MotoGP’s pitlane commentator Simon Crafar bagged half a dozen laps on Pecco Bagnaia’s Ducati Desmosedici GP22 around the Misano Circuit.

![]()

I’ve known Ducati’s Sporting Director Paolo Ciabatti and team boss Davide Tardozzi for literally decades. Tardozzi was one of the original heroes of WorldSBK when I was a young racer, and then when I became a WorldSBK rider he was a team manager for riders I raced against.

In these same years, Ciabatti was working for the WorldSBK series organisers. I suppose their firsthand knowledge of my racing experience together with their experience of what riders appreciate, inspired them arrange with Michelin’s Piero Taramasso a set of ‘real’ MotoGP Michelin tyres on their GP22 for my test on what’s clearly the best bike on the MotoGP grid this year, the Ducati GP22.

This is not usual, actually it’s quite rare. Michelin’s MotoGP tyres are strictly allocated. In addition to this, the tyres must be used in the correct temperature window – and we’ve all seen what happens to GP riders when they let the temperatures drop outside these very narrow parameters.

In my experience of slick tyres, the general rule is the higher the level of grip attained by a tyre manufacturer, the narrower the temperature window is that those tyres should be used in. I understood the weight of what Ciabatti, Tardozzi and Taramasso had arranged for me – it was something very special. I would get to test the best racebike on the planet on the tyres that its suspension, geometry, electronics, carbon brakes and aerodynamics were all designed to be used with. This meant that my experience would be the real experience Ducati MotoGP riders have.

I sat in Pecco’s chair with Ducati test rider Michele Pirro and his awesome test team lead by crew chief Marco Palmerini. Ciabatti told me that Michele would lead me around some laps and then let me in front for some laps.

“Three behind and three in front?” I replied. If I had raced Misano the current direction I’d have suggested less laps with Michele leading, but I was not confident I could figure out the two corners after the fast turn at the end of the back straight, which don’t flow naturally to me, as they were designed to be used in the opposite direction as I had raced them.

All MotoGP machines sound beautiful, but the Ducati GP22 possesses my favourite sound of all of these elite machines. It literally makes the hair on my arms and neck stand up with excitement. Pecco Bagnaia’s Ducati GP22 was warmed up, it was time to ride…

Remembering my first experience of a MotoGP bike when I rode the KTM RC16, I avoided using the low rpm that I would normally use on a production motorcycle when taking off in order to be nice to the clutch. The timing of the valves, etc., on a MotoGP engine are set to be most efficient in the rpm ranges used when racing – they simply won’t run at low rpm, the engine judders and ‘bunny hops’ making a similar sound to bikes on the pitlane limiter. A slightly higher rpm is needed to avoid looking like a complete novice. I’d spent time studying MotoGP riders leaving their pit garages at races.

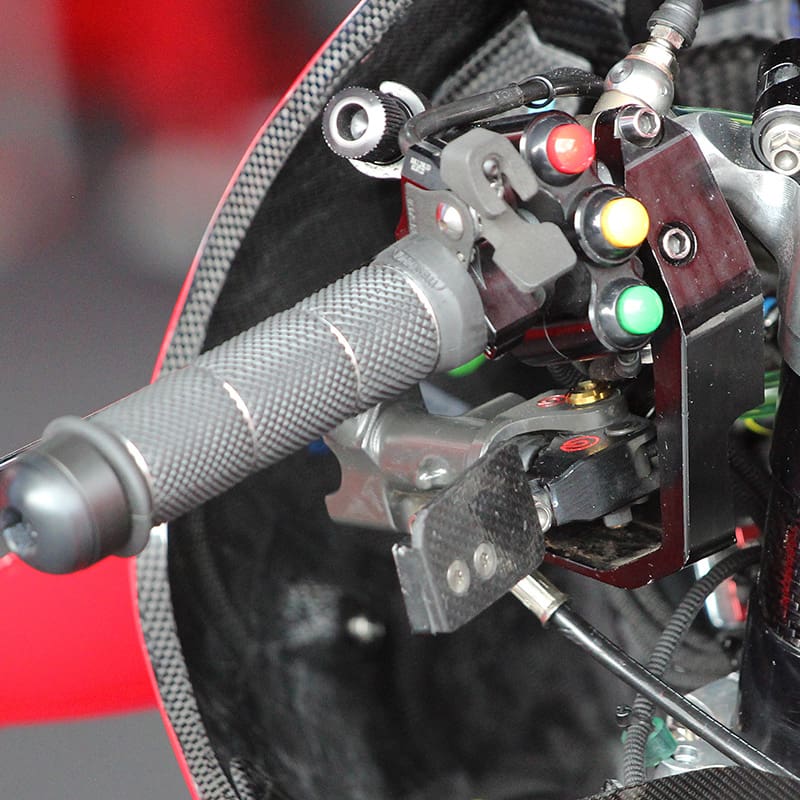

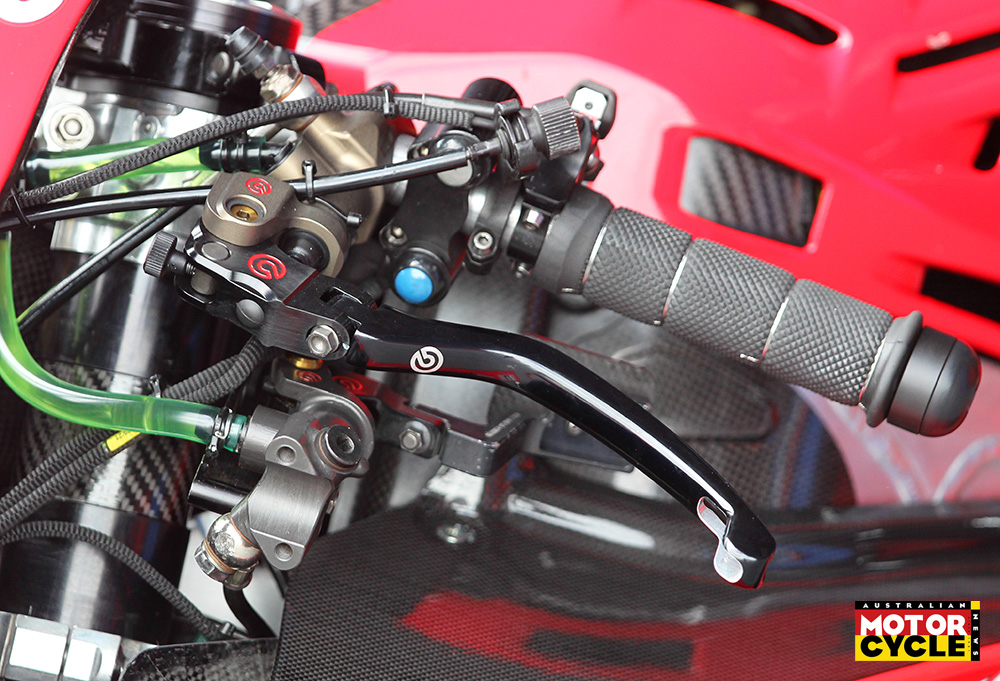

I nailed the take off and might have felt pleased with myself if I wasn’t so busy thinking that I had just experienced the most perfect clutch feel of my life! I did not expect to notice something like that. As I traveled down pitlane I lightly dragged and gently pumped the front brake lever as Michele was doing ahead of me, taking care not to do this with any lean angle while creating temperature in the brakes. This is no joke. Carbon brakes do not work at all when cold. The first pull of the lever gives no result which is very unnerving if you do not expect this, or have forgotten. Also, once they reach working temperature their braking power increases suddenly, so you must be ready for that also.

As we leave pitlane, I get my first taste of the throttle connection, acceleration and that wonderful seamless gearbox – a highlight of my previous MotoGP bike experiences – but at this point all my focus is on trying to understand the feel of the tyres through the response of the suspension, chassis and feel of the throttle, because crashing this wonderful piece of machinery is not an option. Far too much trust has been placed in me to let that happen.

The next thing I notice is how responsive the Ducati GP22 is to my inputs. Not twitchy at all, quite the opposite. Stable, but also responsive. Not something I’d previously felt simultaneously, because bike setups usually create one or the other. When I push on the inside ’bar to get the bike to lean over, it did it so willingly – at least at the low speed I was currently travelling. Once leaned over, it did not need input to stay there. I like this. I hate bike setups or tyre profiles that require input to stay on their side, because this takes energy and concentration when you need it free for other things, like feeling the edge of grip. I was far from that edge at this point I know, but it was nice to feel such a neutral-handling machine while I took small, hesitant steps toward the edge, without going over it.

The exit of Turn 6 onto the back straight was the first time I felt the throttle connection clearly, the power delivery with the throttle wide open through its full rpm range to understand the curve (something professional riders learn to notice and remember from the first lap on a machine), the rear tyre, the rear suspension, the gearbox, the front contact/ wheelie and stability under acceleration. All this feedback allowed my confidence to grow.

Ambient temperature was 35ºC and the track temperature even higher, so getting my tyres up to temperature was of little concern.

The position of literally everything on the motorcycle was comfortable for me, and my excitement grew as I accelerated towards Turn 8. I now literally felt young! I was cautious mid-turn, as that’s where I knew I could get caught out. But on the gas and brakes while relatively upright, I felt confident to push with low risk – so I did. The brakes did not surprise me, I raced with carbon brakes on the 500s in the 1990s. The difference I felt now was that these carbon brakes heated up faster and easier, making them a lot safer.

The next moment Michele was waving me past onto a completely clear track ahead, so I wrung everything out of the engine along the front straight and braked for Turn 1 where I had picked a marker on the previous lap. I must have been traveling a bit faster than previous, because although I was stopping well, I felt the rear wheel lift gently into the air. What happened next was completely unexpected. While off the ground, the rear wheel stayed perfectly in line, came back down gently as I reduced brake pressure slightly and once the rear tyre made contact with the track, it did so smoother than I have ever experienced. Somehow the rear wheel speed matched perfectly with the surface so I felt no change, no rear wheel slide or stepping out. I could then push on the right handlebar to enter the turn on the line I’d wanted with the same brake pressure – how the hell did the Ducati GP22 do that?!

I had not used the clutch to match the rear wheel speed while braking, it had done it by itself. I grew up riding Superbikes without slipper clutches. Then slipper clutches arrived in the mid 1990s and things improved a lot, but still I used the clutch to help match the wheel speeds and engine brake precisely with with the ever-changing rear grip. What I’m saying is, I am good at matching the rear wheel speed with one finger on the clutch, but this bike had just done it more perfectly than I had ever managed in my life!

What’s more, I don’t understand how the rear stayed so perfectly in line while off the ground. No motorcycle I have ever ridden had acted like this under those conditions – regardless of the manufacturer, the year or the price tag. Unless they had been set to ‘no engine brake’, which I don’t like, they had all lifted, come around or ‘backed in’ while going down through the gears when hard on the brakes.

Turn 3 at Misano forces the rider to accelerate at large lean angles. It is possible to change lines and reduce this, but in the end it’s unavoidable. This is where I got to feel how the electronics were working, as I wasn’t confident or fast enough on the rest of the exits, and even this one I was a bit hit and miss. After a whole career of racing without electronic rider aids, I absolutely hate to feel the bike slowing down when I’m opening the throttle.

Wheelie control on most stock bikes makes me angry, so I turn it off. If traction control is too intrusive I set to minimum, but traction control does help keep riders safe. The dream balance is when you don’t feel it, letting you believe that you are in control and lets the rider feel the rear tyre move, but in the background ready to save you if you get it wrong. This is how the GP22 felt the couple of times I got close to getting it right. Basically the Ducati GP22 kept going forward, letting me feel as though I was in control.

It was in Turn 8 that I got to really feel how the chassis turned. It’s an entry that did not expose my weak point, which is quickly getting to big lean angles. I had been staying on the brakes too long, reducing speed too much because I was afraid to put my faith in the front tyre. Even though it was the best front tyre I’d ever used, throwing the most expensive bike I’ve ever ridden on its side at very high speeds takes more than six laps to achieve. I braked hard in a straight line toward Turn 8, braked towards the corner and gradually reduced pressure and leaned in in a slow transition. I released the brake to enter the corner still carrying some speed and felt that the bike did want to turn. I had expected less turning for such a long-looking V4, but it was good in this area, too.

I headed down to the tricky right-hand corner that leads onto the back straight. Again being too careful (another word for being a chicken), I was slow mid-turn and the rpm dropped just out of the optimum range and that aforementioned stutter momentarily replaced the perfect engine feel. Two seconds later it had pulled out of that range and was ready to go, just in time for the exit. I stood the bike up a little more and opened the throttle, we were off like a shot, racing through the gears!

It was then I realised that more than fast, the engine felt smooth. So smooth was the delivery all the way through the rev range that it felt, well, not super fast. I know that is ridiculous because it is! I believe that because we humans perceive changes in acceleration more clearly than acceleration itself, the power delivery on the GP22 must be so linear that my brain thought we we not accelerating as fast as we were. Impressive.

At the end of the straight in sixth gear, approaching the fastest turn, I felt surprisingly confident which leads me to surmise the bike was so stable and accurate, it let me believe I could do it no problem. I used the knowledge of how to tackle fast turns that I’d built up over decades, and the bike responded.

Once through it I was lost, not knowing whether to gas or brake, I just rolled through the next two corners. I wasn’t much better into or through the tight right hander either, as it has a few bumps I was afraid would catch me out. The last two left handers I felt okay, but the bike felt amazing. I had a big smile on my face as I accelerated out of the last turn to complete the lap.

Five laps in, I was tired and afraid of making a mistake. The sixth lap I did while struggling to talk for the video I was making, before a very slow in-lap chattering and puffing but absolutely buzzing.

I knew the GP22 was going to be good, but I did not expect it to be that good. It is the first motorcycle I’ve ever ridden on track that I did not want to change a single thing on – it was better than me in every area. A true Masterpiece.

Once stopped in pitlane, I hugged Michele, thanked him and apologised for being lost on certain parts of the circuit. He replied that I’d done a 1m35s and that he would happily sign up now for a 1m35s at 53 years of age. I imagined he was just being kind to a very happy ex- rider, but now I hope he half meant it. All I could think at the time was, once I get my breath back I would love another run out on this GP22!

Tech specs

(Well, as much as Ducati will tell us anyway!)

Engine 90º V4, Desmodromic DOHC, four valves per cylinder

Capacity 1000cc

Power Over 250hp

Top speed Over 350km/h

Transmission Seamless six-speed

Fueling Indirect electronic injection, four throttle bodies with injectors above and

below the butterfly valves

Electronics Marelli ECU programmed with Dorna Unified Software

Chassis Aluminium alloy twin-spar

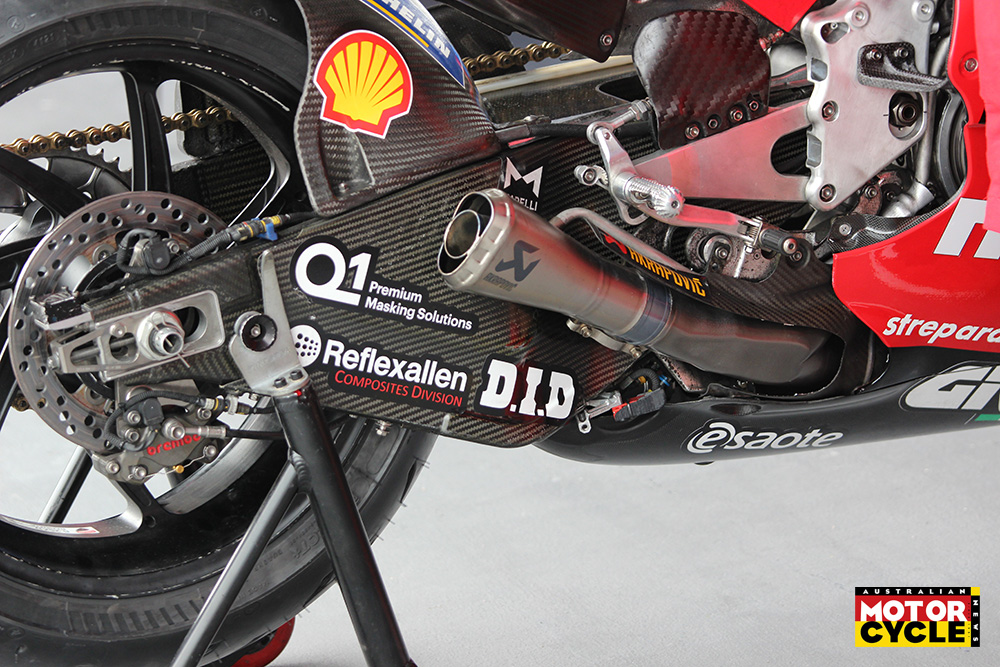

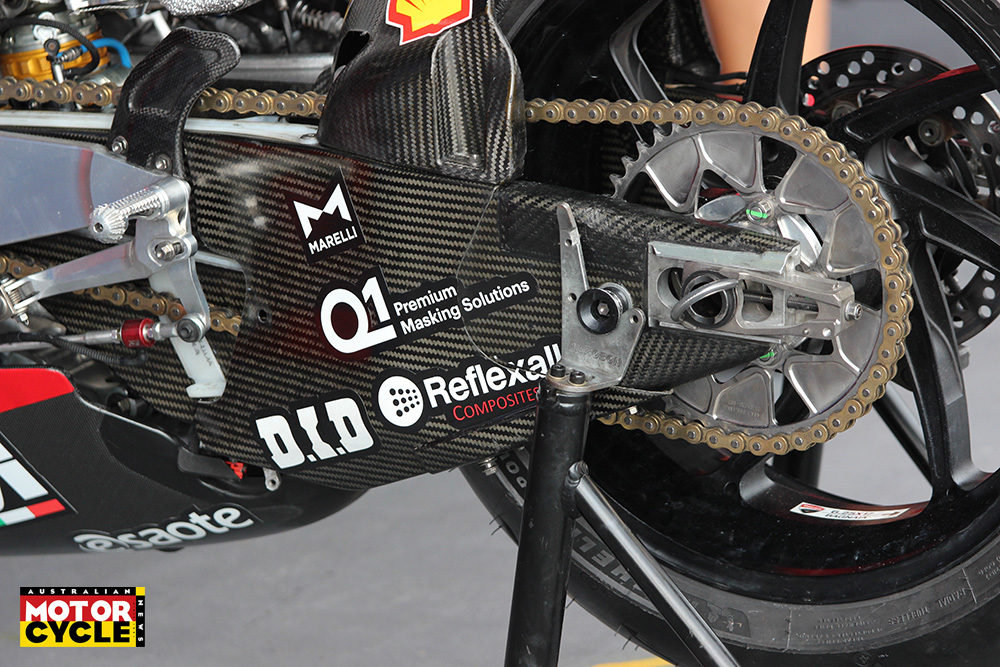

Suspension Fully adjustable Öhlins USD fork with carbon outer tubes, and fully adjustable Öhlins rear shock

Wheels Magnesium alloy by Marchesini

Tyres 17-inch Michelin MotoGP-spec

Brakes Twin 340mm carbon discs with four-piston Brembo calipers, and stainless-steel rear disc with twin-piston caliper

Weight 157kg (dry)