From 500GP video games in the 90s to Sturgis posters, illustrator Russell Murchie has done a lot. But these days, if it’s not drawn by hand, he’s not interested…

Russell Murchie loves two things, art and motorcycles. Neither of which he can trace back to his family or his upbringing. “I don’t know, I was 20, I just decided to buy a cheap bike and it sort of stuck,” he tells me as I walk around his studio admiring the walls which are covered in artwork, both his own and others’. It’s a late adoption that wasn’t exactly mimicked in his artistic journey, which kicked off in an era when digital graphics were in their infancy. Born in 1975, Russell was at the dawn of a new technology that would reshape visual storytelling in his lifetime.

“I started digital stuff really early on,” he recalls. While studying photography at Melbourne’s RMIT, he was introduced to computer graphics through a friend’s sister – a chance encounter that would eventually shape his career.

Motorsport video games

It was in the late 1990s when Russell stepped into a burgeoning industry; equal parts Wild West and cutting-edge innovation. Melbourne House – a pioneering Australian video game company that would later morph into Infograms and eventually Atari – was the proving ground for the self-belief evident in his demeanour.

“Back then, no one needed any experience,” he explains. “You could just go into 3D graphics without knowing anything.”

This was a time of transformation in the gaming industry. Small teams of 20 would spend two years crafting intricate projects, a far cry from the massive 500-person teams and $20 million budgets that would eventually dominate the landscape. For Russell, it was a golden age of creativity, where imagination could flow and technical constraints were more fluid.

In those days, Russell’s work wasn’t just about creating fantastical worlds in gaming spheres – his creativity was far more authentic. The company specialised in motorsport games, securing licences for world-class events like Formula 1, 500cc GPs and the 24 Hours of Le Mans.

“We worked with Kenny Roberts Jr.,” he adds. “Every time he was down testing at Phillip Island, we all had invites to go down there because we had the licence for the GP stuff.

“It was simulations – there was a fair bit of work involved with it. So we worked with him, the team and their engineers and stuff to make things as accurate as possible, which was great.”

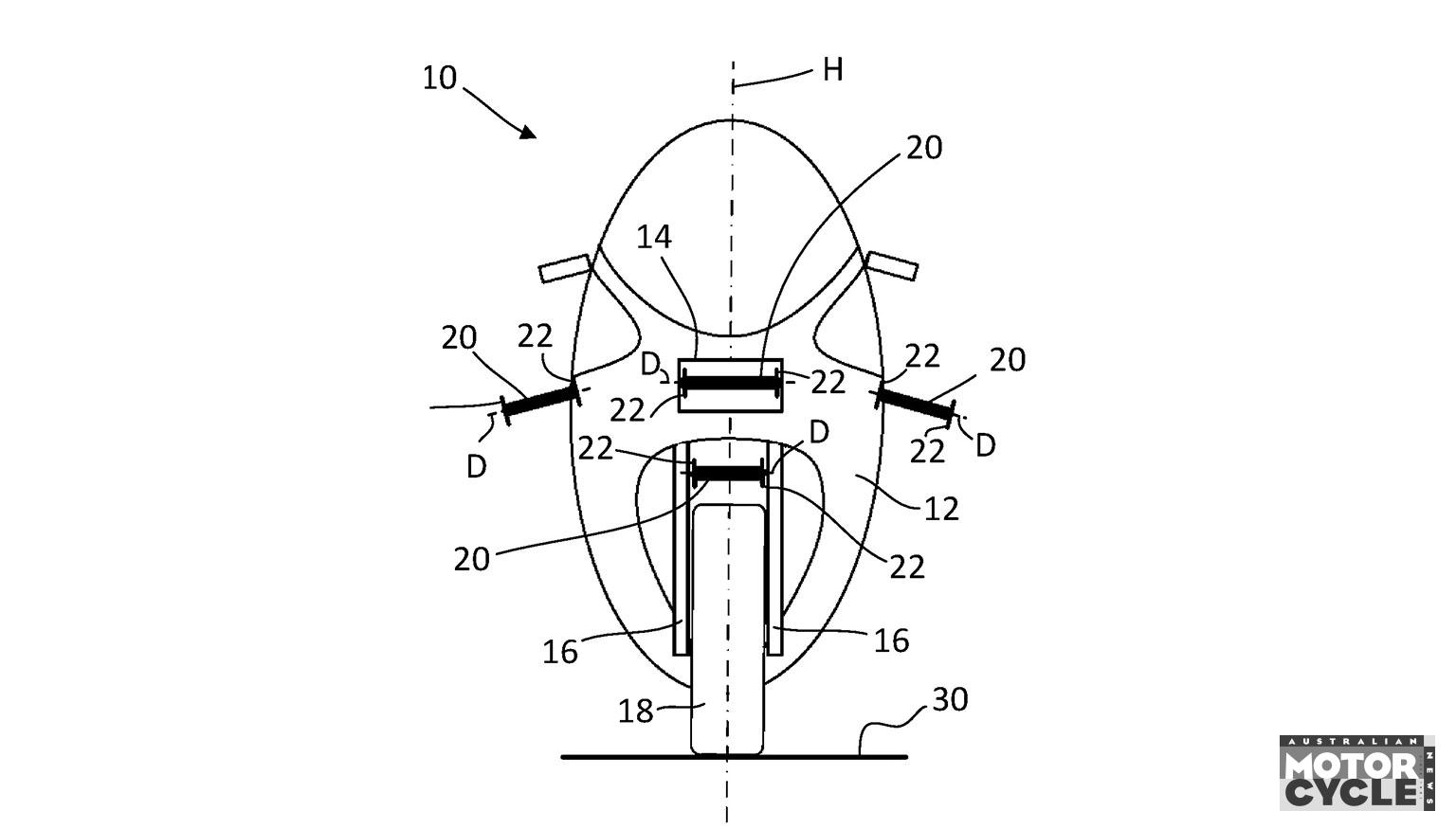

But the industry that had embraced Russell’s obvious talent began to change. As consumer expectations evolved, budgets began to grow exponentially and it meant less room for risk and a higher focus on technical perfection. For Russell, the final straw came when he was handed factory blueprints for a Maserati and was told he had six months to recreate it with millimetre precision.

“And I was like, no, I’m an artist,” he said. “I don’t want to just recreate technical stuff.”

A hard reset

Leaving the games industry led him to his father’s corporate graphic-design business – a job he describes as “the worst he ever had”. But life had other challenges in store. Within a few months, Russell experienced a perfect storm of personal upheaval – a divorce, his father’s death and being laid off from the company.

“And so I had to start again,” says Russell. “I’d just turned 40.”

In what would become a pivotal moment, Russell started posting “little doodles” on Instagram. And now, just 10 short years later, he’s working on his fifth commission to produce the official poster of the annual Sturgis Rally in South Dakota.

Those Instagram posts, like the majority of posts people upload to social media, were mere musings but they caught the attention of the organisers of the Australian bike show Throttle Roll, who reached out.

“They were like, ‘Oh man, we need an artist’. So I just did a little bit of ad-hoc design for them,” he recalls. “And that’s where I sort of started.”

Of course you don’t go from penning a few ideas for a little-known Aussie bike show to getting commissioned to produce the annual poster for Sturgis five times and counting without some persistence, hard work and a decent glug of luck.

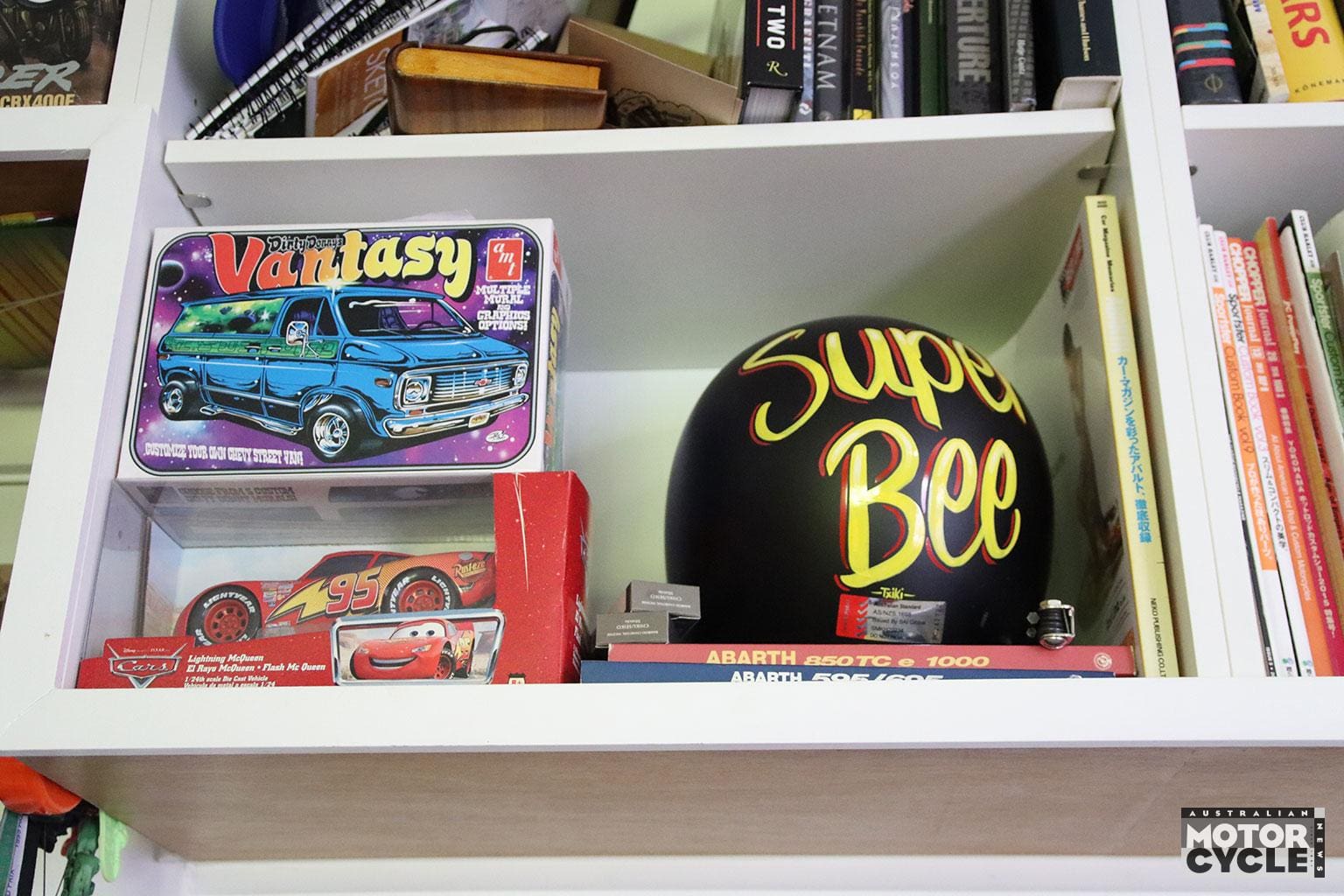

“I was in Tokyo one time and I came across a pinstripe exhibition just randomly in a little store,” Russell explains. “And I was talking to the guy who runs it, called Nash – this Japanese guy who knows all about custom culture.

“And he was like, ‘Man, we’re going to America, come to America with us!’ And then through that it sort of snowballed. But it’s been a process and meeting a lot of people along the way and just doing it, just doing everything.”

And it’s the meeting-people bit that Russell credits to his growing global recognition.

“I’ve put myself in a position to meet a lot of people. And that’s… trying to explain that to a lot of the younger guys is the hardest bit,” he says. “You’ve got to get on a plane, go and drink beer and shake hands and hang out with these people. And Japan is that one country where to do that, you really need to build those relationships over the years.” He stops and points to one of the scores of artworks dotted around his small backyard studio.

“That was for a Japanese company, I wanted a take on the Iron Maiden (band album) cover but with choppers,” he says before continuing the story. “I didn’t tell anyone I was Australian for about five years – people assumed I was from California. It’s just easier, especially for a lot of American companies… they want to mainly deal with guys who are local and get it.

“And there’s also the whole… I call it the Keith Urban Principle; you know, Keith Urban was active in Australia for a long, long time and no one gave a damn about him. It wasn’t until he went to America, then everyone’s like ‘Oh my god!’”

Canvassing inspiration

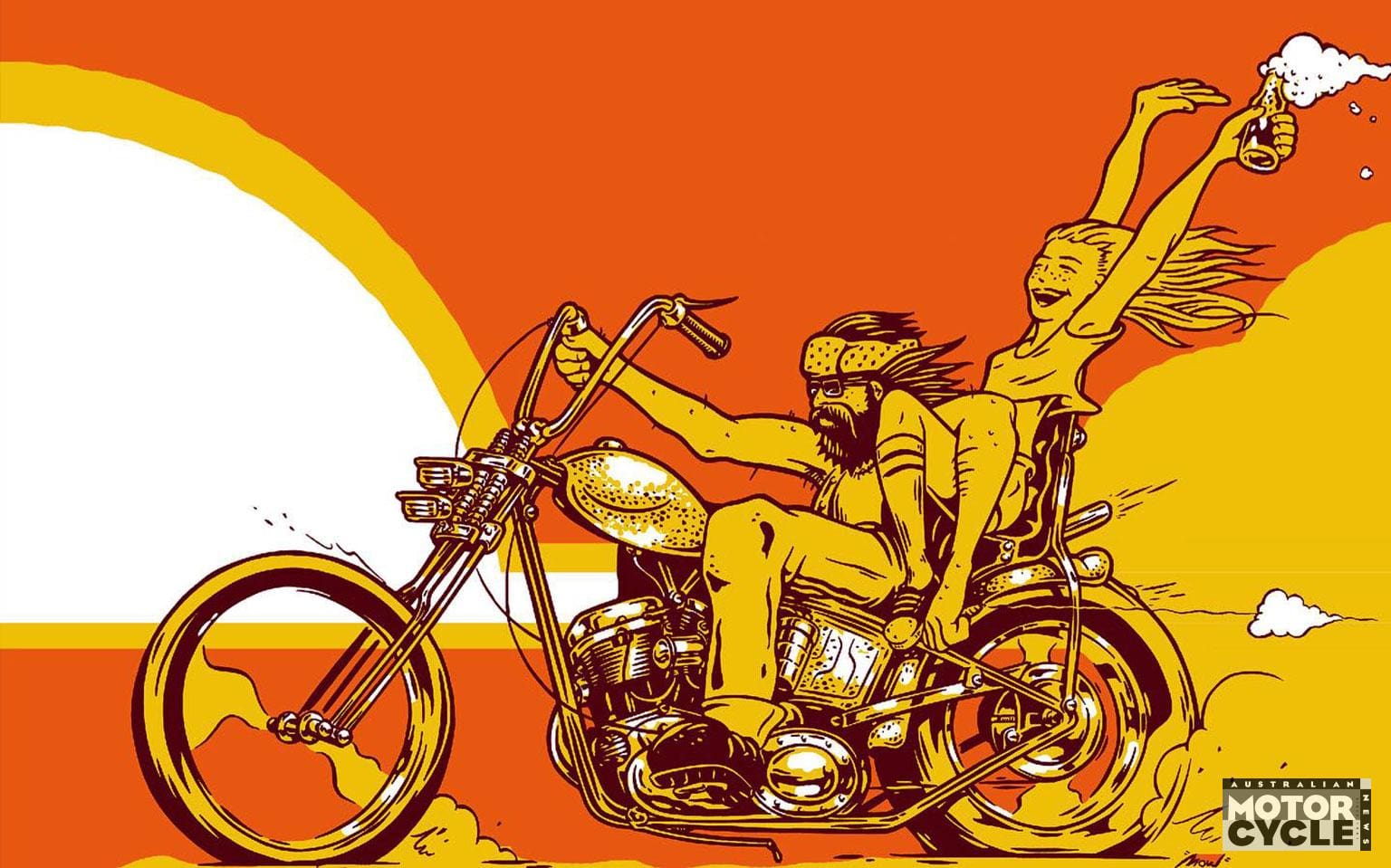

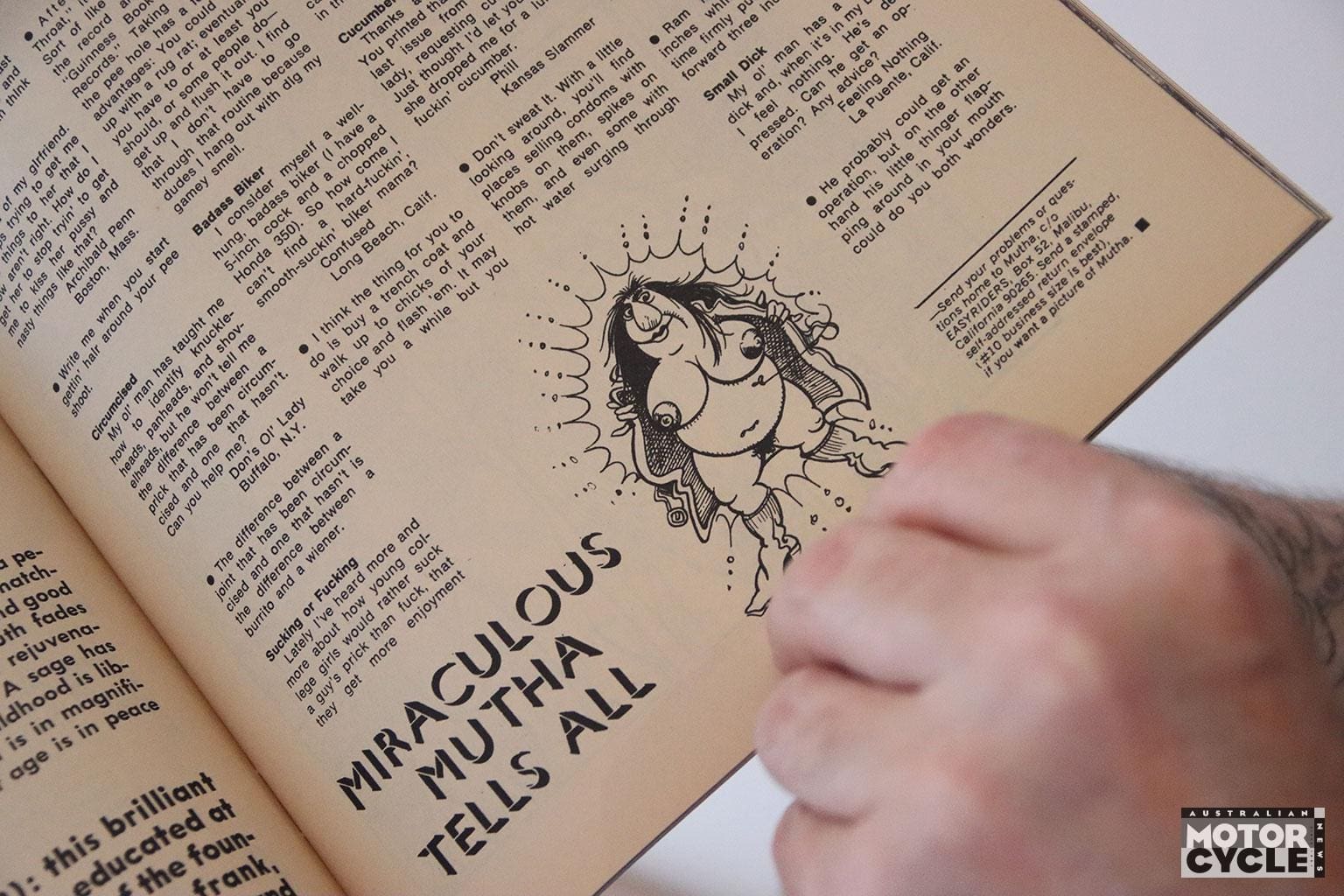

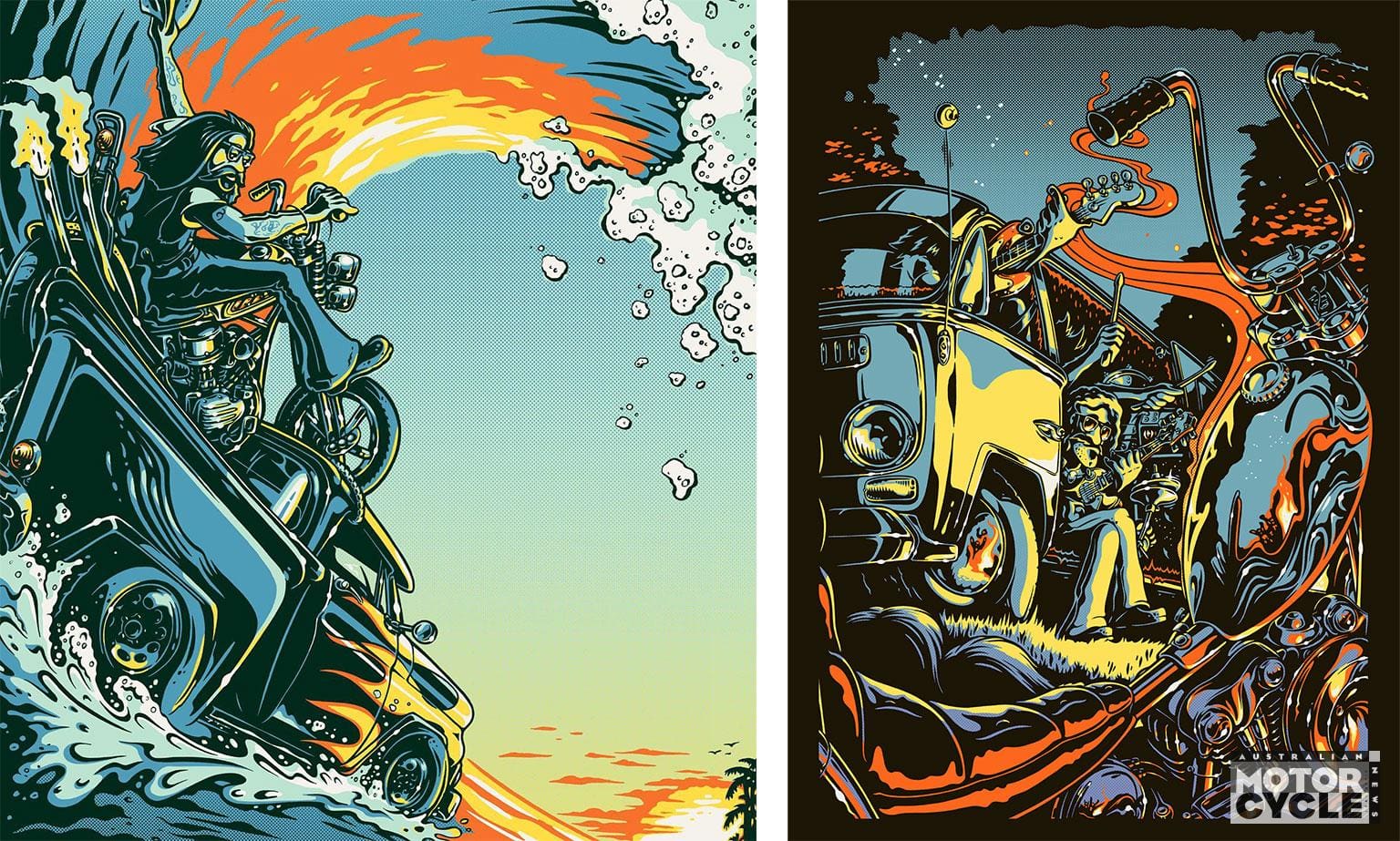

Murchie’s artwork is recognisable for its mix of influences; there’s Japanese woodcut, vintage tattoo flash, old-school Easy Rider magazines and a focus on people rather than machines.

“While my work features bikes, it’s not generally actually about bikes, it’s about people most of the time,” he offers, pointing to various examples around the room. “I’m interested in the people who are around bikes, because they’re a pretty eclectic bunch usually.

“That’s probably my biggest differentiating feature. Generally, people in my stuff are having a good time. A lot of bike guys are all about the skulls and flames and, you know, bad dudes and shit – that’s not part of my personality.”

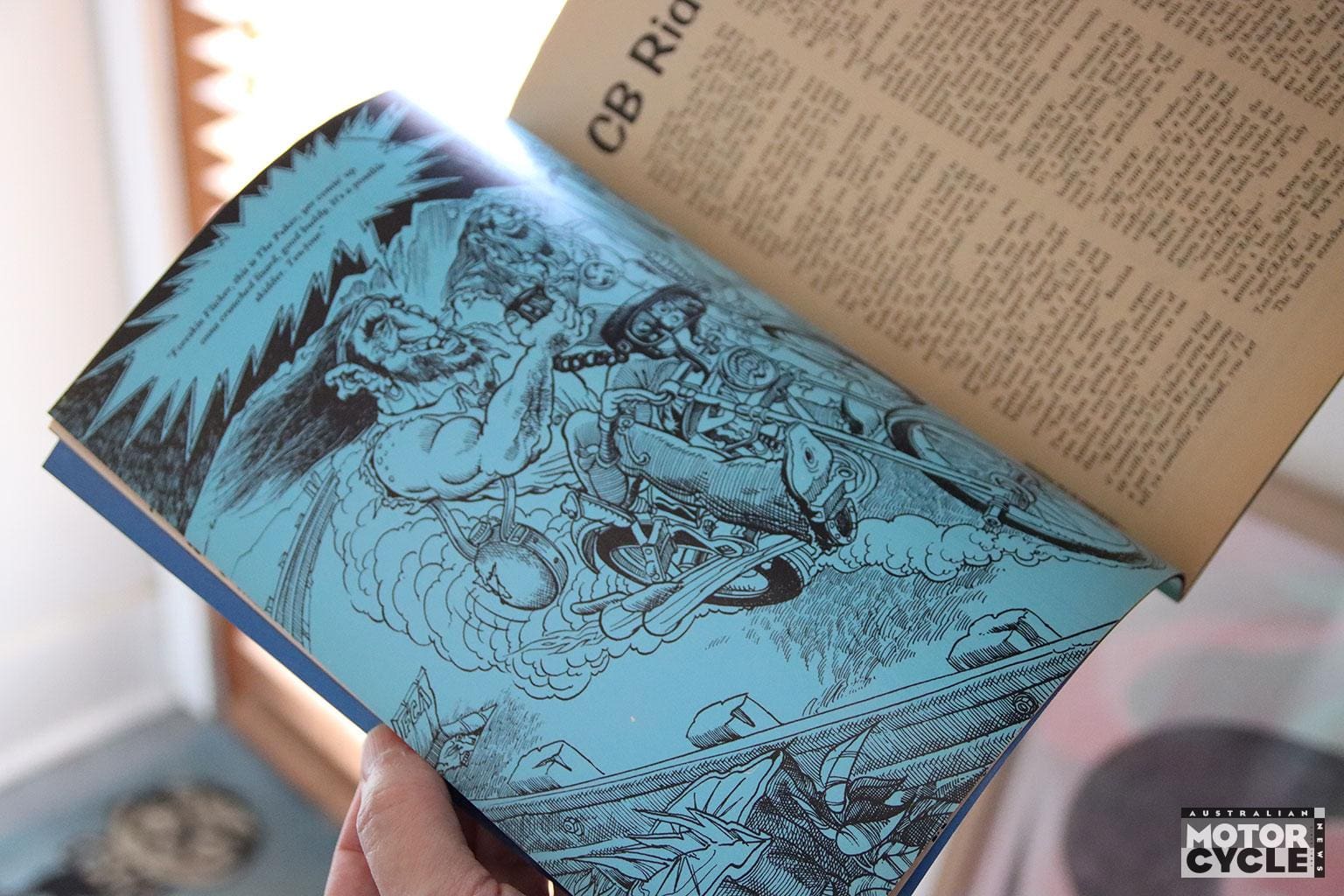

His most iconic creation, Terry, started as a biker version of a Sailor Jerry-style tattoo and it’s since taken on a life of its own.

“I didn’t expect it to take off the way it did, but yeah, he’s just become a thing.”

So much so that Russell’s currently working on a comic book based on Terry and his fictional motorcycle club, the War Buzzards.

“I realised I had all of these characters, that I’d drawn this out for something, this up for something else, I’d drawn patches and… well maybe all these guys just ride for the War Buzzards?,” he says.

“And I’ve been collecting stories from one of my neighbours who passed away recently. He was a one percenter back in the 1970s down in Geelong.

“Like serious proper, he did time in Pentridge and everything, he used to tell me a lot of stories about ‘back in the day’. So some of those stories are going to

be retold, but as Terry and

his club.”

Brush and ink

Russell has owned 33 motorcycles in the last 30 years. These days he gets around on a couple of premium European offerings, in fact the latest acquisition was previously owned by Carl Cox.

“I had a 1979 Sportster; all hardtail, full chopper, tiny little tank and all that – a ground-up rebuild,” he says. “But every time I’d pull out of here I’d get pulled up by the Highway Patrol, who’d keep me on the side of the road for 40 minutes, defecting me for whatever they could find. Then I’d get up to Moorooduc (10 minutes away) and another guy would pull me over. I’d say I just got done, and it was ‘Yeah, don’t care mate, we’re doing it again.’

“Now I have a stock bike and no one can hassle me. I love choppers but, for me, if I have to ride every day and I have to be doing stuff, it makes it difficult.”

Despite Russell’s formative years in computer graphics for rudimentary video games, his selling point these days, and the thing he’s extremely proud of, is all of his work is done by hand using brush and ink.

“I hate digital, I don’t want to do digital, I have no interest in it whatsoever – it’s too easy,” he states. “You do analogue stuff, you commit to it. You put that brush to the paper, you make a mistake, you’ve committed to that line.

“Tattooing was great like that – you make a mistake in tattooing, you’re committed to that and you have to work with it.”

It’s a stance that, while admirable, adds complexities to the realities of making a living from his art. As well as being more time consuming and more expensive both to produce and to purchase his work, accepting the many invites he receives to be part of international exhibitions or custom bike shows is difficult. Because what could otherwise be a simple file transfer is now an expensive process of framing, packing and shipping. A process, says Russell, that’s not often worth it when all’s said and done.

Artistic process

Despite this, Russell’s work has taken him across the world. He’s exhibited and judged custom shows in Malaysia, Thailand, Italy and Finland as well as here.

The Sturgis Rally poster – a pinnacle of his commercial work – has become particularly significant, even winning an advertising award with his first-ever poster design.

He shows me the final design for the 2025 poster, but I’m not allowed to take pictures of it because it’s all still under embargo ahead of the August 2025 event. But it’s fascinating to see the final design of an intricate and organic process that literally starts with a few words.

“The guy who runs their marketing is really into science fiction and films,” he explains, “So he’ll send me a message, give me a few keywords and then I take that away and sit on it for a while. I’ll do a little sketch here and there. I leave it for a couple of weeks and then I come back to it and it sort of pops out.

“I’ll send him a basic pencil drawing. Then it gets drawn in parts, really rough, then it gets fleshed out bit by bit. You know, we start to put in the basic shapes, motors, things like that. Figuring out how exhausts run, all that sort of stuff. And then I’ll actually draw the motors and everything completely separately to everything, so I’ve got the lines right.

“And then it all gets dropped in,” he continues, as we move towards another poster so he can illustrate his next point. “And you actually end up just obliterating most of it too, because behind his leg, all that motor was drawn at one stage. So we’ve got all the transmission and everything (behind) there.

“Same on this side,” he says, pointing to another image. “All of the kicker pedal was there because sometimes, once you put the leg in, there might just be a little hint of it, but I need it to still line up properly. I want to make sure it’s correct – and not just correct, but it has to be correct for a (Harley-Davidson) Shovelhead.”

I ask him what his favourite piece of artwork is and he turns to another Sturgis poster.

“This was the first piece I did for Sturgis,” he tells me. “So the band here is ZZ Top. Unfortunately, one of the band members died just before the show and I was like, ‘Oh shit’. Got the kiss of death.

“But yeah, that’s one of my favourites. It just has this wild, psychedelic feel to it, like it’s impossible. I like working on things that are impossible.”

He points to another, which has a similar look and feel to the previous two.

“Oh, this was another really popular one. That one’s called Crystal, because (of the) crystal ball. Look, there’s a whole bunch. I mean, I could go through here and I’d probably find you 20 or 30 that I really love.”

And love’s a really good word. Because you don’t need to spend a lot of time in Russell’s presence or in his small and colourful studio space to really understand that he truly loves what he does. It’s honest and it’s authentic, but it’s the way he can illustrate and celebrate the feelings and the emotions motorcycling ignites in all of us that makes Russell’s work so enchanting.

You might know him as “Mow”

It turns out, any illustrator who’s anyone has a pen name, and Russell’s is Mow, pronounced like meow but without the e.

“Everyone has to have a name,” he explains. “Like Coop, you know, and Rockinjelly Bean. Back in the 80s, I got some junk mail one time from Singapore and it was addressed to Mr. Lussel Mowchai, like a bad stereotypical version of Russell Murchie.

“So I started using Mowchai in video games, you know, when you’re playing online and stuff, and then it became Mr. Mow. And now I just use Mow.”

Want some?

Russell has a collection of his work available for sale on his website, ranging from hand silk-screened limited-edition prints, stickers, T-shirts, cast parts and even original artworks. Just like his hand-drawn approach, another thing he’s particularly proud of is that all of his products are produced in Australia.

“Even though it costs a shitload more,” he nods.

Follow him on Instagram via russell.murchie, on Facebook under Russell Murchie or check out his wares at mrmow.bigcartel.com