Every rider has a bike they wish they still owned. Maybe it was sold in a moment of weakness. Maybe it was stolen. Maybe it was lost in a silly bloody wager. Either way, the regret is real and the story’s usually a cracker…

What do a purple Suzuki GT750, a learner-legal Yamaha RD125, a Harley Heritage Softail and a Norton 750 Interstate have in common? They’re bikes AMCN contributors once owned, then watched disappear… and have been quietly grieving ever since.

Some were sold to pay for something more sensible. Others were victims of theft, mechanical drama or general life derailment. One was swapped out of a sheer tantrum. Others might’ve been let go purely so its owner could go on to buy it back, which he did… on five occasions.

For Ben Purvis, it was the clapped-out Honda NC30 he repaired with some cheap, blind hope before chasing a magazine job on it. Gordon Ritchie rode his Yamaha RD125LC the long way from Glasgow to the Isle of Man TT on L-plates, got cleaned up by a Volkswagen, crashed it again an hour later and still calls it the best bike he’s ever owned. But can anything beat the mixed emotions Roothy must have about his decision to buy a Norton instead of the property that’s now worth $1.6m? Most definitely.

Because here’s the thing: it doesn’t matter whether a bike was rare, powerful, beautiful or complete rubbish. If it meant something to you, it can so often mean something more than money. So we asked a bunch of familiar faces to tell us about the one that got away. And not just what it was, but why it mattered. These are their stories. And regret has never been so entertaining.

John Rooth

Norton Commando 750 Interstate

In 1974 I had enough money to buy a fisherman’s cottage on the mudflats in Wynnum, Brisbane. I know that because my prospective father-in-law told me several times. So I bought a secondhand 750 Norton Interstate and left town instead.

It was superb, thundering power in a lightweight package that handled and a huge step up from my Matchless 500 and the ratty Honda 450 I rode out of town. It was everything I’d dreamt while looking at those Norton ads in Two Wheels under the desk in high school. But after hauling it home in the ute twice with seized engines that cost months of downtime and every dollar I had, I spat the dummy.

So I sold it to a mate and spent the next 50 years trying to buy it back. It was everything I wanted in a bike, I just had to learn how to keep it on the road. Finally I realised he’d never sell it so I bought a 1972 Norton Roadster to ride and an 850 Interstate to restore. I sold that original Norton for $500 and it’s cost maybe $40k so far in placebos. Meanwhile, the shack on the mudflats that was worth $5000 back then just sold for $1.6m.

Basically, buying that bike and riding out of town kickstarted my life into a kaleidoscope of motorcycles, freedom and adventures. I don’t need it back; I just need to remember the lessons it taught me. Turns out all I’ve ever wanted is a motorcycling life.

Life isn’t about where you’re going, it’s about how you get there.

Mick Matheson

Harley-Davidson Heritage Softail Classic

The one I miss, my 1994 Harley-Davidson Heritage Softail Classic, didn’t get away. It was taken away – stolen from the garage while I slept. It’s one of two bikes I’ve lost to thieves and I miss them both, much more than I miss the ones I voluntarily parted with. I guess that’s because when I’ve sold a bike, it’s because I was no longer in love with it.

The other one that was stolen, by the way, was a 1975 Honda Gold Wing, but I had it for only a couple of weeks. Because of that fleeting ownership, I think I miss the idea of it more than I miss the experience of it. I never had the chance to get to know it well.

But the Harley; I knew it very well. We lapped Tasmania and did other interstate trips as well as undertaking tons of local journeys. I had no shortage of test bikes to ride in those days, but I preferred to take the Hog when I had the choice. I even took it on backroad dirt rides with BMW GSs and Yamaha Teneres. There was me in a Brando jacket and open-face helmet annoying the hell out of my dressed-for-adventure mates by keeping up with them.

The Softail just worked for me. It was comfortable, cruisy yet surprisingly capable – more capable than it ever got credit for, despite it being about the lowest, fattest and most compromised of all Harley’s designs.

I just knew how to extract all its potential. Maybe that’s one reason I was so fond of it; it’s like we shared a secret.

In one short year and 20,000km, it didn’t show any signs of suffering because of what we did. It was a tough, simple, old-fashioned machine; very much a 50-year-old motorcycle with modern reliability and strength, and I loved that.

The beauty of today’s secondhand bike market is that I could have another one now. And a Gold Wing, too. But I won’t, perhaps my tastes have moved on. But as much as I miss the Softail, I’m content to wallow in the melancholic memory of what I once had.

Ben Purvis

Honda VFR400R

It’s got to be my old Honda VFR400R (NC30). It was a 1989 model, imported from Japan to the UK secondhand sometime in the early 90s, and I must have bought it in late 1995, just after getting my licence. It was my first ‘big’ bike.

I rode it all over the place and commuted on it in all weathers. One harrowing ride down some country lanes returning home from law school in deep snow after an unexpected blizzard still sticks in the mind…

Later I had what was probably quite a spectacular crash on it. The damage showed it landed upside-down on its tail first, crunching the subframe as well as every body panel.

I repaired it myself (badly) with the cheapest knock-off parts I could lay my hands on. Its first run after that was up to an interview at Performance Bikes magazine, including a very sketchy assessment ride with the then-editor, trying to keep up with his Suzuki TL1000 while the knowledge of my untested repair work gnawed away at the back of my mind. Didn’t get the job…

By the end of 1997 I was working at MCN, with the access to test bikes that came with that job. Since the NC30 had developed an unnerving habit of jumping into false neutrals when hard on the throttle – not ideal when overtaking in the face of oncoming traffic – it got consigned to the back of the garage for a few months before I sold it, for little more than scrap value, to a neighbour sometime in 1998.

Would I want it back? It was pretty knackered when I sold it and I can’t imagine another 27 years has improved it much, but another, minty-fresh NC30 in the same HRC colours as my original would certainly be worth a corner in my (sadly purely theoretical) dream garage.

Gordon Ritchie

Yamaha RD 125LC

The bike I would most like to have back in my possession – to actually ride – is my Yamaha 350 YPVS. Or maybe it would be any of the three different Yamahas I attempted to “race” at one stage? But the bike I most regret selling was my first “long-term” learner bike (I’d smashed up the previous Suzuki GP 100 and Yamaha DT125MX in relatively short order…).

My white Yamaha RD125LC (restricted for learners by law) came to me via a friend who had just passed his test and was moving up and I think it was bog stock.

The biggest modification was a Dream Machine paint job, done as an insurance repair after I was knocked off of it going the “wrong” way at the 33rd milestone, while heading to Guthrie’s memorial to spectate at the IoM TT. Long story, but I was punted skywards from behind by an Isle of Man commuter in a Volkswagen Variant just as the roads were about to close for evening practice. No, that delay in 1980-something TT qualifying schedule wasn’t weather-related, it was due to a sideswiped RD 125LC and its slightly addled rider being escorted back down to the Creg Ny Baa hotel by a kind (if exasperated) sergeant in a big old “Roads Closed!” sweeper cop car.

The front of the bike was all misaligned; the handlebars, top and bottom yokes and front wheel no longer in any symmetrical relationship. Which is why I crashed it again an hour or so later, right on the Douglas prom on my way back to my B&B.

A car had pulled out in front of me and I instinctively straightened the ‘bars as I braked hard… which of course my misaligned front tyre took exception to… and instantly let go.

On the off chance you were one of the many leather-clad drunks standing on the steps of the hotel opposite who cheered, jeered and gave poor little learner me various wanker signs, the distant past has just been in contact to tell you to go and get f**ked.

I loved my wee LC so much, sometimes I would just take the long way home from work to ride it in the hills and B-roads behind my hometown. Even a few times I rode to and about astoundingly beautiful places like Loch Lomond, because I could. I also went exploring greater Scotland on that wee LC, still on L-plates, right up into the far Highlands.

The wee bike did about 70-75mph flat out, but freedom and giggles feel the same at any velocity. Of course, I had to sell it after passing my test, simply to experience more cubes and higher speeds, and one bike at a time was a budgetary reality.

I only ever owned a few bikes of my own, but the LC – my gateway drug to a life of engines sandwiched between two wheels – is the one I most wish I’d kept.

Guy ‘Guido’ Allen

Kawasaki ZRX1200R

Working out which bike you most regret selling is potentially a heart-rending and arduous process. Luckily for Muggins, it’s not – all you have to do is look at my online search history.

Over recent years I’ve been a serial offender when it comes to buying back models I once saw off the property, only to admit that it was a silly bloody idea and go hunting for another.

I’ve been fortunate to run a bit of a fleet over recent decades and, every now and then, spit the dummy over the burden of keeping them all going and then conduct a mass cull. Sometimes it goes a bit too far.

As a result, I’ve ended up tracking down whatever it was I missed. Often the ‘new’ iteration is better than the previous, so that’s a happy if expensive result. Some examples in my shed at the moment include a Ducati 916, Triumph Daytona 1200, Honda Valkyrie Interstate and a six-cylinder CBX1000.

Right now I’m most annoyed about selling my 2003 Kawasaki ZRX1200R. It was a long way from being a perfect example, but I love both the story behind the machine and what it does.

It’s effectively a latter-day Eddie Lawson replica (the original was the 1982 KZ1000R), though I’m sure Lawson never earned a cracker out of this model, which is a shame. He is one of my long-term racing heroes and a quiet achiever.

The Eddie connection and the bold looks were what did it for me when I tripped over it at Don Staffords’ modest emporium about a decade ago.

It was a delightful ride. Not the most powerful thing out there but it has 92kW (123 horses), which is more than enough to punt a naked bike at the horizon. Still running carburettors and a five-speed transmission, it has old-world charm while being a dead-reliable and quick ride. Plus it will tackle commuting to touring, or the odd thrash down a twisty bit of tarmac.

Sadly, it got caught up in one of my hissy-fit culls and quickly found a new home.

I’m pretty sure I need another, though good ones are hard to find. The owners are reluctant to let go and I completely understand why. One day someone will weaken and sell me their nice example, and probably regret it…

Micheal Scott

BMW R75/5

Given a career in which I have ridden exotica ranging from MV Agustas to the feet-first Quasar (the length of Britain), every Japanese superbike until the late 1980s, Ducatis galore, Heskeths, a Silk, hub-centre-steered eccentrics, Vincents and other post-vintage thoroughbreds, and had a personal novel-chassis Laverda Montjuic racer built to my own specification, this might seem a pedestrian choice.

Nothing comes close to my 1971 BMW R75/5. I bought it to ease a broken heart, sort of, after a romance turned sour. But also because I was sick of bad bikes: my Matchless 500 that used to leak oil onto its points any time you managed to get it to a halfway reasonable speed, my Triumph Bonneville, which was fun but had some nasty traits. Not least that it was a US-spec model built halfway through a factory changeover to metric. It had five different types of fastener – metric, BSF, AF (American Fine), plus old-school Whitworth and Cycle Thread – so you never could find a spanner to fit. Eventually every nut was rounded off.

The BMW taught me everything good about motorcycling. Firstly, that it could be more than just scatter-brained rebellious enthusiasm that made your knuckles bleed and kept you in the workshop. Or by the roadside. Secondly, that bikes could be built to logic as well as passion. Thirdly, that you didn’t need a dirt bike to travel ridiculously bad roads. And, finally, that I could make a career out of loving bikes.

It took me far and wide around southern Africa, including Lesotho, Namibia, Swaziland and Zimbabwe (still called Rhodesia then). And shared as a new romance turned out to be the real thing.

I sold it, reluctantly, because we emigrated from South Africa, at that time mired in stomach-churning apartheid. The BM was lost to me forever, but I sometimes dream of getting another one just the same. Its austere styling and pin-striped formality still strike a chord.

Alan Cathcart

Suzuki GT750J

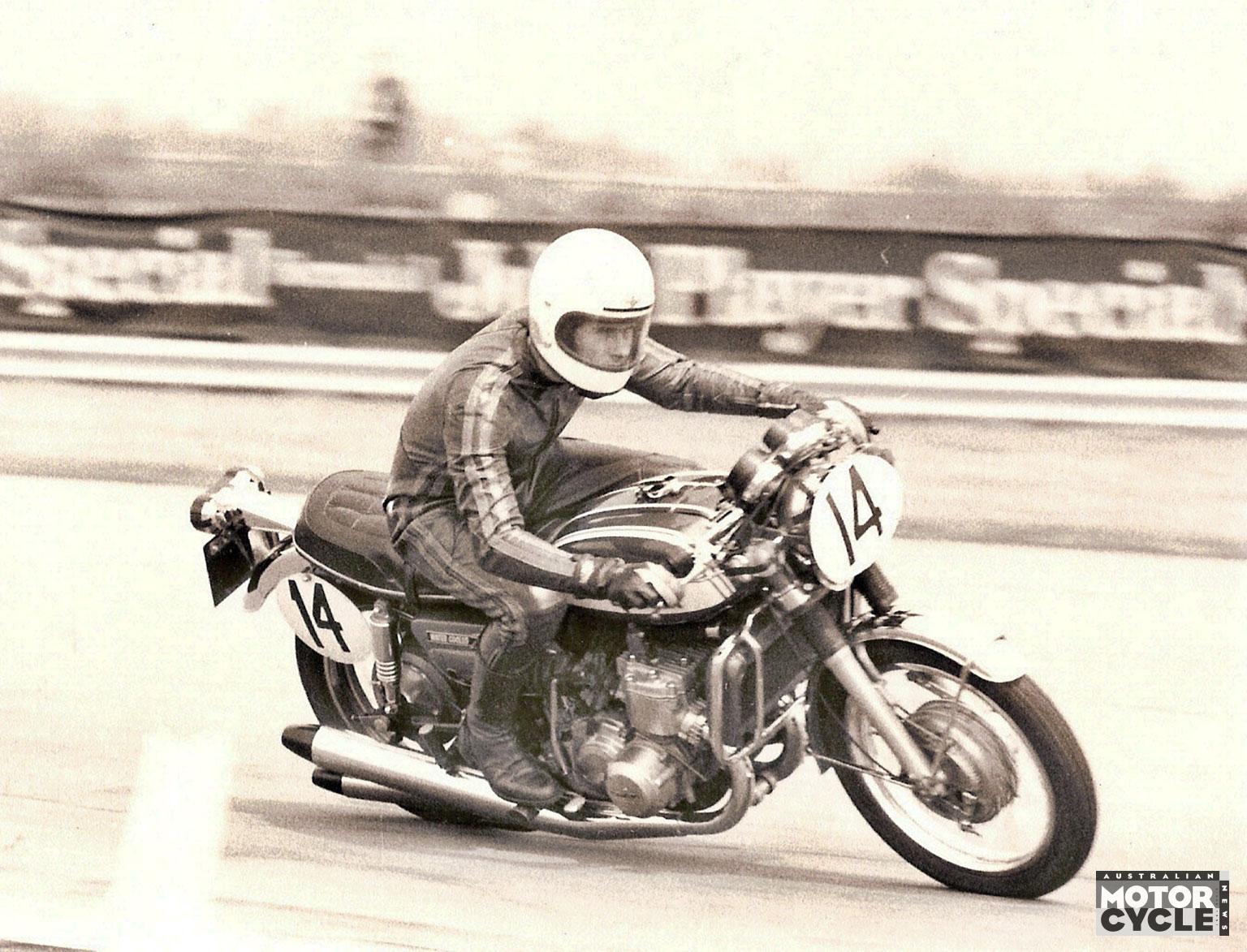

A Purple Peril of a Flying Kettle (the nickname it got in the UK; Water Buffalo is strictly a Yankee moniker) may seem an unlikely bike for those who know me to discover I ever owned, let alone shed a tear over its passing down the secondhand spiral. But the Suzuki GT750 J, resplendent in California Burgundy (as it was very appropriately named here in Britain) that I purchased brand new in 1972 is the bike I most wish I still had – as much for the improbability of beginning my 50-year road-racing career aboard it, as for the fact that my first bike with more than one cylinder and over 250cc in capacity wasn’t a desmo V-twin.

The Kettle was the bike I first took to the track on at the MCC’s Silverstone club races in July 1973, complete with a puny front drum brake, which meant I had no stoppers after four laps of the shorter 1.6 mile (2.5km) Club course, complete with two hard stops per lap for the bottom-gear hairpins at either end of the straight bisecting the British GP circuit. Oh, and did I tell you this was the first – and indeed last – two-stroke I owned? Complete with minimal engine braking to make up for those MIA drums front and rear? No wonder UK importers Heron Suzuki offered a free replacement of the front drum by twin front discs the following month.

By then I’d started my search for a Latin four-stroke with just a couple of cylinders to go racing with, which meant my Suzuki became the great all-rounder of a roadbike it was theoretically designed to be. I used it to commute to my travel-industry job in London’s West End, then for weekend jaunts with my new girlfriend Stella, later to become my wife. She still says she nearly didn’t come on our first date when she saw what I turned up on to take her to Wimbledon Speedway for a night of cinder racing. But parking the Suzuki on the footpath next to the entrance to the Hard Rock Cafe just off Piccadilly for supper afterwards swayed things in my favour – especially since, in between, she’d had her first high-speed fang on a motorcycle. It was the first of several we enjoyed together over the next five years, including touring on it through Europe.

So it was Suzy Suzuki wot swung it for me – and 47 years and three kids later, I wish I still had the Purple Peril in my garage…

Ken Young

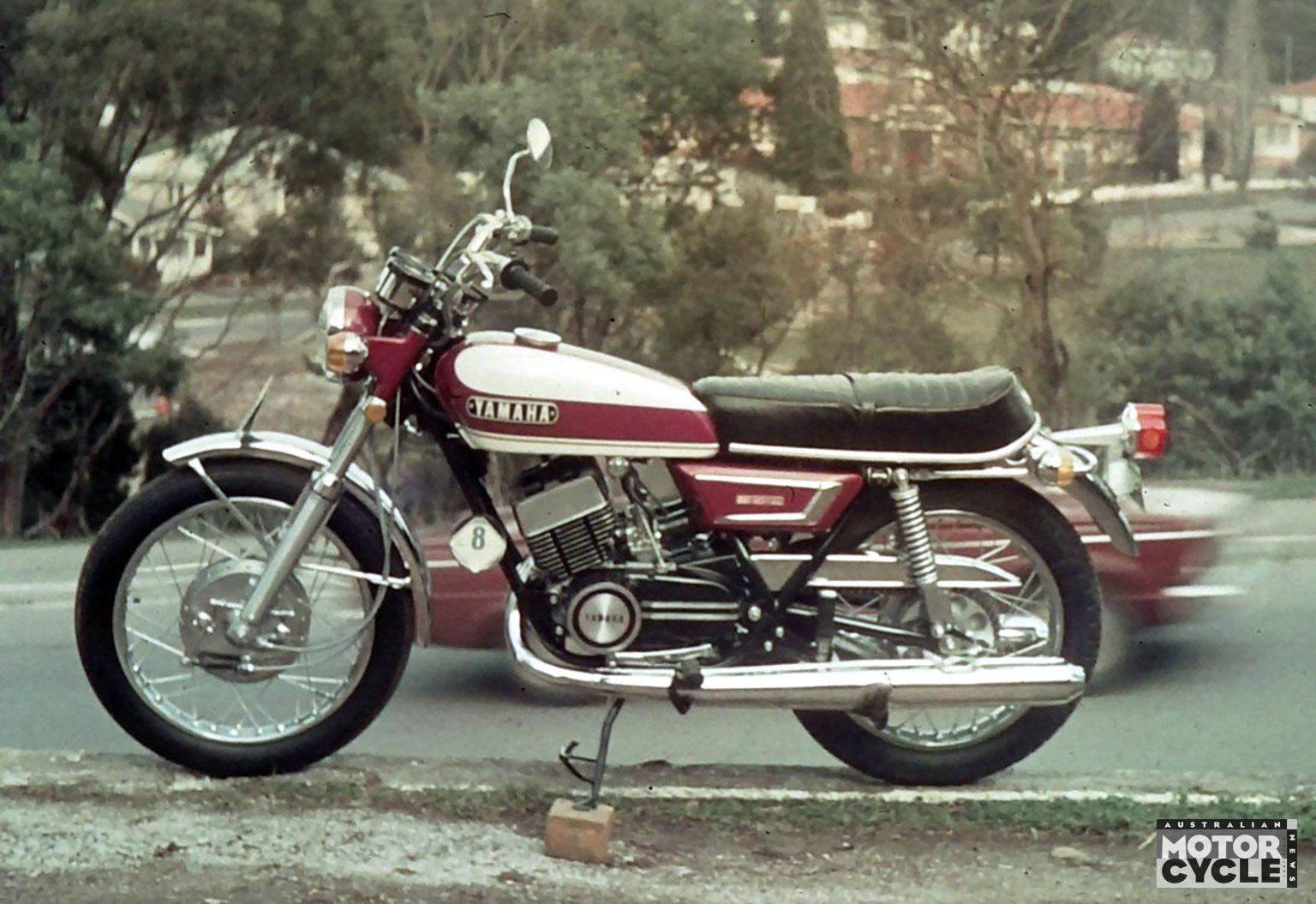

Yamaha R5 350

The first of anything always sticks with you, like my first bike, a 100cc Yamaha YL-1 twin. I learnt plenty on that little smoker: what a piston hole means, what seizing feels like and why you should never forget to refill the Autolube tank.

Next came a Honda CB350 with vacuum carbies that fell out of tune the moment you left town. Then a series of Yamaha RDs – 350s, a 400 – but the one that truly left its mark was the Yamaha R5 350. It was my first brand-new ‘motor car’ of a bike and one I had to spend time to actually run it in.

In Tasmania, that meant a hundred miles around town to get the feel of it, then taking it to show to everyone I thought was important, followed by a break-in loop the next weekend. From Launceston to Campbell Town via the straight and boring Midland Highway, then through the fast sweepers of Lake Leake Highway, ending with a stop at St Helens to make sure everything was in order. Then up through the tight sections of the East Coast Highway to Scottsdale, then flat-out over the Sideling and back to town for its pre-booked first service and decent rubber on Monday morning.

Powerful, light and reliable, it was my first new bike, my first racebike and the start of my long love affair with 350cc roadbikes. Each one felt better than the last, until the RD400, which was maybe slightly better again, but different to ride.

The Honda had its moments. The YL-1 taught me a few lessons, but the R5 was fast, exciting and reliable.