The Australian Tourist Trophy was traditionally our biggest event, but by the mid-70s its importance had faded after it was replaced as the official national championship by the multi-round series introduced in 1973 as the Australian Road Racing Championship. So when a mysterious promoter stepped up with a bid to stage the once-great event in February 1976, the Auto Cycle Council of Australia (now Motorcycling Australia) jumped at the chance.

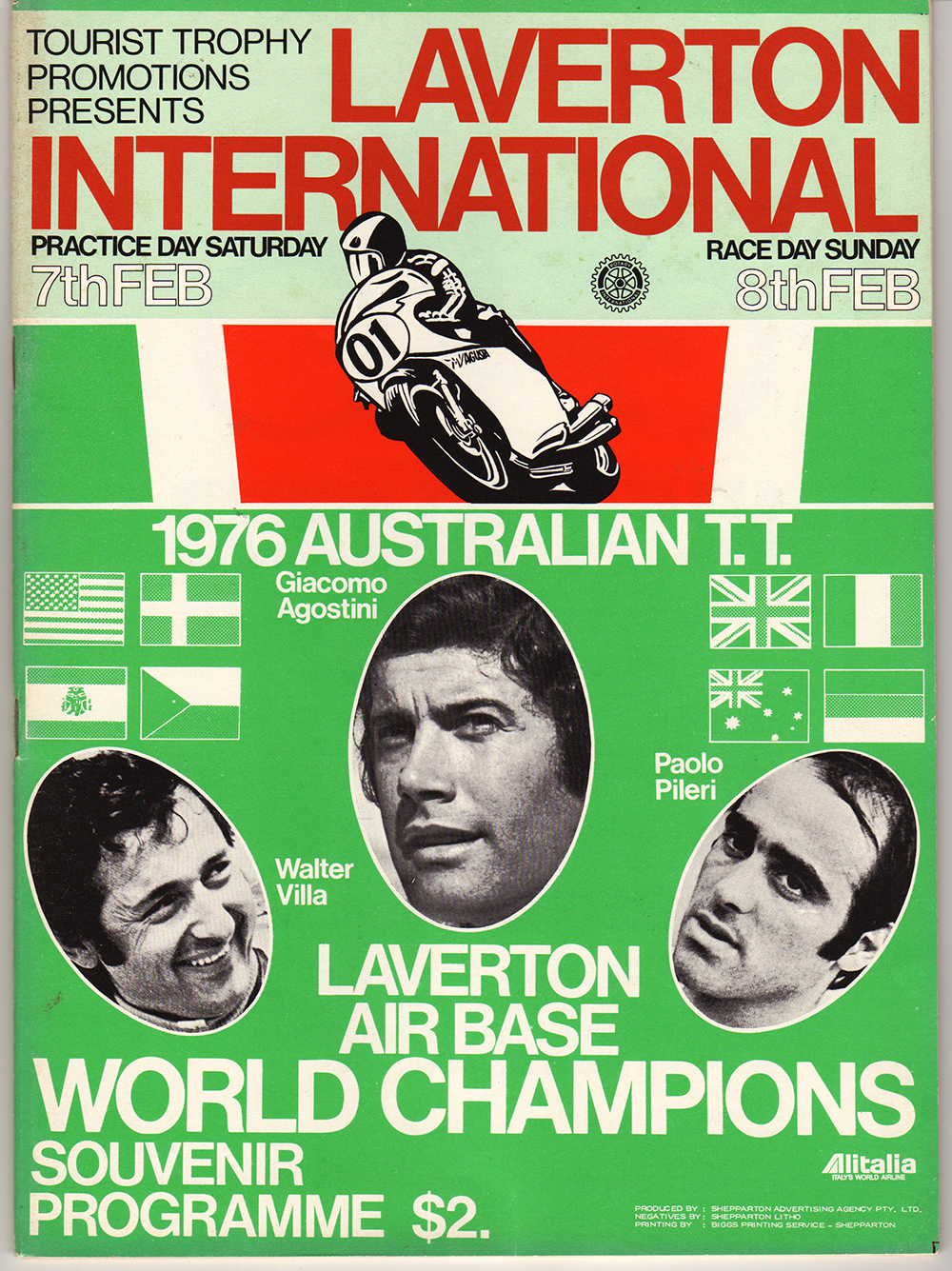

The promoters called themselves Tourist Trophy Promotions, a division of Besa Pty Ltd, and announced in October 1975 that they had signed contracts confirming the appearance of eight top GP riders, including Giacomo Agostini, who had clinched his 15th world title only one month earlier, world 350cc champion Johnny Cecotto, world 125cc champion Paolo Pileri and 250cc title holder Walter Villa.

Hartwell MCC president Murray Nankervis, who was also a director of Besa, told the media that TT Promotions would run the event at the ramshackle Phillip Island circuit on 7-8 February 1976. Hartwell MCC was named the official organisers, with the backing of Rotary International, of which Mr Nankervis was also a member. Rotary District 280, which comprised 54 Rotary clubs in the Melbourne area, had funded a trip to Italy by a representative of the promotional company to negotiate with riders and managers.

“Rotary will be getting a percentage of the gross gate receipts, but one of our ambitions is to show the FIM that Australia can host a major international meeting” Nankervis said. “Ultimately, we want to see the Australian Grand Prix revert to a one-meeting affair instead of a six-round series, so that meeting can become a round of the world championships.”

The announcement coincided with two major events in the GP arena – Yamaha’s threatened withdrawal from entering official teams, and the release of the new square-four RG500 Suzuki. Agostini didn’t hang around waiting for Yamaha to decide what it would do, announcing that he was returning to spiritual home MV Agusta with his number one plate. So the RG500 made its debut at the Indonesian GP in November 1975, with Australian Bill Horsman and Kiwis Stuart Avant and John Boote among the riders chosen to ride the exciting newcomer.

Meanwhile, Phillip Island was quietly dumped as the venue for the TT, to be replaced by a new 5.3km layout on the Laverton Air Base, 22km west of Melbourne. This was supposedly a strategic move to tap into the city’s large Italian population.

Victorian champion Bob Rosenthal inspected the proposed circuit with his new TZ750 Yamaha, declaring the machine under-geared despite reaching 290km/h. The surface, which had been sealed with hot-mix bitumen less than a year earlier, was described by the promoter as “like a billiard table”. The layout incorporated the main east-west runway, with a roughly square section of mainly right-hand corners at the western end.

Cecotto withdrew in December, and was replaced by Aermacchi Harley-Davidson rider Gianfranco Bonera. Adding to the international line-up was the Dieme-Yamaha squad of Giovanni Proni, Otello Buscherini and Attilio Riondato, Pierpaolo Bianchi on a 125 Morbidelli, Japanese stars Sadeo Asami and Yamachan Yamasaki, American Pat Hennen, and Ago’s younger brother Felice Agostini on a 250 Yamaha. Avant, Boote and fellow Kiwi John Woodley all had the latest RG500 Suzukis. As well as the international brigade, it seemed every top rider in Australia was entered.

Excitement grew at what would be by far the biggest influx of world talent to Australia, but problems began to crop up. The security company contracted for the event was sacked – the fee of $3000 deemed excessive – and private individuals hired to collect gate receipts. Sceptics maintained the TT would not happen, which did little to calm the nerves of those who recalled the previous international invasion, the ill-fated Moto Crosse (sic) series of 1972, when the promoter went bankrupt the day after the last race.

Christmas came and went, and preparations proceeded apace. With a week to go even the sceptics had gone quiet. The Rotary connection worked well in the right places. No less a chap than Prime Minister Malcolm Fraser (owner of several Bultacos purchased from Bert Flood) would be there as guest of honour along with his employment minister, former rider and sponsor Tony Street. Special trains were deployed to handle the anticipated massive crowd, stopping at a station within the air base.

And massive the crowd was, although just how massive would remain a key question in the events that followed the meeting. But there is no disputing that spectators enjoyed a feast of brilliant sport, with one performance in particular that has gone down in local racing legend.

The circuit itself was a major factor in this. Fast and smooth, the track permitted speeds usually only associated with Conrod Straight at Bathurst, and the section linking the twin straights also proved to be testing and spectacular. By and large, the internationals praised the track.

Under a relentless sun, the meeting began with the 125cc TT, and the works Morbidellis were clearly going to make mince meat of the field. Testing at Calder, the two little blue-and-white twins had equalled the 250cc record!

Ray Quincey on Clem Daniel’s home-brewed CSD made a fast start, but Pileri steamed past on the first run down the straight, followed soon after by teammate Bianchi. The locals were struggling with the switch from the normal alcohol fuel to the petrol supplied by the RAAF under an FIM permit, with reigning Australian champion Geoff Sim and quick qualifier Dave Burgess (Kawasaki) falling victim to engine gremlins. Pileri finished 38 seconds ahead of Bianchi, while Quincey was almost a minute further back.

Junior Sidecar was another drawn-out affair, with Alex Campbell and Jim Pearson from South Australia winning with ease. The pair had finished an excellent seventh in the Isle of Man 500cc Sidecar TT, the experience clearly polishing an already sharp act.

Although the 500cc Senior TT was touted as the day’s main event, the 15-lap Unlimited (750cc) TT held big interest for the crowd, being another episode in the Gregg Hansford/Warren Willing contests that had been going on since the memorable 1974 TT at Bathurst.

But it was American Pat Hennen and his Daytona-spec Suzuki who took the fight to the blond Queenslander, despite giving away about 20km/h in top speed to Hansford’s new water-cooled Kawasaki. The lead changed every lap, the pair constantly crossing the line shoulder to shoulder, but just when a photo finish looked likely, the Suzuki’s clutch began to slip, forcing Hennen to settle for second.

During the lunch break, Minister Tony Street hopped aboard the 250cc Honda-4 that had been ridden to many victories by Kel Carruthers for a lap of the track. Kel himself had flown in from his base in the US to act in an advisory role on the design of the circuit. Course marshal Kevin Donnellan was happy to oblige the PM’s request for a few laps in his Porsche Turbo, although Mr Fraser’s large minder insisted on squeezing sideways into the miniscule rear seat. After a lap at moderate pace, Mr Fraser gave it some throttle and was reportedly delighted as the Porsche slithered through the bends. It wore out a set of tyres during the course of the weekend.

The lunch break over, it was time for the big one, the Senior, even though it had the smallest field. Nevertheless, on the grid were no fewer than eight Suzuki RG500s, Agostini’s MV Agusta (a well-used 1974 model), Bonera’s vicious H-D twin, and a host of Suzuki 500 and Yamaha twins.

While the two-strokes struggled into life, the MV fired instantly from the push start and Agostini was off, the lone four-stroke wailing its way around the flat circuit to the delight of the crowd. Behind, Woodley and Boote were early retirements with engine failures, but Avant was really in his stride and on the second lap passed Ago on the outside through the Carousel section. Trailing were the remaining Suzuki fours of Blake, Greg Johnson, Laurie Barnett, Peter Jones and Bill Horsman, the last still recovering from a big fall two weeks earlier.

As Avant cruised away in front, Agostini soon had another aggressor to contend with, and on lap eight Blake passed the Italian on the Western Straight. It looked like this would be the finishing order as the gaps between the leading trio stabilised, but then came heartbreak for Avant as his Suzuki seized at the hairpin, casting him unceremoniously down the road. Blake accepted the gift and to thunderous applause from the crowd blasted home on his Jack Walters-entered Suzuki to claim the biggest win of his career. Behind Agostini came the Suzukis of Johnson and Jones. As the placegetters were driven around the circuit on the back of a truck, fans swamped the circuit and the truck quickly detoured across the infield to make it back to the finish.

It took some time to restore order to allow the 250cc TT to get underway. When it did, reigning world champ Walter Villa took charge to head home Buscherini and Proni, with Felice Agostini fourth. Quincey pipped Steve Trinder on the line to be the top local.

The Senior Sidecar began with chaos when Dennis Skinner lost his passenger, and the race was won at a canter by Campbell again.

The meeting concluded with the 350cc TT and for the first few laps Quincey, riding the 350 Yamaha with a special monoshock frame built by Rod Tingate, led the field a merry chase until the shock unit failed, letting Villa through.

It had been a day of high drama, but the real excitement was just beginning.

The day after the meeting, Besa Pty Ltd went into receivership with reputed debts of $80,000. Pandemonium ensued in the Italian camp as riders and mechanics missed their flights and their machinery was impounded pending overdue payment of air freight charges. Despite unofficial crowd estimates of 30-50,000, officials claimed only 13,600 paying spectators. Prizemoney had been lodged with the ACCA and was not in dispute, but the appearance fees promised to the Italian riders were either not paid or only partially paid. The Italian press went ballistic, labelling the meeting Il Scandolo Grande (the giant scandal).

Damien Cook of the BMW Club of Victoria has clear memories of the aftermath.

“My late father, John Cook, was a senior solicitor with the Victorian government. Although not a motorcycle enthusiast, he came to the meeting with us and after the races we had a drink in the Tarmac Hotel. We got home late and about 11pm Dad received a phone call which sounded quite urgent and important. He made a call to my uncle in Canberra then dashed out, and the next day was very busy trying to sort out a problem with customs and the returning of the bikes to Italy. It was late on the Monday night before he finally said he thought he had it under control.”

As the bills rolled in, the extent of Besa’s demise became clearer. Air-freight company Pandair was owed $29,000. With the European season looming, an agreement was struck whereby machinery was returned to Italy and held at Milan’s Malpensa Airport until the freight bill was met by the owners. While creditors argued their individual cases, federal defence minister Jim Killen announced a government inquiry into the TT.

Hartwell MCC honorary secretary Wes Brown issued a statement on behalf of the club, stating that its only involvement had been to conduct the practice and races – it was not responsible for collecting entry fees or paying prizemoney; in fact, it was itself a creditor of the collapsed TT Promotions. The statement also said that Murray Nankervis was no longer the president, or on the committee of the club.

“Murray didn’t set out to rob anyone,” Wes recalls, “but he was a loaded gun, full of big ideas. He didn’t think anything through. He was like a bull at a gate. When he first got the idea [of running the TT] he pleaded with me to be on the board of Besa, but I declined – it was unthinkable that the president and secretary of the Hartwell club should be involved like that.

“We had meetings with the authorities out at Laverton – police, council people and so on – and they kept asking him questions like, ‘Where are all these people going to stay, what about toilet facilities?’ His answer was, ‘They can camp in that paddock and there are toilets at the pub and the railway station’!

“The day after the meeting my wife Joyce and I were at Laverton, stacking up straw bales and fencing and cleaning up, and the Italians were driving around in a rented van looking for Murray. They were furious. But he was nowhere to be seen; he knew he was in big trouble.”

Despite the excellent racing, there were numerous complaints from spectators, including the $5 admission charge plus $2 for a program, restricted viewing due to the flat nature of the circuit, poor toilet facilities, and lack of a proper public address system (the latter problem partially due to the RAAF radar interfering with the radio-linked PA system). Skirmishes broke out in the temporary grandstands when people who had paid an extra $7.50 at the gate found their seats already occupied because there was nobody on duty at the stands to check tickets. Compounding this problem was that of the three ‘reserved grandstands’ only one had been built!

And so it was that the meeting that had promised to put Australia on the world map merely succeeded in branding the country – at least in the eyes of the FIM – as a bunch of colonial bandits. The Laverton event would be the last Australian TT to be run until the venerable title was revived at Bathurst in 1993, while the projected world championship Australian Grand Prix would have to wait another 13 years before it finally came to Phillip Island.