One key to Kevin Schwantz’s 1993 500cc world title was the recruitment of Stuart Shenton as his race engineer at the start of the 1992 season. A former Kawasaki and Honda technician who’d worked with HRC ever since Freddie Spencer’s 1985 double 250/500 championship season, Shenton understood the value of linear development of an existing design, rather than making sweeping changes from one year to the next.

He moved to Suzuki in 1992 and it was a very different winter’s work from what had gone before, as Stuart recalls.

“We actually started our winter test programme two weeks after the final GP of 1992,” said Shenton. “And we ran it right through up to two weeks before the opening ’93 round in Australia. Suzuki engineers told us it was the most comprehensive off-season schedule the company had ever undertaken, and we did a lot of work in four areas; power delivery, grip, the balance of the bike and suspension.

“It meant we started the season much better prepared than ever before, which allowed us to take the initiative and make the others worry about keeping up with us.”

The same strategy was taken with the engine, too. The title-winning engine was essentially unchanged, apart from switching from aluminium crankcases to magnesium ones, which saved about 2kg in weight and allowed the team to add stiffness in other areas, and to make improvements that cost weight.

“Our main aim was to make the bike as user-friendly as possible,” said Shenton, “with a power delivery that was more linear than progressive. It’s a process of refinement which Suzuki has continued with. And the results are there to see: look at the way Alex [Rins] was able to adapt to the bike so quickly, that he almost won his fourth-ever GP on it.”

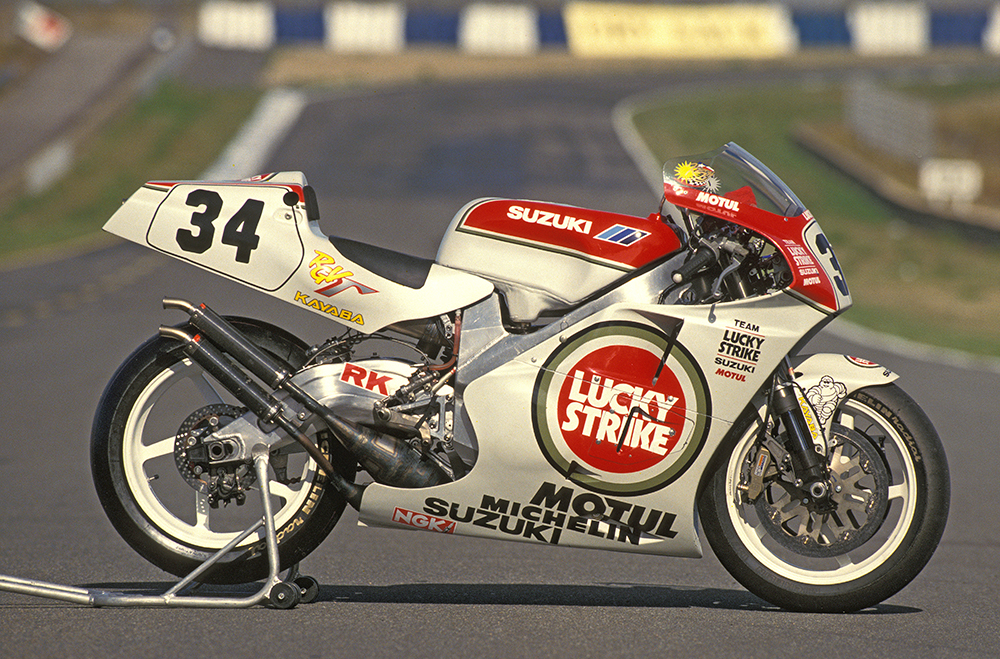

A user-friendly works 500? There’s a novel thought. And yet, Schwantz’s Suzuki was, relatively speaking, exactly that. Of the four rival factory racers I’d ridden in the previous four weeks, the Suzuki was recognisably the most refined and rideable. It didn’t have the raw top end power of the NSR500, but was a more confident, easier-handling bike, and a better package. The Cagiva, which so greatly resembled the Suzuki, ran it close, but wasn’t as easy to change direction with, and still lacked that edge in acceleration. And while the results obtained by Wayne Rainey and Luca Cadalora on the Yamahas spoke for themselves, the Yamaha didn’t have the top end power and appetite for revs the Suzuki had, even if it handled just as well.

By a patient process of gradual development, the Lucky Strike team and Suzuki engineers had evolved the RGV500 into a master of all trades. A bike that could win at the tight Eastern Creek at one extreme, and the fast Salzburgring at the other.

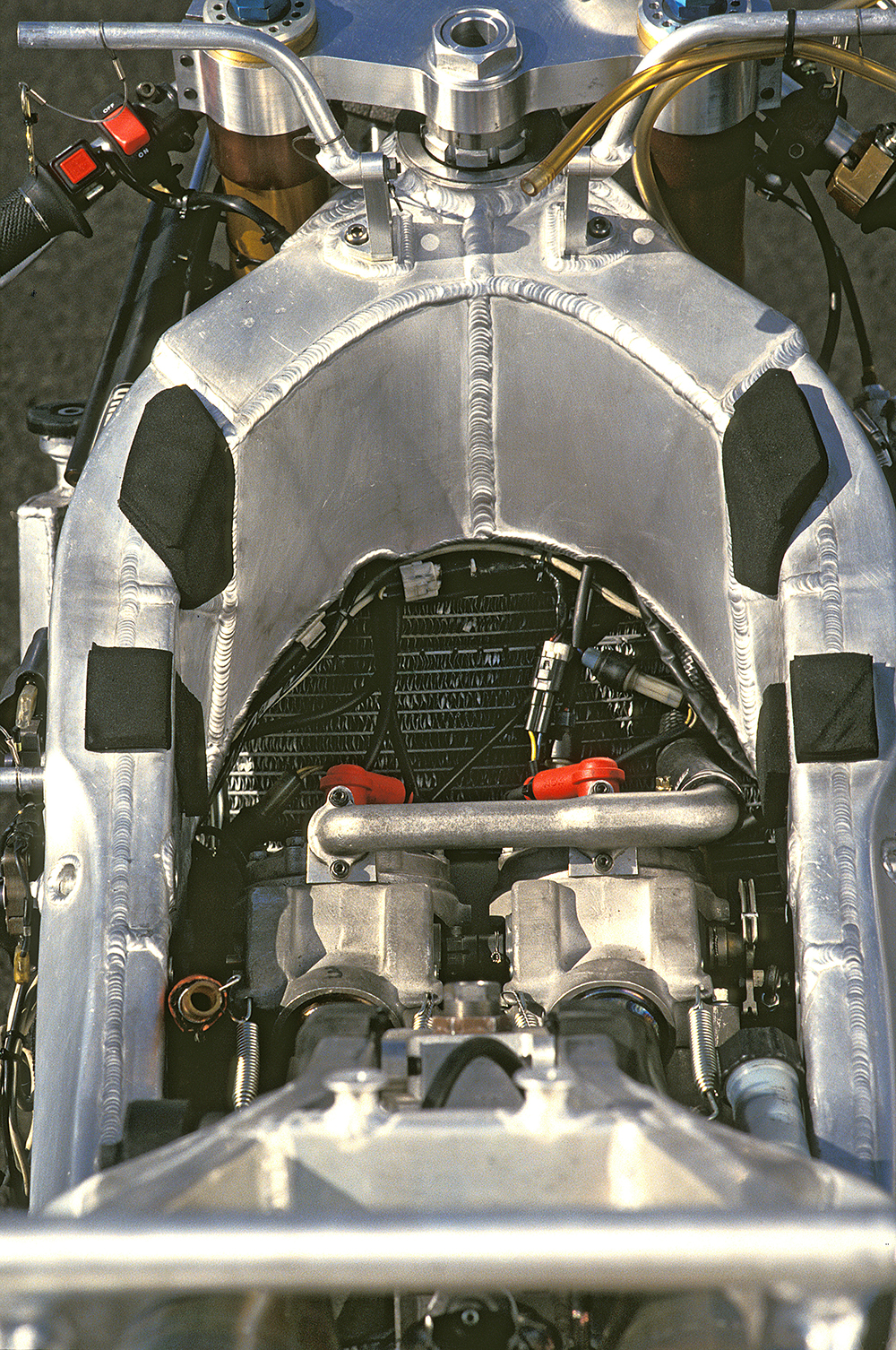

After riding it, the thought of an RGV500 roadbike based on Kev’ s world champion GP racer wasn’t as far-fetched as it sounds, and certainly more than a little tasty. I’d wind the throttle wide open in second gear exiting the last turn before the pits at Jerez, then feel the rear of the bike squat as the Michelin radial dug into the tarmac, the deep, throaty growl of the Big Bang motor, whose four cylinders fired in diagonal pairs (left front with right rear, then vice versa) just under 90 degrees apart, leaving over 270 degrees of down time for the tyre to get a grip on things and propel you without drama out of the turn and off down the straight at speeds you could only dream of, as you watched the tacho needle climb from under seven grand up to 13,600 rpm in seamless, stepless, glitch-free mode.

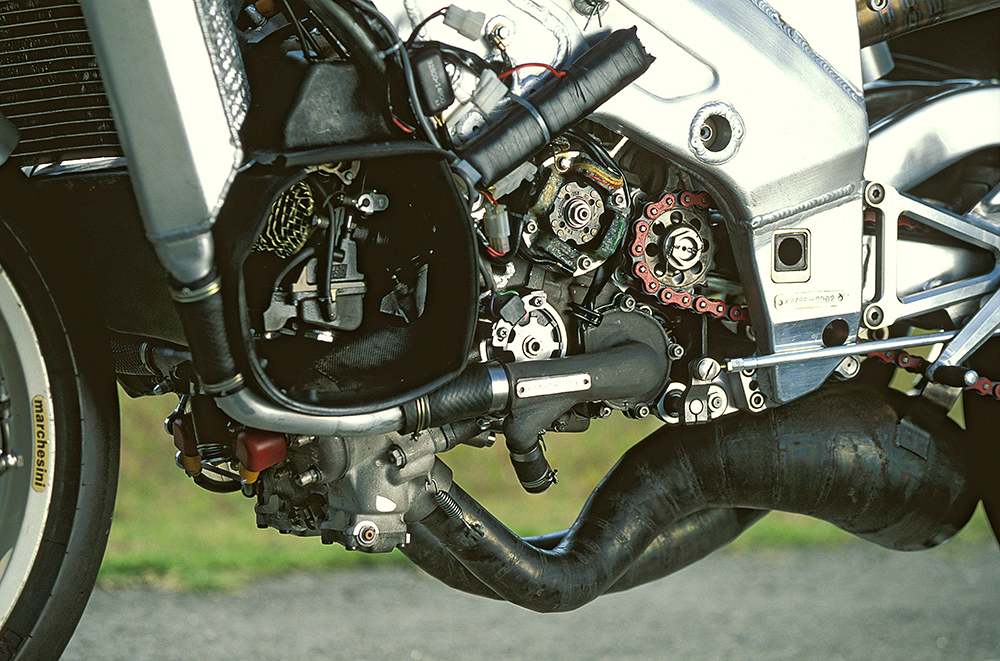

A suite of electronics made this possible, two of them a single guillotine-type power valve in the eight-port (five transfer/three exhaust) cylinders, and a complimentary Power Chamber variable-dimension exhaust system, each with a separate motor but working in unison according to the throttle position, ignition curve and gear selected.

I couldn’t tell when the power valve was wide open or the Power Chamber in full power mode, so smooth and linear was the transition, yet at the same time so strong and meaty the power output. Suzuki started the year with two different engine specifications, one sharper and more hard-edged, the other smoother and easier to ride, with the same absolute top end power. It’s a mark of the effectiveness of Suzuki’s work that both riders ended up using the more linear, more measured configuration for the last four or five races.

“I usually come out of a turn at around 8500-9000rpm,” said a watching Alex Barros.

“But the engine’s so responsive low down, you can gas it wide open from as low as 6500 revs, and it still accelerates well. You’re using too low a gear and too many revs out of the last turn here, which is why the bike’s standing on the back wheel.”

Barros’s advice of riding the torque curve out of turns proved a hot tip – but it still didn’t keep the front wheel on the ground, since the Suzuki was so potent it’d powerwheelie in third gear. Though peak power of “more than 165hp at the back wheel” was delivered at 12,800rpm, it would run almost 1000rpm over that, if you needed to save a couple of gearchanges.

And with Suzuki’s so-called pre-emptive traction control in the bottom three gears, allied to the benefits of Big Bang engine design, you can catapult yourself out of turns with reserves of power without the bike getting out of shape or the rear wheel going walkabout.

The Suzuki’s not-a-traction-control system retarded the ignition in the bottom three gears, depending on gear selected, throttle position and engine revs, and could be pre-programmed to deliver variable engine characteristics to maximise traction and grip under acceleration.

With all this computerisation, it was almost a surprise that the Suzuki still ran the same 36mm Mikuni dual-body flat-slide carbs as before, rather than electronic fuel injection like Honda was experimenting with. But even the Mikunis were trick; these had two electronic powerjets rather than the more commonplace single one, one for engine speeds up to about five-figure revs, the other to give an extra dose of gas over that.

“We first tested EFl with Wayne Gardner in Australia in 1989 on an NSR500, and they’re only just now getting it right,” Shenton said at the time.

Another electronic rider aid fitted for the first time that season was a powershifter, which was considerably more sophisticated than the systems then used by Cagiva, Aprilia and others.

The Suzuki system not only delivered an extremely precise, positive change, it even worked well if you short-shifted wide-open, which is more than I can say for the rival systems I tried.

Not only did the Suzuki system utilise a different length of ignition cutout depending on the ratio about to be selected, it was adjustable and also compensated for wheelspin. And it worked really well, and was reliable.

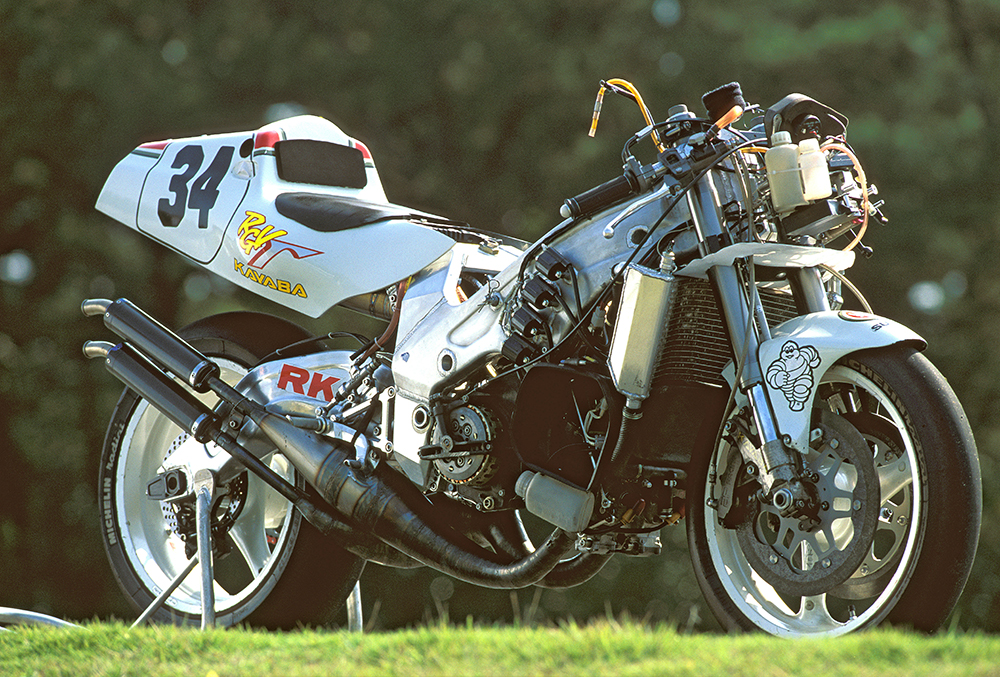

The Suzuki’s chassis was very similar to the previous year’s XR78 design, but Shenton admitted he experimented with engine position, mainly to improve the balance of the bike, as well as grip. The result felt more delicate to ride than the other 500s, as well as better-steering than the XR78 I rode the previous year. There felt to be more weight on the front wheel compared to the ’92 bike, which may have been a function of how it was set up, or more likely that they’d moved the engine forward relative to the wheelbase.

The Suzuki definitely changed direction better than its rivals, and had very neutral steering. With the ultra-responsive engine and perfect carburation, it was an easy bike to hold on line, too, and the Kayaba suspension was beyond criticism at the speeds I was riding at and on a smooth track like Jerez.

And the brakes? Well, the year before I’d got myself into trouble with the Suzuki GP team by saying that the AP carbon brakes fitted to Schwantz’s bike didn’t work well – and nor did they with anyone else’s hand on the lever other than the hardest braker in the west, Revvin’ Kevin. The team had fitted the bike I was riding with softer Barros-spec pads and discs, and I guess they proved I’d had a point, because they worked very well! Even though my disc temperature was 170°C down on Barros’s (380°C vs 550°C), the black brakes gave magical stopping power at the end of the straight, yet with lots of sensitivity if you just caressed the lever. Once hot (or luke-warm in my case) they stayed hot and delivered a constant lever pressure.

But that wasn’t all. Though not yet raced, Suzuki was testing the latest version of AP’s carbon clutch at Jerez, and left it on the bike when I rode it. This had been around the bike world since 1990, since it was tested by Cagiva and the Roberts Yamaha team. Though more expensive up front than a metal clutch, it was cheaper to use in the long run because of its durability, and saved a kilogram by fitting it compared to the steel 19-plate design. Like brakes of the same material, once hot, it worked really well, with a light action and no grabbing off the line.

Black clutch or not, Schwantz and the RGV500 were the class of the pack in 1993, a worthy champion aboard a world-beating motorcycle. Too bad we never got the road version!

Specs

Engine

Capacity 499cc

Type 70º V4 two-stroke,

reed-valve

Bore & stroke 56mm x 50.7mm

Compression ratio Not given

Cooling Water-cooled

Fueling 4 x 36mm Mikuni carburettors

Transmission Six-speed, extractable

Clutch Dry, multi-plate

Final drive Chain

Performance

Power Over 165hp @ 12,800 rpm (claimed)

Torque Not given

Top speed 324km/h (measured)

Fuel consumption Not given

electronics

Type Suzuki

Rider aides Electronic power valve and electronically-controlled variable-dimension exhaust system

Chassis

Frame material Aluminium

Frame type Twin-spar

Rake 23º (+/- 1°40’)

Trail 89-104mm

Wheelbase 1400mm

suspension

Type Kayaba

Front: USD 43mm fork, fully-adjustable, travel unknown

Rear: Lateral monoshock, fully adjustable, travel unknown

wheels & brakes

Wheels Marchesini

Front: 3.50 x 17 Rear: 6.0 x 17

Tyres Michelin

Front: 120/60-17

Rear: 180/67-17

Brakes AP/Nissin

Front: 2 x 320mm carbon discs,

six-piston AP calipers

Rear: Single 210mm steel disc,

twin-piston Nissin caliper

dimensions

Weight 130kg (Claimed, oil & water, no fuel)

Seat height Not given

Width Not given

Height Not given

Length Not given

Ground clearance Not given

Fuel capacity 24L

servicing & warranty

Servicing

First: Not applicable

Minor: Not applicable

Major: Not applicable

Warranty: Not applicable

business end

Price Not applicable

Colour Lucky Strike

Contact

Suzuki Motor Corporation, Hamamatsu, Japan