The Bell full-face helmet was born on the dirt-tracks of America

Al Gunter was a successful AMA motorcycle racer of the 1950s and ’60s. He was also credited with inventing, developing or influencing the following: hardened-and-cut tyres for better grip on dirt tracks; blended-and-raised valve seats that increased air flow in the cylinder head; pistons and carburettors machined from billet; and dynamometers as a race-engine development tool for privateers. And on top of all that he played a central role in the creation of the full-face helmet.

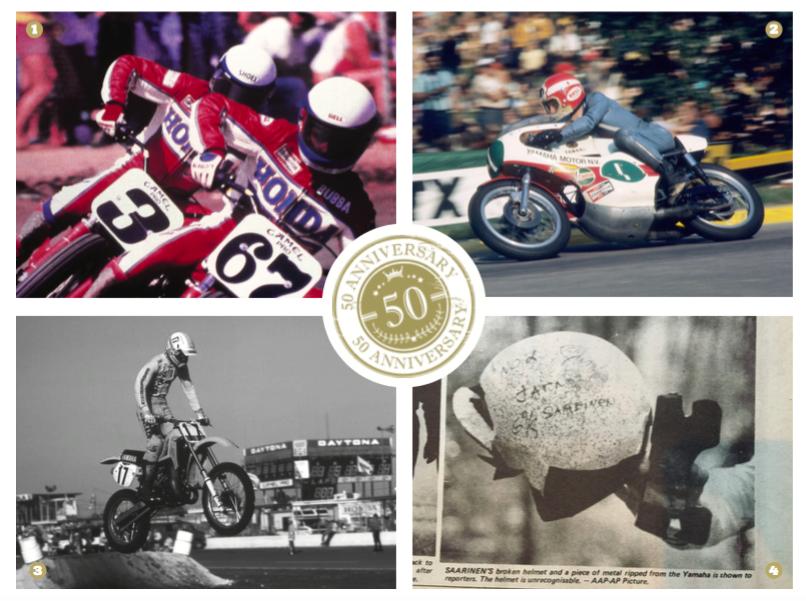

One freezing night at Ascot Park Raceway in Los Angeles in 1963, Gunter appeared on the grid with a bespoke full-face helmet, the world’s first public showing of the space-like design. “Get a load of the helmet Number 3 Al Gunter is wearing!” bellowed legendary race announcer Roxy Rockwood.

Gunter later pushed Bell Helmets founder Roy Richter to develop the full-face helmet, to provide even more protection than Bell’s game-changing open-face ‘jet’ helmet introduced the previous decade. The resulting fibreglass-shelled Bell Star developed in 1966 became the world’s first commercial full-coverage helmet.

AMA champion Dick Mann was part of the project, and had plenty of input. “Al Gunter, Neil Keen and I were some of the first motorcycle racers wearing and testing the Star helmets,” Mann recalls. “The professional racers welcomed the new helmet, but were concerned about the visibility and the claustrophobic nature of the full-face design. I voiced my opinion on these two subjects to Al. They then started opening the window of the face mask, and that helped. I came up with a flip-up shield on my helmet that nobody else had. I made mine out of fibreglass that had a removable plastic lens. I used that for years. In the beginning, Bell refused to put that option on its helmets. Later it came up with the full plastic flip-up shield.”

The first major public showing for the full-face was also its first real test. Evel Knievel wore a Bell Star at Caesar’s Palace in 1967 when he crashed attempting a televised 43-metre jump and suffered a crushed pelvis and femur, and fractures to his hip, wrist, and both ankles. Coming up short on the jump over the Palace’s fountain, Knievel was launched over the ’bars at 130km/h, the back of his helmet whiplashed hard into the asphalt causing him severe concussion. As he rolled into the Dunes casino carpark, the chin-bar prevented serious facial injuries. Knievel later credited the helmet for saving his life.

American car racer Dan Gurney had experimented with open-face jet helmets in his early racing days and made a leather mask to cover his face, an idea that later found favour in speedway. The mask was designed after Gurney – like Gunter and fellow bike racers – was repeatedly hit by small stones thrown up from the track.

“I was racing a 4.9-litre Ferrari and I was trying to overtake a car ahead of me, which fired a stone from under a rear tyre,” remembers Gurney. “It went right through the windscreen. It was more akin to a bullet than a pebble.”

Dan wore the mask in some open-wheel races in 1962 but never felt quite comfortable and gave up on it. It wasn’t until he went to watch Gunter, Mann and Keen at Ascot Speedway that he found a solution already in use. In dirt-track racing, the problem of flying stones was even worse (“Like a firehose full of them,” said Gurney) and the riders had an altogether superior defence against it: the full-face helmet. Introduced by Bell Helmets, it extended the protection under the eyes, over the nose and mouth, and down to below the chin.

Although Gurney wasn’t the first to wear a full-face helmet in a racing car – his protégé David ‘Swede’ Savage, an ex-bike racer, beat him to it in 1967 – He did bring the design to the world’s attention when he wore it for the first time at the Indy 500 in 1968. Then again at the wet German GP at the Nürburgring a couple of months later.

In the years that followed, Gurney worked with Bell to develop the full-face helmet for car racing. He was at first ridiculed, but within months other drivers adopted the full-face helmet and now we cannot imagine how they ever raced without them.

The Bell Star was officially released in 1968 and imported into Australia a year later by champion driver Frank Matich. The late racer’s son, Kris, who worked in the business, recalls: “The main market was motor racing, which wasn’t that big. In the early 1970s compulsory helmet laws for motorbike riders were introduced, so we began distributing Bell through motorcycle dealers across Australia. The dirt-bike boom took off as well, so that was another market we could target with the launch of the Bell Moto Star in 1975.”

The world’s first full-face helmet was a revelation, and Bell (even though it was named after a suburb in Los Angeles) was the perfect brand name for the space-age design, evoking an image of a bell with a viewing portal. It made perfect sense. Protecting the jaw and face was obvious, why did it take so long? It was a hit in open-wheeler racing and motorcycling both on and off the track; the Bell Star looked cool, modern and brilliantly functional.

When a typical field of road racers swept around the track in the early 1970s, the full-face helmets were already outnumbering the old open-face models, which looked positively dated and exposed in comparison.

Nevertheless, there were questions raised about the safety of heavier full-face helmets. Promising South Australian speedway rider Laurie Hodgson was left a paraplegic after a

multi-bike crash at Rowley Park in February 1971. The 24-year-old father of three had represented Australia in a Test series against England and was about to pursue a career in the competitive English speedway league.

Following Hodgson’s crash, the controlling body of South Australian motorcycle racing, the ACU (SA), banned the use of full-face helmets claiming they were involved in six fatal or near-death incidents where the rider sustained neck injuries. The ban was based on a report by the St John Ambulance delegate to the ACU, who claimed that by the “nature and weight of the full-face helmet and closeness to the chest and shoulders, caused a whiplash-type injury in some circumstances resulting in damage to the vertebrae in the neck”. The report claimed the helmet was flung forward until the chin guard hit the wearer’s chest, which then acted as a pivot point. The St John delegate based his reports on the SA accidents, but also information on accidents in other states.

The issue went national when the Auto Cycle Council of Australia considered a national ban. Bell agent Matich provided advice from American expert George Snively of the Snell Foundation, the world’s leading helmet authority. Dr Snively reported there had been 370 crashes where a Bell Star had been involved and “there was no need for concern”.

He acknowledged that full-face helmets could cause broken collarbones, but that it was like receiving an abdominal injury from a seatbelt; it was a better to sustain a serious injury rather than a critical one. In conclusion, he said he would “lean towards more protection even it meant an increased weight of the helmet”.

The timing of the inquiry was interesting. Australia’s most populous state, New South Wales, was about to make helmets compulsory for all motorcycle riders on 1 August 1971, but the controversy raged for more than a year. Nevertheless, full-face helmets were not banned from racetracks. Increasing numbers of road riders began buying them and customising them with paint jobs and stickers.

Now we can’t imagine the world without them.

By Darryl Flack