With automatic transmissions gaining popularity in the motorcycle world, AMCN’s Ben Purvis asks, is the manual transmission heading for extinction?

History shows that when an easier way of performing a task comes along it’s only a matter of time before the previous method is all but forgotten. When was the last time you wrote a letter rather than an email? Played a CD instead of streaming an album? Added an address to your Rolodex?

It’s the same for automatic transmissions on motorcycles. The carburettor is all but extinct. Kickstarting is a nearly forgotten art. And perhaps in the not-too-distant future the choreographed interplay of a hand-operated clutch and foot-shifted gears will be similarly anachronistic, because automatic and semi-automatic motorcycles are on the verge of hitting the mainstream in a big way.

Self-shifting two-wheelers have been tried before, of course. The Hondamatics of the 1970s, for example, as well as various attempts at integrating constantly variable transmissions (CVTs) into big bikes or blurring the lines between scooters and motorcycles by shoehorning ever-larger engines into step-throughs. But with the notable exception of the scooter market, where pulley-based CVTs have been the norm for decades, most of these efforts have attracted few customers and motorcycle companies have rapidly retreated to the familiar territory of sequential manual transmissions.

Now that’s changing. BMW, Yamaha and KTM have all announced plans to add semi-auto models to their 2025 line-ups, each using a variation on the theme of adding electromechanical actuators and computer control systems to conventional sequential manual transmissions. That’s a smart move in terms of tech, cost and marketing. From the tech side it means that large numbers of components can be shared across both manual and automatic bikes, with the main mechanical elements already being tried-and-tested kit that isn’t likely to fail. That impacts cost as well, reducing the amount of retooling required, making it easier to produce manual and auto models on the same production lines, and vastly reducing the risk of expensive recalls due to unexpected failures.

And marketing? That’s perhaps the most important aspect. After all, automatics in cars are associated with a lack of involvement, a lack of enthusiasm, and there’s a similar feeling that real riders shift their own cogs. By making manual-based semi-auto transmissions, they can be labelled as ‘automated manuals’ – a natural progression from race-style quickshifters rather than a lazy, labour-saving device.

We see it in the terminology that the companies are using. BMW’s new transmission, which has electromechanical actuators to operate the clutch and turn the shift drum, is called the Automated Shift Assistant (ASA). Not automatic, you’ll notice. It’s an assistant, firmly reminding you that it’s you, the rider, who’s in charge.

KTM is playing the same game. Its auto ’box works on a similar principle but given the title ‘Automated Manual Transmission’ (AMT). And Yamaha’s set-up, which has external actuators for the clutch and shifter acting on a resolutely conventional six-speed ’box, takes the same path as ‘Y-AMT’ for ‘Yamaha Automated Manual Transmission’. The emphasis on ‘manual’ makes sure we’re aware that these are still proper gearboxes for grownups, not some sort of safety net for people who can’t be trusted to juggle a clutch lever and a foot shifter without stalling or banging heads with their pillion passenger at every gearchange.

Yes, they have manual modes. BMW is even hanging onto a foot lever to carry out the gearchanges, albeit via electronics instead of shafts. Yamaha, meanwhile, has ’bar-mounted paddles inspired by the shifters on racing cars, and KTM takes a similar route, with a thumb-operated ‘up’ shifter and finger-controlled ‘down’ trigger. From a rider’s perspective, providing the all-important computer programming is right and the synchronisation between the clutch and shift actuators is correct, the result should be nearly seamless changes, while pulling away and stopping should be similarly painless thanks to a computer-controlled clutch.

Each design also has at least one mode where the computer controls the shifting as well, though, so regardless of the terminology their makers use, these have the ability to operate as fully automatic transmissions.

Why now?

The technology to automate a motorcycle’s clutch and sequential transmission has been around for decades. Yamaha did it on the FJR1300 in 2006, after all. So why is there suddenly such a rush to adopt the idea across an array of motorcycles from major manufacturers?

To find the answer, we need to look to Honda – a company that’s already taken multiple shots at the goal of creating viable automatic motorcycles, and for whom that effort is finally paying off.

Back in the 1970s, when the Hondamatic transmission was offered on a range of models from 400cc to 750cc, the company had already hit upon a non-traditional approach of trying to make motorcycles appeal to non-riders. The Cub – another semi-auto – and its associated advertising proclaiming “You Meet the Nicest People on a Honda” illustrated clearly how Honda wanted to appeal to people who weren’t interested in the grease-and-leather image of bikes at the time. Even as far back as 1949 and the introduction of the Honda Dream D-Type – the company’s first real motorcycle – Honda appreciated that the challenge of operating a clutch and gearshift separately was a hurdle to inexperienced customers, so combined the two into a single pedal and a two-speed transmission.

In that post-war period, scooters took off around the world as people with no interest in the mechanics of riding motorcycles adopted them as simple transport. That was also thanks to the fact they didn’t have the complication of a clutch and gear shift to control.

Despite all the evidence that there’s a pool of potential riders turned away by the hurdle of clutch and gear control, it’s proved hard to tap into that market – hence the lack of enthusiasm in the past for semi-auto boxes. But over the past 15 years that’s changed thanks to Honda’s clever-but-complex DCT.

DCT is probably the most complicated motorcycle gearbox ever to reach mass production. It’s easiest to think of it as not one but two gearboxes, each with its own gears and clutch. One of those transmissions deals with the odd-numbered gears and the other with the even-numbered ones. Since each can be connected or disconnected from the engine via its own clutch, both can simultaneously select gears. In practice it means that if you’re in first, the bike knows your next ratio will be second, so it preselects that gear and when the shift is triggered it only needs to release one clutch and engage the other to complete the gearchange. It’s silky-smooth and, unlike almost any other transmission, it’s truly ‘seamless’ with not even a second when drive to the rear wheel is interrupted.

DCT was introduced with the VFR1200F in 2009 but it was a rocky start. Despite being a technological triumph and marking Honda’s return to the V4 engine configuration that it was once synonymous with, the VFR1200F wasn’t a success. It was a mild-mannered sports-tourer when customers wanted either a fire-breathing superbike or a go-anywhere adventure machine.

DCT is also heavy, clocking in at around 11kg, complicated and expensive. Not only does it add an extra clutch and require a completely different transmission, it’s operated via a combination of electronics and hydraulics rather than using electricity alone. On the face of it, back in 2009, it had the makings of becoming another intriguing hiccup in Honda history – something that might appeal to collectors many years later but not a mainstream success.

But the company persisted. DCT was offered across the NC700 and NC750 model ranges, finding success among riders who prioritised practicality over performance, and has since spread to the Goldwing as well as the CMX1100, NT1100 and, most importantly, the Africa Twin.

And the customers came for them. Despite its high cost and added weight, across the models offered with the choice of either DCT or manual transmissions, the semi-auto box accounts for around half the total sales. On some models, like the Goldwing, it’s become dominant and Honda says that in Europe alone, since the introduction of the tech in 2009, it’s sold more than 240,000 motorcycles with the DCT option.

For a while other bike companies could only look on in envy. Honda had ploughed a fortune into the R&D of the DCT transmission and holds a fistful of patents around the idea, making it prohibitive for rivals to jump in on the semi-auto action. The likes of BMW, Yamaha and KTM will have been wondering how many of those Honda customers opted for an Africa Twin or NC750 purely because of the semi-auto option.

What’s more, if around 50 percent of customers are prepared to pay the hefty premium that’s required to buy a DCT bike, and to put up with the extra weight that it brings, how many would be tempted by a cheaper, lighter solution that offered most of the same advantages?

Now that’s possible to achieve thanks to a convergence in technology. Today’s bikes have more on-board computing power than ever before allied to such tech as ride-by-wire throttles and a vast array of sensors monitoring throttle position, speed, lean angle and dozens of other parameters. All this can be combined with relatively simple but fast-moving electromechanical actuators and clever computer programming to achieve lightning-fast automated gearshifts and smooth clutch actuation that mimics the seamless shifting of DCT at a fraction of its cost and complexity.

What’s coming for 2025?

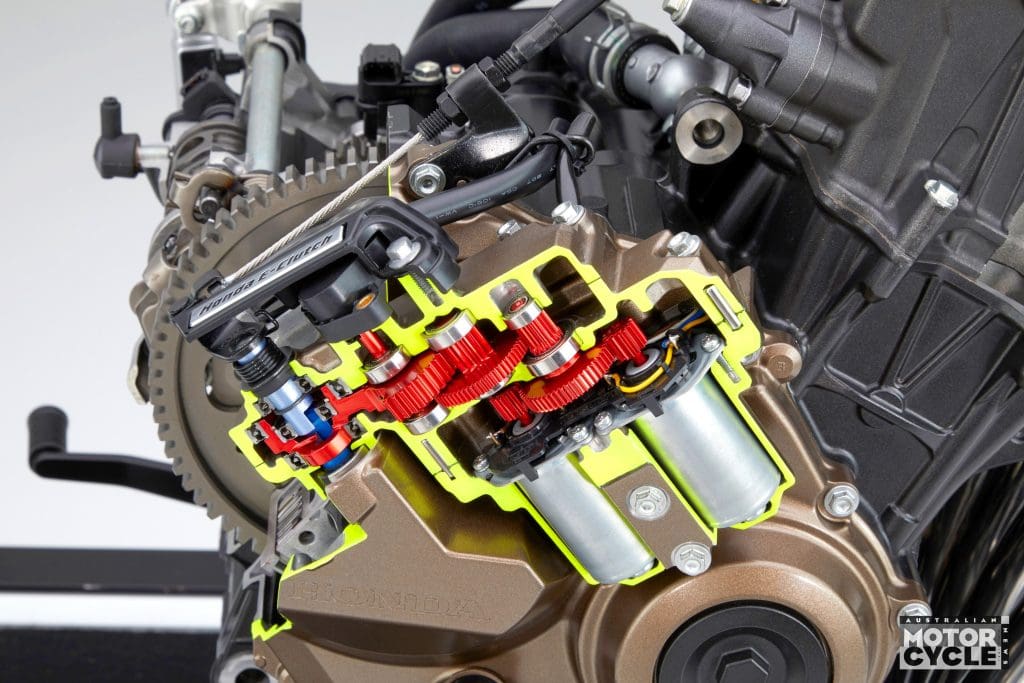

Honda, like its rivals, has appreciated the potential of a low-cost alternative to DCT and this year added the E-Clutch as an option to the CB650R and CBR650R. Although not a semi-auto transmission, as the foot-operated gearshift is still mechanical, the E-Clutch is an intriguing halfway-house to a proper semi-auto ’box.

As an option, its price is around a 10th as much as DCT, and Honda’s clever design means that there’s still a clutch lever even though you don’t have to use it. If you want to operate the bike manually, you can. Combined with the low cost, that means even customers who aren’t really bothered about the system might well tick the ‘E-Clutch’ box simply because it adds so little to the price and might help make it more appealing when it comes to selling the bike down the line.

Although the E-Clutch has so far only been seen on those two models, there’s a strong possibility that Honda will add the option to more bikes in 2025. That’s because it’s essentially self-contained and relatively simple, needing just a new clutch cover that contains the clutch operating actuator, plus some new computer coding to integrate it to the bike. Almost anything in Honda’s range could, potentially, be offered with E-Clutch in the future.

BMW’s ASA system has already been announced and will be offered on the R 1300 GS and R 1300 GS Adventure in 2025. It’s a bit more involved than the E-Clutch, with internal changes to the transmission to accommodate an actuator to shift the gears and another to hydraulically control the clutch. Logically any future model using the new 1300cc boxer engine is likely to be offered with the system – like the R 1300 RT tourer we spied last issue.

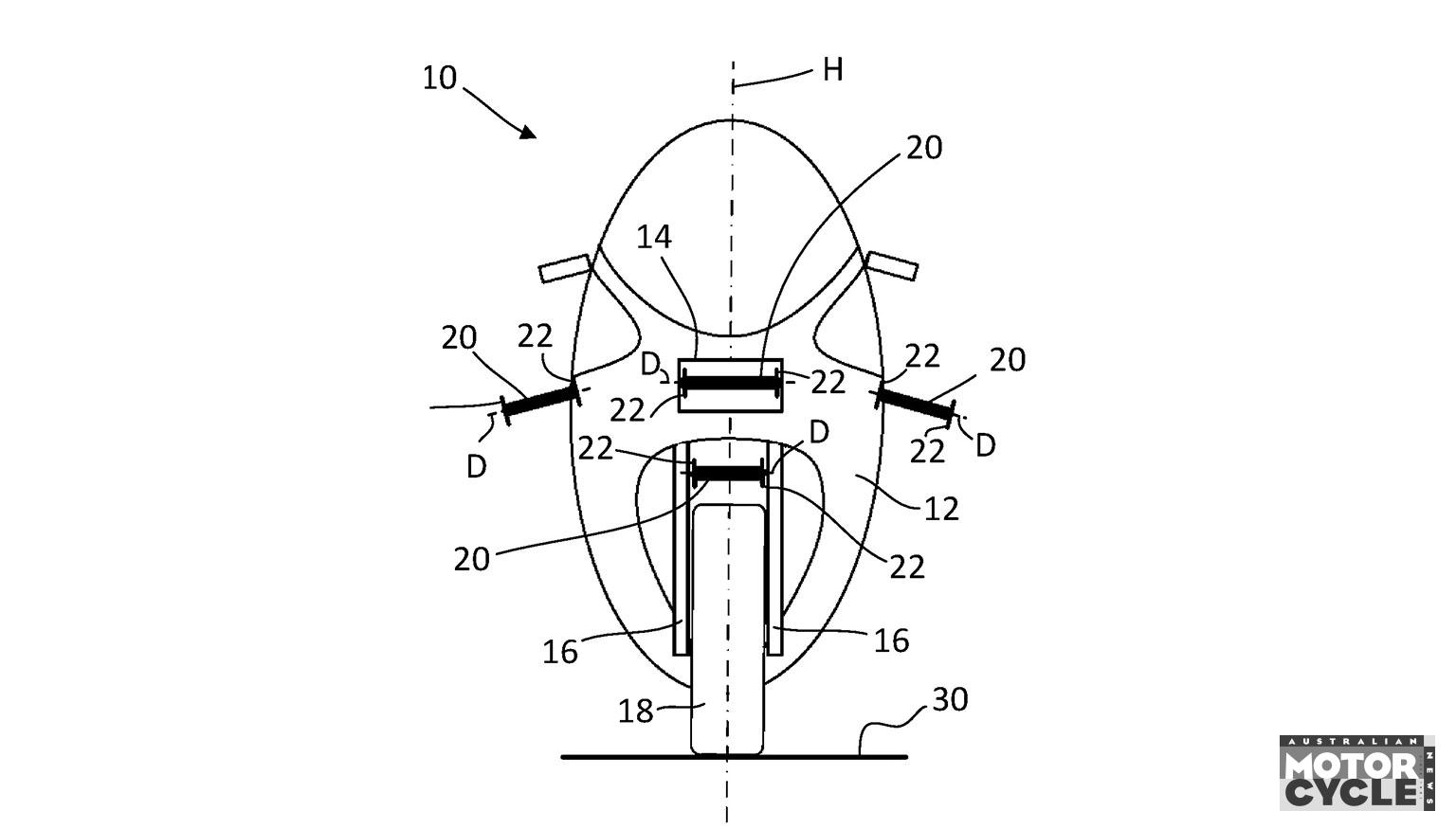

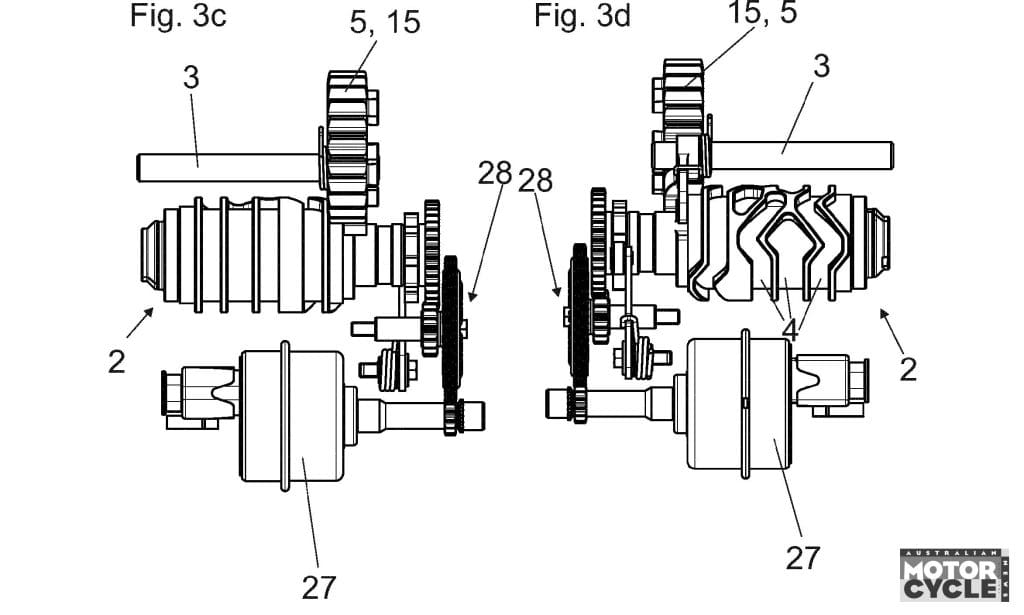

Yamaha has officially announced that its Y-AMT transmission will be offered on the 2025 MT-09 in 2025. Its patents have also shown that the MT-07 and R7 are to be reworked for 2025, with cooling for a new computer unit – the Y-AMT controller – as a key element of the changes. With the system being offered on both the 689cc parallel twin engine and the MT-09’s 890cc triple, all the models using those engines, including the Tenere 700, Tracer 7 and Tracer 9, XSR700 and XSR900, and the Niken three-wheeler, are potentially in line to get Y-AMT as an option.

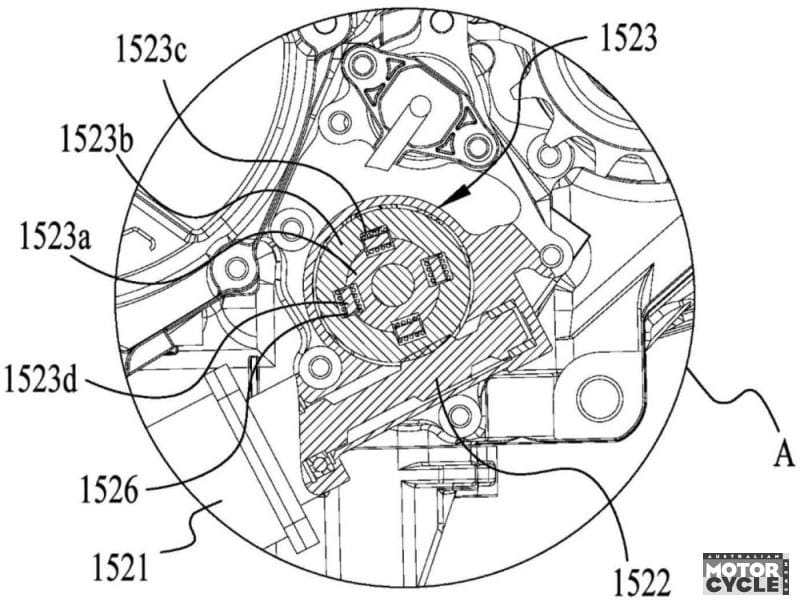

Less is known about KTM’s AMT system at the moment, other than the fact a prototype for the new 1390 Super Adventure was run at the Erzbergrodeo with the system fitted, and that the company has filed patents for a notably different style of semi-auto ’box. Like the Yamaha and BMW designs, the KTM patents show a transmission with an electromechanical actuator to operate the gearshift, but instead of a similar actuator on the clutch they suggest the KTM design has a centrifugal clutch. That means the clutch will automatically disengage when revs drop below a predetermined level, making starting and stopping simple. But it also required the development of a transmission locking system to work as a parking brake when the bike is unattended.

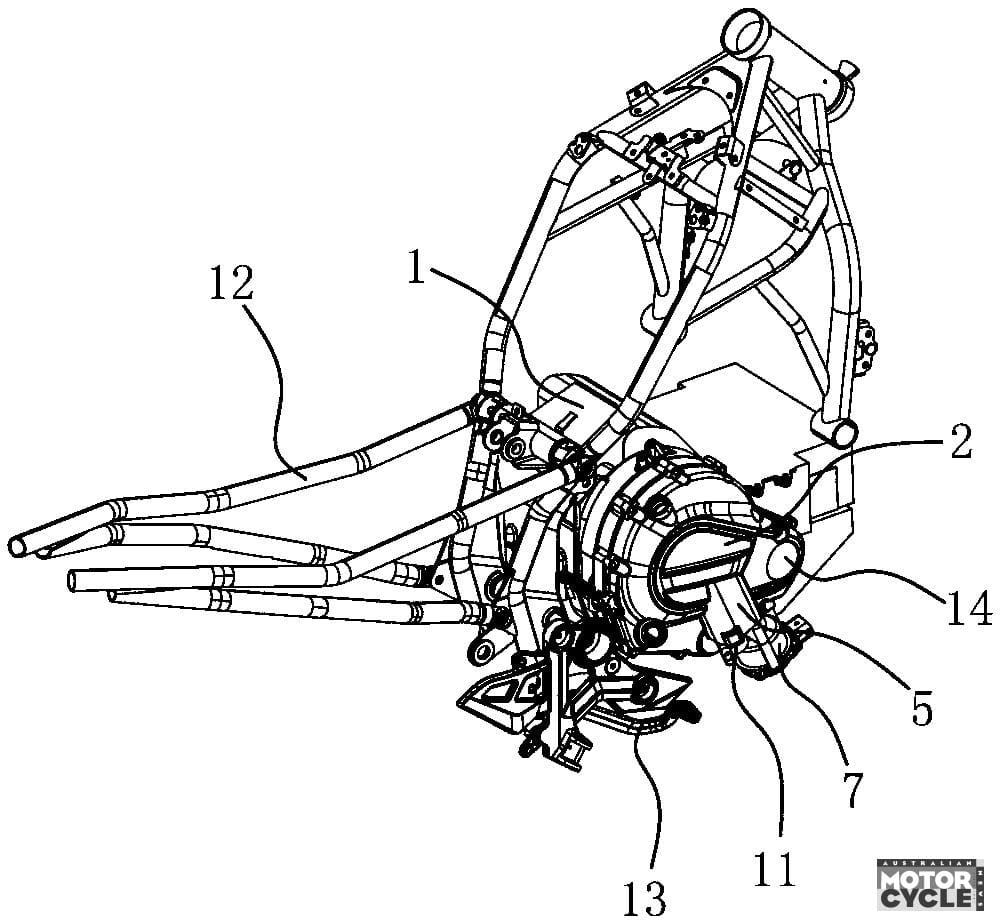

We also know that several other companies are working on their own systems and China’s CFMoto is one of those. The brand has applied for patents on elements of a semi-auto transmission, illustrated on the 693cc parallel twin of the 700CL-X in the patent documents. Another fast-growing Chinese brand, QJMotor, has also filed patents for its own version of the same idea.

Kawasaki, meanwhile, also has an existing semi-auto, albeit used in harmony with its unusual petrol-electric hybrid system in the Ninja 7 Hybrid and Z7 Hybrid. The transmission itself is essentially similar to the BMW and Yamaha designs, with automation for the clutch and gearshift, but with the added complexity of being able to blend in power from the hybrid system’s electric motor. We know Kawasaki has more hybrids in store, with the same transmission, as both a Versys 7 Hybrid and an Eliminator 7 Hybrid have been subject to patent applications filed by the company.

What’s the future for manuals?

With a revolution in semi-auto bikes on the horizon the question might soon not be whether semi-autos can be successful but whether conventional manual transmissions and clutches still have a future.

We’ve already seen this happen on four wheels. While true automatic cars, with torque converters and auto ’boxes based around epicyclic gears, have been sold alongside manuals for decades, over the last 20 years or so the automated manual has come to the fore. In high-performance cars in particular, automated manuals – often with dual clutches like Honda’s DCT – have all but replaced stick shifts and foot-operated clutches. Neither Ferrari nor Lamborghini have made a manual production car for over a decade, and the latest Porsche 911 is the first to be launched without the option of a stick shift.

That’s in part because car racing has embraced the semi-auto since the 1990s, meaning customers who want something with the look and feel of a racer also want a semi-auto shift. That’s not the case for motorcycles. Semi-autos are specifically outlawed in MotoGP and the fact that riders are, by definition, enthusiasts means that the conventional clutch and shifter are likely to be here to stay for many years yet.

In fact, at just the same time that BMW, Honda, Yamaha, KTM and others are putting a focus on the development of semi-auto transmissions for ICE bikes, more than one brand is working on ways to add the involvement of a clutch and shifter to future electric models. Kymco, which is working with Harley-owned LiveWire on a future generation of EV bikes, has developed an electronic clutch and shifter, changing the power delivery and engine-braking effect to replicate a conventional manual transmission and its controls, even though it actually has a single-speed, direct-drive gearbox between the motor and rear wheel. Californian electric bike pioneer Zero is also developing a similar idea for a faux clutch lever to give riders a more direct control over acceleration and engine braking than they can achieve with a throttle alone.

Beyond that, we know that while the biggest-selling large semi-auto bikes on the market now – Honda’s DCTs – account for around half the sales of the models the system is offered on, that means the other half are still choosing the standard manual transmission. No company is going to willingly opt to deprive themselves of that market by switching to an all-auto model range.