The day you buy yourself a motorcycle is a special event that is to be relished, and if you happen to be buying a new Ducati Superbike you are paying premium money and can reasonably expect to receive a premium experience. So have you ever wondered what happens when you buy something even more expensive and exclusive from Ducati?

I’m talking about the Ducati Panigale 1299 Superleggera, a motorcycle that only exists because it can. I won’t go into the technical details as the hyperbole surrounding this machine means you’ve already seen the specs or you can easily find them (Vol 67 No 04). Only 500 have been made, and even that number can’t be justified on purely rational grounds.

Using the tried-and-true pretext that you only get to live once and you can’t take anything with you when you go, I found myself talking to my local Ducati salesman at the end of 2016 about a bike that didn’t appear to exist. Yep, strange as it may seem, there are no 1299SL brochures, it’s not listed on the company’s price list, does not appear on the Ducati website, and does not occupy public space in dealer showrooms. The Superleggera has its own website and was available on request only. It was almost clandestine.

Following a somewhat stilted discussion with the dealer, I eventually established that the 1299SL would eventually exist and that I could request a bike by placing a deposit, but – and this was emphasised – there was no guarantee that Ducati in Italy would allocate a motorcycle to me because their best customers (meaning 1199 Superleggera owners – which isn’t me) would get first preference and deliveries would be some time in 2017.

A few days later I put my name on the waiting list by handing over a cheque that would ordinarily be enough to buy a motorcycle outright (and a nice one at that) and then the waiting started.

Finally, several months later, I was down at the pub when my phone rang and a pleasant-sounding lady explained that she was calling from Italy and I’d been allocated one of the 500 machines to be built.

At the end of the call, I experienced a number of contrasting feelings: elation – I’m one of the lucky few; disappointment – I don’t need this bike, all I really wanted was to tell my friends that I tried to buy ‘the big one’; and concern – how, when and where do I tell the wife what I’ve just agreed to buy.

This last issue really was crucial. I’m happy to say my wife is a keen motorcyclist who rides an MV Agusta F4, but she’s a one-bike-at-a-time person whereas I tend to buy a motorcycle every few years but rarely get around to selling them, so over the past 30 years or so I’ve accumulated a few and therefore I’m regularly reminded that the garage is rather full already.

A few weeks later I received another call from Italy. A man asked, would I like to come to Mugello for a ride day? Bikes and food will be supplied, just bring leathers and safety gear…

What a question! Do I still have a pulse?

After a bit of wrangling, I managed to align an upcoming business trip with the trackday so at least I had a plausible excuse for the trip to Mugello. Then it dawned on me that, while I normally ride daily, I’ve spent the last four years working abroad, where I had only limited time in the saddle. I was out of practice. And since getting back to Australia, pure laziness meant I’d only just pulled my favourite daily ride out of hibernation – a Triumph Daytona 955i.

Some might consider the Triumph sporty, but let’s be honest, it’s no superbike. So in summary I had just signed up for my first trackday in five years at a place where I’d never ridden before and I would be riding my first superbike in about four years propelled by no less than 158.1kW. I needed preparation. I dusted off the old PlayStation and bought a second-hand copy of a driving game that included Mugello so I could spend a couple of evenings learning the track. Then it was off to Italy…

On the first day I travelled to Bologna and attended a factory tour. It was interesting stuff, but the race department was off limits, in spite of my direct requests, pleas and other attempts at coercion – as was the prototype laboratory, so no preview of the new V4 Superbike before EICMA.

The tour guide explained that the factory works as a ‘just in time’ assembly plant and that 80 per cent of the bikes are built to order.

The parts are provided by suppliers and only the crankshafts are finished on site, in the machine shop. Each Ducati engine (for all models) is individually assembled by a pair of technicians in about two hours, and is then tested by being spun up in a test machine but is not actually started.

The motorcycles are built on one of four production lines, where each machine is completely assembled by another pair of technicians. This takes about three hours per bike. After completion, each bike is fuelled and started and three separate running tests for functionality and emissions compliance are undertaken. When I was there we saw several completed Panigale 1299R Final Editions at the end of the line.

At this stage there is no bodywork, so the motorcycles are taken to another location where the panels are fitted. Then they’re crated for shipping to the final destination.

Following the factory tour we went upstairs to the factory museum, where a small but significant collection of bikes is on display, along with exhibits showing Ducati’s origins in typewriters and electrical components. The motorcycle collection is predominantly either very early stuff (such as motorised bicycles) or racers. There are very few roadbikes, but what a collection. This is a company that truly believes the mantra that racing improves the breed.

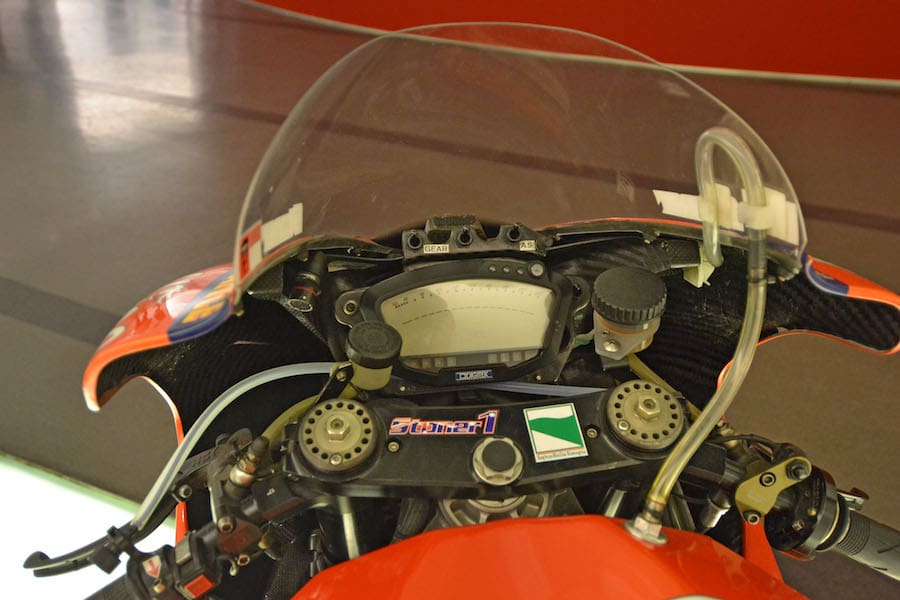

Standout displays included a streamliner, Paul Smart’s Imola winner, Mike Hailwood’s NCR from the Isle of Man and lots of championship-winning machines. We Australians are well represented with Troy Corser’s 916 Superbike, Troy Bayliss’s 996 and 1098, and of course Casey Stoner’s MotoGP title-winning 800cc Desmosedici.

The line-up of superbikes covering about 15 years of development shows the evolution of the class. The early 851-based machines were clearly strongly related to the roadbikes, whereas by the time you reach Bayliss’s 996 it looks far more like a prototype machine.

The next day, a group of people from all over the world (including Hong Kong, Macau, Germany, UK, Brazil, Mexico, South Africa and Canada) descended on Mugello. On arrival there was a quick medical check and then I finally got to see a 1299SL for the first time. If ever there was an embodiment of the expression “a young person’s motorcycle that only an old person can afford”, this is it.

I had been lured to Mugello on the premise that I would get to ride the Panigale 1299S, Panigale 1299SL and the Panigale R Superbike, which I had naively assumed would be the roadgoing homologation model. However, at the pre-ride briefing the day got even better – the Ducati Factory WSBK team was present, complete with Chaz Davies and Marco Melandri, and we would be let loose on a proper Superbike racer! Suddenly I was paying even more attention than usual as our hosts explained the differences with the racebike. Ultimately the biggest takeaway was that the clutch is different and very heavy, so we were to use it for starting and stopping only, using the speedshifter the rest of the time.

The briefing also included the following sage advice: Ducati is perfectly satisfied with Chaz Davies and Marco Melandri riding on the Superbike team and with Andrea Dovizioso and Jorge Lorenzo on the GP team, so this day was not a job interview and any attempts to impress the Ducati team would be useless.

A second piece of excellent news was also delivered – our antics were to be photographed and filmed. If you were slow the video speed could be altered, but our stature and riding style couldn’t, so we were advised to concentrate on looking good.

And that wasn’t all. Ducati is owned by Audi, which also owns Lamborghini, so a brace of Audi R8s and Lamborghini Huracans had also been put at our disposal to test. This trip just kept getting better.

Finally, on a hot 40º day in Italy, I pulled on my leathers (thankfully they still fit) and went to grab my ride. The pitlane contained a row of gleaming Ducatis, including several 1299SLs, each numbered XXX/500 on the top triple clamp.

First up was the 1299S, and we were grouped in pairs behind instructors who would show us the correct lines. As I eased out the clutch and headed down pitlane after a five-year track hiatus I found myself being reintroduced to muscles I’d forgotten I had. For the first time in my life I thought, “Maybe I’m too old for this shit.” Then, as I merged onto the track, stretched and entered Turn 1, the years melted away and a smile from ear to ear appeared on my face.

I wobbled around the track for a lap, cruising along the straight, and since I don’t yet have a bike with a quickshifter it wasn’t until the second lap that I figured it was time for this old dog to learn something new. I tried shifting without the clutch and wow, it worked excellently, especially downshifting. Then, just as I was getting used to the shifter and the track, my time on the 1299S was over.

Mugello is an interesting circuit, and I can see why people who have raced there comment on the fans and the noise because the pits are in a valley and the fans up on the hills.

Most of the corners are approached blind so you need to remember where the track goes and have faith. Fortunately the corners are quite easy and don’t try to catch you out by changing radius and camber midway. However, the track does rise and fall constantly. To ride this circuit you need to have a good memory and my time on the PlayStation really did help me learn which way the track went.

Next up was the Superleggera. While it didn’t feel radically different to the 1299S, the track exhaust (from the kit) was fitted, so the 1299SL was louder and spat through the exhaust as you approached corners.

This bike inspired confidence, encouraging me to get on the throttle earlier in the corners, and at last my knee started to make contact with the ground. I even got to experience the traction control allowing me to drift the back end in a corner, another revelation. My previous experience with traction control was on the 1098R, a system that wanted to keep the wheels in line and therefore tended to disrupt progress. As a result I was constantly toning it down. But this new system is much smoother and unobtrusive; it lets you slip and never feels like it’s restricting progress. Full marks Ducati – even a mug like me can drift a superbike.

Some of my fellow test pilots commented on the brilliance of the Superlegerra’s brakes. They are identical to those on the 1299S but this bike’s lighter weight (both gyroscopic and absolute) means the 1299SL installation works even better. Personally I’ll need to try this feature at home, since I wasn’t stressing the brakes on any of the bikes this day.

Finally I got to try the Superbike. Initially it felt very normal. You push a button and it starts, settling into a gruff (well, loud) but fast and smooth idle, and then things suddenly change. You grab a very heavy clutch and engage first. The clutch drags badly, needing the brakes to hold it still, and not bogging the engine while taking off is a challenge. However, once underway it feels like the roadbike again – quite normal. This was the only slick-shod bike I rode on the day and even these tyres didn’t feel all that different to the rubber fitted to the roadbikes, which shows just how good the Pirelli road tyres are. Or maybe I just didn’t work them hard enough to get them working properly!

The racebike feels as light as the Superleggera and a bit more nimble. My knowledge of the track was still growing, along with my confidence, and by now I was rolling on the throttle quite aggressively just before the apex and I never noticed any movement in the racer, though I’m sure the factory riders would tell a different story.

The race exhaust provided lots of aural entertainment with a cacophony of pops and bangs every time I closed the throttle. The engine may be 100cc shy of the roadbike, but you’d never know, and it was very tractable with a wide effective powerband allowing me to engage and hold higher gears while I concentrated on my lines.

The gearbox was a revelation. The speedshifter has no issues with changing up or down at any time, and by the end of my session I was beginning to re-evaluate my strategy of holding gears on the short straights instead of making use of the gearbox.

Sadly, my track time was over all too soon. Back in the pits, one hot and sweaty Aussie got off the bike and started babbling enthusiastically and incoherently with the other guests. While the words weren’t always in the same language, the smiles on our faces said it all – we were having a great time.

Over lunch in the hospitality tent I got to meet Chaz Davies. He was a real pleasure to talk to and assured me that the racer I rode is nearly identical to his factory Superbike. After lunch I also met Marco Melandri and again found him to be very personable.

At the end of the day I have to thank Ducati for inviting me to such an event. I had a great experience. All that was left to do was go back to work – and figure out how to tell my wife why Ducati had been so nice to invite me to Italy for

a ride day.

WORDS ANDREW ALLAN

PHOTOS DUCATI ITALY

As published in AMCN Yearbook (Vol 67 No 12)