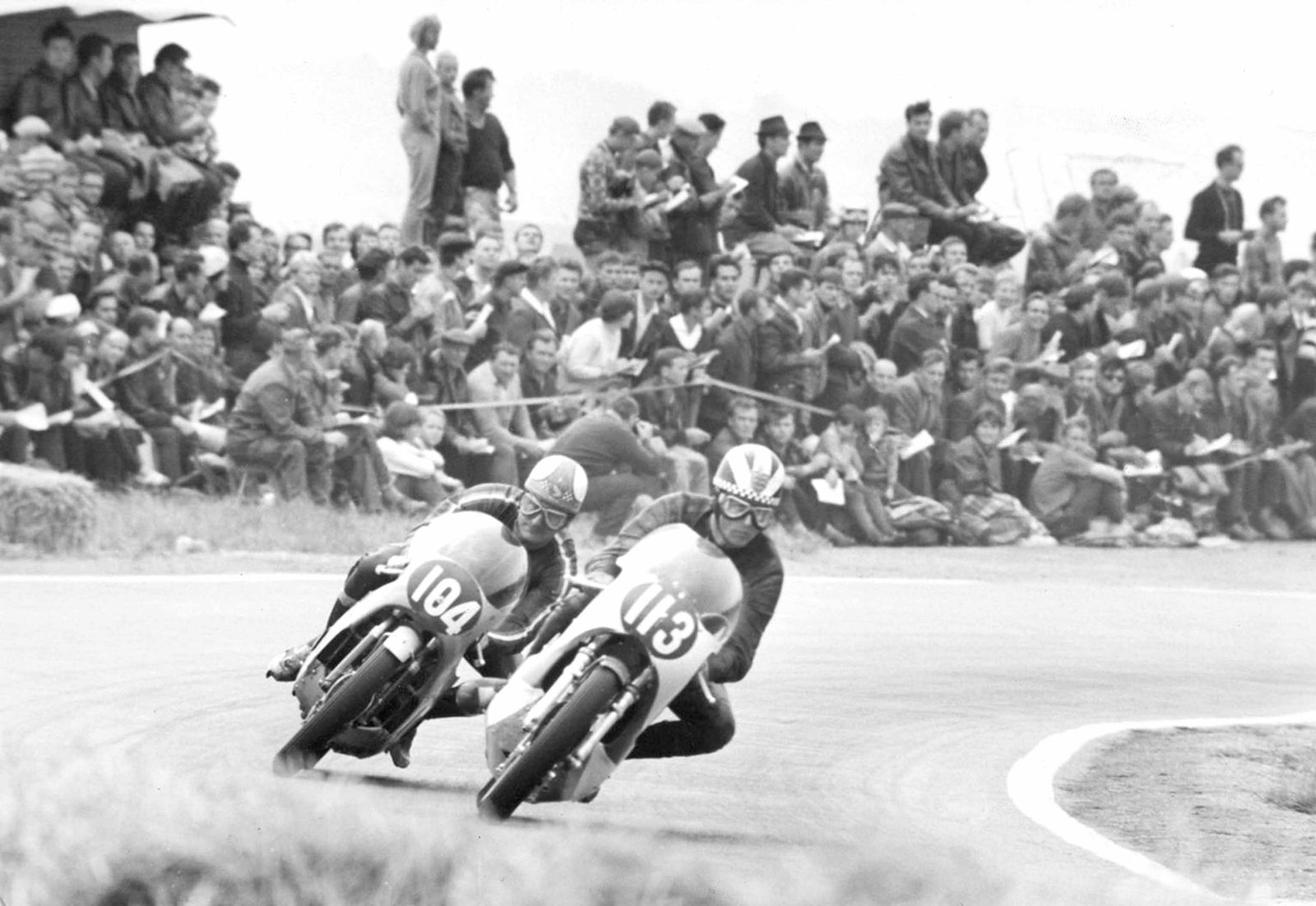

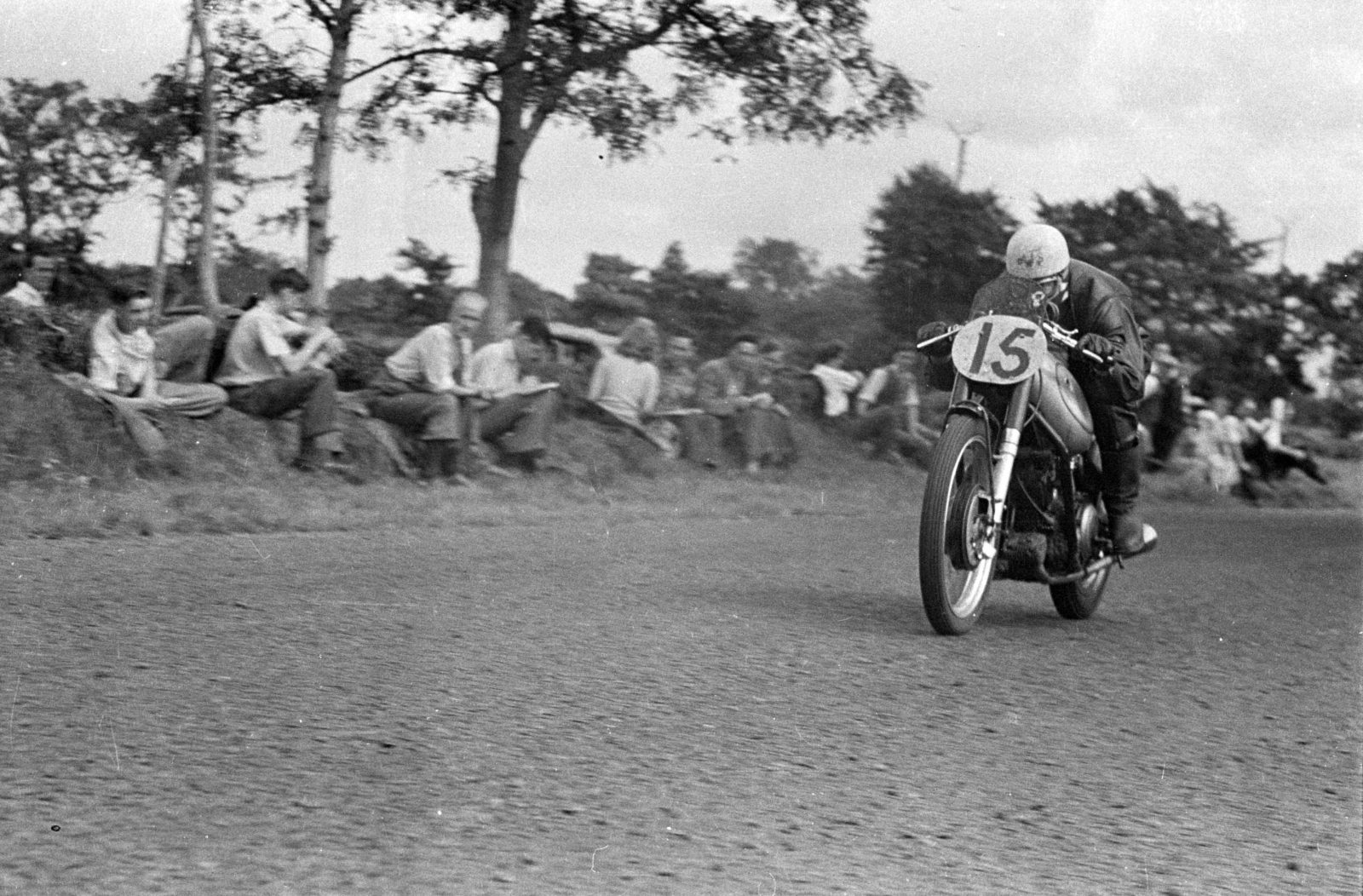

To pick one, accessibility. Crowd control. Look at the pictures from history… you see spectators (many wearing ties) right by the trackside. Close, and thrilling.

With a press pass, it is nowadays possible to get as close as this in some places… usually on the pit wall. Trust me, this proximity to a MotoGP bike at full throttle is visceral. More than breathtaking. But ordinary fans, on the far side of gravel traps and wide run-offs, can only imagine it.

Likewise paddock access. Once one could wander round at will, even into pitlane if you were pushy enough. Now a handful of big-pay ticket-holders get a carefully marshalled pit walk when there isn’t actually anything happening; while the paddock action takes place behind the swishing automatic doors of hospitality suites. The great unwashed are at more than arm’s length. Even if they wear a tie. On the plus side, no spectators have been injured by crashing bikes in living memory. So count your blessings.

Another down side is another type of accessibility – for independent engineers. There have been many over the years in the smaller classes and several in the premier class. Especially chassis designers, where the French have a special taste for wacky suspension.

Several Elf racers of the 1980s had double leading-link and later Macpherson strut front ends. Anyone remember the Fior, with a wishbone/girder combination? Or the Offenstadt, also French, with a trellis frame projecting enormous cantilevered forks with trailing-links?

The real adventurers made their own engines. The most notable have been relatively recent… like the short-lived Ilmor MotoGP four-stroke of 2005. From a successful F1 outfit, it failed to cater for a motorcycle’s different power requirements, and failed to find sponsorship.

Before them, Kenny Roberts had a serious go, building three generations of three-cylinder Modenas/Protons. The final Proton, elegant and refined, set the last two-stroke lap record at Phillip Island, ridden by Jeremy McWilliams. He started from pole… but by then MotoGP four-strokes had arrived and their extra muscle rendered this beautiful and independent racing bike redundant. Roberts persisted with a V5 four-stroke, but the cost and complexity of the extra technology eventually defeated him.

There remains one shining example, and a worthy memorial to the late Kiwi racer who mounted a serious challenge to the MV Agusta domination, before the arrival of the game-changing Yamaha. Kim Newcombe saw the potential in the Konig, a flat-four two-stroke hydroplane engine, and he turned it into a successful 500cc racer. His greatest achievement was to win the 1973 Yugoslav GP, among six podiums over two years. Sadly, he was fatally injured later that year but was still second to Agostini in the championship.

One last celebration of unorthodoxy was Honda’s attempt to turn back the tide of the two-stroke takeover. The NR500 of 1979-1981 was pig-headed but marvellous – unconventional in every aspect, including oval pistons with eight valves per cylinder, an upside down fork and monocoque bodywork where the fairing doubled as the chassis. If only the two-strokes hadn’t been better in every respect.

No pioneers left, sadly, except in the arcane details of electronics. And aerodynamics.

When it all began, rudimentary fly-screens were optional. The first big breakthrough came from 1951 champion Duke, replacing flapping two-piece riding suits with skin-tight one-piece leathers.

It wasn’t all primitive, however; particularly in the smaller classes, where 1950s experiments with fairings included the extraordinary beak-nosed NSU 250 Rennmax.

Moto Guzzi had its own wind tunnel to develop elegant full-cover dustbin fairings. These might have offered important advantages for future road motorcycles, which have always imitated racing fashions, but sadly the science was quashed by FIM regulations in 1958, entrenching the dolphin fairing, with all its modern manga variations.

There was a good reason. While factory bikes had sturdy framework and tail fairings that balanced the centre of air pressure, low-budget imitations lacked these refinements. They were dangerous not only in side winds, but because they might fall to pieces.

So a good thing for safety; but bad for a potentially quite different modern motorcycle.

Recently, motorcycle aerodynamics have embraced a whole new level – thanks especially to Ducati, seeking marginal advantages in the most regs-restricted era so far. With power to play with, the Dukes sprouted a profusion of winglets and ducts – on the fairing nose and flanks, under the swingarm and on the seat back. The rivals first protested, then imitated, then innovated themselves: hence Aprilia’s ground-effect fairing-flank bulges, and scoops and winglets on swingarm and front hubs.

Good? Not according to Marc Marquez, who sums up a widespread dissatisfaction. The new aero takes the lion’s share of blame for the fact that overtaking has become increasingly difficult. A slipstream of dirty air means your own aero, meant to cut wheelies and improving braking grip and stability, doesn’t work. So you have to drop back again.

The 75 years of GP can be divided into five broad categories of change.

In the Classic years, 1949 to 1960, bikes were clear descendants of their prewar counterparts. The relevance to real-world motorcycling was direct, give or take a few cylinders. Costs were ever-rising, however, while motorcycle sales were flagging in the face of cheap small cars. By mutual agreement the Italian factories pulled out at the end of 1957 only for MV Agusta to break ranks, and stay on for a long and sterile spell of domination.

This proved to be a bad outcome for it was stultifying for the premier class.

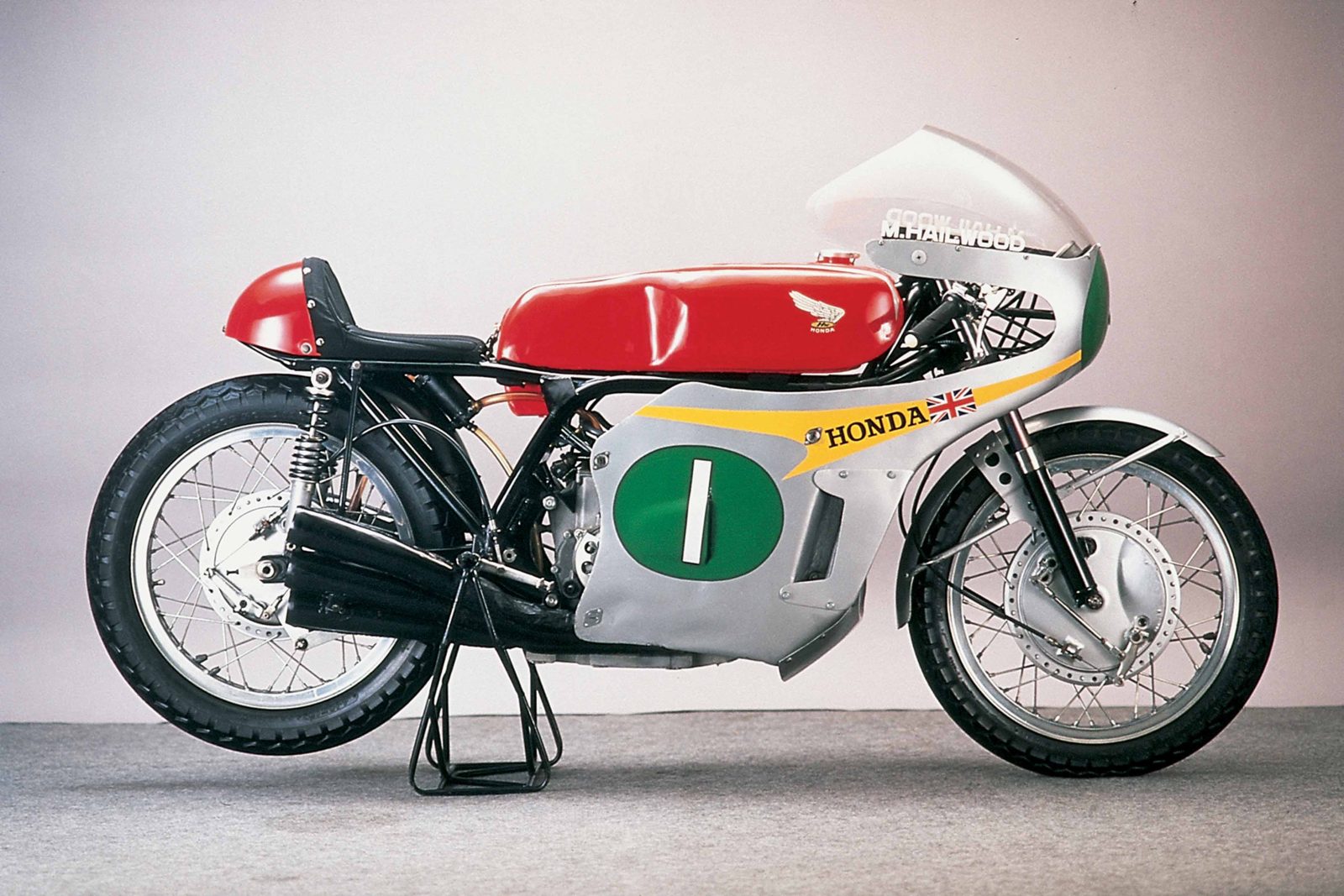

Then, the Mad years. Burgeoning Japanese industry powered a profusion of mechanical complexity – multi-cylinder four-strokes fighting multi-gear two-strokes. Honda’s five-cylinder 125 and six-cylinder 250 were unforgettable four-stroke high points; up against them square-four and V4 two-strokes from Suzuki and Yamaha. Suzuki’s title-winning 50cc twin of 1967 had the most gears, with German rider Hans Georg Anscheidt kept busy hunting for a narrow power band with 14 ratios to choose from.

It was, in all classes except MV’s 500 class, brilliant. But sadly unsustainable. Which was a bad thing.

FIM rules again applied stringent limits to the numbers of cylinders and gears. It drove the Japanese factories out, much to the relief of their accountants. In fact, financially beleaguered Honda had already decided to quit.

Then, the Budget years, when Yamaha found a new market for simplified racing motorcycles: the TD and water-cooled TZ 250/350 series, with much in common with production bikes. Except no headlights. It was a privateer’s heaven. Good for them and for brilliant close racing, if not exactly a technical golden age.

Era number four is a fading memory. The Two-Stroke years were ushered in by the return at factory level of Yamaha in 1973, with the four-cylinder 500. Jarno Saarinen won the first two GPs, retired from the third, but was killed in the fourth. Yamaha pulled out of the premier class and left MV Agusta to two more swan-song seasons.

Yamaha breached the wall in 1975 with former MV stalwart Giacomo Agostini. There was no going back, but there was a coming back from Suzuki, whose new square-four RG500 revived an earlier Mad-years 250 configuration. Then Honda also returned with their own two-stroke, winning their first 500cc title with Freddie Spencer in 1983. That was with a nimble triple. By the end of the era Honda’s V4 NSR had become the definitive two-stroke racer.

Two-strokes were definitely a good thing: light and powerful, they remain to many the best racing motorcycles of all time. But 22 years of development mean that their four-stroke MotoGP replacements, denizens of the fifth Modern era, are also a good thing. You can’t stand in the way of progress.

We are now on the third generation of MotoGP, the first-generation 990s supplanted by the unloved 800s (definitely a bad thing) and then by a return to 1000cc. Electronics, aerodynamics and creative thinking in chassis behaviour, namely ride-height adjustments for different circumstances, are among a program of general advancements that sees lap times falling and top speeds rising, in spite of restrictive regs decreeing four-cylinder engines with an 81mm maximum bore size, among other restrictions.

Good or bad? Impossible to say. But it’s sad that hidebound grand prix racing nowadays has little relevance to street motorcycles, more electronically advanced than their hog-tied racing counterparts. And that by banning such variations as dustbin fairings and feet-forward designs an area of worthwhile experimentation has been quashed. Then again, the view from the sofa on Sunday evenings is better than ever. And that is the best good thing of all.

RUBBER SOUL

Massive changes to one single component had a profound effect on racing. In 1949, front tyres were ribbed and rear tyres had a block tread. For impecunious privateers a single set might last half the season. Maybe longer.

In 2024 each rider is allocated 22 dry tyres per race – 10 front and 12 rear, in soft, medium and hard compound ranges; frequently with different compounds on each side. Plus wet tyres, if required.

Slicks arrived in the 1970s, a cross-over from drag racing pioneered by Goodyear. Unusable on a wet track, this introduced severe difficulties in changing conditions, eventually solved with mid-race bike swaps.

Later in the 1970s Michelin developed radials in racing, with a future use on the road.

The complications were bad, the developments good. Much better road tyres is the result. This is one area where racing really did improve the breed.

SAFETY (AT) LAST

For the first 16 years of the world championship, there was at least one fatality every year – in 1951 six riders died, in 1953 and 1964 there were five.

The annual toll resumed in 1966, with a peak in 1976 of seven – six on the Isle of Man, scene of the greatest number of fatalities. But even after the TT was dropped from the calendar after 1976, riders continued to die: 24 in the 1970s. This was cut to 13 the following decade, and to just two in the 1990s.

Safety considerations, mainly safer circuits with adequate run-off, air-fences and deleted barriers, and better rider gear (even before today’s air bags) had started to help.

This is the greatest advance in 75 years.

In 14 years since 2010 there have only been four deaths.

Worryingly, in the current era of ultra-close racing, all but one took place when riders were hit by other bikes.

WORDS: MICHAEL SCOTT PHOTOGRAPHY: GOLD&GOOSE & ARCHIVES