Words Peter Whitaker Photography PW & AMCN ARCHIVES

With the Jubilee Day parade commemorating 50 years of federation fast approaching, Alice Springs motorcycle enthusiasts saw an ideal opportunity and, on March 9 1951, formed the Alice Springs Motorcycle Touring Club. And to avoid throwing the small community into a tizz, declared the club had no intention of engaging in speed races. Theirs was to be a purely social club for arranging tours, picnics and family outings.

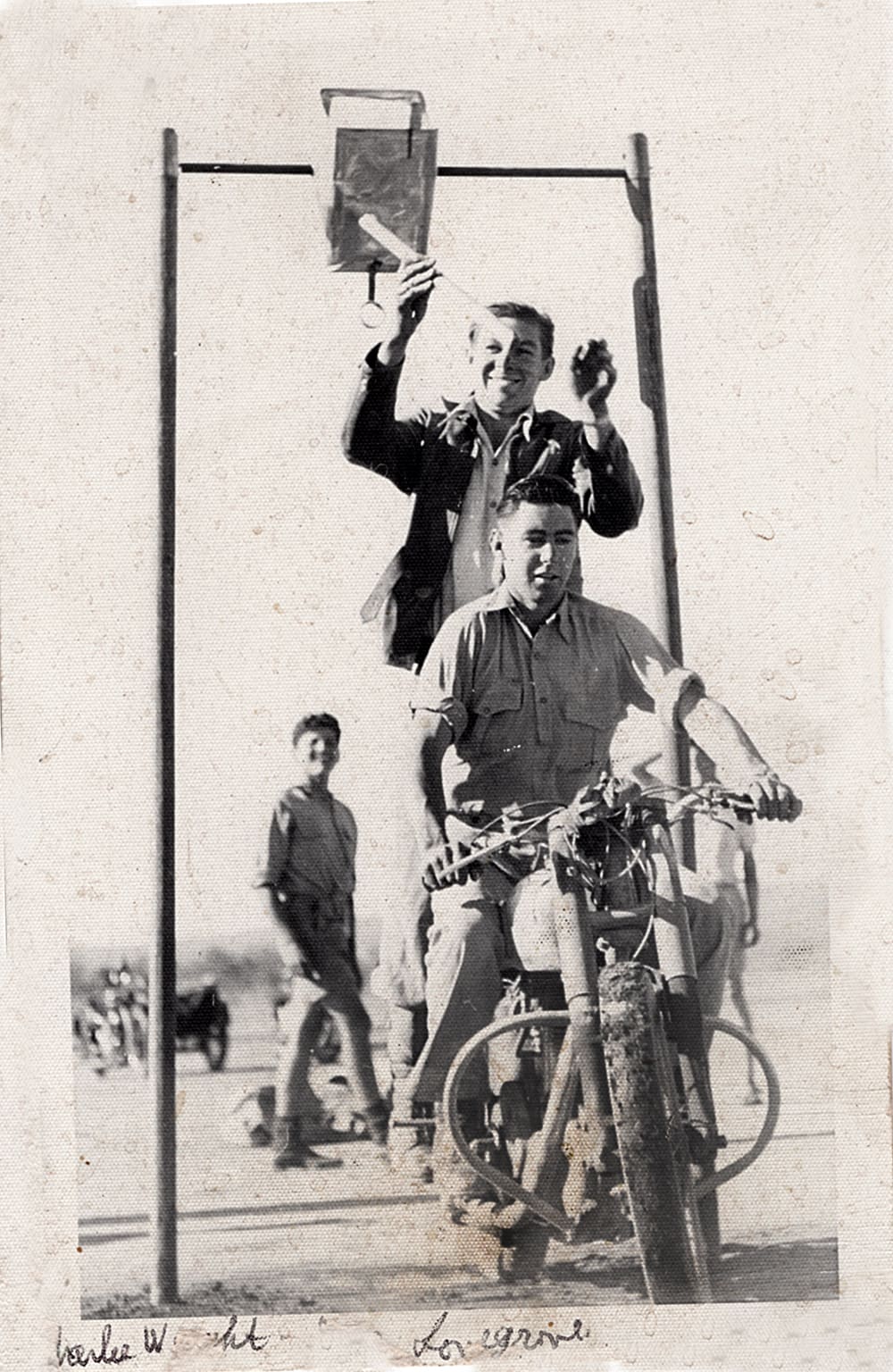

The local newsagent, Gordon Nichols, was elected president and his wife Victoria would act as club secretary. Not only did the ASMCTC members take pride of place in the Jubilee Day Parade of gaudily decorated floats, they also provided a display of trick riding on the town’s oval. Low-key Saturday afternoon events soon followed and, barely seven months after the club’s inauguration, their first time trial was recorded as a victory for Ken Reeves with a time of two minutes and 49 seconds over two miles.

Only one year later, the ASMCTC announced the introduction of a campaign to reduce the incidence of noisy motorcycles in town and the intent to penalise club members who breach road etiquette. They also announced plans to build a circular graded track on which to hold a sports day where members would perform novelty and speed events.

Then, on 10 October 1952, the Centralian Advocate published the following. “Floodlight Racing Soon”, the headline read. “A new sporting attraction may be underway in Alice Springs. Speed motorcycle racing under floodlights will be organised by the now very progressive Motor Cycle Touring Club”.

The former airstrip on the seven-mile claypan had now become a speedway and the Advocate went on to report, “the idea would provide entertainment and thrills to the local folk on warm summer nights.” The new club secretary, Ian Morrison, was quick to point out that in future all members taking part in speed events would be required to wear crash helmets.

A generator and a couple of arc lights or not, many club members were disinclined to take part in sliding around a quarter-mile claypan on their heavy British roadbikes. Most remained content performing donuts on Saturday afternoons and taking the occasional club run up the gravel highway to the Aileron roadhouse for a barbecue and a beer or two before the – often death-defying – 200km return to Alice. So there was great excitement when Ian Morrison announced the outback’s first endurance test; a ride out to Palm Valley and back.

Interest waned considerably when members realised they’d have to carry their own lunch and there was no pub at the turnaround point. The track out to the Hermannsburg Mission was said to be ‘as rough as guts’ and the final 20km into Palm Valley would be beyond the reach of the breakdown truck.

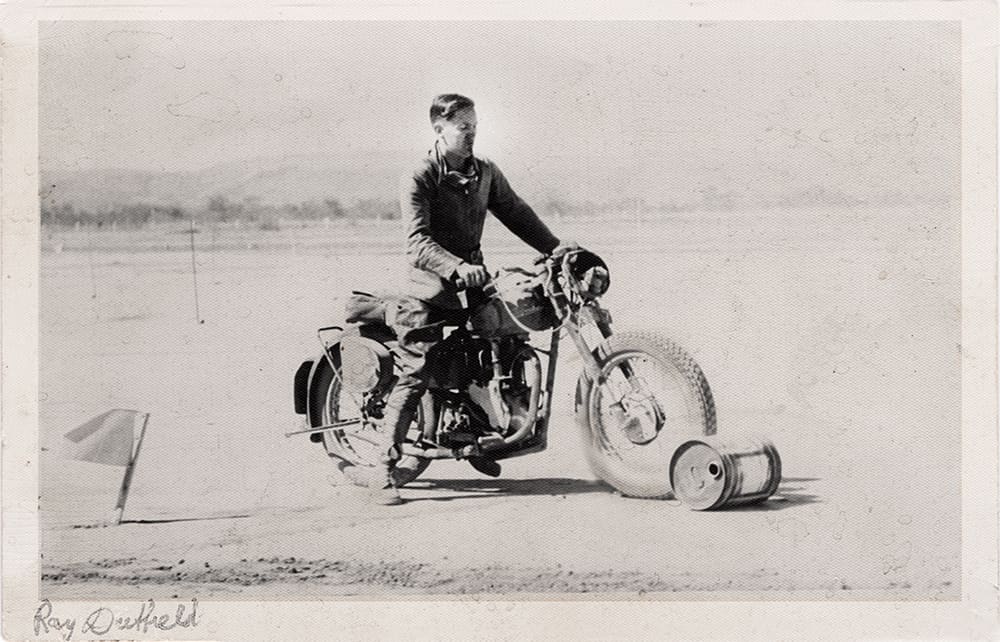

This first ‘there and back’ was a classic reliability trial, with four control points and three points lost for an early or late arrival at each time control, but come race day, 22 November 1952, the regulations became irrelevant because a massive thunderstorm turned the red centre into a mud bath. Yet with the two race stewards, Ian Morrison and Reg Osbourne, somewhere out in the Mulga, the first competitor headed into the gloom on a 125cc CZ two-banger. He was followed, at two-minute intervals by the best of British and a pair of Harley-Davidsons; nine competitors in all.

At the first control, only 30km west of Alice, five riders called it quits. Fifty kilometres later, chief steward Morrison crashed, taking two other riders down with him. After de-watering their bikes, they too returned to Alice Springs.

Only three riders continued, two competitors – Ray Mason and Ian Lovegrove – together with race steward Reg Osborne.

“We watched them slipping through sheets of water and wondered if it could be done,” said Morrison. And to this day, only those three riders ever knew how enjoyable a soggy sanga can taste in Palm Valley on an even soggier Saturday afternoon. But, before nightfall, at an average speed of little more than 20km/h, their three BSA Gold Stars made it back to Alice, where Osborne had little choice but to call the trial a dead heat.

Little wonder enthusiasm for such events began to evaporate. Even interest in dirt track was in decline as competitors learnt that racing fully equipped roadbikes was proving costly – even when they avoided personal injury. As always, there were a small number of racers keen to throw the leg over at any opportunity, yet despite the best efforts of the re-elected president Gordon Nichols, club membership had stalled at 32. And the roll-up for the 1953 season opener, a tour to Corroboree Rock 30km south-east of Alice, was disappointing.

The introduction of the Yamaha DT1 in 1968 was a huge hit and, in regions where the blacktop turned to gravel just past the town’s servo, the country was soon rife with lightweight, go anywhere trailbikes.

Touring, picnics and reliability trials became as obsolete as camel trains. The motorcycle club moved its activities to a new venue along the Undoolya Road to the east of Alice, constructing a complex of short circuit, flat track and motocross facilities better suited to these new machines.

Yet the club continued to hold regular social events such as ‘there and back’ to Jessie Gap in November 1971. What better way to spend a fine Saturday evening than to ride 10 miles out of town – well clear of any authorities. Then, after participating in a game called ‘the mirror hunt’, enjoy a barbecue and a few drinks with like-minded friends. It wasn’t obligatory to spend the night, but then again there was no hurry to get back into town.

While the Arunga Park Speedway was firing, the ASMCTC was still seeking something on a far grander scale to excite the growing number of dedicated dirtbike riders. Events such as Mexican Motocross were followed by another ‘there and back’, a trail blazing race from Emily Gap down to Ooraminna Rockhole and return; leaving riders wanting more.

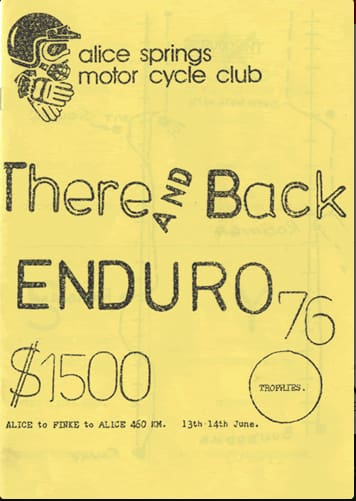

For some years there had been talk of a two-day enduro styled on the ‘Barstow to Las Vegas’ race, with smoke pyres marking the course across the desert. However the potentially devastating cost of search and rescue, followed by the inevitable litigation quashed the enthusiasm initially. Local racers Peter Gunner, Barry Taylor, Ralph Tice and his wife Alice, Paul Raybould [and 16-year-old Peter Kittle] were all in favour of a major two-day event, but it was Gunner and Taylor that were the prime movers.

Everyone agreed the Queen’s Birthday weekend in 1976 would provide ideal weather. And that Finke was the logical destination as there was a track of sorts and, in those days, a pub and a petrol bowser on the far side of the Finke River. Following the rail line shouldn’t prove too difficult, even for the most geographically challenged.

The Centralian Advocate described the route as allowing speeds of 150km/h near Alice Springs but turning into a narrow two-wheel track further south “which, in some places is barely distinguishable and dotted with huge washouts, hidden objects such as railway sleepers, long stretches of deep sand and rocky creek beds.”

There was no mention of stray cattle, kangaroos, pigs, feral cats and camels, or the number of gates to be opened and closed. Bright-orange plastic triangles nailed to the remains of the Overland Telegraph Track would assist in navigation. And the risk assessment concluded that, as all the above hazards were likely to be encountered on any ride in the Northern Territory, no additional precautions need apply.

Scrutineering consisted of little more than Chief Scrutineer Viv Johnson’s opinion as to whether the machine appeared capable of lasting the distance and the rider had enough coin for a shout at the bar.

Surprisingly the bureaucrats in Canberra responsible for Australian National Rail agreed to the race being held on Commonwealth Land. Or so it was assumed. Entry was $25 with a purse of $750 for the outright victory and $75 for a class win. Fifty-six bikes lined up for the Le Mans shotgun start and, somewhere down Bundoona way, an array of metal jerry cans lay baking in the sun ready to explode. With sketchy radio communications provided by the Alice Springs Amateur Radio Group and a sole ex-army Land Rover, carrying a pair of St John’s volunteers, on hand to sweep the course, the starter pulled the trigger.

And all’s well that ends well. Almost. Peter Stayt, who’d led the event from the first shotgun blast, ran out of fuel within sight of the finish, allowing arch rival Geoff Curtis through for the win; after a total of more than six hours in the saddle. However saddle time was the easy bit.

“It was a blast,” Curtis said a few years later. “We got pissed, slept where we fell, then rode back with splitting headaches.”

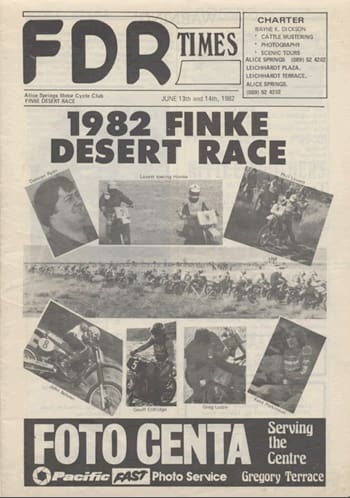

Good news spreads quickly and, in no time at all, interstate riders began the pilgrimage to show the locals a thing or two. But it was a tough ask, and it took no less than International Six days Enduro gold-medal winner Phil Lovett to temporarily overcome the local talent. And it was Lovett again who bested Aussie motocross champ and Finke rookie Stephen Gall. And it was Lovett who pressed Gall a few years later to a race record that would stand for 12 years.

What had started as a local derby was now a high-pressure, two-hour adrenaline rush, followed by an overnight rebuild and an even faster return the next day. And definitely no bibulous celebrating until the Queen had settled in with the Corgis for a post celebratory gin and tonic.

The intense rivalry between the Territorians and the Rest of the World continued, but the Outback Desert Racing Club were stretched for sponsorship and the event was in danger of folding until Gary King, the Alice Springs Honda and Suzuki dealer put up a cash prize for the winner.

It may seem like small fry now, but at the time $10,000 was bigger than the prizemoney for Australia’s iconic motorsport event – the James Hardie 1000.

And with the money came the prestige, US champion Jim Ellis and our own Craig Dack turned up to test their skills. Dack was tipped to blitz the 1987 event, but it was local rider Alan Roe who had an unbeatable lead when his mousse tube melted, allowing Dave Armstrong to become the first rookie to be crowned King of the Desert. Roe took his revenge the following year in the first of an unprecedented 15 wins for the lethal Honda CR500 two-stroke.

The single exception to a local champion was in 1996 when three-time Baja 1000 winner, Californian Dan Ashcroft halted Randall Gregory’s record of five successive victories. Ashcroft, the only international winner, assumed the perpetual trophy was perpetually his and it was never seen again.

It wasn’t until 2003 that West Australian star Darren Griffiths riding a KTM 540 demonstrated that a four-stroke could produce a Finke win. The following year Stephen Greenfield proved the Honda CR500 still had life in it, but since then the Finke has been four-stroke territory and the local influence on results waned.

Fresh from his successes in the Australian Off-Road Championship, the Hattah Desert Race and the Condo 750, Ben Grabham won the 2007 event for Honda and looked set to break Randall Gregory’s record of five straight wins. Then Toby Price lobbed. Not only was the bloke a non-Territorian, he appeared to be an extraterritorial.

Grabham switched to KTM and managed to regain the title in 2011 before deciding it might be more prudent to take on the management of the KTM Desert Racing Team. For whom Price has gone on to take the record six wins in what is recognised as the fastest and potentially most treacherous desert race on the planet,

Price’s understudy, Territorian David Walsh, is the current Finke Champion until the combatants return in June 2021.

Honour Roll

1976 Geoff Curtis/Yamaha 250

1977 Phil Stoker/Suzuki 370

1978 Geoff Curtis/Yamaha 500

1979 Peter Stayt/Yamaha 500

1980 Geoff Curtis/Yamaha 400

1981 Phil Lovett/KTM 390*

1982 Phil Lovett/KTM 495

1983 Stephen Gall/Yamaha 490

1984 Peter Stayt/Yamaha 490

1985 Phil Lovett/KTM 495

1986 Stephen Gall/Yamaha 500

1987 David Armstrong/Kawasaki 500

1988 Alan Roe/Honda 500

1989 Mark Winter/Honda 500

1990 Mark Winter/KTM 540

1991 Randall Gregory/Honda 500

1992 Randall Gregory/Honda 500

1993 Randall Gregory/Honda 500

1994 Randall Gregory/Honda 500

1995 Randall Gregory/Honda 500

1996 Dan Ashcroft/Honda 500

1997 Stephen Greenfield/Honda 500

1998 Stephen Greenfield/Honda 500

1999 Rick Hall/Honda 500

2000 Stephen Greenfield/Honda 500

2001 Michael Vroom/Honda 500

2002 Rick Hall/Honda 500

2003 Darren Griffiths/KTM 540

2004 Stephen Greenfield/Honda 450

2005 Jason Hill/Honda 450

2006 Ryan Branford/Honda 450

2007 Ben Grabham/Honda 450

2008 Ben Grabham/Honda 450

2009 Ben Grabham/Honda 450

2010 Toby Price/KTM 450

2011 Ben Grabham/KTM 450

2012 Toby Price/KTM 450

2013 Todd Smith/Honda 450

2014 Toby Price/KTM 500

2015 Toby Price/KTM 500

2016 Toby Price/KTM 500

2017 Damon Stokie/Yamaha 500

2018 Toby Price/KTM 500

2019 David Walsh/KTM 500

2020 Cancelled