Right now Ducati is proving that if you stick to what you know, you earn trust and confidence from your customers.

The Italian factory is in the middle of record sales growth. Last year its worldwide sales increased 22 per cent. The trend has already continued this year with a 31 per cent increase in Australia alone in the first quarter. This remarkable growth should continue as nearly half its 2016 line-up are new models.

Ducati’s success is based on one basic engine configuration: the 90º or L-twin. It is available in a huge range of options from the detuned, air-cooled Scrambler to the full superbike model of the 1299 Panigale.

Ducati’s product planning isn’t that much different to those of the major British motorcycle manufacturers of the 1940s and 1950s, which dominated the Australian market. Their sales platform was based on various versions of the parallel twin.

As the 1960s progressed, Italian manufacturers joined a lemming-like rush to make their own parallel twins. This included Laverda, Benelli and Ducati.

However, Ducati had earlier form in this area, developing several parallel twins as pure racers, not street models.

Strangely, it had three stabs over three decades at making a go of the parallel twin, but none delivered the sales success Ducati was seeking.

Yet the parallel twin is an enduring design. First brought into major motorcycle production by Triumph in the 1930s, the concept survives today with latest efforts including Honda’s top-selling Africa Twin adventure bike.

Ducati’s various attempts at the parallel twin have seldom been documented in any detail. Certainly, Phil Aynsley is the only person to have photographed in detail all the surviving Ducati parallel twin models.

Each is an amazing story.

TWIN SPORTS

By the mid-1950s Ducati’s SOHC 125cc single was the bike to beat in Italy’s hugely popular long-distance road races.

An example of its dominance was when factory rider Giuliano Maoggi won the Moto Giro outright in 1956. Over a gruelling 1200km, he left the entire 175cc class in his wake.

But things were different on the world stage with both the 125cc and 250cc Grand Prix championships reeling from the dominance of NSU’s twin-cylinder racers of 1953-54.

The NSU twin was destined to have a huge influence on motorcycle racing design, especially for Honda. But unlike Honda, Ducati already had the concept in hand – designer-engineer Fabio Taglioni had first drawn plans for one back in 1950.

Ducati’s thinking in 1955 was if it was going to get serious about world-class racing it needed to look beyond its single-cylinder technology.

Its first twin appeared in public at the Milan Show in 1956 and the 175cc racer was entered in the 1957 Moto Giro. Overweight and with a peaky power delivery, it wasn’t competitive, and rider Leopoldo Tartarini was probably thankful to be sidelined by electrical issues.

Taglioni used the 175cc as the prototype for a 125cc GP racer and, later, a 250cc version. There is no record of the engine being developed for a road model. Its complicated design would have made this a financial risk.

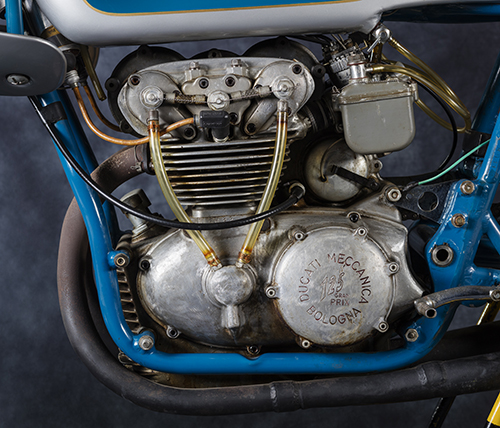

The 175 was a distinctive engine and quickly earned the nickname ‘Il Testone’ (Big Head), for its dominant DOHC housings.

It ran a 180º crank, creating a ‘rocking couple’ with much less inherent vibration than a conventional 360º throw. Two separate flywheel assemblies were clamped on a central shaft with a spur gear. This activated a series of cogs that eventually drove the camshafts. As well, a jackshaft transmitted drive to the clutch.

It was a complicated assembly that included a serrated-toothed Hirth coupling, a design first used in aircraft radial engines. This system gives a strong connection that is also self-centring but is very fiddly to assemble.

An Achilles heel of the whole design was the large idler gear. This was prone to cracking, which then destroyed the engine’s top-end containing the double overhead cams.

An 11:1 compression and peak power produced at 11,000rpm meant things happened pretty quickly inside those cases. It was making 30 per cent more power than Ducati’s 175cc SOHC single but it weighed a lot more and had a tiny powerband.

After the abortive Moto Giro, the 175 was shelved while Taglioni developed the 125cc GP version, this time using desmodromic valve operation.

Ducati’s US importer, Berliner, took the forgotten valve-spring prototype Stateside and raced it in the popular 175cc road-racing class. Berliner would go on to play a major role in future Ducati twins.

When the 175cc class died out the little Ducati returned to Italy in the early 1960s where former factory rider Francesco Villa turned it into a 250. He bored and stroked it from 49mm/46.6mm to 55.2mm/52mm and cast new heads and barrels. He also built a new, lightweight frame based on the 125cc GP racer with upgraded forks and brakes. The surviving version pictured was captured by Australian photographer, Phil Aynsley.

Revving now to 12,000rpm and producing 40 per cent more power than the 175cc version, it was raced successfully in Italy until Villa moved on to work for Mondial.

The 125GP project also stuttered along, with only three built. It was first raced in the 1958 Italian GP at Monza by Francesco Villa. He finished third among four Ducati singles. This wasn’t a good omen, and the result wasn’t bettered. In 1959 Luigi Taveri finished in the same position after a year of haphazard development. The twin that Aynsley photographed is the Monza GP bike.

To put this into perspective, Taveri finished fourth in the championship riding both the Ducati twin and an MZ two-stroke while a young Mike Hailwood finished third on a Ducati single, the bike that the factory thought had passed its development peak!

The 125 made the same power as the 175 prototype but at a heady 13,800rpm. This is where the desmo system came into its own, protecting the engine from over-revving, especially on downward gear changes. While it was more powerful than its rivals it was heavier and, again, the powerband was small and hard to access.

In a rare moment of misjudgement, Hailwood’s wealthy father and sponsor Stan, obtained two 125GP twins from Ducati for the 1960 season but they were a disaster.

Meanwhile, Villa’s original 125 was raced and developed in Spain by Ducati partner Mototrans. It received a 15 per cent power boost with the rev ceiling lifted to 15,000rpm, although it boasted a wider powerband. It was raced well into the 1966 season in both Spanish and Italian national events.

When Stan Hailwood ordered Mike’s Ducati twins he also commissioned 250cc and 350cc versions. These bigger machines looked similar to the 125 but few parts were interchangeable.

Again, they were as powerful as their opposition, but heavier and handled so badly that several aftermarket frames were built for them.

The 250 that Phil photographed was sold by Stan Hailwood to John Surtees in 1961. Eventually, Surtees fitted the Ken Sprayson frame and leading-link front forks featured in these photographs.

And so ends the first chapter of Ducati’s dalliance with parallel twins.

Ironically, during this period Ducati was carving out a well-earned reputation for tough, competitive, privateer-affordable DOHC single-cylinders that filled grids around the world.

Paralysed twin

Surely Ducati had realised by the 1960s that developing twins was a dead end.

Well, no. It jumped back into the shark’s pool, this time with its mind on the booming American road market.

By 1964 Triumph and BSA twins were roaring out of showrooms across the continent. Oh, to get a slice of this action, thought Ducati’s muddled management.

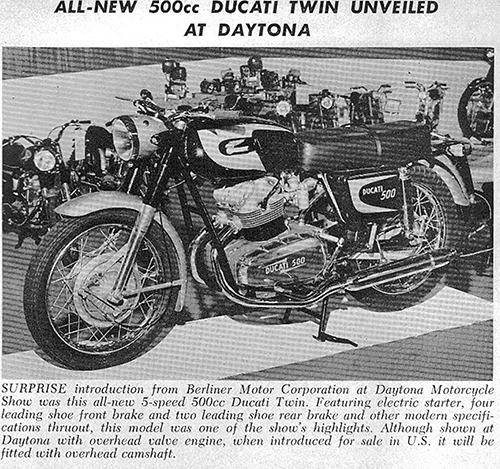

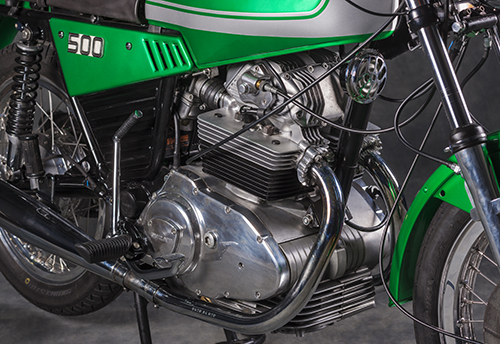

Its small-capacity single-cylinder models had carved out an important niche in the world’s biggest motorcycle marketplace. Now it was time to take on the British at their own game. Urged on by their US distributor Berliner Motor Corporation and by news that Benelli and Laverda were developing similar twins, Ducati came up with a 500cc parallel-twin, displayed as a concept at Daytona in early 1965.

It featured British-like pushrod OHV operation and a 360º crank but had something the limeys didn’t – an electric starter. Unfortunately, whereas existing British twins were svelte, the Ducati was big, clumsy and sluggish, weighing 190kg dry. Despite a lukewarm response from observers, Berliner, which also distributed Norton and Matchless, thought the design had legs. Remember too that these were the pre-Norton Commando days, so no obvious all-new British model was on the horizon.

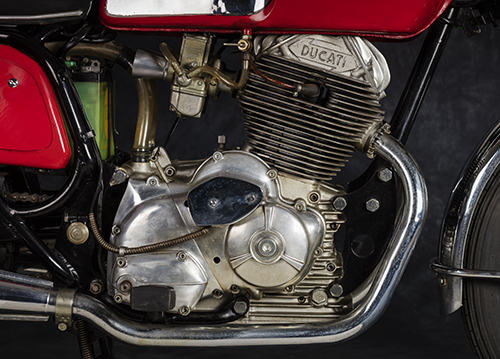

The factory persisted and in 1968 it revealed a completely revised version to its American dealers. This was lighter (178kg), more powerful, sported a five-speed gearbox and borrowed a lot of styling cues from the popular road singles.

Sadly, the time had passed as Honda’s CB450 twin was already on sale and Norton’s Commando had just hit the market.

The US dealers had also heard that Ducati was developing a big V-twin. That made more sense to horsepower-hungry Americans.

(Interestingly, Honda never achieved the sales it sought with the CB450 and it was restyled in 1968.)

The extent of Ducati’s interest with parallel twins between 1964 and 1968 was bordering on obsession. As well as the 500cc version it also experimented with two disparate 700cc concepts, a DOHC sports roadster and a pushrod police cruiser. But these ideas came to nothing, and ultimately prevented the factory from focusing on a redesign of the 500.

So the crisply styled and compact 1968 500cc prototype photographed by Phil Aynsley at the Bologna factory remained just a concept, tucked away and forgotten. It has rarely been seen in public and hadn’t been photographed in detail since 1968.

Another episode had closed in the parallel twin saga that was fast becoming a soap opera.

Twin Trials

So we arrive in the mid-1970s when Ducati, after several changes of management, were cooking up another grand plan. Taglioni’s big V-twins were selling well but the corporate bigwigs were convinced the single-cylinder models were nearing the end of the road and the 750cc V-twins were too elitist.

Spurred on by the 1973 oil crisis, a decision was made to develop a whole new range of small, affordable twins. Unfortunately, Taglioni’s suggestion of a V-twin layout was ignored and the parallel-twin plan was reactivated. More years of pain lay ahead.

If Taglioni’s idea had been followed, Ducati’s Pantah would have hit the road five years earlier. The factory had been developing a 500cc V-twin GP racer so all that experience and engineering was waiting to be exploited. But, no. It was to be a clean-sheet design, with all the inherent risks. Taglioni turned his back on the project and continued developing what would eventually emerge as the 500cc V-twin Pantah.

Following a well-trodden path, other Ducati engineers started with a vibrating 360º parallel twin, but soon saw the light and reverted to the 180º ‘rocking couple’ idea first seen in the original 1950s 125cc GP racer.

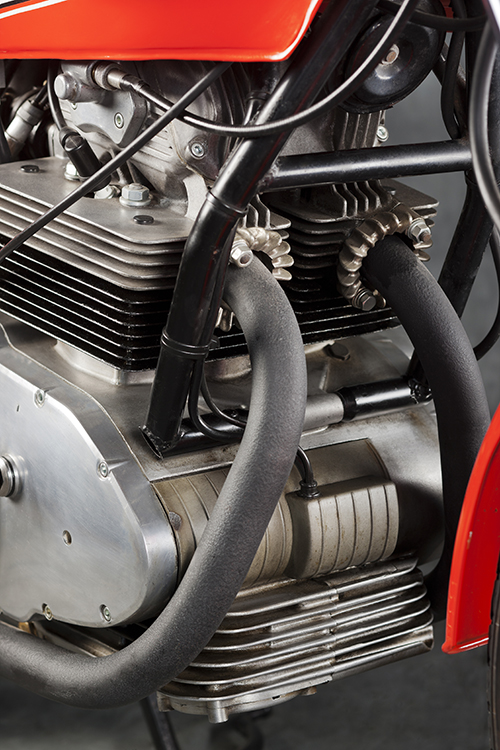

Their results were revealed at the Milan Show in late 1975. Three models were offered: 350cc and 500cc versions with overhead valves and a chain-driven cam; and a sporting 500cc option with desmodromic valve actuation.

In a classic case of a manufacturer trying to second-guess the market, the least valued option proved to attract the most interest. The Sport Desmo had only been added as a sweetener but it overwhelmed potential sales of the valve-spring GTL models.

In typical Ducati fashion, the Sport Desmo wasn’t available in big numbers until 1977, by which time production had been outsourced to the Italjet factory. Ducati supplied the 350cc and 500cc desmo engines; Leo Tartarini of Italjet the styling and manufacture.

While the performance and build quality were underwhelming, the styling helped bring Ducati into a new era of sales and credibility when it was applied to the new V-twin 900 Darmah model a year later.

The valve-spring GTL models had featured the unloved looks of the 860GT, which had been dreamt up by a car designer! Tartarini’s styling was applied to the valve-spring engine and it was relaunched as the GTV in 1977.

The Sport Desmo models looked fresh and lithe, despite their enormous engine crankcases. Originally designed to contain counter-balancers for a 360º crank, they now incorporated a remote reservoir for the supposedly ‘wet sump’ engine. This involved complicated internal plumbing, the need for frequent oil changes and keeping a critical eye on fluid levels. This was beyond many owners, with inevitable results.

So although the little twins had rock-steady handling, they were blighted by reliability issues and a short engine life of as little as 20,000km.

Despite this, Australian distributor Norm Fraser Imports sold a steady number of the parallel twins. Factory figures reveal that Fraser imported 491 Desmo 450 singles over that model’s lifespan. When the twins came along it imported 208 valve-spring engined 500cc GTLs between 1975 and 1978, 36 GTVs in 1977 and 224 of the Sport Desmo over the lifespan of that model.

By the late 1970s, mainstream motorcycling was heading into the big-bore, multi-cylinder superbike phase led by the Japanese. Even their small-capacity models were now powered by multi-cylinder engines.

An example of how Frasers fitted into this ‘big-bore’ market is that it imported a whopping 427 Darmah V-twins in 1978 and a total of 1641 (including the SSD first released in 1979 and discontinued in 1982) over that model’s sales run that ended in 1984.

When Taglioni’s sports-focused Pantah V-twin arrived it elbowed the parallel twin out of a very small market niche and the concept was finally put to rest.

A total of 1418 various sized Pantahs were imported over that model’s lifespan compared with a total of 485 parallel twins of 350cc and 500cc.

Fast-forward a few decades and Ducati finally got the small-capacity twin model right with the Scrambler, which is quickly proving to be another sales winner for Ducati. Ironically, it’s a leaf out of Taglioni’s original 1970s ideas book: a scaled-down and detuned version of Ducati’s big air-cooled V-twin.

STORY HAMISH COOPER PHOTOGRAPHY PHIL AYNSLEY