Is the new Triumph Daytona 660 a blast from the past? Throughout the nineties and noughties middleweight sportsbikes were big business. Supersport bikes were race-winning weapons and manufacturers, desperate to cash in on the ‘win on Sunday, sell on Monday’ sales creed, developed increasingly sharp, track-focused machinery. There was only one problem – they weren’t necessarily very good roadbikes. The evolutionary arms race dictated a trend towards ever more aggressive riding positions that placed a lot of weight on the rider’s wrists, with leg room only small people could live with. Engines were tuned to produce as much top-end power as possible, at the expense of usable torque lower in the rev range, and supersport machines ended up in no-man’s land; too track-focused for newer riders and outgunned by litre-class superbikes for those looking for the ultimate road racer.

But the middleweight sports category is once again booming now that bike makers have belatedly cottoned on to the fact that attracting younger, less experienced riders is crucial. An affordable price tag is key, along with features and ergonomics that increase day-to-day utility; think Aprilia RS660, Yamaha R7 and Suzuki GSX-8R. Now Triumph’s in on the game, too, with a new 660cc version of its successful Daytona.

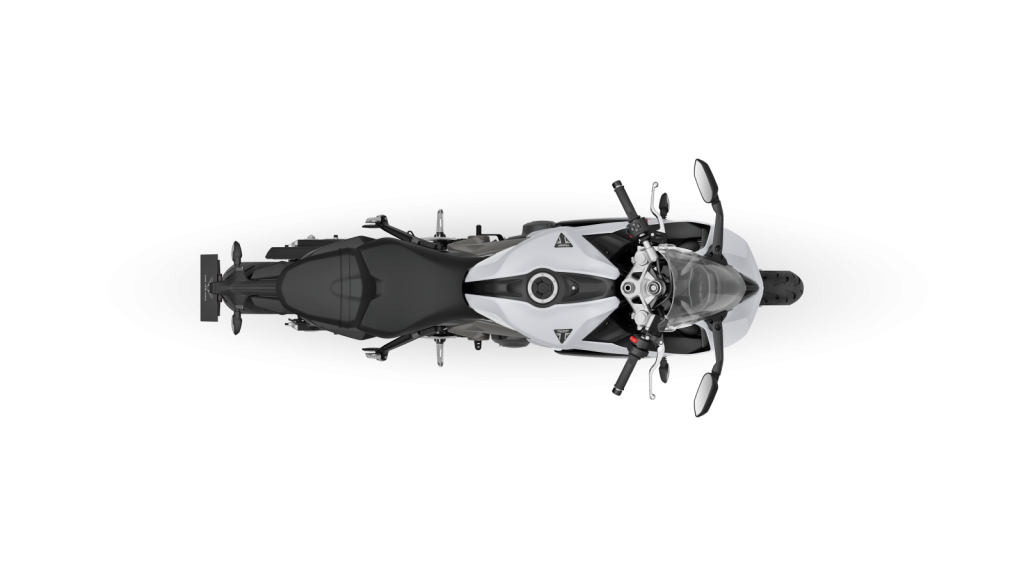

Triumph’s welterweight bikes have built a loyal following over the years for their good looks, lithe handling and charismatic engines. In 2006 the Daytona 675 took out Australian Motorcycle News’ Motorcycle of the Year gong, so impressed were we with its performance, cost and style. The new Daytona 660 carries on the tradition of a straight triple housed in a lightweight chassis, but with its ergonomics and engine response tailored for sporty road riding rather than shaving off tenths of a second at the track. The fact the new Daytona is available as a learner-approved motorcycle means Triumph can also make use of economies of scale to make the 660 more cost effective.

Triumph has thrown the feline amongst the fowls with the Daytona’s $14,790 ride-away price, too. That makes it slightly more expensive than Honda’s $13,893 CBR650R and Kawasaki’s $12,998 Ninja 650, but cheaper than Suzuki’s $14,990 GSX-8R, Yamaha’s $15,649 YZF-R7 HO and Aprilia’s $22,740 RS660. The Daytona is one of the more powerful middleweights as well as one of the better-specced ones, coming standard with three electronic ride modes, switchable traction control and ABS. Suzuki’s GSX-8R trumps it with the addition of a standard quickshifter, while the RS660 features fully customisable APRC package electronics, cruise control and a quickshifter, but at considerable extra cost.

A quickshifter is available as an option on the Daytona though, along with myriad other accessories including heated grips, comfort seat, Bluetooth connectivity, tyre pressure monitoring and pillion handles.

When it comes to chassis componentry, Showa must be doing something right, as it now supplies the bouncy bits for the CBR650R and GSX-8R as well as the new Daytona. All now feature a 41mm inverted big piston fork and rear monoshock, though with different set-ups as we’ll see later. The Daytona also boasts LED lighting all round, Michelin Pilot Power 6 rubber, analogue/LCD instrumentation, cast-aluminium wheels and radial four-piston front calipers with braided lines.

The triple-cylinder engine really sets the Daytona apart from its rivals. While this unit has been borrowed from the Trident 660, Triumph’s engineers have heavily revised the internals for more power and torque. The clutch and six-speed gearbox have also been updated, along with the three-into-one exhaust. Together these changes liberate 17 percent more power than the donor Trident, with 70kW (94hp) now available at 11,250rpm, and torque bumped to 69Nm at 8250rpm.

Learners are well catered for as well, with the LAMS Daytona producing a respectable 41.9kW (56hp) peak figure. No rounding up to 42kW though, as that figure is precisely on the power-to-weight borderline of what’s permissible under Australian regulations, making it one of the more potent LAMS machines on the market.

Approaching the gleaming row of brand-spanking new British metal in the early morning light, my eye was immediately drawn to the gorgeous white and red versions, which make the ‘Satin Granite’ look slightly dowdy by comparison to my admittedly style-blind eyes. The clean, unmistakeably-Triumph lines on all three colours look svelte, though it’s a tad disappointing that the traditional yellow-gold isn’t available. Nonetheless I quickly jumped on a lovely ‘Snowdonia’ white steed while everyone was standing around. I was forced to swap to a grey one later in the day after being rear-ended by another rider in the group.

Climbing aboard the 810mm saddle, I found a riding position that was reasonably accommodating while still being on the sporty side. The ’bar and ’peg positions may be less aggressive than previous Daytonas, but I’m pleased to see it hasn’t been totally defanged. It might be a fine line, but where the GSX-8R I rode recently felt sports-tourer-ish, the Triumph is still a sportsbike to sit on, albeit less extreme than some. The tall mirror stalks provide a clear rear view, and the seat feels nicely padded.

Turn the key and the white on black LCD screen cycles to life. It’s relatively simple to navigate through the various riding modes and settings with the ’bar-mounted direction pad. A wide array of trip and vehicle information is accessible via different instrumentation configurations on the compact LCD/analogue cluster, but while it’s nicely laid out the small screen can look cluttered.

The Daytona’s athletic feel continued as we negotiated some of South Australia’s more ‘charming’ country roads, with damping that felt poised rather than plush. The Showa suspension mostly soaked up the shoddy bitumen but, rather than just ploughing through road imperfections, I found myself weaving around the worst craters. Overall though, the ride was smooth enough given the quality of the surface.

Eventually the roads straightened into gun-barrel stretches of tarmac where the local council appeared to have a bit more infrastructure budget, giving us a chance to test the Daytona’s roll-on acceleration. The 660cc powerplant has excellent fueling, with enough punch to jerk your head back if you’re not ready for it. Triumph triples have always had the sorcerous ability to dish up strong bottom-end urge while simultaneously revving joyously up to a five-figure redline, and this Daytona is no different.

Still, for a sub-700cc engine, the propulsion seemed improbably keen – until I spotted the huge rear sprocket. The dinner-plate-sized rear cog wouldn’t look out of place on Lukey Luke’s stunt bike and explains why the midsized Daytona will wheelie off the throttle in first gear and overtakes relatively easily even in higher gears. The downside should be that the engine is working hard at freeway speeds but, although it was revving above 5000rpm, it didn’t feel unduly strained with its smooth midrange drive somewhat disguising the short final-drive ratio. You’d imagine top speed would be compromised and you’d be right, but apparently the Daytona will still do about 220km/h.

Afterwards I got a chance to sample the mechanically identical learner-approved Daytona. While top-end power is electronically reduced via the simple expedient of limiting the rev range, it too exhibits the same spirited low and midrange. Which makes sense, given the fact the engine distributes 80 percent of its available torque to the rear tyre at just 3150rpm, and the LAMS version has a similarly enormous sprocket sitting alongside its back wheel.

It’s actually an astoundingly gutsy and flexible engine for a learner bike, serving up solid, usable torque right where you need it rather than buried high up the tacho. Many riders, including myself, look back on the screaming 250cc and 400cc crotch rockets with rose tinted visors, but the Daytona LAMS 660 has far more potent and accessible real-world performance.

When the corners finally started to meld into one another I could just about hear the nimble Daytona sigh in relief and we set off down sinuous switchbacks like kelpies given permission to chase sheep. Changing rider modes is possible on the move if the throttle is closed, with Rain and Road modes providing incrementally softer throttle mapping and more officious traction control settings, but in sunny conditions Sports mode seemed fine for cruising and carving alike.

Descending Mount Lofty, the views across the valley went completely unappreciated as we scythed from corner to endless corner. Here the Daytona was in its element, the pokey engine boiling away with a nice bark while it fired from one apex to the next. In general, the non-adjustable fork offered decent damping when pitching hard into turns, without quite offering up the nuanced feel of more sophisticated set-ups, and the Triumph-badged radial calipers provided robust stopping power and feel.

I’d probably back off the rear preload a touch to settle the rear down slightly if I were riding the twisty bits regularly, with the odd mid-corner bump capable of startling the shock. This is probably the area where you most notice that the Daytona has been developed with affordability in mind, but most of the time the suspension struck

a good compromise between ride quality and chassis control.

As I warmed to the task, so too did the Michelin Power 6 hoops, providing an assured, secure feeling through the ’bars and seat as we plunged down a cascade of linked turns. The Daytona’s 201kg wet weight isn’t the lightest in the class – that title goes to the RS660, but the relatively steep 23.8-degree rake angle helps it to change direction like it’s on a giant Scalextric track. I’ve grown used to two-way quickshifters adorning modern sportsbikes, but the Daytona’s slick gearbox and light clutch meant I didn’t notice the lack of one too much. The triple’s solid midrange tow means you’re not having to constantly bang away on the shift lever anyway, and it summoned up good traction as I did my best to scrub the pesky Michelin Man logo off the tyre edge.

In Sport mode, the TC allows some slip before it calculates that your right wrist is writing cheques the rear tyre can’t cash, though without an onboard IMU the intervention isn’t as subtle as on more expensive systems.

While some purists might bemoan Triumph’s move away from razor-edged middleweight track performance, the new Daytona 660 is still capable enough to satisfy all but the sportiest of sporty riders. It may have had its claws trimmed somewhat, but it’s still a competent scrapper and, ridden well, not even the LAMS version would be left far behind on weekend raids into the hills.

The thrifty 4.9L/100km claimed economy seemed plausible despite our enthusiastic throttle use on the day, meaning the 14-litre tank should be good for a range of around 250km in normal conditions. In a perfect world a quickshifter and Bluetooth connectivity would come standard, and so would Triumph’s already excellent TFT dash, but it’s a bit nit-picky given the sharp price point. For some perspective, that MOTY-winning Daytona 675 I mentioned earlier had no electronics or ABS, and cost $100 more than the new 660 18 years ago!

This Daytona stays more true to its sporting pedigree than much of its competition while offering a wide bandwidth of everyday usability, and that gem of a triple still loves a good thrashing. As a fun, attractive and affordable dance partner, it’s going to be a tough middleweight to beat.

PROS: A gem of an engine tops a package that offers everyday usability while staying true to its sporting pedigree.

CONS: It would be good if a quickshifter and Bluetooth connectivity came standard but that would raise the price.

WELTERWEIGHT WARRIORS

2000 – Triumph TT 600

Hinckley’s 600cc sports offering met mixed reviews due to glitchy fueling, but still offered decent performance from its 80kW inline-4 engine.

2002 – Daytona 600

New Daytona 600 hits the market with much improved dynamics, weighing only 165kg dry and with the inline-4 now producing 82kW @12,750rpm.

2005 – Daytona 650

Capacity hike to 646cc increases power to 85kW at 12,500rpm, with torque also increased to 68Nm at 11,500rpm.

2006 – Daytona 675

675 hits the market to rave reviews, still weighing just 165kg but with the new triple-cylinder engine producing 92kW at 12,500rpm. Wins AMCN Motorcycle of the Year.

2011 – Daytona 675R

Package further sharpened with the addition of upgraded Öhlins suspension, Brembo calipers and quickshifter. ABS becomes standard equipment in 2014.

2019 – Daytona Moto2 765

Triple-cylinder engine based on the Triumph Moto2 racing unit produces 95.4kW at 12,250rpm. The 765 also features advanced riding modes and electronics, and ABS.

THE COMPETITION

Honda CBR650R

649cc inline four

70kW @ 12000rpm

64Nm @ 8500rpm

207kg (wet, claimed)

$13,893

Kawasaki Ninja 650

649cc parallel twin

53kW @ 8500rpm

64Nm @ 7000rpm

211kg (wet, claimed)

$12,998

Yamaha YZF-R7 HO

689cc parallel twin

56.4kW @ 9000rpm

68Nm @ 6500rpm

188kg (wet, claimed)

$15,649

Suzuki GSX-8R

776cc parallel twin

61kW @8500rpm

78Nm @ 6800rpm

205kg (wet, claimed)

$14,990

Aprilia RS660

659cc parallel twin

73.5kw @ 10,500rpm

67Nm @ 8500rpm

180kg (wet, claimed)

$22,740

SPECIFICATIONS – TRIUMPH DAYTONA 660

ENGINE

Capacity 660cc

Type inline three cylinder, DOHC, four valves per cylinder

Bore & stroke 74.04mm x 51.1mm

Compression ratio 12.05:1

Cooling Liquid

Fueling EFI, three throttle bodies

Transmission Six-speed

Clutch Wet, multi-plate, slipper type

Final drive Chain

PERFORMANCE

Power 70kW (94hp) @ 11,250rpm (claimed)

Torque 69Nm @ 8250rpm (claimed)

Top speed 220km/h (est)

Fuel consumption 4.9L/100km (claimed)

ELECTRONICS

Type Not given

Rider aids ABS and traction control

Rider modes Sport, Road or Rain

CHASSIS

Frame material Tubular steel

Frame type Perimeter

Rake 23.8°

Trail 82.3mm

Wheelbase 1425.6mm

SUSPENSION

Type Showa

Front: 41mm non-adjustable SFF-BP fork, 110mm travel

Rear: RSU monoshock, preload adjustable, 130mm travel

WHEELS & BRAKES

Wheels Cast aluminium

Front: 17 x 3.5 Rear: 17 x 5.5

Tyres Michelin Power 6

Front: 120/70-17 (58W)

Rear: 180/55-17 (73W)

Brakes

Front: Twin 310mm discs, four-piston calipers

Rear: Single 220mm disc, single-piston caliper

DIMENSIONS

Weight 201kg (wet, claimed)

Seat height 810mm

Width 736mm

Height 1145.2mm

Length Not given

Ground clearance Not given

Fuel capacity 14L

SERVICING & WARRANTY

Servicing First: 1000km

Minor: 16,000km

Major: 32,000km

Warranty Two years,

unlimited kilometres

BUSINESS END

Price $14,790 (ride away)

Colour options Snowdonia White/Sapphire Black, Carnival Red/Sapphire Black or Satin Granite/Satin Jet Black

CONTACT www.triumphmotorcycles.com.au