Four decades ago 500cc grand prix bikes started making a lot of power, so tyres got bigger and frames got stiffer. Chasing more horsepower was no longer the biggest deal in motorcycle racing. That’s why 500 chassis of the early 1980s are a million miles from today’s ultra-high-tech MotoGP creations; most especially Suzuki’s GSX-RR, the best-handling bike on the grid.

Chassis geometry has been refined, mass-centralisation has been improved, machine balance has been perfected and chassis flex has been developed to improve performance while cornering with sometimes more than 60 degrees of lean angle. All these improvements have been demanded by more horsepower, much grippier tyres and far fiercer brakes.

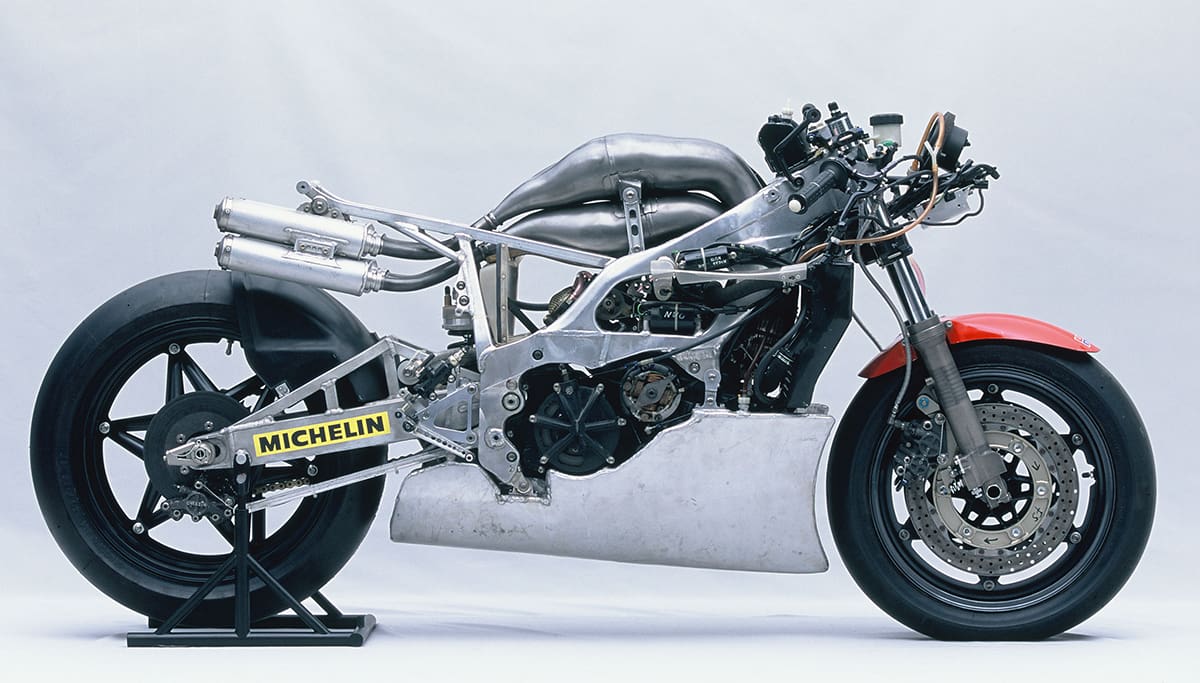

Chassis flex is arguably the most fascinating area of cornering technology, because engineers have to design the frame, swingarm, fork, triple clamps and ancillaries that provide lots of longitudinal stiffness for braking stability, much less lateral stiffness to help the bike track the road surface at high lean angles (when the suspension doesn’t really work) and the right amount of torsional (twist) stiffness to provide both stability and feel when the rider spins the rear tyre out of corners.

In theory, these three facets of flex should be mutually exclusive, but the job of the engineer is to make the impossible possible. Ultimately they want to make the bike bend in the corner, to create an element of self-steering. It’s a very complex science.

Alex Baumgartel of Kalex, the most successful chassis designer in MotoGP, and Mats Larsson who has worked with Öhlins since the early 1980s talks us through it.

Check out the current issue of AMCN for the full story.