You must rise through four classes of racing to reach the pinnacle of MotoGP. But how do you conquer each stage? How do the motorcycles and their technology change as the journey unfolds? AMCN MotoGP analyst Peter Bom takes us on an epic origin story, unveiling the trials, transformations and triumphs that shape a true MotoGP hero…

WIZARD OF RACING: Been there, done that!

Peter Bom, AMCN’s latest recruit to our MotoGP coverage, is one of the most respected commentators in the series. His keenly-considered analysis is based on a career as a crew chief that saw him help guide Cal Crutchlow to the World Supersport title in 2009, Stefan Bradl as Moto2 champion in 2011 and Danny Kent in Moto3 in 2015, the first British GP world champion since Barry Sheene in 1977. Bom is one half of the popular Oxley Bom MotoGP Podcast, where he teams up with AMCN’s Mat Oxley to share insights as the season unfolds. Bom is also presenting exclusive analysis videos for AMCN of each MotoGP round this year, which you can watch on amcn.com.au as well as our social media channels.

MotoGP’s Yellow Brick Road

The road to the MotoGP class runs through Moto3 and Moto2. Each of these classes has its own challenges. If you overcome these, you can move on to the higher class. Once in MotoGP, at the top of the pyramid, you still have to learn new things. Come on this imaginary journey, and together we will go from minibikes to MotoGP!

Young warrior takes up the challenge

In the run-up to the Moto3 world championship, we played and raced every free hour from a very young age. First it was simple minibikes, later with slightly larger dedicated racebikes, such as the Ohvale. We didn’t really analyse anything back then; we rode with our talent and our fighting spirit. But losing was terrible and more than once we cried away our anger when things didn’t go the way we wanted.

Off to Spain

Luckily we won a lot of races and so we could take the next step to the FIM JuniorGP in Spain. Here a lot changed for the first time. Our team no longer centred about our father and our van. Suddenly there were big race trailers and experienced mechanics who worked on our motorcycle. They were cool, these Moto3 racebikes with data analysis, adjustable suspension, super brakes and so much more grip from the tires. But we were still very young and for the first time we rode against sometimes much older and often much faster riders. Fortunately we quickly learned to give the right feedback and we listened well to the crew chief. In just a few years we had learned enough, enjoyed the battles and now we were winning a lot of them too. So it was time for the next step, to the world championships.

Moto3 madness

Although we were still riding the same Moto3 motorcycles, it was a very tough first year. Suddenly there was so much new in our lives that we perhaps didn’t get enough time to actually ride. So many different races, flights, hotels and circuits! Up until now we were used to fighting at the front, but that was definitely not the case here. Everyone was riding so incredibly fast but how did they do it? There were also journalists who started writing all sorts of things about us and on the internet there were people who thought we weren’t good enough. Suddenly racing seemed less fun. But, fortunately, we learned to deal with this quickly. Less time on the phone, more time with our team in the pit box and better at listening to our experienced crew chief and the data technician.

Their knowledge and trust helped us through that and, thanks to their experience, we were soon able to join the top riders in this class. Riding a single fast lap in Moto3 is one thing, being fast on your own and having a good race pace turned out to be much more difficult. But it was vitally important for consistent performance, so we rode a lot alone and built up our own pace. Slowly but surely our results got better and at the end of the first year we already had our first podium. An amazing feeling of achievement mixed with relief. We were good enough after all! The following two years we continued to grow, won races and even reached the top three in the world championship. That was the moment we got interest from teams in the Moto2 class. We could look forward to that. More horsepower, more speed and more grip, that sounded awesome!

Gambling with our talent in Moto2

We were fortunate to end up with a perfect team that had good technicians and were patient with a newcomer. Our expectations were at a peak and the Moto2 class seemed like it could be fun to us. We thought we could really race and, with that extra horsepower and wider tires, everything just becomes more fun, right? Not so. Riding fast on a motorcycle that was much heavier than our trusty Moto3 turned out to be much more difficult than expected. The wide tires made the steering suddenly heavier, the extra power could make the tire spin too much and there was so much more that needed to be adjusted properly in the electronics.

The first tests were anything but easy and the future seemed daunting and almost overwhelming. But the team was patient and we worked hard. In the tests, we often rode longer with worn tires, an experience that quickly helped us prepare for the second part of the upcoming races. Early in the season we found that qualifying was a very difficult skill to master. A good qualifying position is extremely important in this class. Back in Moto3 we had been able to slipstream cleverly after a poor start and get to the front but it doesn’t work that way in Moto2. Free speed doesn’t exist here so you can only finish races at the front if you also start reasonably close to the front row.

Eventually we learned to squeeze everything out of it for one lap with fresh tyres and a little fuel. Fortunately, although we initially started far back in Moto2, it only took half a season before we regularly finished in the top 10. Everything started to fall into place in our second year. We could now give better feedback to the technicians and qualified better as a result. We’d also mastered the art of saving our tyres until the end of a race and we were also physically much stronger and fitter. Even sooner than we expected, two years after our difficult start, we were given the chance to make the switch to the MotoGP class.

The team managers we spoke to told us that they were impressed by our calm and stable way of working. Plus our rapid progress. They understood how we always made our race plan based on teamwork with the technicians so we started from our own strength, not being dictated by what rival teams around us were doing. The results showed our feedback was always very precise. Our fighting spirit had also been noticed. Team managers like to see riders who often win battles. The final piece of the puzzle was also being put in place. Because we were already training with superbikes, we now knew a little bit about what the next step would involve; much more power and much more grip. But also heavier steering due to the many aero features.

Yellow Brick Road ends in MotoGP’s Emerald City

We would never forget how we felt during those first laps on a MotoGP bike. The thing kept accelerating so incredibly hard, just insane, like being fired from a cannon. The main straight on the test circuit flew by and the front wheel even wanted to come up in fifth gear! Crazy fast! We tried to slow things down in our head as our boot snicked through the seamless gearbox at lightning speed and without jerks. We saw the next corner coming at us much faster but determination took over. How cool! The brakes were so light to operate but slowed down super quick! After the corner apex, with a lot of lean angle, the throttle could be opened wide right away due to the electronics.

There was a lot to digest mentally but, strangely, we quickly got used to the speed and learned how to brake later and later. The braking procedure was totally different to Moto2 because of the aero and the sometimes low rear ride height. It took a bit longer before we also understood how to use the rear brake at the right moment to take advantage of the ride height. A few times per lap the lever on the left of the handlebar had to be operated at just the right time otherwise we lost precious seconds in acceleration. In addition, this new motorcycle steered so much heavier! The aero made everything very stable but that meant we now had to use much more force to turn the motorcycle or to change direction quickly.

Off track there was a lot to cope with too, with huge interest, now we were among the MotoGP elite. Everywhere there were photographers, journalists and people staring at us, trying to get the most candid photo or unguarded quote from us. Now we were surrounded by a team dedicated to all our needs. A chef who knew our diet and preferences or allergies, someone for our race suits, helmets and a physiotherapist to keep us supple and focused. And someone to help us handle the ever-present media. Furthermore, there were several crucial meetings with the team every day.

In these meetings we heard which tires were going to be used at what time, which electronic settings were ‘under the buttons’ in this training and especially in which order we are going to use both motorcycles at our disposal. Our data engineer explained where the other rider of the team was faster or slower than us, and why that was. Our journey to the top just needed one more stairway to climb. That involved harnessing our fears and expectations and turning this into a level of self-belief that would take us to the podium and, eventually, the MotoGP world title.

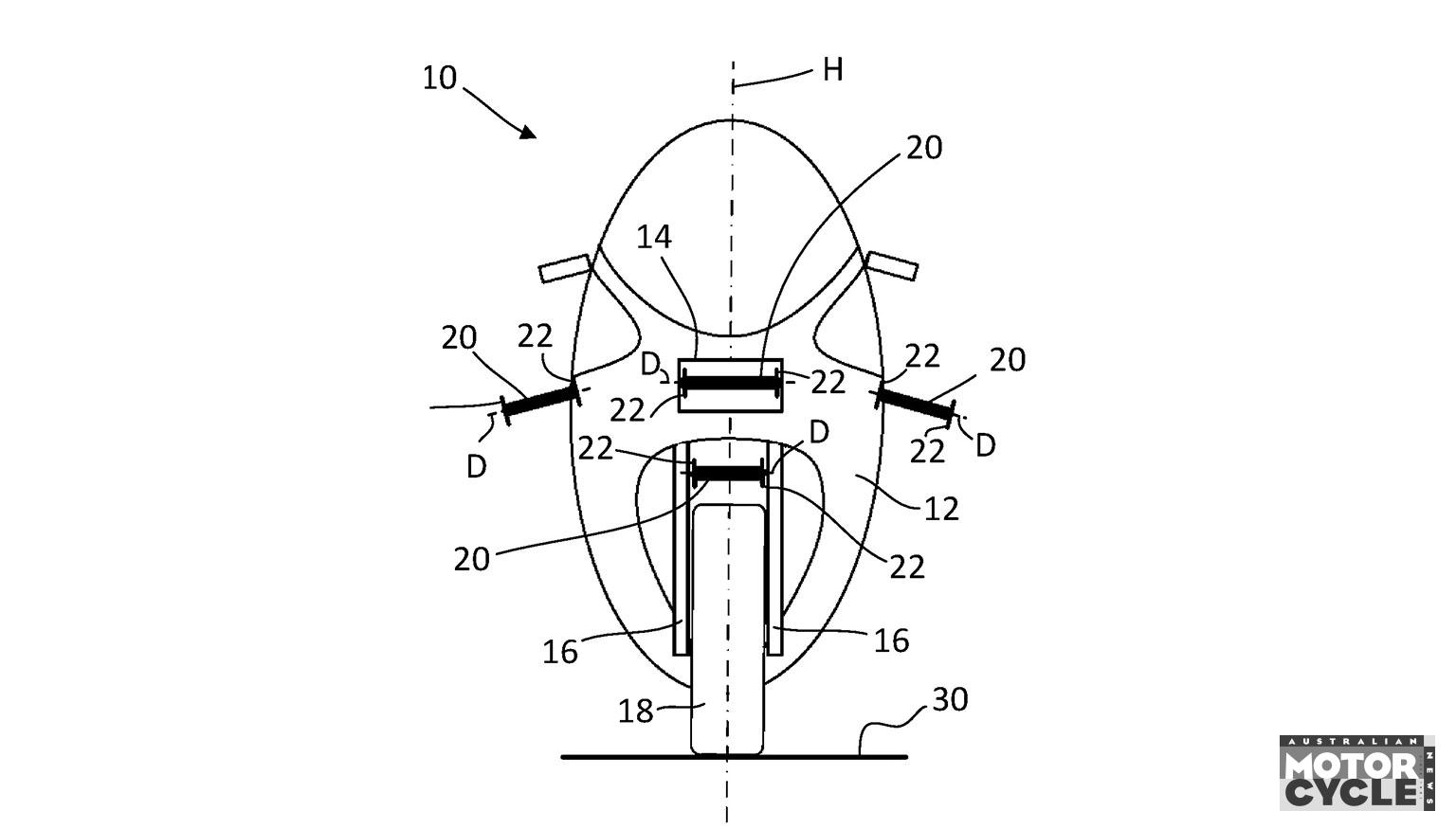

WHAT IS A MOTO2 BIKE?

The Moto 2 class began in 2010 as a reaction to the extreme prices that Aprilia and Honda were asking for a good 250cc racer at the time. Dorna came up with the idea of having specialists build their own racers around an existing engine, both to reduce costs and add variety to the grid. There are currently two suppliers active in Moto2, the German Kalex and the Italian Boscoscuro outfits. They supply almost the entire motorcycle except the engine or the front and rear suspension (which teams buy from Ohlins or WP). The ECU with the display (Marelli) are locked because these items really have to be the same for everyone. This also applies to the engine oil used (Liqui Moly 5W-40), petrol (Petronas) and tyres (Pirelli).

The differences are therefore in the chassis, which is multi-adjustable. For example, the front fork can be positioned in many ways via steering head inserts, the swingarm pivot is adjustable and there is a choice of different linkages for the rear suspension.

Exotic parts are forbidden for cost reasons. No carbon brake discs or fork legs, no titanium axles and certainly no ride height devices or special aero.

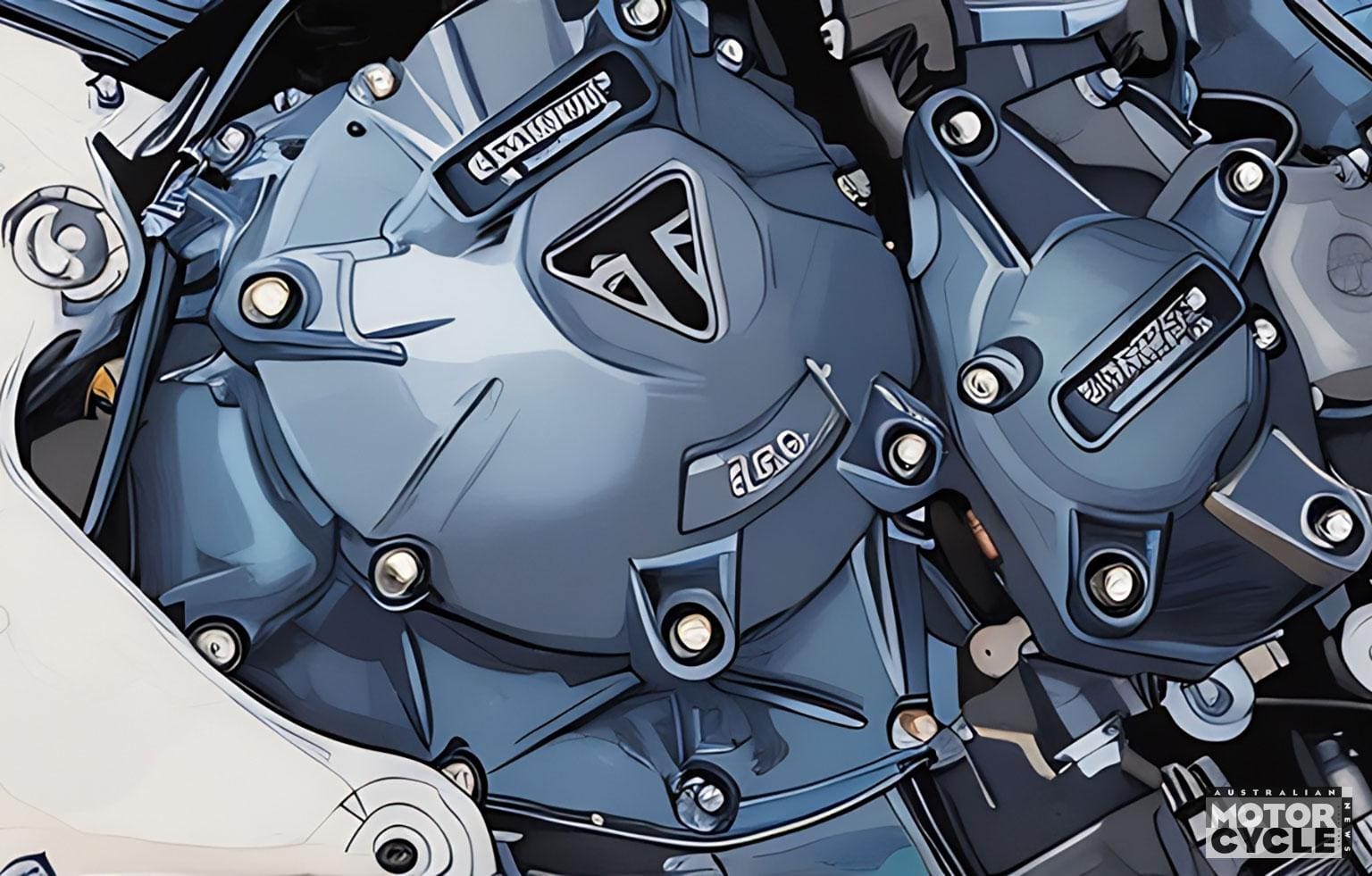

Since 2019, a 765cc three-cylinder engine from Triumph is used, based on the Speed Triple RS unit. I say “based” because the team at Triumph/Externpro really had a go at it: pistons and cylinder head are reworked for a higher compression ratio and better flow of the inlet and exhaust. Titanium valves with stronger springs allow more rpm, while a lighter generator helps spin the revs up faster. The gearbox has different ratios (higher first and second) and also now has the racing-style gear pattern. That is: neutral to sixth gear are now all in one direction (down), while neutral can only be reached after the rider switches a handlebar-mounted lever. This is to avoid accidentally hitting neutral while downshifting. MotoGP started this pattern years ago, later followed by Moto3 and WorldSB. The stock clutch is replaced by an adjustable slipper clutch, vital on a high-compression, three-cylinder racing engine.

As a result, this Moto2 engine delivers 105kW (140hp) and revs to 14,400 rpm – enough to reach a top speed of 300km/h. Compare that to the roadgoing Speed Triple that produces 79kW (106hp) at 11,850rpm and you will see how much Triumph extracted from their roadbike engine.

Teams are allowed seven engines for the 22 races each season. To ensure that all engines are the same, they are built by Externpro in Spain, which also services and leases them to the teams. A complete Moto2 racer must weigh at least 150kg while the combined weight of motorcycle and rider must not fall below 217kg.

The aim of the Moto2 class is clear: to develop talent and reduce the costs of success.

Teams and riders can make the difference by having the chassis, suspension and electronics adjusted for the many different circuits. Also important is choosing the right tyre type and run an optimum pressure. This is much more important in Moto2 than in Moto3.

Although it is certainly not as complicated as in MotoGP, a lot can be set in the ECU. The traction control is not that great, and it is not necessary with ‘only’ 140hp, but with the engine braking, for example, a big difference can be made just by setting it correctly.

WHAT IS A MOTO3 BIKE?

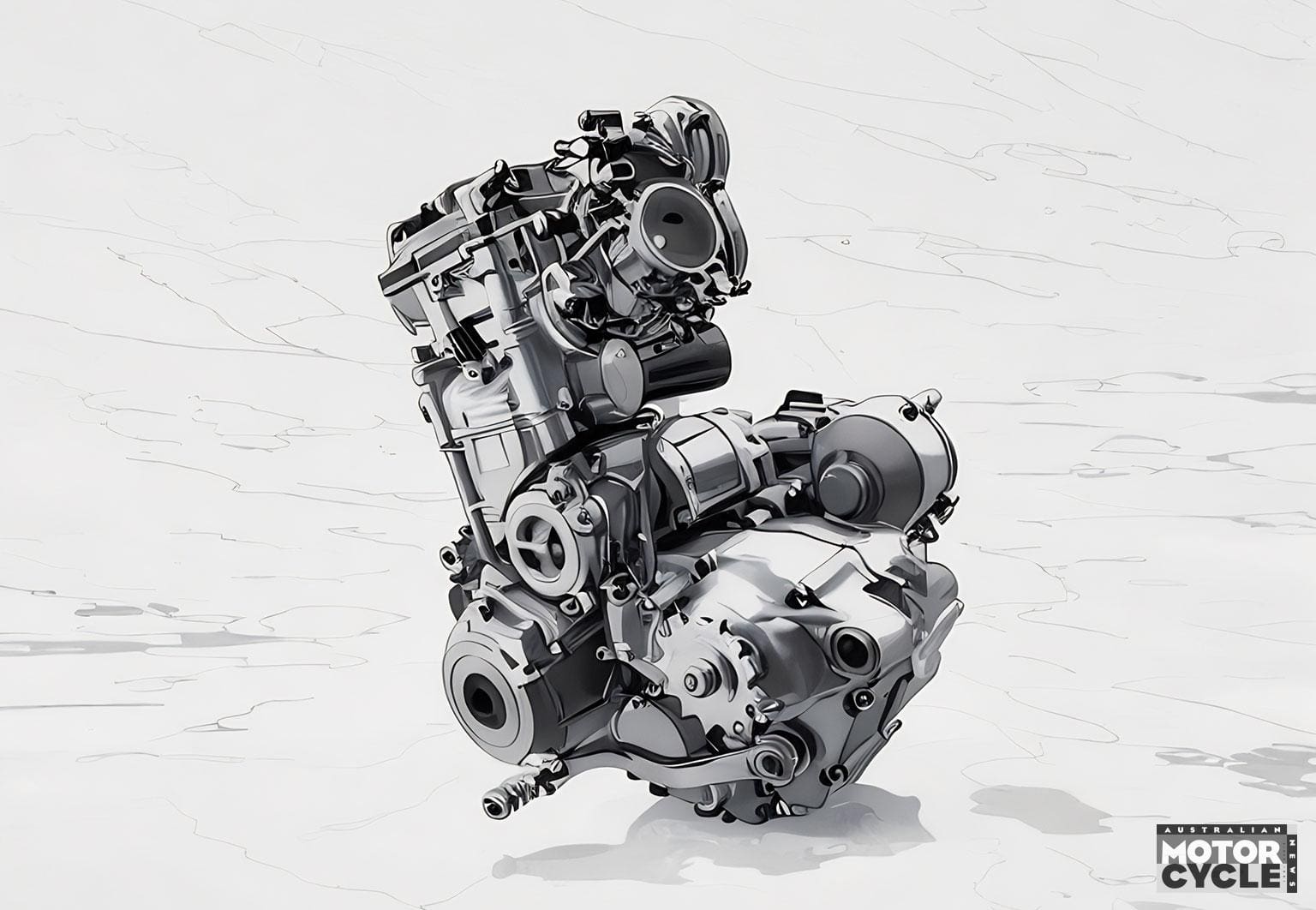

This class has existed since 2012 and these single-cylinder four-strokes now deliver 45kW (60hp) at 13,500rpm. Along with a lightweight rolling chassis, speeds of up to 250km/h can be reached. The engines are not derived from MX2 motocrossers, which you might expect, but really are prototypes. Moto3 racers ride with the throttle wide open up to 45 per cent of the time, which an MX engine block could not survive. Therefore, stronger crankcases are used, as well as improved cooling and lubrication. Remember, MX bikes have to survive in more widespread engine temperatures, and sometimes run very hot. Having two longer exhausts helps to make more power on the GP tracks. A maximum of only six of these prototype engines may be used during the entire season.

I love looking at a Moto3 bike without its fairing. These are real prototype racers where everything is very well thought out and, above all, operating very effectively.

KTM and Honda clearly have a different approach. The Honda is an aluminium twin spar frame with both exhausts high under the seat, while KTM stays true to their house style with a steel trellis design and both exhausts simply exit next to the rear wheel.

In Moto3 a unit ECU is used from Dellorto, with the maximum engine speed of 13,500rpm fixed. Traction control and engine braking can be set as can the so-called ‘anti jerk ‘, which helps to let the engine pick up smoothly after braking. But do not expect the electronics to provide a great deal more, as not much can be achieved through the settings of this fairly basic ECU.

What can be gained (and lost) a lot are the transmission ratios. Small engines are more dependent on the correct gearbox ratios for their overall performance. That is why there are two choices for all six gears. This also applies to the primary transmission and behind that you can, of course, always play with the sprockets. The entire gearbox can be quickly removed from the engine as a kind of cassette.

The overall weight is around 82kg. I deliberately say ‘around’ because in this class there is a minimum total weight of 152kg for the combination of motorcycle and rider.

In addition to the standard ECU, Moto3 also has set (Pirelli) tires, engine oil (Liqui Moly 5W-40) and petrol (Petronas). This ensures Moto3 remains an affordable talent development class so the non-factory teams can also play a role. Hence the ban on carbon brakes and developments with aero. Moto3 riders learn to steer very precisely and to keep the midcorner speed high. Smart slipstreaming plays a major role.

The exception: Jack Miller

The only MotoGP rider who has never swung a leg over a Moto2 bike is Jack Miller. In only his second year in the Moto3 world championship (2014) he fought for the title. That performance was enough for Honda to put him on a MotoGP bike straight away. Something similar could have happened to Danny Kent in 2015. Kent won many Moto3 races in the first half of the season with a huge lead. Enough reason for Ducati to sound him out for a similar move as Miller. Unfortunately, in the second half of the season it turned out that Kent had a lot of trouble with the pressure of expectations. He did become world champion, albeit at the last minute, but Ducati’s interest was not followed up. In the following years Kent was unable to convert his talent into good performances in Moto2. How do I know this? I was his crew chief in the championship year and in his first Moto2 year.

Tough at the top

A look at the results of the first MotoGP in Thailand shows how difficult the transition from Moto3 to Moto2 is. The entire top four of Moto3 switched to Moto2 this year. Three of them finished around 21st place. A positive outlier here is Daniel Holgado. Last year’s No2 did better than expected, finishing eighth in his first Moto2 race. You can count on MotoGP managers to follow him with extra interest now because riders who quickly master the Moto2 class show a talent for adapting, something that is very important in MotoGP.

Those who know

Kalex founder Alex Baumgartner knows more than most about the step from Moto3 to Moto2: “We see that the rookies in Moto2 often make the mistake of braking too late, which causes them to end up too wide in the corner and miss corner speed. That, and riding that one fast lap in qualifying is often difficult for them.”

Red Bull KTM’s MotoGP team manager and owner of KTM Ajo Moto 2 team Aki Ajo has another take on the difficulty of transitioning:

“We teach our riders the right way of working at a very young age in the FIM JuniorGP and in our Moto3 team. So what feedback they need to learn to give to the crew chief, how to stay calm and work on the right things, how to behave with the press, how to train. Everything we know they need to do, we start with very early. But at that young age they have no life experience, which is why I hardly talk to Pedro Acosta about the technique or riding at the moment. Instead, we talk about life itself. Because they are not yet fully grown up, they sometimes need help with that. Before we go into business with a young talent, we look very carefully at his attitude, his background, family and friends. With that we try to estimate whether he would be suitable for modern motorcycle racing.”