The appealing thing about old bikes is that they look cool, stir memories of lustfully wanting what you couldn’t have, or that you did own and wish you still did. These are all very human feelings and fair enough.

The realities of a mid-’70s, spaghetti-framed sportster, though, are the realisation that motorcycle development has continued at such a rate since then that you wonder what all the fuss was about when you jump on board. Well, I do anyway. I like old cars and new bikes – that’s just the way I roll.

I like my bikes new because they are more likely to stay underneath you and with things where you left them, rather than something falling off or breaking or just not riding like you want them to. Old bikes can be cool, but I just prefer shiny new ones. Which is perhaps why I like Kawasaki’s Z900RS so much.

The retro thing isn’t new: Triumph has a range of well put together nods to yesteryear, and it works great for them. Yamaha’s XSR900 is one of my favourite bikes (there seems to be a theme developing here) and Ducati’s Scrambler also fits the mould. So Kawasaki’s Z900RS isn’t a unique take on another niche of motorcycle, but it is one that arouses so much in so many.

Kawasaki’s 1972 Z1 in all its brown-and-orange Jaffa glory stirs so many in the loins these days, because it was tough, horn-looking and it pioneered ‘fast’. It just fitted the ’70s lifestyle so well. And today the new RS version does exactly the same thing.

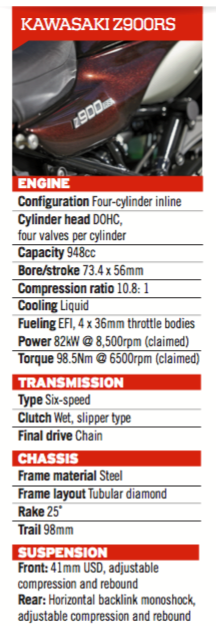

First of all, that engine is as close to a perfect roadbike engine as you get. Kawasaki purposely set out to re-tune the Z900 donor engine for more bottom end and mid-range torque, a move that often spells doom for a once lively and exciting engine. Because the engineers got the revised cam profiles and heavier flywheel right, however, the end result it a torque monster that has you wondering if the claimed 900 displacement is right – surely it’s a 1000?

Also, because it’s an in-line four in a category resplendent with triples and twins, the fact its incredibly user-friendly nature is matched to a serious amount of grunt when you ask for it makes this a formidable engine.

Some international reviewers I spoke to after the bike was launched overseas, before it arrived here, claimed the throttle response was a shocker – like the snatchy nature of the first Yamaha MT-09s at launch time. The one advantage of Australia often being the last in line for new machinery is that when it gets to us a lot of the bugs are ironed out, and this is the case here.

Throttle response is superb, the loud-tube hooked up to the rear wheel in a way that makes the traction control all but redundant (see sidebar). I find myself rolling the bike in and out of gaps and road lines with utter faith that I’m only going to get what I ask for, nothing more or less. And it all sounds magnificent.

Kawasaki claims the Z900RS’s exhaust system was put together with “careful consideration”. Whatever they did, it worked. This is the kind of bike that brings the in-line four back from the humdrum. It has never really left, but its incredible flexibility, with fewer of the downsides it used to be burdened with (such as weight and bulk) mean it is likely to have something of a renaissance in this kind of bike.

This engine is close to flawless.

Happily, it’s bolted into a chassis that can handle the awesomeness too, something you can’t be sure of when a manufacturer slings the word retro at something. Based again on the Z900 chassis, the frame needed some finessing to fit that magnificent tank and the bike has had the front raised and rear lowered for a more upright ride position and a less aggressive stance.

Aside from that, the bike feels very Z900-like when it comes to stability and nimbleness. Whether it’s an inner-city roundabout or a scratching road’s sweeper, the Z900RS settles into it with solidity and just aching to have the loud-tube twisted to get to the next one.

Sure, twin rear shocks would have made the bike look more ’70s, but this isn’t a replica. It’s a modern take on an old bike and twin shocks simply wouldn’t have done as good a job as the modern-spec monoshock.

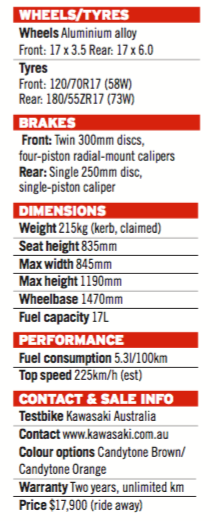

The bumps and general shittiness of the many backroads I rode were gobbled up by the Z900RS. It stays straight when it hits the road zits, and the compromise between compliance and firmness is good, even when leaning towards the soft side.

I really like the steering too, just like I do on the Z900, and this blend of neutral steering and predictable handling gives you confidence – well-placed confidence – meaning the bike is fast. Probably faster than it should be given that the design brief mentions rider-friendliness a lot. It is rider friendly, but it can be hustled along hard as well. Just like a big Kawasaki should be.

It’s not breathless at the top of the 10,000-redlined tacho either. It still pulls, but the ideal rev range is between 3000 and 8000rpm; keep it grunting in this range and the tyres will melt and your riding mates will struggle to maintain station.

I was happy to do this for tankful after tankful, not just because the bike is comfortable but also the way it rides. It just doesn’t tax you like some bikes do, either in anxious anticipation of it doing something unexpected or in the effort required to shuffle it along at a solid road pace. Steering,throttle and brakes are all light and precise enough to minimise effort. You can be lazy-ish on this bike and it will still perform.

Keeping track of those revs is a cool thing to do, thanks to the mostly retro clocks. I loved the old-school needle-and-dial arrangement. This style works because once you are used to a needle’s position at certain speeds and/or revs, you don’t need to actually read the speed/revs, you can use your peripheral vision to take note of the info you need. In these days of wildly varying speed limits and red-light cameras, being able to keep your eyes up is a winner, and the antiquated clock arrangement is a good way to do it.

Nestled in between those bullet-shaped clocks is a modern component, an LCD screen that looks slightly out of place but has all the modern info, including a fuel gauge (which was out of sync with the range predictor on our test bike), temperature gauge and traction control status.

Importantly, there is also a large gear indicator front and centre, something smooth, torquey bikes need lest you sit in fifth the whole way up the freeway, only realising when you shift down for the first set of lights. If you are used to shifting gears by how vibey the bike has become, you will be in trouble on this bike – it’s smooth as.

Another obviously modern touch is the headlight treatment. It’s the right retro shape, but if you rode with a light like that back in ’72 you would have been burned as a witch. The six-chamber LED lens splits duties across four chambers for low beam, the remainder for high. The end result once you have adjusted it down, as it’s a Koala killer in standard form, is it lights up the road well at night.

The tail light is also LED, but it’s the retro tailpiece that takes your eye. It’s one of my favourite bits of the bike, particularly when paired with the paint.

The paint looks deeper than your swimming pool’s deep end in the sun, certainly a sizeable quality leap above the acrylic-spec paint from the ’70s. The tank’s graphics are applied immersion style, meaning the Jaffa paint isn’t raised above the base coat’s layer, another detail touch that adds to this thing’s appeal and high build quality. With no knee indents and the flowy shape suiting the flowy graphics, it’s a worthy centrepiece.

The tank also offers a lengthy touring range of around 350 kilometres, which that seat will happily let you sit there for. It’s as comfortable as it looks, made from different materials to give it a two-tone look, and is one of the retro bits that work better than many modern seats.

There has been some haughty discussion surrounding the price of this bike, with some observers complaining that $17,900 (rideaway) is a bit rich. But when you look at the detail that has gone into this bike, such as the immersion graphics on the tank – not a high-production volume-friendly exercise – it starts to make sense.

Personally I think the price tag is on the money (remember, it’s a rideaway price). Yes, a Yamaha XSR900 is much cheaper ($13K plus on-road costs), but it’s a triple, and doesn’t have the build quality or heritage. I love the XSR, so would I pay overs for the Kawasaki? Yep. It’s a great ride; it makes me want to get on and never get off. It doesn’t overwhelm the XSR’s feature set, but it does add up to more bike in comfort, performance and (in my opinion) looks.

If you are an age where a Z1 was your object of desire, then this bike will satisfy. It is good enough to have riders returning to the licenced fold after years of just thinking about it.

Kawasaki has blended retro with modern exactly right with this machine. I can’t fault how it rides, within its design brief, and even factors such as ground clearance are better than I expected. The engine is superb, the chassis is so easy to use an L-plater could get it safely around the block, and the bike sounds and looks like something from your ’70s-spec dreams.

If you’re after a replica, you won’t be happy. If you want a bike that reminds you of yesteryear yet inspires new feelings of the motorcycle variety, this is your beast. It’s my favourite bike of 2018 so far, just like the Z900 was for last year, and it will take a special bike to top it.

Get a ride on one soon. Just have your credit arranged first. You’ll need it.

TEST SAM MACLACHLAN PHOTOGRAPHY JOSH EVANS