There’s a valid case for stating that the Ducati Monster is the single most important motorcycle to be produced anywhere in the world since the original Honda Super Cub debuted back in 1958. Ducati has manufactured over 300,000 Monsters to date, compared to the 100 million Cubs, but this motorcycle is not only the best-selling Ducati model ever, it’s also the one that saved the Italian manufacturer from going bust in the 1990s. It proved to be the crucial lifeline for the Bologna factory in allowing it to survive long enough to be purchased in 1996 by American investors TPG, and set on the path to its present success as part of the VW Group.

In 1999, the M600 midi-Monster variant was the best-selling motorcycle of any kind in Italy – the first time any Ducati had ever achieved such status. And in 2001 the debut of the S4 Monster, powered by the 916 Superbike’s desmoquattro engine, opened the door to a new, more performance-conscious naked bike market. Building on the model’s cult status as a two-wheeled icon, the plethora of different Monster derivatives built to date have, in some years, represented over 70 per cent of Ducati’s total production. But, more to the point, it’s been the most-copied motorcycle ever produced by an Italian manufacturer, rivalling BMW’s GS family in establishing a new style of bike whose commercial success invited instant imitation.

“I was born in Buenos Aires in 1959 and grew up in the Beatles era, hoping to be a musician. At eight I dreamed of being the Argentinian Ringo Starr and wanted a drum kit for my birthday. My brother and I are exactly one year apart, always had joint birthdays. Together we got a 50cc Kreidler Florett motorcycle from one of my uncles, which I didn’t really appreciate because I really wanted a drum set! But we soon learnt to ride it, and after that it was bikes, not music.

“I saw On Any Sunday when I was 12 years old. I went so many times that the guy at the cinema would let me in free! The sight of Malcolm Smith and Steve McQueen riding in the desert was paradise, but it was something we could only dream of doing because we didn’t have such bikes. Back then in Argentina our nationalised industries were protected, so the importation of foreign bikes was forbidden. People would smuggle Husqvarnas and Suzukis in from Uruguay or Paraguay. I remember seeing a Honda Elsinore that somebody had brought in from Chile – it made me think of that movie!

“While visiting our uncle in USA in 1976, my brother and I bought a Suzuki RM250 motocrosser to ship to Argentina, and we took turns to race it. I did okay in motocross, but I had a big crash in ’78 and I hit my head very hard – I stayed unconscious for 24 hours, but recovered. But I stopped racing, because I had to do my Military service.

“I’m a big guy, so I was the bodyguard for the Press Chief of the Argentinian Navy, which meant a lot of sitting around. To pass the time I’d always be drawing motorcycles and cars – I love drawing – I got bad grades at school because I’d be drawing bikes instead!

“In 1979 I finished my Military service, I was 19 and I wanted to study Mechanical Engineering to help make my drawings become real, so I signed at Miami University. Then I discovered Industrial Design, so transferred and did a couple of motorcycle projects, plus a scooter. After graduating I tried to get a job with Yamaha or Honda, who both had design studios in California – but they couldn’t hire me since I wasn’t American. So my first job was with General Motors at Rüsselsheim, and that’s how I ended up in bikes.

“Anyway, I told my boss that I wasn’t going to stay because I really want to work on motorcycles, he knew some people in Honda Germany, so I got in touch with them. At that time, Mr Honda was still alive and they had a project to open a studio in Milan, because his dream was to have a studio in Italy to focus on future mass mobility. So they offered me a job. I met some great people, like Hitoshi Ikeda, the designer of the CB750 K0, but the first thing I did when I came to Milan was to buy a Ducati! I found a dealer with this silver and red 750SS for 7.5m Lira ($6300), which was a lot of money, but I said, if I don’t do it now, I never will.

“I remember riding it to Honda for the first time and Mr Ikeda came to my desk and asked me why I didn’t buy a Honda. I said because I like Ducatis. He told me to go with him and I thought ‘oh man, I’m in trouble’. We went to the parking lot and he put the key in and started the engine and suddenly his face changed. He went vroom, vroom, with the throttle and then he turned to me and said, ‘you know what, this bike has a heart. We Japanese are never going to be able to make something like this.’ And from then on every time he’d visit the office he’d take the key to start the Ducati, blip the throttle, and then come back with a huge smile!”

“I remember very well the first project I was given. I was sent to Barcelona to just walk around and look, and talk to people. There were a lot of noisy Derbi and Montesa two-strokes and suchlike, but everyone who could afford a motorcycle had one – this was their basic transport. I did a lot of sketching there with one of my Japanese colleagues and then we came back and did a project called ‘Future Mobility for Honda’. Our boss took them to Japan and when he came back, he said they didn’t like anything and that we were really bad.

“Then in November 1987 came the Tokyo Motor Show, the following month in Milan we got a Japanese magazine and on the cover we saw Honda’s interpretations of two-wheeled personal transportation – and of the eight or nine proposals, three of them were ours! I went to my boss and asked what happened, and he said they were all done in Japan. I said no, we did those sketches right here. Then I realised that everything must be seen to come from Japan. I was really mad, so I decided to leave – how could I ever progress if my designs were being claimed to be done by someone else?

“I left Milan in thick fog, then halfway to Varese the sun broke through, and the sky was bright and clear. In Claudio Castiglioni’s office, before I even sat down, I said ‘it’s so beautiful I’m ready to come and work here right now! He laughed a lot. We talked for an hour and a half about this bike and that, and then he said ‘I’m going to give you a job’.

“While I was working at Honda, we used to receive magazines and one arrived with pictures of the first 851 Ducati stripped naked. They’d simply removed the bodywork in order to take the side-on shots. I made an A3 colour photocopy and said to myself, this is the bike I want to make – it’s what I’d like to ride myself. Forget about all the race bodywork and stuff that is completely pointless on the street. I want to build this bike just as it is.”

“I remember meeting the boss of Ducati, Massimo Bordi. He was a bit scary, but I tried to convince him we needed to do this naked bike. I drew him sketches of it and he said, ‘okay, one day, but here’s something else you must do first. Each time he came, I tried to remind him about the naked bike idea. But it was, ‘Okay, Galluzzi. Nice idea, but don’t bother me now with that, please’.

“But I was young and really tenacious, so in 1990 it was summer, and at that time we stopped for the whole month of August. So I asked him since I was going on vacation, can I get some parts so I can draw some sketches? He said yes – I think he really wanted to get rid of me, so he said to go to Ducati and get whatever I wanted. That August, Claudio Castiglioni lent me his new 888 Strada, the first red desmoquattro with the 17-inch wheels, because I had my mother-in-law living in France and my wife and kids went to stay with her. I would ride back and forth on the 851 to spend the weekends with them, so I was able to ride it quite a lot, and I realised it had a great engine that could really be the basis of the bike I wanted to build.

“So I got an 851 frame, thinking I could use the liquid-cooled eight-valve engine. But the 888 had just reached production so it was back ordered, and anyway it was too expensive. But the 900SS wasn’t selling very well, so there were ready supplies of its air-cooled desmodue motor, and not having a radiator was a good thing. I decided to use the desmodue motor with the 851 frame that had a rear suspension link, not cantilever like on the 900SS.

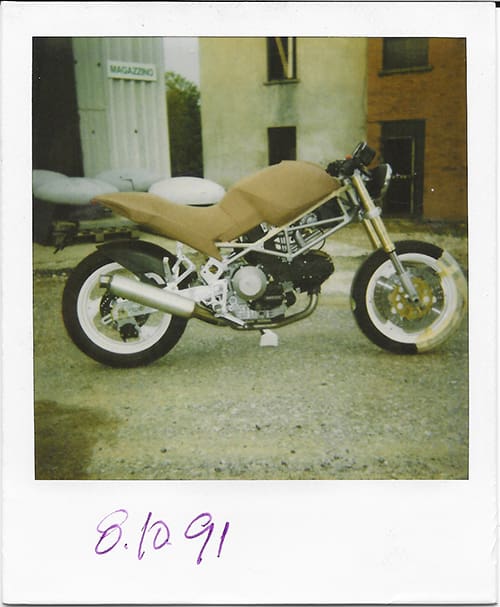

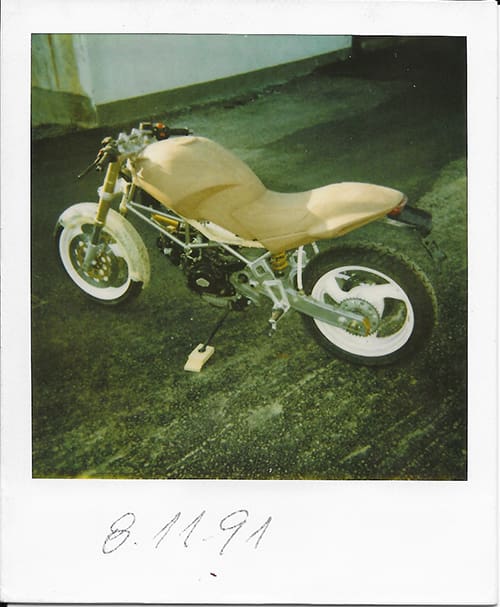

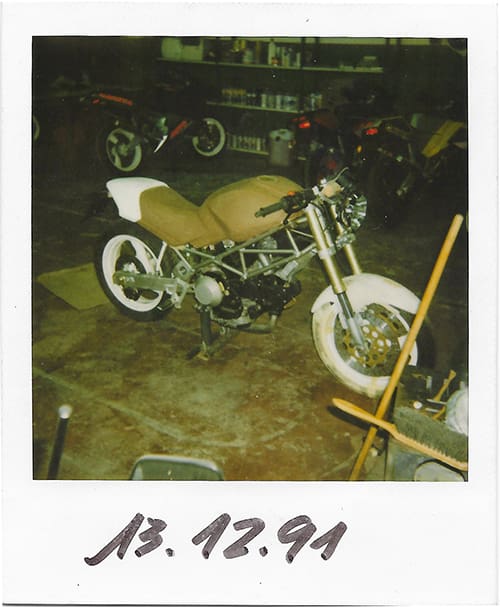

“I started building the bike, but I needed help, so I asked them to lend me Fabio Montanari, the guy at Cagiva who used to hand make aluminium tanks for the Paris-Dakar bikes. Because he’d make a lot of noise he was given a small shed in the factory grounds beside the lake, away from the main design studio in Morrazzone. Without anybody knowing we brought the bike there to build it, it was a secret, because I was supposed to be at Morrazzone and out of the picture.

“But one day Bordi realised where I was, because during that period he wanted to do a new Paso sports touring bike, which he always thought Ducati should have. So he assigned Pierre Terblanche to do this, and one day a big discussion started in Claudio Castiglioni’s office about the investment needed to do the new Paso. Claudio apparently asked what I was doing down by the lake and how much is it costing? So suddenly they opened the door of the shed, and we were there working on the Monster. It wasn’t properly finished, but was pretty much complete.

“Fabio and me, we pulled the bike out into the open and I wish I’d had a camera, because I still remember the look on people’s faces! I remember Claudio touching the seat and saying, ‘Is this it?

Are we missing something here? Or is this finished?’ I said, ‘No, that’s it.’ They started having a discussion about it there and then but, with Bordi pushing hard for the Paso, they decided to do it first, which meant big money. We finished the naked prototype and put it to one side.

“Then towards the end of 1991, somebody told me they were having this big meeting of Cagiva importers. I convinced Claudio to bring the bike into the meeting and the Cagiva importer for France, Marcel Seurat, was there, plus Germany was there, England, all the big ones. The meeting lasted for three days and on the last day Claudio said, ‘We have something to show you, and we’d like to ask your opinion.’ We took them into a big room, removed the cover, and everybody was like – ‘Wow, what is this??! The guy who reacted quickest was Seurat – he said, ‘Claudio, we’ve got a winner here. Let’s get this thing going – I’ll buy the first 1000 bikes!’

“That was when they invented the story of how everybody said, ‘where is the bodywork? This looks like a Monster!’ But nothing happened like that. On the contrary it was ‘what do we do with this weird thing?’ Only Seurat understood it and pushed hard for the bike. But Claudio got it completely – he had a fantastic appreciation of what his customers wanted. He’d stop by two or three times a week to look at what we were doing, and to sit down and discuss it with us, and throw out new ideas.

“That’s why I spent almost 19 years with him. He understood design very well. We had big arguments – but that was all part of being so passionate about it, and that’s what drove the creative process we had in Cagiva.”

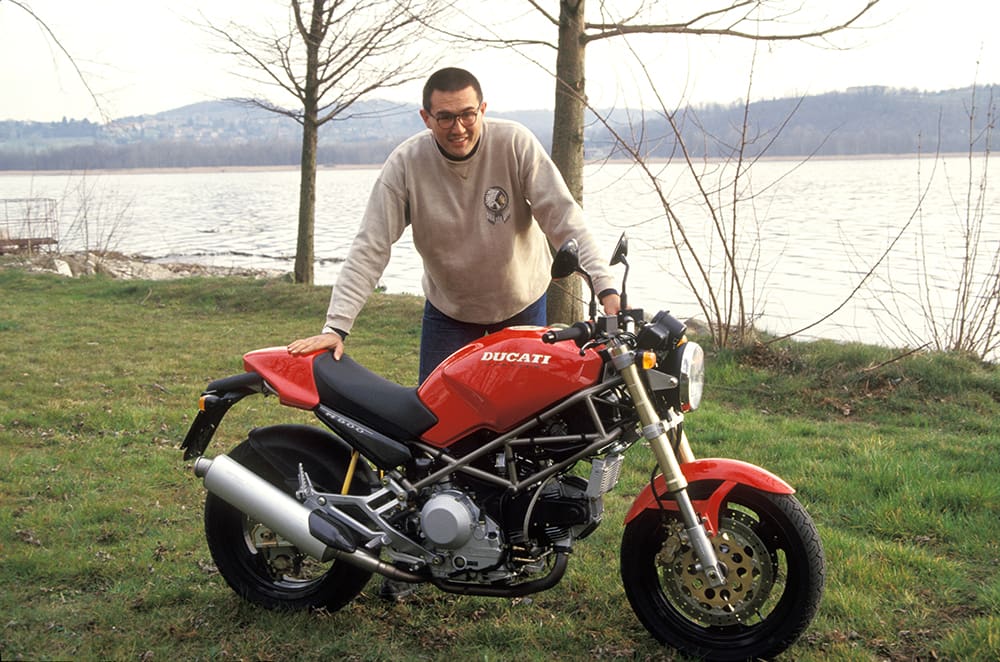

“So we launched the bike officially at the Cologne Show in October ’92 and to say it was a hit was an understatement – it just took off – so all the other importers increased their orders.

“I heard many stories about why we called it the Monster, most completely untrue! The real reason is because I was spending hours on a design that didn’t have a project number, the financial controller needed a name to which to allocate the costs. Around that time, they had a craze in Italy called ‘Monster in My Pocket’ for young kids to collect. There were about 300 different rubber monsters, and each night my two sons would ask me ‘Dad, did you buy us a monster? Monster, monster, monster?’ And each weekend we’d go to the store to buy three or four boxes of them to add to their collection. So I said ‘why don’t we call it the Monster?’ So Monster it became – never the Italian word, which is Mostro, because that’s not what it said on the boxes.

“It’s also not true that it was originally going to be called the Cagiva Monster – it was always going to be a Ducati. But the first prototype they made in Bologna for the test riders to use was painted green, so they called it Kermit. It was a deliberate insult because they didn’t like it since it wasn’t a sportsbike, and Farnè [Ducati’s technical guru] fitted a chopper-style handlebar to it and a custom exhaust. I complained and they eventually changed it back, but the irony is it saved Ducati, and allowed them to keep on building title-winning Superbikes and MotoGP racers.

“The spirit of the Monster was born on the Los Angeles Crest Highway in 1984, because we were going to school in Pasadena, and that was the road we used to go back and forth along to get there. It was easy to crash, because the bikes and tyres were crap, and repairing bodywork was difficult and expensive. Plus, we had a friend who had an old Triumph Bonneville, and he would always keep up with us on the four-cylinder Japanese sportbikes, and even sometimes beat us to the Rock Store on Mulholland where we’d meet at weekends.

“Back then I had a Suzuki GS750ES with 16-inch wheels and everything, and still he’d always be there. Then the first Honda Interceptor and GSX-R750 came out, everything got complicated and expensive and I ended up working for Honda, designing so much plastic – but what for?

“I want to enjoy my ride. Can I go fast? Maybe, but I need to enjoy it. And to do that I only need one engine, two wheels, a tank, a handlebar and some metal to join them together.

And that’s how I created a monster.”

Words Alan Cathcart Photography AC archives