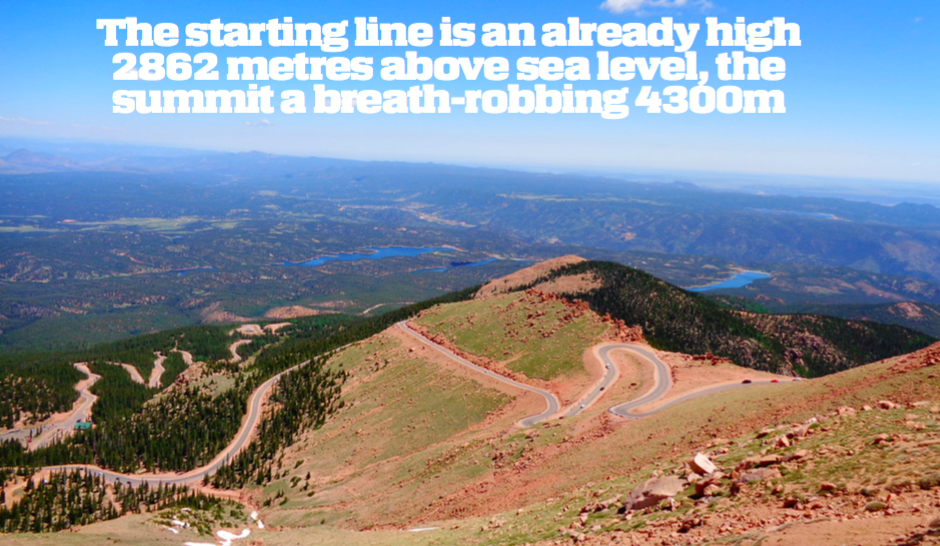

Since motorised sport began well over a century ago, there have been some oddball events tried, and mostly abandoned. One that has survived the test of time is the Pikes Peak International Hill Climb – a sinuous clamber of almost exactly 20km (12.42 miles). The starting line is an already high 2862 metres above sea level, the summit a breath-robbing 4300m. The road rises at an average gradient of seven per cent, and there are sheer drops of 100m or more throughout the journey.

Perhaps surprisingly, only six deaths have been associated with the event over its history, the first being a car driver in 1921 and the most recent, motorcycle competitor Carl Sorensen in 2015. There have been more fatalities in international hammer throw competition than at Pikes Peak!

For 51 weeks of the year, the road to the summit is part of the National Park, but is closed to normal traffic for strictly regulated periods during race week. It’s an uneasy alliance but one that seems to work.

And so to June 2016 – 100 years after the first vehicles (motorcycles actually, which preceded the cars by two days) roared up the mountain, enveloping everyone in a dense blanket of dust. If you’ll pardon the obvious pun, the event has had its ups and downs since then, hitting its nadir in 2007 when it was almost cancelled due to lack of funds. The gradual tar sealing of the climb infuriated the purists, who saw the dirt surface as the great leveller of driver skill and control, probably quite correctly. With the coming of the tar, the buzzword became ‘grip’. And because the new track surface now spends eight months of the year buried under snow, the sub-surface is constantly undermined, producing bumps and corrugations that change year by year. By 2016, those bumps, particularly on the upper sections, have become so severe they would shake the loose change out of your pockets.

With great commitment, the organisers managed to struggle through the near-abandonment of 2007, never losing focus on their goal to stage the 100-year event in 2016. Every year they face targeted opposition from environmentalists, residents and people who just don’t like motor sport, but a turning point came when the Pikes Peak International Hill Climb organisers captured the iconic Broadmoor Hotel and Resort as the naming sponsor, giving much-needed civic cred to the event. As speeds rose due to the new surface, so did the intensity and severity of the accidents, and two recent motorcycle fatalities further armed the critics. With the determination to make the 100th year safe and spectacular, they decided to limit entries to just 100, each carefully vetted to check the skill of the rider/driver and the calibre of the vehicle. Bikes were given approximately one third of the entry list – a total of 33 in the various classes.

Rise and shine

I’ve been at racetracks in the early hours all my adult life, but usually the sun was up. However, like the Isle of Man TT, this track is a public road apart from the strictly regulated periods when it is a racetrack. That means rising around 2am for each of the practice periods (even earlier if you are staying out of Colorado Springs) and around 1am on Sunday’s race day, when vast queues form at the gate of the National Park. If you want to watch from anywhere on the upper sections you need to be there before the roads close at around 7am and be prepared to stay there until they reopen late in the afternoon. You need to bring plenty of water, and oxygen canisters are also a good idea because there’s precious little of that element at 4300m.

For 2016, the capacity limit for the Heavyweight Motorcycle class was lifted from 1000cc four-cylinders/1200cc twins to 1100/1300, a move that enticed KTM to enter its 1290 Super Duke R. One of the two examples entered was a collaboration between KTM USA and US online magazine Cycle News, with Road Test Editor (and former AMCN staffer) Rennie Scaysbrook (who happens to be my son) in the saddle. Like every other competitor, he honed his knowledge of the track by devouring videos and playing game simulations, before finally taking part in the two-day ‘Tyre Test’ two weeks prior to the event. There’s a lot to learn in a very short space of time, with 156 corners, several of them hairpins, plus the rather chilling nature of the course itself – the lower regions are lined with stout trees and the upper section, above the tree line, are bordered by sheer drops and huge boulders.

For the tyre tests and for practice/qualifying, the course is split into three sections, with cars and bikes alternating between sections on the various practice days. The only time they get to run over the entire length is on Sunday’s race day, and they only get one shot at it. And once your run is complete, you’re stuck on top of the mountain until the final vehicle arrives. For the motorcyclists, who go first, that means most of the day. The lower section, beginning at around 2750m, accounts for approximately half of the distance and is extremely fast, requiring major commitment to keep the throttle pinned. Section two contains most of the hairpins and as the vegetation disappears, the air gets thinner and petrol engine performance drops notably. By the time you hit section three engines have lost around 30 per cent of their power, and that’s where the electric bikes come into their own.

Rennie came away from the tests with the fastest time on the lower section, but admitted he was well off the pace on the top. “I really like the first bit,” he said. “It’s like a really quick road race but you have to convince yourself to not back off and commit to the corners or you lose speed. You have to get the turn-in points exactly right, because if you apex too early you run wide, and that’s definitely not a good idea as there is zero run-off.”

The cars and bikes each have one designated qualifying session run over the lower section to determine starting order (and bragging rights), and for the bikes this was on Friday morning on the final day of practice week. It came down to a thrilling shoot-out between the two factory entries from Victory – journalist Don Canet on the Prototype Empulse RR electric bike and 2014 motorcycle winner Jeremy Toye on the Project 156 V-twin, Corsican hill climb specialist Bruno Langlois on a Kawasaki Z1000, Shane Scott’s KTM 1290R, and Rennie, the audacious rookie. Qualifying was conducted over three runs and after the first Canet held a narrow advantage over Rennie with Toye third, but in the second run Rennie edged ahead with a time of 4m16s. It all came down to the final attempt and with a large gulp of oxygen from the canister, Rennie peeled of a run of 4m14s while Toye remained several seconds in arrears. All eyes were glued to the timing screen as Canet’s Empulse RR silently whooshed off the line but by the first split he was 1.5 seconds down on Rennie’s time. In the critical final split Canet struck machine troubles and the honour of being fastest qualifier went to Rennie – the first rookie to do so according to those who knew the year-by-year statistics.

There was no time for celebrations, however, because Friday evening is Fan Fest. The Main Street of Colorado Springs is closed off and 35,000 people jam the area to see the competitions vehicles and collect autographs. Saturday is termed a rest day, but there’s little rest for the officials and volunteers who work feverishly to make sure everything is in place for Sunday’s big event.

The great escape

“That was the most terrifying thing I have ever done”, said Rennie through chattering teeth, draped in an Australian flag and scarcely able to climb off the bike. It was 6.15pm on Sunday, and competitors had finally returned to a start area shrouded in darkness after spending many hours on top of the mountain, where a blizzard had been raging since late afternoon. Half-frozen, physically and mentally drained, and with a large bruise on his arm, Rennie had been on the peak – as snow and sleet set in – since 10.30 am, but he was lucky to be there at all. After setting the fastest times in the first two sectors, he crashed at the entrance to one of the right hand hairpins. “I braked at the same marker I had used in practice, but the problem was that I was going a lot faster and it was way too late. I didn’t even have time to change down; I hit the barrier in fourth gear and the bike went between the hay bales and the Armco and stopped dead, flinging me over the fence.” That was when his luck cut in, because he landed on a small area beside the fence, beyond which there was only mountain air.

Only minutes earlier, 21-year-old Scotsman Connor Toner had made exactly the same mistake, but the rider and his SXV Aprilia cleared the fence and landed far down in the valley below. His father Joseph, riding a Triumph Triple, passed the scene a few minutes later, oblivious to the fate of his son, who was airlifted by helicopter with serious head injuries (from which he has since recovered). After his somersault, Rennie quickly regained his feet and set about extricating the KTM. Back in the saddle, a precious 22 seconds had passed, and it was now raining on the last section before the summit, but he put his head down and finished his run with the second fastest time on the final few miles, despite having to dodge a family of groundhogs that decided to cross the road at the apex of the flat out left-hander, which has an unguarded sheer drop on the outside. Various bits had been wiped off the KTM, including one of the GoPro cameras, which, remarkably was found by a marshal and returned to Rennie after the race. Crucially, the transponder, although torn loose from its mount, remained with the bike, recording a time of 10m28s. The margin to the ultimate motorcycle winner Bruno Langlois (the 2015 winner) was 13 seconds. Simple maths tells what might have been; hindsight tells us it could also have ended in tragedy.

While the majority of the program – the car classes, beset by numerous accidents and stoppages – were run, the bike riders huddled on the mountain as the weather closed in. By the time the last car arrived at the finish line and the slow process of return to the start, 1500m below, began, the snow was a foot deep.

Despite the disappointment of losing the overall win, Rennie was quick to acknowledge the help he received from experienced Pikes Peak racers, particularly Greg Tracy who is the only man to record sub-10 minute times on both a motorcycle and a car.

“Greg is a fabulous guy who helped me more than I could ever imagine,” Rennie said. “I would go to him constantly and explain where I was having problems and he would sit me down and take me through the steps until he was confident that I had the message. That sort of help is just invaluable on a place like this for a first-timer like me.”

In this day and age, Pikes Peak is the sort of event that beggars belief. It is difficult to put into words just how punishing and scary it really is – a throwback to the ‘death with honour’ events of the 50s like the Mille Miglia and Targo Florio. But Pikes Peak has always been thus, and it isn’t compulsory. Whether the motorcycle side of the event survives is currently a moot point – this year, the bikes were very nearly eliminated from the program over mainly insurance issues, and only retained after the organisers and the motorcycle people agreed to exclude race-spec superbikes in favour of modified roadbikes, defined as having one-piece handlebars instead of clip-ons. With more worrying incidents this year, it can only be assumed that the pressure on the bike side will continue, but while the event remains, it is most assuredly a must see. Just remember to bring your oxygen canister and plenty of water.

WORDS SUE SCAYSBROOK PHOTOGRAPHY MICHAEL JAMES