Not many men have turned down the chance to race for the works Suzuki GP team, forfeited a ride with the Honda factory squad, and declined an offer to work as a designer for Yamaha. But Peter Williams did all of those, either for reasons of patriotism or loyalty. Except for a brief link with MZ – for whom he scored the DDR/East German factory’s final GP race victory in 1971 – he raced exclusively aboard British bikes during his 10-year racing career. That ended in 1974 with his huge Oulton Park accident when the one-piece seat/tank unit came loose on the spaceframe version of the F750 John Player Norton, causing severe injuries which have sadly prevented him from riding a motorcycle again.

Now, 40 years on after stints at Cosworth and Lotus, and in between working as a consultant for major automotive industry players, Peter Williams, 70, is back in the bike world – and he’s delving back into the past in order to move present day motorcycle chassis design forward into the future. “I like to do new things,” he says, “and that means I’m never satisfied with how motorcycles are right now, but I’m focused more on envisaging how they might be. So right from when I was at college 50 years ago, I’ve wanted to make a monocoque motorcycle – because back then Colin Chapman had designed the monocoque Formula 1 Lotus, and I thought that concept would be perfect for a motorcycle. We did indeed build the Norton Monocoque in 1973 and raced that successfully, but for various reasons it was not persevered with. Then I had my accident, Norton folded, and it all came to an end. But I don’t want to leave it at that.”

Indeed, Williams has sought to develop a monocoque-framed streetbike for the past 40 years, and now he’s decided to try to finally raise the capital to do so by building 25 replicas of his TT-winning JPN Monocoque for sale priced at GBP 74,000 plus tax, as part of a long-term plan aimed at bringing his ideas to fruition.

In 2012 he teamed up to form PWM/Peter Williams Motorcycles in partnership with Greg Taylor, owner of GTME Ltd. founded in Daventry in 2005, a specialist supplier of automotive and motorcycle engineering design services, who has extensive experience in bringing innovative products that are out of the ordinary to market. The most recent such example is the Ariel Ace powered by the VFR1200 Honda’s V4 motor, which GTME engineered from a bare concept to production ready guise for Ariel Motor Company Ltd. to manufacture, as it is now doing with considerable success.

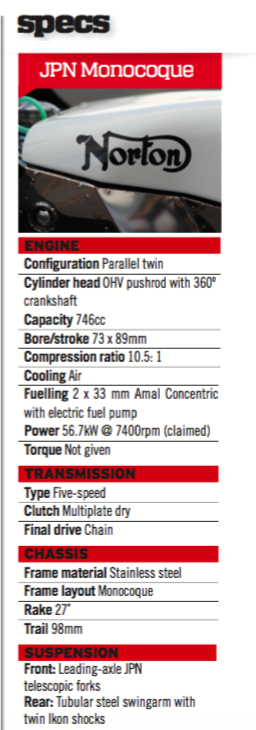

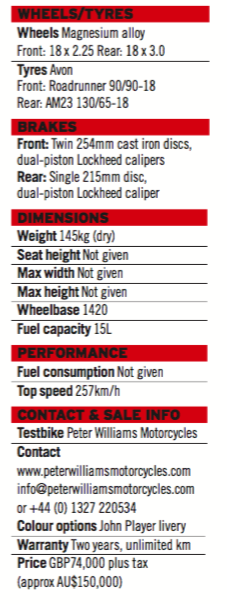

To create each replica, the PWM team manufactures the actual monocoque chassis themselves in house, rather than sourcing it elsewhere. The original frames each took the equivalent of 12 man-weeks to construct, but Peter Williams says the replicas now go together much quicker thanks to CAD-CAM manufacturing. However, perhaps surprisingly, it’s the one element in the bike which isn’t identical to the original motorcycles. “We fabricate the monocoque frame ourselves from modern stainless steel, which is much better quality than the original, as well as lighter,” states Peter. “A key benefit of getting everything on CAD, and employing modern manufacturing techniques, as compared to the original frames which we made with tin snips, and an old-fashioned bender, is that now you know everything will fit to an accuracy of two thou of a millimeter. But we’ve redesigned so the fuel tanks are no longer integral to the chassis, nor is the oil tank. We do hope these bikes will be raced, and we don’t want to force a customer who happens to crash his monocoque replica to have to pay for a new frame to be made, and then have to wait for it, too. It’s all too easy to damage the chassis with integral tanks – my TT-winning bike which lives in Spain has a crease in the chassis from where I crashed it in the Imola 200 the month before the TT. So we’ve now got two separate fuel tanks either side outboard of the chassis, which have a reduced 15 litres total capacity compared to the original which could carry 24 litres – but that’ll be quite sufficient for the shorter classic races nowadays.” Those of a literalist mindset may choose to argue that this therefore disqualifies the chassis from being termed a monocoque, if the fuel is carried separately from the frame!

“The reason the oil tank is separate on the replica is because one of the disappointing things in 1973 was that when the oil temperature was discovered to be very high I couldn’t think of a way of reducing this,” continues Peter. “So the team took it upon themselves to make another oil tank to mount at the front of the engine to keep it cool. I thought it was a terribly backward step – it wasn’t just inelegant, it was also incredibly heavy, and slightly changed the weight distribution adversely. The reason why the oil was getting so hot was because the oil tank was effectively double insulated, because it was flanked by the box frame. On the new bike the finned oil tank is still part of the structure and very much stressed, but now there’s room for air to go around each side of the tank, and the air is ducted from the front to the oil tank and then to the carburettors. That’s what we should have done in 1974 if we’d kept racing the monocoque.”

To complete the not-quite-a-replica rolling chassis the partners have fitted an tubular steel swingarm identical to the original bike’s, but instead of its Koni shocks which are no longer available, this now carries a pair of Ikon units adjustable only for spring preload. Up front there’s a re-created period-style leading-axle Norton fork with magnesium sliders, set at a 27º head angle which was considered quite racy back then with 98mm of trail, while the 18-inch cast magnesium wheels have been remanufactured from the original tooling by Creasey Castings in Sittingbourne, Kent, and they’ve been beautifully machined, then shod with Avon tyres. They carry the same brakes as the original bike – a pair of 254mm cast iron discs up front, and a single 215 mm rear, all three gripped by the benchmark twin-piston Lockheed calipers of the era. Complete weight of the Replica is 145kg dry, split 48/52 per cent rearwards, same as the original bike.

The replicas are powered by a brand-new version of the same long-stroke Commando motor as the original Monocoque, measuring 73 x 89mm for a capacity of 746cc, and built for the partners by Mick Hemmings, who needs no introduction to twin-cylinder Norton owners. It has a one-piece crankshaft with Venolia pistons, and produces 76bhp at 7,200rpm at the crankshaft. “It’s got the large inlet valve and my PW3 camshaft,” says Peter Williams. “I learnt an awful lot at Cosworth about cam design – my first job there was to design a desmodromic valve system for their three-litre V8 DFV Grand Prix engine, and just when I thought this would work nicely Renault came out with their pneumatic valve operation, and Keith Duckworth [chief engineer at Cosworth – AC] asked why I hadn’t thought of that! But I did learn an awful lot about cam design there – much more than I knew when I was at Norton. The PW3 camshaft actually accelerates more slowly than the Norton SSS camshaft, but while it opens quicker, in fact the duration is shorter than the original, so it gives super torque. It has a 10.5:1 compression ratio, just like the original.”

Their five-speed gearbox was originally the achilles heel of the tuned Formula 750 Norton twins, but the modification which resolved this is included in the latest-spec Hemmings gearbox fitted to the JPN monocoque replicas. “We’ve got the same outrigger bearing and dry clutch that we had on the original bike,” explains Williams, “which did in the end cure the gearbox trouble we had. This came about because the mainshaft with the dry clutch on it stuck out an awful long way because it had a triplex chain primary drive, and that was sufficient to increase the leverage that much more, so the pull from the chain final drive made it bend the mainshaft. So what I did then and we are doing now on the replica is to fit an outrigger bearing that represents a third bearing for the mainshaft, to prevent it from bending. It’s a very sweet gearbox to use, now.”

The chance to find that out for myself – and to become the only person fortunate to have ridden both a PJW Monocoque Replica and the bike it’s copied from, the original TT-winning John Player Norton monocoque courtesy of its owner, my Spanish mate Joaquín Folch – came on a late autumn day at a Donington Park trackday. Fortunately, this had a higher noise limit which accommodated the gloriously distinctive offbeat drone emanating from the Norton’s period twin open meggas – remember, exhaust silencers only arrived in 1976 for bike racing. Hearing the engine light up immediately stamps it as a British parallel-twin with a 360º two-up crankshaft – nothing else in the global panoply of motorcycling sounds like this. Equally unique is Peter Williams’ trademark riding position, one of the most unusual in modern-day motorcycling which I’d already sampled by riding his JPN TT-winner. The PWM Replica recaptures this completely, as you’d expect it to do seeing who built it!

The Norton is very low and slim – it’s improbably tiny for a 750 – but relatively long, so you must squeeze into a very snug, low, semi forward-reclining stance that has the seat quite far back and your arms reaching forward to the short, stubby handlebars. These position your hands very close together, next to the steering head, and are partially obscured from view by the all-enveloping fairing – don’t think about waving to the fans until after you’ve won the race, because you’d never get your hands back inside the fairing again if you did. Well, okay – anyone except Peter Williams, who had a lot of practice doing this! Pushstarts on your own are an absolute no-no, though, and probably even for him. You need to feed your body into the streamlining till you’re sitting aboard the bike with someone to push you, even though the longstroke Commando-based motor fires up very easily when you drop the clutch. Really, the riding position reminds me most of a modern-day track bicycle, with hands close together for maximum wind-cheating effect. But compared to the original TT-winner, the replica has a slightly more spacious stance, so I was actually able to get my helmet down behind the screen along the Donington straight, which was quite impossible on the original bike.

Peter Williams had a distinctive riding style where he used wide, sweeping lines in turns rather than squaring them off, a technique honed by years of racing underpowered GP singles against Italian multis, where the vital thing was to keep up momentum and maintain corner speed. Like its forebear, the monocoque replica steers beautifully in big, sweeping corners like Craner Curves at Donington, invariably holding exactly the line you set it thanks to its relatively long 1420mm wheelbase and kicked-out 27º head angle. There is however some power understeer in slower corners because of this, so when you get hard on the throttle exiting a turn, I found it doesn’t always want to hold a tight line, and pulling it back on line makes you glad that the light, precise steering allows you to counter this quite readily. It could also be that I needed to have a couple more clicks of preload on the rear Ikon shocks. But turn-in is good: the Norton goes exactly where you point it entering a bend, although the all-enveloping bodywork takes some getting used when you first do so – it does feel slightly awkward.

Within the limitations of the twin-shock rear end, the JPN Replica copes well with any bumps you meet cranked over on the angle. The fork is pretty responsive and works quite well, but by modern standards the twin Ikon shocks don’t have much travel, though that’s not so much a problem on a smooth short circuit like Donington. I know, however, from riding the shorter-wheelbase ‘74 JPN spaceframe bike in the Isle of Man that its twin-shock package gave a very lively ride over bumps, which the longer wheelbase on the Monocoque would help smooth out. By the standards of 40 years ago, the JPN Monocoque must have been a great bike for the TT or a big, fast circuit like Silverstone, relying on the low cee of gee to make it both stable over bumps and reasonably quick-steering, with you parked in place aboard the seat rather than hanging off the bike to help it to steer, as was not yet the fashion in those pre-kneeslider days.

No big surprise with a Hemmings motor, but the Replica’s engine was beautifully punchy and vibration-free, running with turbine-like smoothness while remarkably eager to rev. I’ve ridden many Norton twins down the years, both road and race, and the only engines which equal Mick’s motor in the replica for smoothness are the JPN engines that P&M’s Richard Peckett built up for the Folch bikes. It’s a pleasure to hold the throttle wide open in top gear with the engine booming away beneath you, yet no sign of the vibromassage always inflicted on me by other twin-cylinder Britbike racers. The Monocoque’s Isolastic engine mountings surely play a key role in this, to the point it’s hard to credit that this pushrod twin has no power-sapping balance shafts, and on the contrary has two big pistons rising and falling together. The turbine-like power delivery starts in earnest at 4000rpm, once the twin megaphone exhausts stop hiccuping and the engine cleans out, then builds strongly to peak power at 7400rpm, with another 200 revs available safely beyond that. “I never revved the bike higher than 7600rpm or much lower than 5000,” says Peter Williams, and after sampling his replica, I understand why. The engine picks up revs very fast, with less inertia than most other big twins of the era I’ve ridden, and suddenly it’s time to change up on the right-foot gear lever. The 5-speed Hemmings gearbox has well-chosen ratios and the shift action is sweet and precise with down for first gear, then up for the four higher ratios, but it’s definitely rather slow, so that you must use the clutch even for upward shifts. In best MV Agusta/Monza style, there’s just 500rpm between fourth and top gear – ideal for Silverstone, too – with around twice that between the other ratios. Changing up at just over 7000rpm as I did gives impressive acceleration for what at 145kg dry is quite a heavy bike. It may ‘only’ be a humble air-cooled pushrod twin, but once wound up the JPN replica motored past modern 600 fours down the Donington straight, thanks to the masses of strong, usable midrange power on tap. Nice!

I’d experienced the same mighty midrange on the original JPN TT-winner when I rode it at Snetterton and Mallory Park open practice days – but where the 600 Superstocks I remember I found myself running with there would get me back every time was on the brakes, because even by the standards of 40 years ago, the Folch-owned JPN’s 10-inch Norvil discs were a disappointment. Though gripped by exactly the same benchmark Lockheed calipers of the era as the Ducati 750SS I used to race back then and still parade, they lacked the bite of the V-twin’s larger cast-iron Brembos, leaving you to squeeze very hard on the lever to get any meaningful response, as well as stepping on the rear brake for maximum assistance. But on the PJW Replica with exactly the same brake package, that’s but a memory – for the way the new bike brakes bears no resemblance to the old one. I was really impressed with how well it stopped even without using significant engine braking, for fear of chattering the rear wheel on the overrun. There’s lots of feedback from the front discs via the brake lever, so no risk at my calmer pace of locking the front wheel as Peter Williams says he occasionally did in the heat of action in short circuit strife! Compared to the stainless steel discs on Japanese bikes back in the 70s these would have been lightyears better in terms of effectiveness and feel.

In every way, the JPN monocoque replica is a credit not only to Peter Williams, the man who conceived and rode the original first time around, but also the GTME team which has constructed such a faithfully close copy of it today. In doing so they’ve re-created what is a significant milestone in the evolution of two-wheeled chassis design. As a long-time admirer of the JPN monocoque, and with the added privilege of now having ridden one a trio of occasions, I’m left with a sense of satisfaction, as well as anticipation. I remember my feelings of frustration after the first time I rode Joaquin Folch’s original TT-winner, of which the replica is such a faithful copy with the added benefit of brakes that work! For if ever a chassis cried out for a more powerful, more sophisticated, more modern engine than the archaic anachronism the Norton air-cooled twin represented even in 1973 against its Japanese rivals, it was this one. Well, now Peter Williams and Greg Taylor have combined their talents to set out down the road of making precisely such a motorcycle achieve reality – a modern-style monocoque powered by the benchmark hypersports motor of the modern era, the Honda CBR1000RR Fireblade. You don’t have to be a PJW or Norton fan to hope this achieves reality, but here’s the start of the process for them to do so – courtesy of the bike that did the most with the least 40 years ago, and which is now available for their for their admittedly well-heeled customers to experience in replica guise.

The road ahead

“Our reason for making these JPN Replicas is because Greg Taylor and I have had to accept that we’re never going to get the finance required to make a proper monocoque streetbike unless we underwrite it ourselves,” says Williams. “So we’re making these replicas in order to raise the capi-tal to go one stage further in making the monocoque streetbike concept feasible. Next up, we’ll be making replicas of the Arter Matchless G50 Wagonwheels single I raced in the Senior TT and oth-er 500GP races, and we’ll hopefully sell a few of those. Then next we’ll make a minimalist modern road bike that doesn’t have lashings of fake carbon fibre all over it, but is a pleasure to ride. We’re looking at using the Honda CBR500 engine at the moment – it’s a 50bhp 500cc twin, and I think that’s enough power for real world riding, as long as it handles well, has good brakes, and is fun and easy to use. Greg and I have a common viewpoint – we just want to make bikes that handle beautifully, and are a delight to ride.” So will this debut PWM streetbike have a monocoque frame? “No – this is one of the several stages in raising the finance to develop the monocoque framed streetbike, but then once we’ve got enough money built up, we’ll start work on that. The mono-coque will have a four-cylinder CBR1000 RR Fireblade engine powering it. But that’s a long way off, and all will depend ultimately on how well these Norton monocoque replicas sell.”

Just four John Player Norton monocoques were built for the 1973 season [see History], one proto-type and three racebikes. The Williams F750 TT winner is in Spain, another team racer is in the USA, but the other two bikes are in the UK, and Peter Williams had access to them to create the Replicas.

“When we started the project three years ago, we were able to measure up the prototype in the Na-tional Motorcycle Museum, who were very helpful to us,” says Peter. “We also had access to Mike Braid’s racebike. He’s been an enormous help, and even had a few original drawings that he lent us, too. We digitalised all our measurements to CAD, which was the key to reverse engineering these two original bikes into creating a true replica, as well as ensuring all bikes we build will be identical to each other, and to the originals.” Construction of the first bike bearing chassis no. JPN 001 began in March 2014, once the first firm orders arrived. The partners had anticipated finishing it by September that year, but for various reasons, mainly supplier related, that didn’t happen till the following February. Since then they’ve built three bikes altogether, and two have already been de-livered to customers, with the third one retained as their own show/test bike.

“We have orders from customers for two more that are already underway,” says Peter. “We’ve learnt an awful lot from those first three, so now when someone orders a bike from us, we can confidently promise delivery of the complete handbuilt motorcycle within six months.

Avant-garde anachronism

The John Player Norton story is more than a footnote in the history of Britain’s most historic racing marque, marking a brief revival more than 40 years ago of racetrack fortunes in the face of the Japan Inc. onslaught. For the British team’s tiny Thruxton-based race team not only established the proto-type of today’s fully-sponsored race teams, it also created a race-winning bike that was a two-wheeled anachronism thanks to its archaic air-cooled pushrod twin motor and separate gearbox, yet was arguably the most sophisticated and avantgarde motorcycle in terms of chassis design that the world had yet seen, echoing Britain’s newly-established competition Formula 1 supremacy via firms like Lotus, Cooper, Brabham and Lola. That bike was the JPN Monocoque, and though only three such motorcycles were ever built (plus a fourth prototype chassis), all of which competed for just a single race season in 1973, its unlikely success against much more powerful two-stroke opposition, has granted the JPN Monocoque legendary status as one of the benchmark racebikes of the modem era. And the Monocoque was the creative masterpiece of the man who conceived, developed and rode it to victory in the 1973 F750 Isle of Man TT: Peter Williams.

Why then was this avantgarde motorcycle of proven race-winning potential discarded after just a sin-gle season of racing, in which it had covered itself with glory – not only by winning the TT and placing fifth in the USA in July’s Laguna Seca F750 race, but also coming within an ace of scooping the Brit-ish Superbike Championship against all the two-strokes – Williams and Sheene tied on points at the end of the season, Bazza only scooping the title by scoring one more race victory? The answer lies in the internal politics of the JPN team, a fact Peter Williams is painfully aware of today, which resulted in the Monocoque being jettisoned after just a single season of development, in favour of a more traditional spaceframe design that, although 12kg lighter, was much taller, less aerodynamic, and though fitted with Norton’s more powerful new short-stroke engine, slower, too – neither Williams nor Croxford could match the Monocoque’s lap times with the new bike. “Frank Perris thought I should be concentrating more on riding rather than engineering,” reflects Peter, “especially in training and pre-paring myself for races. Also, I was persuaded it was difficult to work on the engine at a race meeting, that everything was too inaccessible – though years later Norman White, one of the team mechanics, told me this definitely wasn’t so, and that he found the bike easy to work on in the paddock. So I’m left with the third and most likely factor, which is jealousy – partly my own fault, though, because when people asked me technical details about the bike I always answered with ‘I’ rather than ‘we’, which might have smoothed some feathers. But the Monocoque chassis was very much my own personal project, which I conceived, helped develop and raced myself, on behalf of the JPN team. I’m very, very proud of it, even if it was a lost opportunity.”