Patience. It’s a virtue for any racer. For some, it’s the patience to wait another lap to make a pass, or settle for second place this time. Every racer must find some patience in order to reach the top. But only in land speed racing is that patience sometimes measured in years.

For three long years, Mike Akatiff and his Top 1 Ack Attack team had been waiting to make a run on the Bonneville Salt Flats in their attempt to officially reach 400mph – a magical number, as well as a new world land-speed record. But for three years in a row the Utah locale was flooded, and the Speed Week event cancelled. With the salt at Bonneville in a steady state of decline, Akatiff and his team decided it was time to act.

Finding a better track for the record run was easy – Bolivia’s Salar de Uyuni, the world’s largest salt flat, was the obvious location. But what stood between getting the team and equipment to Uyuni, and twisting the throttle to 400mph was anything but simple…

World-class challenge

The idea to make a run at Salar de Uyuni had actually been on Akatiff’s mind since 2006, but it wasn’t until recently that a trip to the remote Bolivian Altiplano became a real possibility.

“They’ve done a lot of things that make it practical to go,” Akatiff says. “They have an international-size airport at Uyuni. There’s also a paved road from the capital, La Paz, all the way to Uyuni now. It looked pretty promising.”

With access sorted out, and scouts including Bonneville Speed Week promoter Mike Cook and South American land-speed racing enthusiast Andre Rodrigues working together on the legal and logistical elements in Bolivia, the Top of the World Land Speed Trial began to take shape.

Back in his shop in San Jose, California, Akatiff had his own set of challenges to face in preparation for Bolivia – namely the altitude. At 3600 metres above sea level, the conditions at the Salar de Uyuni are starkly different from those at Bonneville, which sits at 1200m. Significantly thinner air makes it harder to build power, but less air pressure makes it easier to cut through the atmosphere – a double-edged sword that would prove critical in the Ack Attack’s South American exploits.

A custom turbocharger from Garrett Turbos ensured the Ack Attack could suck enough air at the extreme altitude. “They designed us a new turbo with all solid machined wheels and it is absolutely able to make 30 to 40 pounds of boost up there no problem,” Akatiff explained.

Fluid dynamic calculations and the team’s work in the wind tunnel provided some promising figures, revealing that the Ack Attack would gain an eight per cent advantage in overall speed thanks to the lower air pressure.

“If you have so much power available and you go 400mph at Bonneville, and then go to Uyuni and run the same power and the same amount of drag, you’re all of a sudden going 432mph. That’s eight per cent faster.

“We have another trick up our sleeve. We’ve never actually set a record with a tail on the bike, but we think we have solved that. If we can run with the rear doors on, that’s another nine per cent – that’s another 30mph right there. So the same speed, the same power, the same wind resistance we had at Bonneville at 400, we would be over 450mph in Bolivia. Plus we have 10 miles, if we need it, to run up before we get to the trap.”

There were plenty of reasons to be optimistic heading into the Top of the World Land Speed Trial, but as land-speed racing has proven time and again, there is no predicting what will happen until you attempt it.

On top of the world

The reception from the country itself was nothing short of overwhelming. Under the leadership of president Evo Morales, Bolivia is pushing to be recognised on the world stage, be it through tourism, motorsports like the Dakar Rally, or the country’s effort to control the extraction of its own natural resources. These three elements come together in the Salar de Uyuni, and Morales is firm in his conviction that the salt flat is the key to his country’s future.

Hosting the first-ever world land-speed trial with film crews from around the world, including National Geographic, was therefore deemed worthy of the president’s presence. Friday 4 August (day two of the event) was dedicated to a festival on the salt at Mile 0, with music, dancing, food vendors and a presentation to celebrate the Top of the World Land Speed Trial.

“I was just speechless,” says Akatiff. “The number of dignitaries, the president of the country showed up. The tourism ministers were all there and it was just like… what is this? And thousands of people!”

Yet more stunning, and rather agonising, was the fact that the Ack Attack had yet to arrive. The first two days of the event had come and gone, and Akatiff had no confirmation that his container was even in the country yet. It was a complication they had not anticipated, and were powerless to fix.

“There was nothing we could do about it – it was out of our hands, and in the hands of the Chilean border people and the truck drivers. It was supposed to arrive, I heard three o’clock. But

I expected to see it about dark.”

A little after midnight, the team were relieved to finally hear a tractor-trailer rumbling down the dirt road toward the Palacio de Sal hotel. But it also meant the race was on – they had only three of the scheduled five days left on the salt to accomplish their goal.

On Saturday morning the countdown began. The team made attempts to start early, but limited daylight hours and sub-zero temperatures (winter in Bolivia!) made it difficult to get things thawed out and moving any earlier than 10am. There were also unexpected – and unexplained – complications to deal with before they could hit the track.

“The brakes worked fine when we left San Jose,”

Akatiff says. “We got to Uyuni and it had no brakes. And nobody touched the brakes – nobody did anything! And we had other odd things happen that we’d never seen before.”

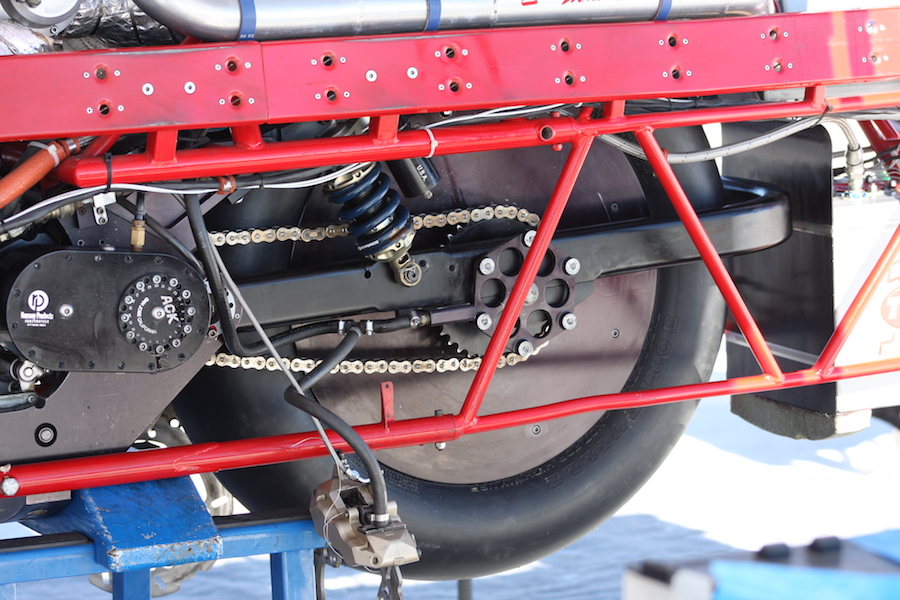

The team spent Saturday working through the brake issues (bleeding is complicated with three metres of brake lines) and also tuned the engine and went through FIM tech inspection.

Sunday morning the Ack Attack was finally ready to head to the starting line. Rider Rocky Robinson got things started with some shakedown runs to dial in the engine tuning, and ended the day with a respectable pass.

“We got up to about 358 top speed on the last pass,” Robinson says. “The bike ran a lot better; still not where it needed to be.”

Robinson had a slight issue at the end of the run when his landing gear (two small wheels that come out the sides of the streamliner) failed to work.

“I rode it all the way to the pits hoping someone would catch me, and they didn’t! I stopped right there and I just tipped over.” Not that catching a 900kg streamliner is a simple task. The small mishap resulted in some damage to the bodywork, but nothing that would stop the assault on the record.

Interestingly, the rear doors on the streamliner made a significant difference at speed, but seemed to make the Ack Attack too slippery through the air.

“I used up more course than I usually do using the doors,” Robinson says. “It was a little less stable so I was kind of all over the place. But I didn’t have any concerns about it because the traction on the salt was so good everywhere. Not used to that!”

Another slight learning curve came in the reading of wind conditions on the Salar. The wind report from the tower read at a steady six mph on Sunday afternoon – normally considered too windy for a run at speed. Except that the wind was barely perceptible and didn’t feel anywhere near six mph. FIM-authorised timing official James Rice figured out the anomaly, another effect of the altitude: “Because we were up at about 12,000 feet (3600 metres), we only got about two-thirds the atmosphere. So I did a quick calculation and showed that about a six-mph wind reading here was equivalent to a three-mph wind down at sea level.”

Saturday’s prep and Sunday’s shakedowns left the team ready for a full assault on Monday, the final day on the Salar. Hopes were high as Robinson got a push off the line and disappeared over the horizon with a white rooster tail of salt in his wake. But minutes later, hopes were dashed upon hearing the entry speed: 338 mph. Disappointment quickly turned to alarm as word then came that Robinson had blown past the pits and off the course.

Fortunately, the Ack Attack safely came to a stop, this time with the landing gear out. Robinson reported that he lost power about a mile before the timing lights and coasted through the trap. He intended to coast it into the pits (another seven miles) but with far less atmosphere to slow him down, he came in way too fast. Even the parachute did surprisingly little in the thin air. After blowing through the pits at Mile 0 and going off the groomed course onto the ‘popcorn’ salt, he was forced to cook the brakes to bring the Ack Attack to a stop.

The team’s hopes immediately sank as the assumption was made that one or both of the engines had blown, marking an end to their day. But upon removing the bodywork, it was discovered the problem was a turbo hose that had blown off the manifold. Everyone held their breath as Akatiff attempted to fire the engines to life again. At a flick of a switch, the Hayabusa engines both lit up, prompting cheers from the team.

“We went from 30 pounds of boost to zero boost at 12,000 feet,” Akatiff explained. “So we had no power. We were still in the game, which was the important part. And it was still early.”

The race was on to fix the roached brakes and get the Ack Attack to the start. The clock was winding down on the final day of competition, which has actually come to be somewhat of a signature of the Top 1 team.

“We’ve run it down to the wire twice and got the record,” Robinson says. “So you gotta roll the dice.”

The sun crept closer to the horizon as the Ack Attack got into position at Mile 15. This was it, the final effort.The same thought was on everyone’s mind: it just had to work.

Cook’s voice came over the radio, announcing that Rocky was off and running. Once again, a collective breath was held as the team awaited visual of the Ack Attack. It came into view of the tower at Mile 11… Mile 10… but just as Rocky entered the speed trap at Mile 8, the chute came out. Rocky had aborted the run.

It was over.

“I had a real good ball of steam going, and then about three or four miles into it I smelled something,” Robinson explains. “I didn’t know what it was and then all of a sudden it lost power just like the time before. We blew another rubber connector off the turbo.”

The turbo had let go again, this time in a different place. A fundamental problem then occurred to Akatiff.

“The difference is we’re at 20 inches of mercury here. And at sea level you’re at 15. Bonneville you’re about 18. That makes a lot of difference. You got all that boost and no atmospheric pressure outside. It’s just … nothing we would have thought about, you know?

“The next guy that tries this will learn from us.”

Hindsight

The Top of the World Land Speed Trial was a massive undertaking, for the team, the sponsors, the media and even the country itself. Without coming away with a record, what was it all worth?

“Well, we still have the record,” Top 1 Oil President Joe Ryan says with a laugh. “We can still say that.”

Although disappointment was shared in the pits, a sentiment that was not apparent at any level was regret. The Top of the World Land Speed Trial was a pioneering effort in every sense. The crew and fellow race teams worked their way through a trying week, and made history even if they didn’t set a record.

“What I’m impressed with in the land-speed community is that everybody is there to help each other,” Ryan said. “We’re in the middle of nowhere but you look at all the people here and they’re helping each other. To me, that’s part of life. You either are selfish or you work together. This team, this group is second to none in establishing that.”

As for what’s next for the Ack Attack, or for international land-speed racing in general, it might be too soon to tell. Will future world-record speed seekers need to consider Bolivia? Quite possibly. And will the Ack Attack return to Uyuni?

“I think it’s the end of the line for the Ack Attack,” Akatiff says. “I think for me, it’s probably pretty much the end of the line. But … never say never. We’ll see. We’ll go back home and talk about it.”

A quick recap…

The history of the Ack Attack stretches back to October 2002, when Mike Akatiff decided to start work building a land-speed racer with his friend Jim True. Two years later, in August 2004, the streamliner made its first runs on the salt. In September, while approaching 300 mph, rider Jimmy Odom came into a crosswind and wrecked the vehicle. Fortunately, Odom was not injured, and the team was able to prepare the Ack Attack for the Bonneville Nationals in October, where they ran a two-way average of 328.3 mph.

The world record at the time was 322mph, but the Bonneville Nationals was a club event, not FIM sanctioned.

In February 2006, the team traveled to Lake Gairdner, Australia, with the intention of setting a world record, but conditions were not good enough for speeds over 300mph. Fortunately Akatiff wouldn’t have to wait long before another opportunity came.

In September 2006 conditions at Bonneville were prime, and with new rider Rocky Robinson, the Ack Attack finally set a new world record at an FIM-sanctioned meet, reaching 342.8mph and smashing the old mark that had stood for 16 years. Celebrations were short-lived, however, as the Bub Lucky 7 streamliner reached 350mph the next day.

In September 2007, the Ack Attack returned to action but Robinson crashed at an estimated 320 mph. The streamliner rolled 16 times before coming to a stop. Fortunately, Robinson was not injured.

In September 2008 the Ack Attack was back on the offensive, and Rocky rode to a new world record at 360.9 mph. This time the team held the record for a year before the Bub Lucky 7 reclaimed the honour of fastest motorcycle in the world with a speed of 367mph.

In 2010, the Ack Attack team answered back yet again, claiming their third world record in four years, this time at 376.4mph. Robinson’s maximum recorded speed was 394mph, and the team got a taste of 400mph, which they claim to have reached after exiting the trap. Knowing it could be done, they now want to do it on the record, and be the first team to ‘officially’ break the 400 barrier.

WORDS & PHOTOGRAPHY JEAN TURNER