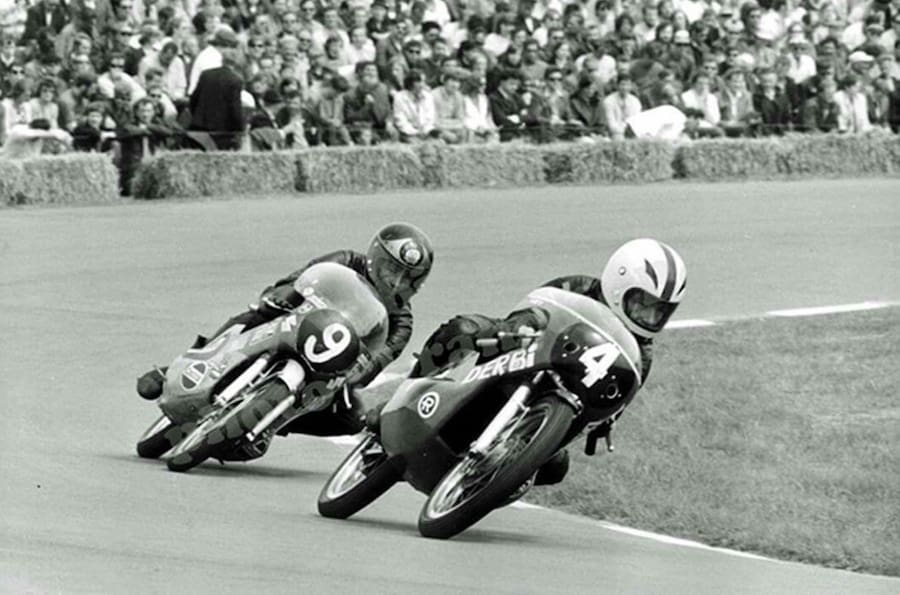

Ángel Nieto once triggered two racetrack invasions in a day at Jarama, near the Spanish capital of Madrid. The first because he crashed trying to clinch the world 50cc championship, the second when he won the 125cc grand prix, and with it the title. Nieto was 24 and the man he beat for the crown was Barry Sheene, just turned 21, on a privately entered Suzuki.

Nieto had crashed in the 50cc GP trying to keep pace with his rival for the title, Jan de Vries on the faster Van Veen Kreidler. He suffered a badly cut leg, but was stitched up in the local hospital without anaesthetic so he could continue racing that day. He returned to the track to beat Sheene and Yamaha rider Chas Mortimer to win the 125c race and world title, after somehow executing the dead-engine push start. His victory caused total chaos, with thousands of fans invading the track as soon as he crossed the finishing line; hundreds of firecrackers swathed the circuit in smoke while other riders were still racing (see breakout).

The year was 1971 and the reaction from the huge crowd gives you some idea of Nieto’s stature in Spain at that point.

He was a national hero and the motorcycle racing trailblazer the country needed, beating the odds on several scores, including his background, the ultra-dangerous circuits, and a shortage of quality racing equipment and factory support in the country’s buttoned-down Franco era.

“After winning that Jarama race, that’s when I really got very popular,” Ángel said recently. “It was front page news on all the Spanish newspapers, and after that I was no longer someone who went unnoticed walking down the street. I was on TV every day, talking about what I liked to eat, which clubs I went to, where I went at weekends. Before I was a sportsman, but after that I was a celebrity.”

The ’71 world title was Nieto’s third, after becoming the first Spanish world champion in 1969. He would go on to win 90 grands prix and 13 world crowns – or, as the superstitious superstar always insisted, 12+1.

Now he is gone, at age 70.

Nieto died on 3 August 2017 after sustaining severe head injuries when struck from behind by a car while riding a quad bike near his home in Ibiza. It is safe to say we’ll never see his like again, on several scores.

Born in Zamora in 1947, Nieto was raised in a tough part of Madrid that resulted in his first racing nickname: The Vallecas Kid. His contemporary, the 1969 world 250 championship contender Santiago Herrero, hailed from the same area.

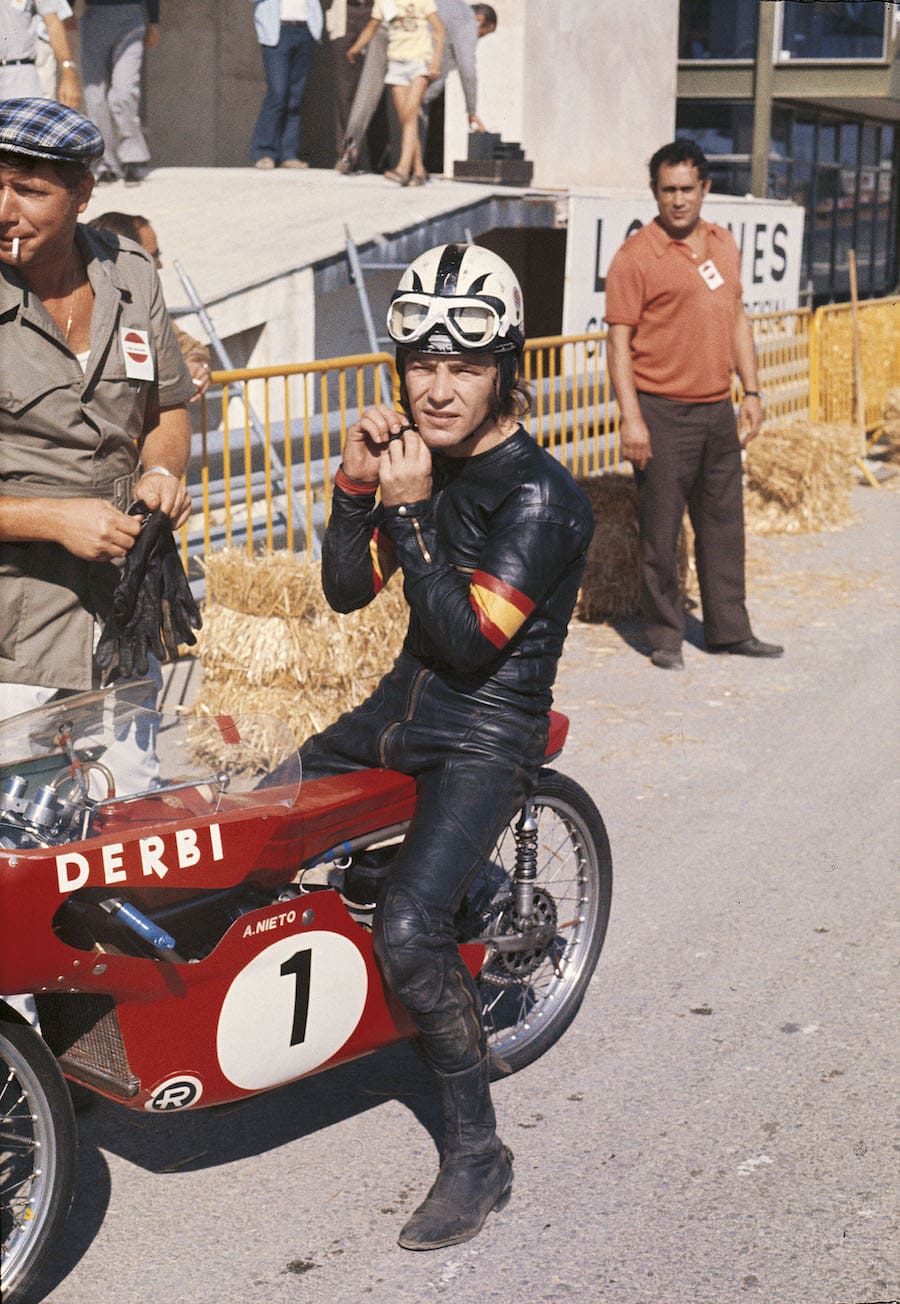

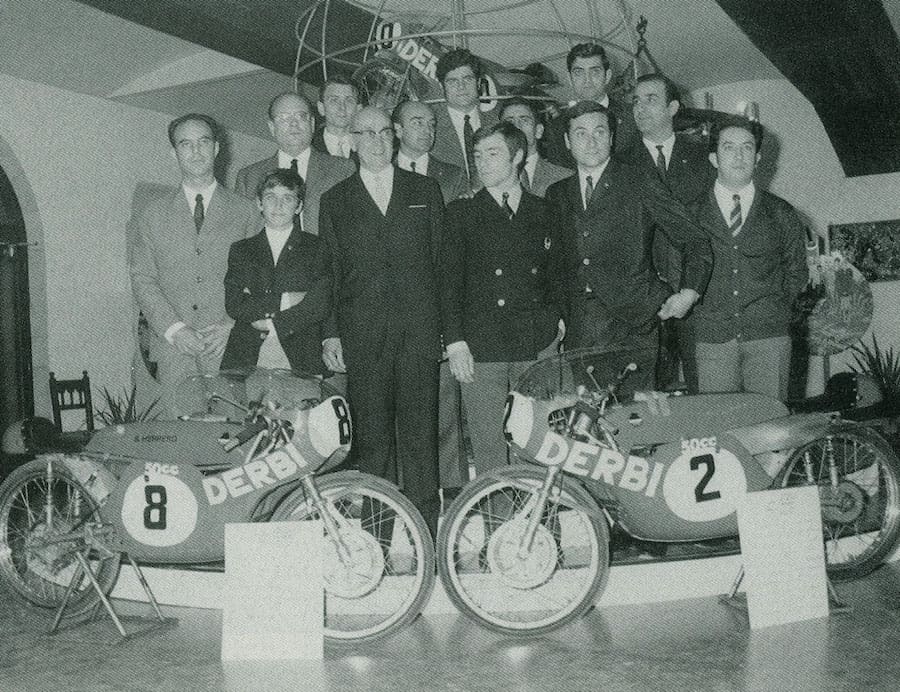

At just 12 years old , Nieto was already an apprentice motorcycle mechanic. Legend has it he would take to the streets on customers’ 650 British twins when his boss was away. He started racing early, riding a Derbi on street circuits and hillclimbs.

From the perspective of MotoGP today, Spanish racing in the mid-1960s might as well have been on a different planet. Spain currently hosts GPs at Aragón, Catalunya, Jerez and Valencia, and supplies 40 per cent of the MotoGP field, but a teenage Nieto raced on dusty street circuits around city parks (including the famed Montjuïc in Barcelona) and industrial areas. Hazards included kerbs, poles, walls, minimal spectator control and wandering dogs.

Spain’s motorcycle companies were centred in Barcelona, 12 hours by road from Madrid, and that was Nieto’s next port of call. He signed with Derbi in 1964 and at age 17 scored championship points by finishing fifth in the Spanish 50 GP at Montjuïc Parc.

The following year, on a rare trip outside Spain, Nieto was fifth in the West German 50 GP on the Nürburgring Südschleife or South Circuit. The weather was terrible and the track slippery. (Nieto in the 1970s had an impressive record at the full Nürburgring, winning three times in all types of weather.)

Franco-era import restrictions hampered Spanish riders, especially in the 60s. Japanese factories couldn’t sell roadbikes there, so didn’t want to hire Spanish riders. Derbi and the other Barcelona-based factories couldn’t source quality materials and accessories. Australia’s Barry Smith helped out when he joined Derbi, by slipping equipment past the border guards in his van.

And then there was the level of competition in the mid-60s world championships.

Honda, Suzuki and Yamaha were in earnest battle. Want more power? Okay, make more cylinders. Suzuki had a three-cylinder 50 under development. However, at the end of 1967 Honda and Suzuki folded their works tents, and Yamaha withdrew a year later.

Dovetail this with an FIM rule change limiting 50s to one cylinder, and 125s to two, and Derbi was there with its painstakingly developed machines. Smith and Nieto started winning GPs, against mainly Dutch opposition.

In the 1970s, Nieto worked with Dutch engineers, including the famed Jan Thiel, and later Germany’s Jörg Möller, as he rode for various makes. He was soon dubbed the King of the Tiddlers – specialising in 50s and 125s. The only other small-bike exponent to dominate an era in that way was Italy’s Carlo Ubbiali, who was nine-times champion and won 39 GPs in the 125 and 250 classes between 1950 and 1960.

Nieto, however, had been Spanish champion in 250, 500 and even 750, and had ambitions to win world crowns on larger machines.

He didn’t ride 50cc bikes from 1973 to ’75, and in 1976, while riding for Bultaco, asked Thiel to make him a 250 for the 1977 season. By that stage, Nieto’s vast experience and days as a mechanic allowed him to quickly troubleshoot for the team.

Off the track, he campaigned with Sheene and Johnny Cecotto for improved circuit safety and medical facilities.

In 1981, Motocourse said Nieto wanted to win 16 titles (one more than Agostini) and to win in the 250 class.

In 1982 he raced a factory Honda triple in his home GP at Jarama and the following year qualified on the front row for the Austrian 250 GP.

Motocourse editor Peter Clifford wrote of Nieto: “He is the cornerstone of paddock activity. His humour and liveliness have become a vital part of the nomadic life.”

His paddock presence was hard to miss on another score – Nieto had the largest motorhome, only approached by Freddie Spencer’s unit.

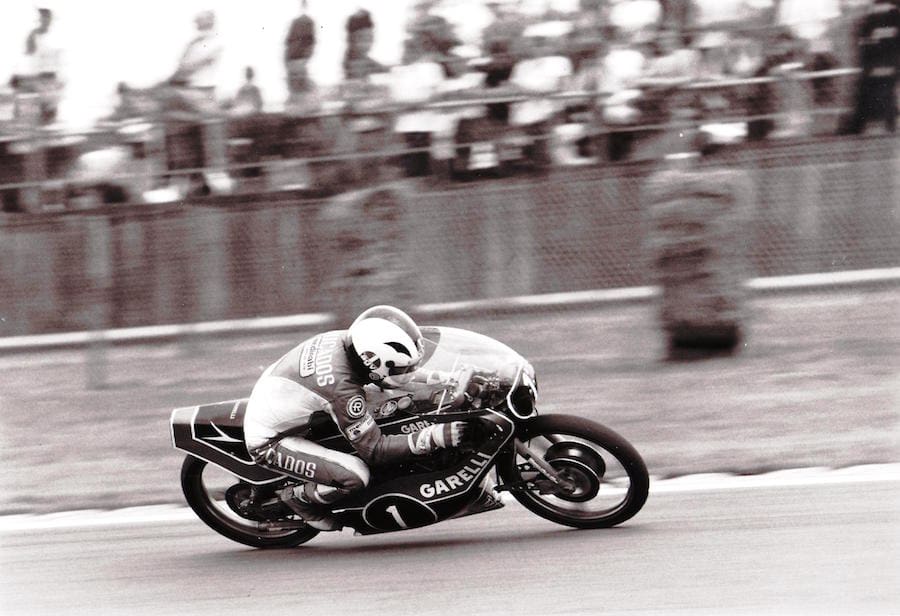

Nieto’s title-winning career stretched from 1969 and the 50cc crown with Derbi, to 1984 and the 125 title on a Garelli. His last GP victory, and his only win in the 80cc class, was at Le Mans on a Derbi in 1985. He retired from racing in 1986, aged 39.

When Valentino Rossi closed on Nieto’s 90 GP tally, Nieto reportedly told him to do it at Le Mans – he would be there.

Nieto claimed world titles on a record five makes – Derbi, Garelli, Bultaco, Minarelli and Van Veen Kreidler.

In world championship racing, only Agostini and Rossi have won more grands prix, and only Agostini has won more titles.

Post-racing, he was a successful team manager and commentator. He ran Emilio Alzamora’s team when he took the 1999 world 125 championship without winning a race. Alzamora went on to be Marc Márquez’s mentor.

Nieto’s sons both raced, as did nephew Fonsi Nieto. At Le Mans in 2002, Fonsi was duelling with that year’s title winner, Marco Melandri, in the 250 GP. A few laps from the chequered flag, a proud uncle told one of his commentary colleagues, “He’s got him in his pocket now!”

Nieto’s work trackside with Spain’s TVE was described as colourful (earthy by some, colloquial by others) and insightful. The commentary team of half a dozen were on open mikes; they could chime in at any time, and it seemed to work. He was also hugely popular on general TV.

Could we see a rider dominate the smallest class today? Times have changed, with a maximum age restriction on Moto3 and myriad regulations aimed at promoting tight and at times crazy racing. Most riders want to move up, for the challenge, prestige and wages.

Angel Nieto’s road to securing a factory ride and becoming the first Spanish world champion was a world apart from the path his young countrymen enjoy today, but he helped forge that path. His stature is immense, in Australian terms Bradmanesque, with a dash of Richie Benaud for his charisma and profile on television. It is some legacy.

Ángel Nieto – Career in brief

1964 Nieto at 17 signs for Derbi and scores points on debut in the Spanish GP in Barcelona

1964-66 Rides in Spain for Derbi on a 50, as well as a Ducati 125

1967 Still riding for Derbi in Spain

1968 Fourth in the world 50 championship with Derbi

1969 World 50 champion, ahead of Aalt Toersen and Barry Smith

1970 World 50 champion, beating Toersen; second in the 125 title to Dieter Braun.

1971 World 125 champion ahead of Barry Sheene; second in the 50 title to Jan de Vries

1972 World 125 champion, still riding for Derbi, with Yamaha’s Kent Andersson and Chas Mortimer equal second;

50 champion on a race-time countback over de Vries

1973 Seventh in the 125 championship on a Morbidelli

1974 Third in the 125 championship on a Derbi

1975 World 50 champion on a Van Veen Kreidler

1976 World 50 champion and second in the 125 championship with Bultaco

1977 World 50 champion and third in the 125s with Bultaco

1978 Second in the 125 championship riding Minarelli and Bultaco; one 50 podium on a Bultaco

1979 World 125 champion, dominating the season on a Minarelli

1980 Third in the 125 championship for Minarelli, four victories

1981 World 125 champion for Minarelli, eight victories

1982-84 World 125 champion for Garelli, six victories each year

1985 Nieto and Garelli tackle the 250 class; Nieto scores 80cc victory at Le Mans on a Derbi, his last GP win

1986 Races Derbi 50 to seventh in the championship and MBA to 13th in the 125 title

Nieto vs Sheene

Barry Sheene’s Spanish connection was well documented. His father, nicknamed ‘Franco’, tuned Bultacos and took the family on holidays to Spain.

Sheene, riding a Suzuki 125 twin – the ex-factory bike of Stuart Graham – was a serious rival for Ángel Nieto. The Suzuki had a six-speed gearbox in place of the original ten-speeder, to suit regulations introduced in 1970.

Nieto and Sheene also competed on 50s in 1971, when the Londoner and Finland’s Jarno Saarinen were drafted into the Van Veen Kreidler squad to help team leader Jan de Vries.

Nieto and Sheene finished one-two in the Spanish 125 GP at Montjuïc Parc in 1970.

Readers of English motorcycle newspapers in 1971 heard a lot of Sheene, especially from doyen reporter Mick Woollett, as he fought for the title. Sheene won three GPs and had a strong finishing record, but Nieto won five, including a dramatic final round at Jarama. That race was a chapter in itself.

Sheene rode the 125 race with a back injury, sustained a week earlier in England, and crashed during the race, breaking a handlebar. He finished third, but it wasn’t enough because Nieto won and took the title.

As Nieto crossed the line, the crowd, reportedly the largest in Spanish motor sport history, went nuts. And this was after a track invasion in the 50 race when Nieto fell off and spectators tried to help him remount!

The race director dropped the chequered flag and joined in the celebrations – with the remainder of the field still racing. Chaos ensued. Some riders backed off and lost places, some slowed and still struck spectators. Second-placed Chas Mortimer was punched in the face while trapped on the ground under his bike!

Australian connection

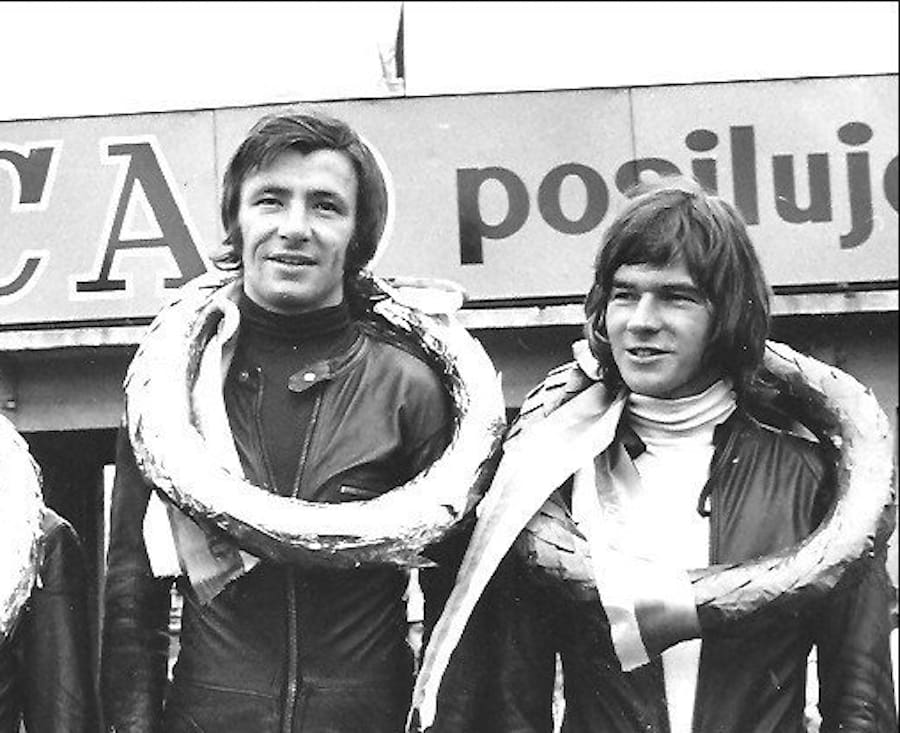

There’s a story Australian international Barry Smith loves recounting. It’s how, in September 1969, the Derbi factory boss paid him the equivalent of 60 per cent of his yearly retainer not to kick emerging star Ángel Nieto off his motorcycle in the final round of the world 50cc championship at Opatija in what was then Yugoslavia.

That such mischief was possible highlights the different times in the 1960s – long circuits, sweeping sections of track with no spectators, and few if any television cameras.

Smith and Nieto were Derbi teammates, vying for the title with two Dutch riders. Both Derbi men had won two GPs that season, but the pride of Spain was at stake. Derbi wanted favoured son Nieto to claim its first title and be the first Spanish world champion.

Nieto did win the crown. Last-lap mechanical failures in the last two races cost Smith his chance.

At the end of 1969, Smith called time on Europe after six years. Derbi wanted to keep him, but he would again be playing second fiddle to Nieto.

The experience didn’t stop Smith shedding a tear when he heard of Nieto’s passing. They were on-track rivals, but mates off the bikes. “Between races, he’d jump in my van and we’d go sightseeing,” Smith said.

“It’s very sad; he was an icon, like Agostini in Italy. It’s amazing that after 13 titles and risking his life for 30 years, it should end in a road accident. In Spain, where motorcycle racing is second only to football in popularity, he’s a huge loss.

“Nieto was second only to Agostini for talent, skill and longevity in that era; a stand-out over the long term. He stayed on bikes, didn’t crash a lot and ended up with so many titles. He was my apprentice as it were when we were first together at Derbi, but he soon learned. A clever guy. Earlier, he’d learned from Derbi’s first factory rider, José Maria Busquets.”

A racer through and through, Nieto did not like losing, especially in his early years. Smith’s recent book Whispering Smith has a podium photo after one loss. The expression ‘a dark look’ doesn’t do it justice.

Smith didn’t just provide a benchmark for Nieto. His trips back and forth from Barcelona to the UK in the late 1960s were vital to the Derbi race effort, as he would beat import bans by bringing in Dunlop tyres and quality steel Reynolds tube to make frames.

“In the Franco era, everything had to be Spanish. The sparkplugs were Spanish Bosch and were crap; the porcelain fell out. The oil was crap and the bikes seized. Once Derbi started to go to the GPs regularly, the team could source better products.”

Smith says part of Nieto’s schooling was how to ‘nurse’ the bikes. “They kept telling him to treat the bikes gently. At Assen and Spa when I won in 1969 he broke down. At Imola, we were one-two, well in front and racing for the individual win, and we both had mechanical problems. They gave us both a bollocking for that, because of course they wanted to win the manufacturers’ title.

“Nieto was a fussy eater,” Smith recalls, “so he didn’t like going outside Spain. He hated English food. In terms of drink, I never saw him touch anything stronger than sparkling water.”

WORDS DON COX & Alan Cathcart

PHOTOGRAPHY JOAN SEGURA ROVIRALTA, BIKER EDICIONES & ALAN CATHCART