What happens when MotoGP tech meets monsoon-grade madness? Here’s a page-by-page analysis of how Ducati’s Panigale V4 S delivered a maelstrom masterclass

Today’s superbikes are awash with sophisticated electronics and rider aids – and none showcases the most advanced and fiendishly cunning systems better than Ducati’s 2025 Panigale V4 S. The technology on this, let’s not forget, road-going model have been developed, tested and proven by Casey Stoner, Valentino Rossi, Andrea Dovizioso and Pecco Bagnaia in MotoGP, and the likes of Alvaro Bautista in WorldSBK.

It’s easy to be dismissive and write off this direct connection with racing as marketing hyperbole, but ask Ducati’s highly regarded and straight-talking lead development rider, Alessandro Valia, how advanced the Panigale V4 S systems really are, and he says : “If we are talking about the DAVC (optional Race Pro software) suite (DTC, DWC, DSC), then we are at a level much higher than in MotoGP 10 years ago.”

Ducati aren’t messing about here. When the Bologna factory launched the 2025 V4 S at the Autodromo de Vallelunga circuit just north of Rome – with every intention of confirming Alessandro’s claim – we had a full day in the saddle to test every key rider aid installed on the machine and, back in our pit-box, assess the benefit it delivered to the rider via data analysis with Ducati’s top technicians.

There are five factory pre-set modes to choose from: Race A, Race B, Sport, Road and Wet. For each, the available and relevant rider aids and set-up of the Öhlin’s electronic suspension change and recalibrate automatically. Using the neat switchgear on the left handlebar and the beautiful and clear new TFT dash, you can simply move between the modes to match how and the way you ride. At a trackday you might start in Sport mode, then move to Race B as you learn the circuit. Perhaps towards the end of the day, when you are tiring and the tyres are losing grip, you can reduce the rider aids within those modes to compensate. Essentially you are trimming the bike to how and the way you ride.

The question is: how do we test and evaluate the kind of sophisticated tech that even helps MotoGP riders stay on the limit in the rain?

I’ve raced at a decent level on the roads and have 10 finishes at the Isle of Man TT, and a top 15 finish at Ireland’s North West 200. I’ve even road raced in New Zealand at Whanganui’s Cemetery Circuit but, sadly, I can’t powerslide a 216hp Ducati Panigale in third gear, especially one fitted with Pirelli slicks in perfect conditions. Big MotoGP powerslides that push the rider aids to the very limit? I don’t think so…

There is an answer, though. Test in the wet. With grip vastly reduced, it’s easier (if more dangerous) to reach even a Panigale V4’s limits. In theory, given some torrential rain, we could put Ducati’s rider aids properly under the microscope. Furthermore, Ducati agreed. All we needed now was some big black clouds.

Chasing the data

Conditions could not have been worse. Or, should I say, better. The rain was biblical, with lots of standing water and rivulets running laterally kerb to kerb – but at least the air temperature was in the low 20s. We fitted Pirelli full race wets plus a clear visor, then set about tailoring the Panigale’s rider aids for the conditions.

First, though, I felt compelled to ask my technician why we couldn’t just select Wet mode and go have a splash round with 160hp instead of 216. The answer lay with the preheated wets, which need to be pushed hard from pitlane in order to maintain that heat. If you start steadily, tyre temperature can drop, lowering grip levels that can’t easily be retrieved. Wet mode is designed for the road, meaning we wouldn’t have enough power to generate the required heat, while the rider aids, including cornering ABS, would be too intrusive, and the active Öhlins suspension would be too soft. Wet mode is more of a get-you-home setting rather than a performance option.

With this in mind, we opted for a bespoke set-up and much more of a conventional track setting. Power was set to Medium (not Low, as you might expect), which gives full torque in the higher gears. Compared to the conventional Wet mode, DTC was at intervention level 7, not 8; DWC was at 3 not 6; EBC remained the same as Wet mode on 3; and ABS was set to 3 instead of 7. The third generation Smart EC3.0 Öhlins suspension was put into a bespoke Active Track 4 setting. So, apart from DSC, which remained at Wet mode’s level 2, a very different set-up from the standard Wet mode.

Heading out onto an empty track on a brand-new Panigale V4 S in treacherously wet conditions was a strange feeling. I knew I had to put the hammer down, yet my every instinct was to have a good look at the circuit first. So, after a quick look over my shoulder as I entered the track, it was head down behind the screen, a tap on the perfectly slick race-shift gear selector, and feed in those angry Italian horses. Here we go!

Immediately, rainwater runs from the screen and sculpted bodywork as I take Turn 1 and 2 in fourth gear (normally fifth into sixth in the dry). Into Turn 4, it’s heavy on the ABS-assisted brakes, keeping that precious heat in the front Pirelli, while trying to be smooth. Exiting Turn 5 into 6, it’s hard on the gas and time to be brave.

I’ve only done 30 per cent of the lap but can already feel the rider aids working. TC and slide control are working overtime as I feed nearly 220bhp onto the Pirelli. The system is sublimely smooth – no bangs or misfires – but clearly holding me back as it meters the flow of power and torque.

The final section of track from Turn 8 is tight and technical, the opposite of the rapid first section. In this section you still rely heavily on the rider aids, but also chassis feel, with kneesliders desperately seeking the Italian racetrack.

Like a normal trackday, session one is all about finding your feet, evaluating where the grip is, which kerbs can be clipped and which can’t. The wet conditions are forever changing as the rain gets heavier then briefly relents, and sometimes a wider line has more grip than the conventional line. After several laps without blinking, it’s time to head back to the pits to check out the data.

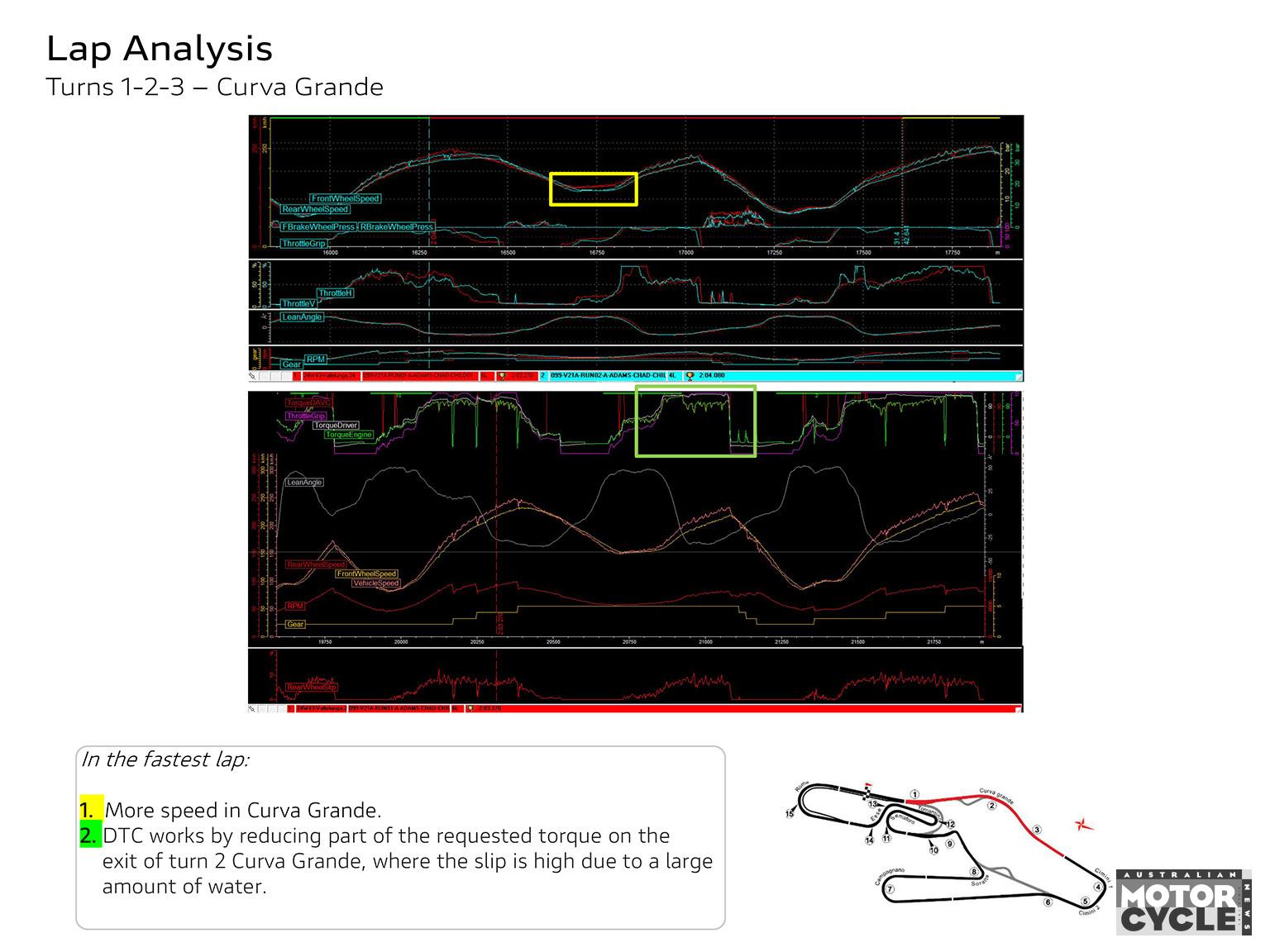

Good data takes no prisoners but can also be extremely illuminating. The traces on Page 2 of my Lap Analysis report show that as I gain in confidence I’m getting faster and faster through turns 1, 2 and 3, the scary-quick Curva Grande. The three lines in the yellow box show my apex speed is higher. As the line rises after the yellow box, you can see I’m carrying more speed around the long Turn 3 before breaking for Turn 4 at close to 240km/h.

But what is making me quicker in this section isn’t bravery, it’s those predictive rider aids. Take a detailed look at the highlighted green box on the same page of the report: the throttle position is the purple line, which is almost 100 per cent open. The amount of torque I’m requesting (white line) is also nearly 100 per cent and matching the throttle. But the green line, which is actual engine torque fed to the back wheel, is way below the purple and white lines in terms of percentage of maximum. I’m in fifth gear with 100 per cent throttle, asking for 100 per cent torque, but the Ducati is giving me only as much torque as the system deems necessary to keep me safe.

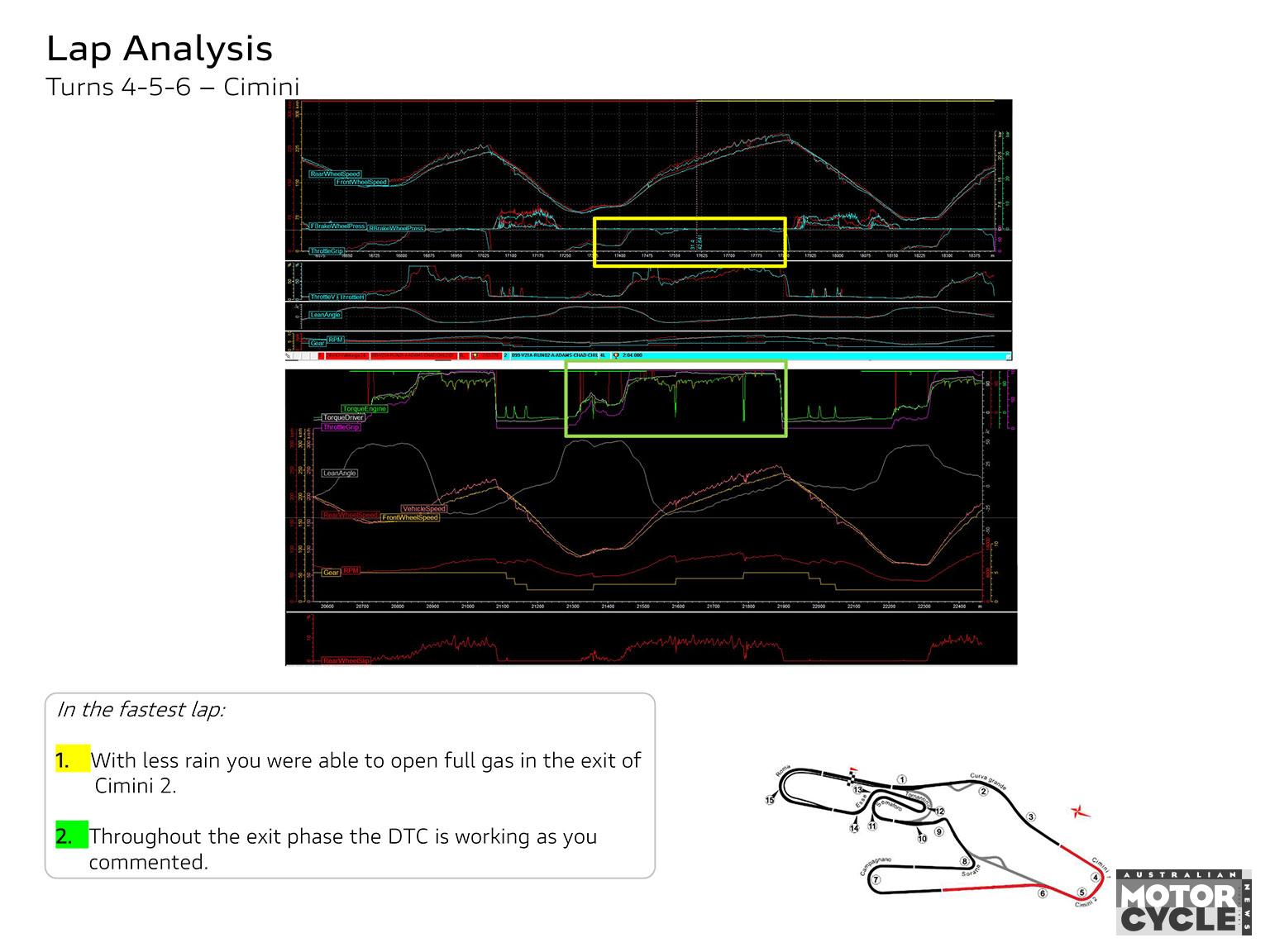

Same again in Turns 4-5-6, called Cimini. In the highlighted yellow box (Page 3) we are comparing two lap times: the red line’s 2.03.22 and the blue line’s 2.04.08. The faster lap (red line) shows I’m getting on the power sooner and going to 100 per cent throttle on the exit.

But, again, it’s the rider aids doing all the work. The highlighted green box shows 100 per cent throttle (purple line), that the torque request nearly matches the throttle (white line) but the torque going to the back tyre (green line) is much less. The large spikes you see in the green actual-torque line are the rapid quickshifter upshifts.

In this section I start accelerating at around 95km/h, aggressively opening the throttle to 100 per cent (purple line), upshift and accelerate hard all the way to 250km/h. I’m using third, fourth and fifth gear and 100 per cent throttle, but the traction control (DTC) is limiting the actual torque to the wheel because the wheel is spinning (bottom red line, which shows rear wheel slip).

Despite the horrendous conditions, I’m purposely riding like an idiot: going to 100 per cent throttle and asking for 100 per cent torque, but as the green line clearly shows, the Panigale will only give me a limited amount of precisely controlled torque. Otherwise I’d simply lose the rear.

Page 4 shows what happens when you nearly get it wrong. We are still in the Turn 4-5-6 Cimini section, but this time driving through Turn 6. Again, I’m at nearly 100 per cent throttle (purple trace) and asking for almost 100 per cent of torque, while the actual torque supplied to the rear wet is much less. But now the conditions have worsened, there’s even more rain, and the rear is sliding with 2.5 degrees of yaw, meaning the back wheel is no longer in line with the front. Front-wheel speed is consistent but the rear-wheel speed is not – and the yaw line shows the slide.

On one occasion I got a little too carried away with 28 degrees of lean angle and the system saved the slide in 0.06 of a second, way before I could. I physically still reacted to the slide, closing the throttle, but the system had intervened first.

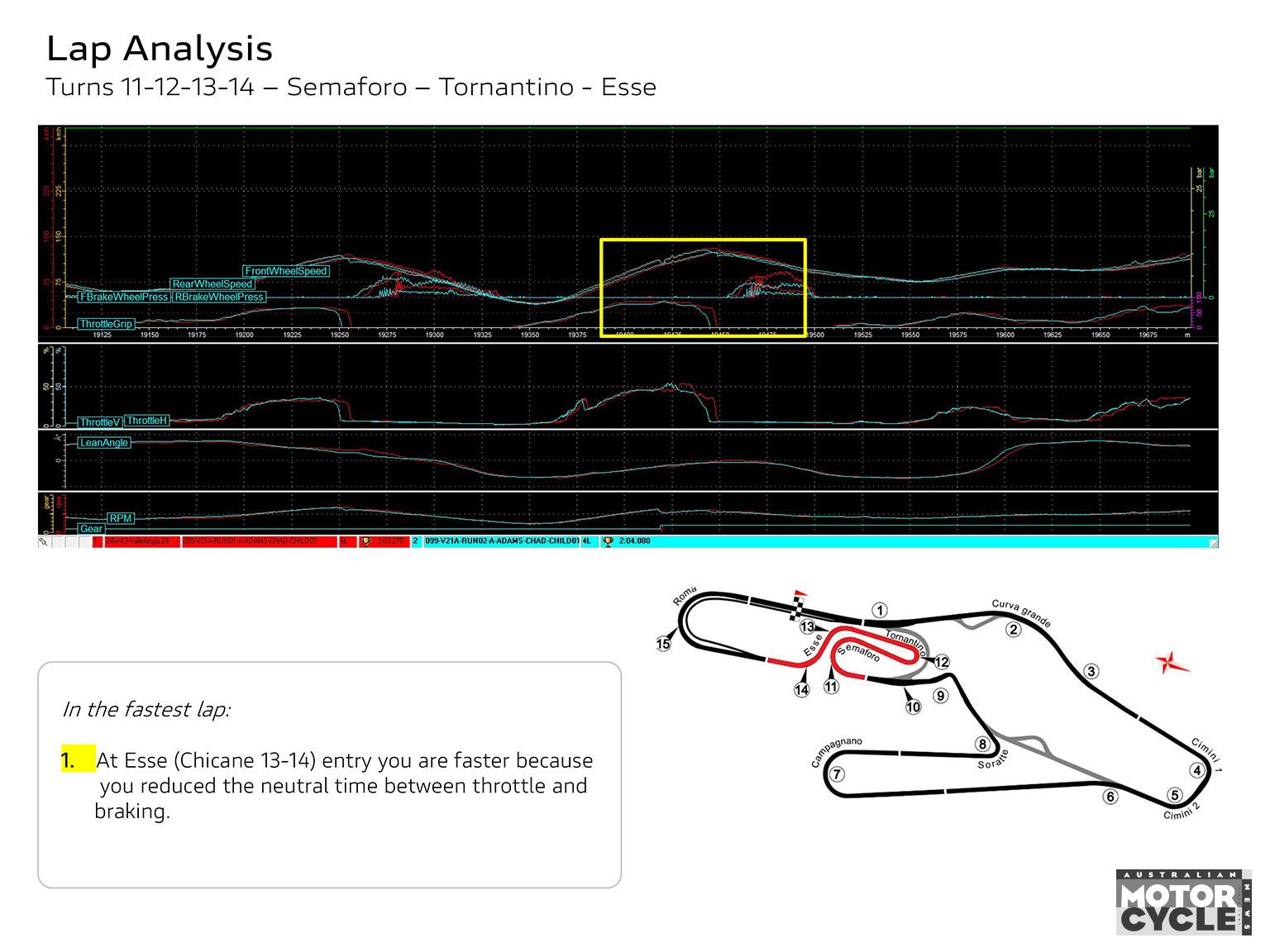

We didn’t try the most extreme and race-focused eCBS, the new linked braking system that activates a percentage of rear brake when the front lever is squeezed and trails the rear brake up to the apex, even after you have released the front. But we did set the cornering eCBS to level 3, which is designed to be used on a track. The front applies the rear automatically and we can see this working in the data on Page 6.

The throttle grip (purple line) goes from fully open to closed, and the brakes are applied. I’m only braking with the front brake. In the highlighted green and yellow boxes, the top blue line is the amount of brake pressure I’m applying, while the actual brake pressure being applied by the cornering ABS is the green line underneath – this prevents the front from locking. The white line is rear brake pressure – remember, I’m only applying the front brake, the system is doing this automatically. ABS is also working on the rear, which is also being applied automatically.

The bar chart in the top right (Page 6) shows this in actual figures. I’m applying zero bar of rear brake pressure, but the system is applying 3.8 bar of rear brake pressure, which is obviously reducing my braking distance, making the bike more stable and giving the front brake and tyre an easier time. I didn’t touch the rear pedal on any occasion, but the eCBS system repeatedly applied the rear – and we can see this throughout the data over the entire lap.

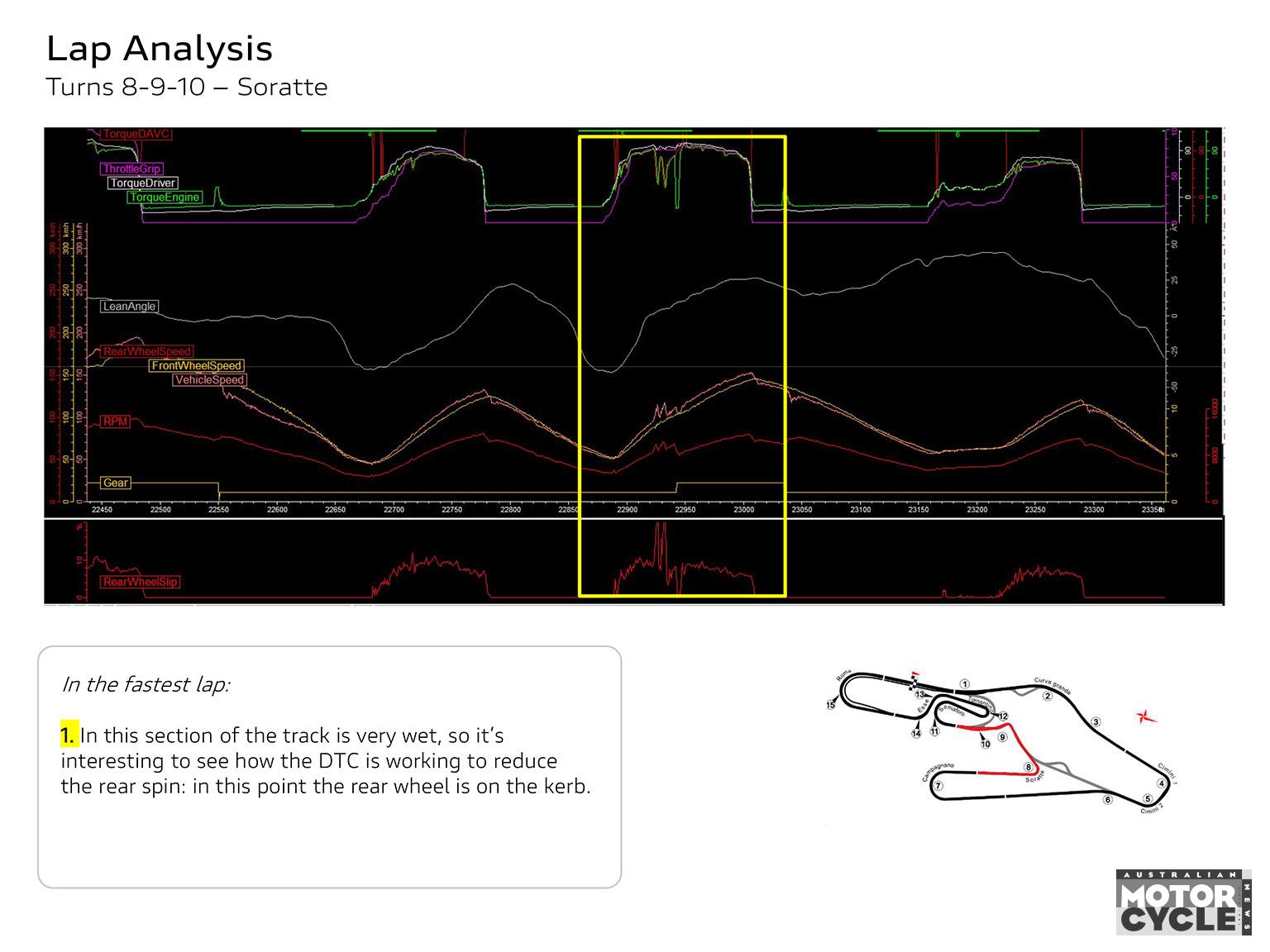

On the exit of Turn 9 you can run your tyres over the inside kerb, which today is obviously very slippery. It took a while to build up to this, but I wanted to see how the system would operate with a dramatic loss of grip while riding over the kerb. Again, throttle position and torque request are high (purple and white lines respectively) but as soon as the rear wheel touches the wet kerb, the rpm peaks, rear wheel speed peaks and rear slip goes crazy. There’s a dramatic spike in the traces. But, almost simultaneously, the DTC reduces actual torque to minimise the wheelspin – that’s the green line below throttle grip (purple) and requested torque request (white). Once the Panigale’s rear wheel is beyond the kerb, the rpm are restored and torque is reintroduced.

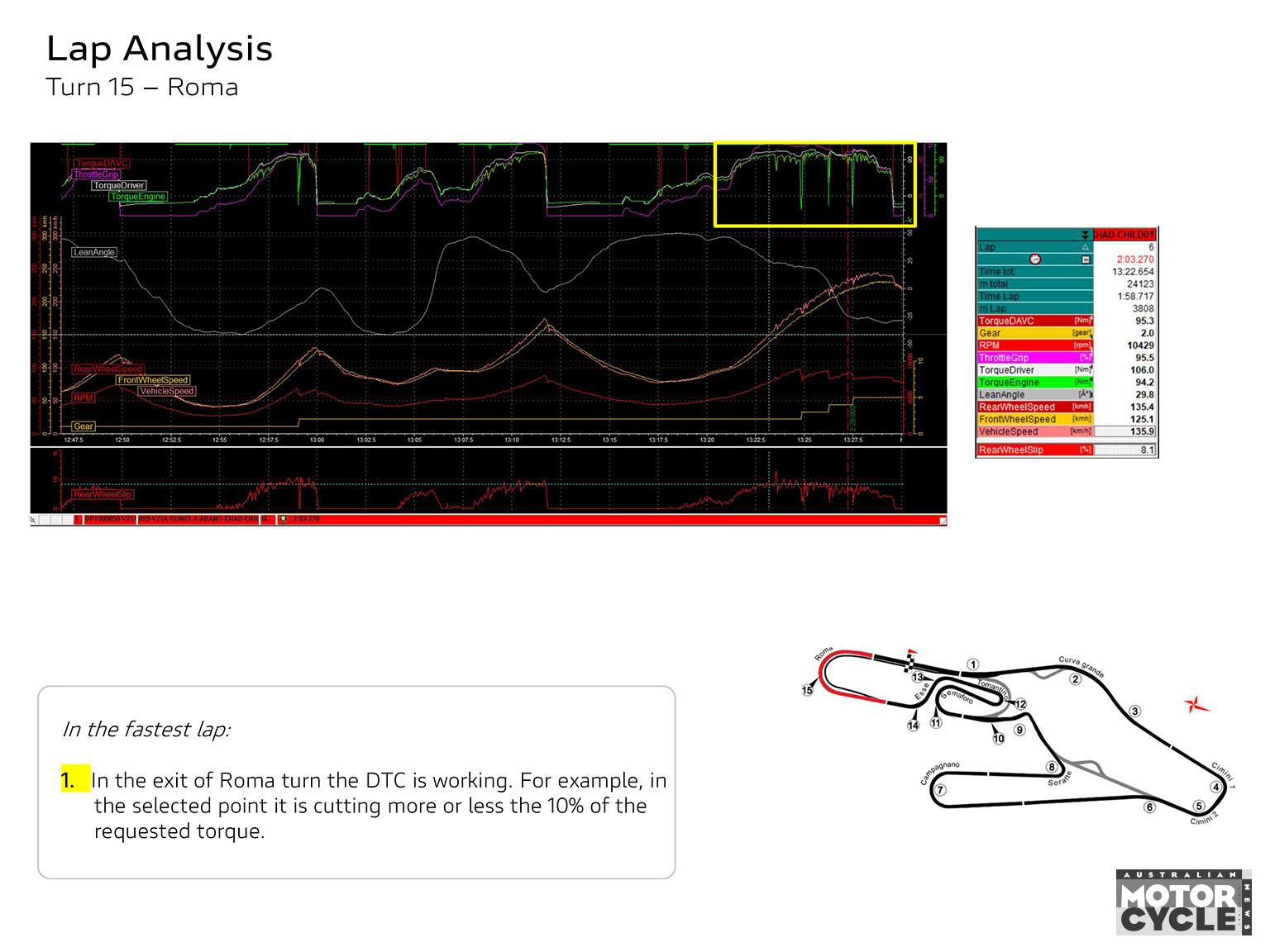

Finally, the exit of Turn 15, Roma, onto the start/finish is particularly tricky, especially in the wet. You’re accelerating towards the finish line but still banked over in a relatively low gear. Each lap I forced myself to accelerate earlier, striving to get to full throttle with the bike still leant (and putting all my faith in the genius of Ducati’s electronic engineers).

The highlighted yellow box on Page 9 shows the wide opening of the throttle (purple line) with the actual torque going to the rear wheel much lower (green line). The V4 S is in second gear, the engine is at 10,429rpm, the throttle position is 95.5 per cent open and the chassis is at 29.8 degrees of lean.

I’m trying to accelerate hard, with lean, in the wet – not the brightest idea. I’m requesting 106Nm of torque but what is actually going to the rear wheel is 94.2Nm or 10 per cent less than I’m requesting. We can see the slide on the graph (red line) and the data shows the front wheel at 125.1km/h and the rear wheel at 135.9km/h. You can see that I’m riding like a fool but you can see how the bike is making me look like a hero.

Verdict

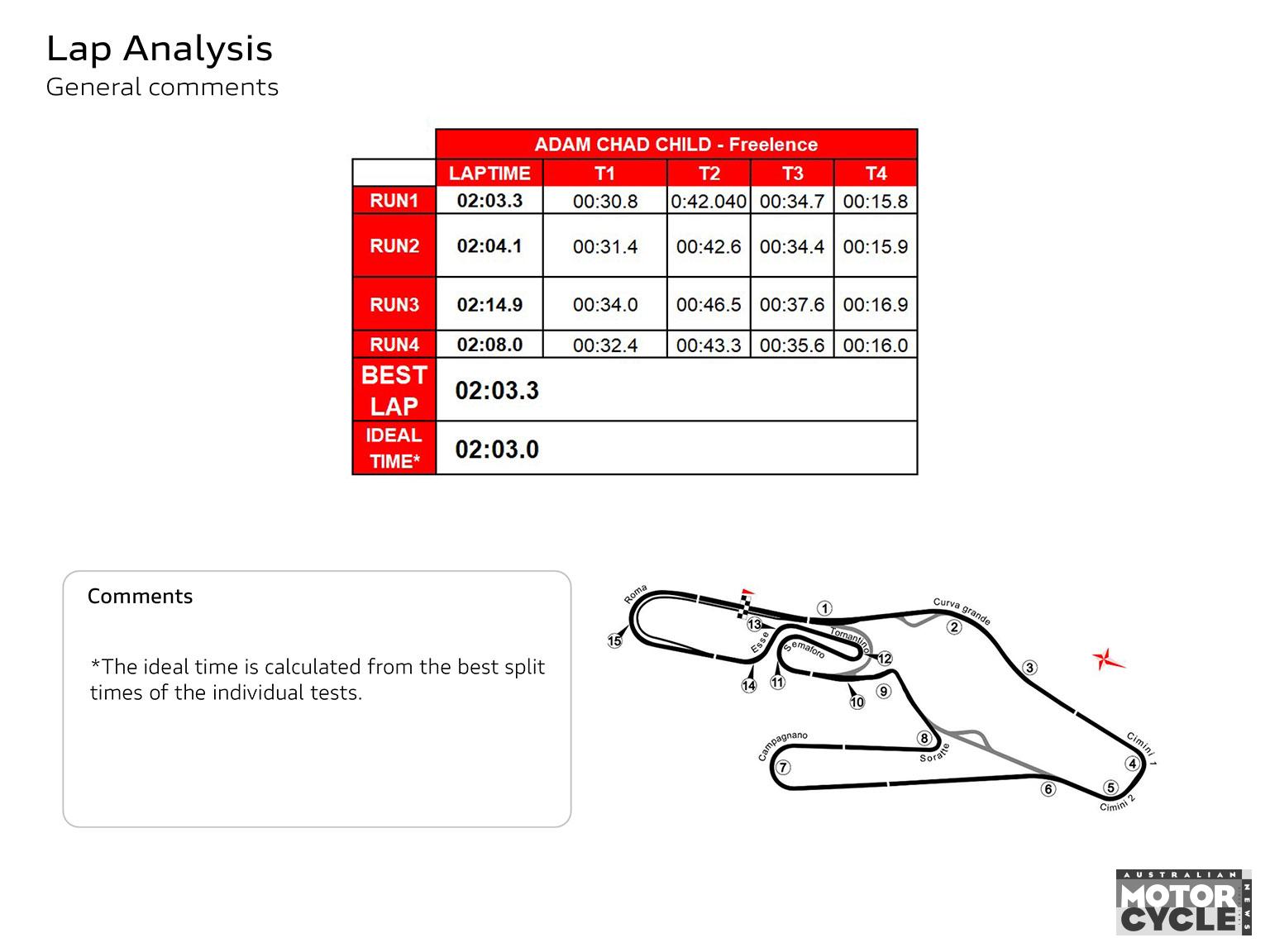

There will always be an argument for and against rider aids. The latest are designed to make riding on the road and track safer, easier and, should you wish, faster. My best lap time in the wet during this test was a 2.03 (my PB in the dry is 1.45), which shows how bad the conditions were. Typically, I’m around 10 to 12 seconds slower in the wet depending on the track. But without the Ducati rider aids working in the background, I’d estimate that my best time would have been 2.05 or 2.06, while achieving those times would have required draining amounts of 100 per cent concentration.

With such a complete and integrated network of riding modes and rider aids I could relax, knowing I had this priceless safety net. I knew I could go to 100 per cent throttle and it would save me. I knew I could jump on the brakes and that the cornering ABS would keep me upright and on line. The laws of physics still apply: you can still lose the front off the brakes, the rear can wash out, and you have to concentrate – but you don’t have to be a pro racer to have fun in the most difficult conditions.

The average trackday enthusiast can reach new heights. Finessing your bike’s set-up has never been easier, quicker or more rewarding. At a wet circuit, turn all the rider aids to max, feel them working, then come back a little, until you’re comfortable.

I’m truly amazed by Ducati’s latest electronic technology: to see the data and what is happening was an eye opener as it’s all too easy to jump off a modern superbike convinced that a hot lap-time is all your own work. Clearly, our Panigale was keeping its rider out of the gravel.

Alessandro Valia is right: we really do have better rider aids than Rossi and Stoner ever had on their MotoGP Ducatis. Think about that!

Alessandro Valia, Ducati development rider

How advanced are the rider aids on the latest Panigale?

“IF WE TALK about the DAVC suite (optional race pro software) (DTC, DWC, DSC) we are much better than a MotoGP of 10 years ago. The new generation of controls, based on the DVO (Ducati vehicle observer), is not anymore based on wheel speed and lean angle, but on the forces that impact the vehicle and the centre of gravity positioning in every riding phase. Basically, we don’t wait for the slip or wheelie to manifest in order to intervene, but we know in advance the thrust that the vehicle can bear in every situation. This allows us to be much more accurate in the wheelie and

traction thresholds and targets definition, thus rendering the control predictive.

“The Race eCBS situation is completely different. The production bike is even ahead of our MotoGP and Superbikes, because ABS systems are not allowed in those championships. With this revolutionary system we are able to control the dynamic of the vehicle during braking and entry phases, improving the efficiency of the brakes and bike stability, thus moving forward the braking reference points. Last but not least, this new system is useful both for amateur riders who now have access to a higher riding level – this is the reason why we call it Skill Booster – and for pro riders who don’t need to think about rear brake but can focus on other riding aspects.”

How long did it take you to develop the rider aids on the 2025 Panigale?

“It’s been a long journey, from the first idea to transfer the MotoGP technology to the production bike, to the start of production. All in all, the process has taken about three years.

We started with a very big instrumentation mounted on the bike. It was quite heavy, with experimental software and all the 70 objective sensors on the bike. The most difficult thing was to create the algorithm that interprets all these parameters and fit everything in a small black box compatible with mass production.”

Which is more important: rider feedback or clever engineers and their algorithmic simulations?

“On one hand, it’s crucial to have clever, motivated engineers; on the other, it’s impossible for them to work without fast, sensitive riders. But the most important thing is that they trust each other. I am a lucky tester because my engineers know exactly what it means to ride – even those who have never ridden a bike!”

What is your one best tip for riding in the wet?

“It’s difficult to suggest to an Englishman how to ride in the wet… It seems trivial but the secret is to be smooth in every manoeuvre, especially on load transfers.”