It’s not as though the Goldwing is a new concept, but to those of us who only get to ride them occasionally there seems to be a point, about an hour or so into a trip, that you have to laugh out loud at the sheer audacity of these monster tourers. In some ways they seem to defy physics.

There you are, allegedly exposed to the elements, but belting along in complete comfort, on a bike that looks like it may need assistance to make it through a corner but handles just fine, thanks. Yep, it can seem a little weird. A (large) mass of contradictions.

Now the thing is, weirdness aside, the Goldwing has long been one of the planet’s signature heavyweight tourers. In its prime market, the USA, any shift in the model’s design is seen as significant and bound to put pressure on others – mainly Harley’s upper-echelon Electra Glide offerings – to keep up.

It’s no exaggeration that this latest ’Wing is good reason for its competitors (which includes BMW’s straight six K1600 series) to sit up and take notice. Honda clearly has no intention of giving ground in this market.

While the 1800cc Goldwing platform has been given a make-over or two since launching in 2001, this is the first major revision and is a new motorcycle. Sure the overall architecture looks similar, but it’s definitely not the same thing. And in most respects, it’s better.

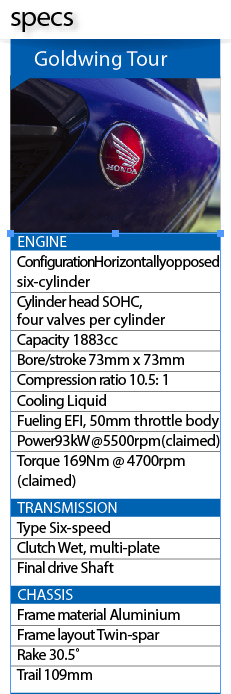

To give you an idea of how complete the redesign has been, the engine, transmissions (yes, there are now two options), bodywork and electronics are all different. The really radical change, though, has to be the chassis. It has ditched a conventional fork in favour of a wishbone set-up with a passing resemblance to BMW’s Duolever front end.

Really, it’s the new chassis which has realised the most dramatic shift in the character of the ’Wing. If you’ve ridden examples of the previous generation, you might recall them being impressively fast and, for their day, reasonably tidy units through a set of curves. However late-model luxo yachts – from BMW in particular – significantly lifted the handling standards for the class, and Honda has responded.

Literally within seconds of getting rolling, the difference between the old and new generations is abundantly clear. It’s as if someone has physically shrunk the motorcycle and given it handling lessons. Seriously. So what are we dealing with?

Honda has again gone for a twin-spar aluminium frame, but this one has been redesigned with a new and more compact engine in mind. The engine is said to be located 40mm further forward (a lot) and the rider just shy of that at 36mm.

As for the wishbone front-end, it to a large extent separates suspension and steering forces. Just as significantly from a ‘feel’ point of view, the suspension claims 30 per cent less stiction and the side-to-side handlebar turn a massive 40 per cent. Honda also claims: “In addition, a patented steering cross tie-rod connects the handlebars to the front axle and the position of the handlebar pivot with less mass around it (plus siting of the handlebars) delivers an entirely natural feel to the rider.” Natural feel? Yep, that’s a pretty good way to describe it.

Out back, the swingarm has been lightened for a total claimed weight saving of two kilos on that and the frame. All up, Honda claims the Goldwing has lost a massive 34 kilos, though there will be some variation on that, depending on which of three models you’re talking about: the Goldwing, the Goldwing Tour and the Tour Premium (see sidebar).

As for suspension, electronics have entered the fray with a nice and simple dial-a-ride option. Select one or two riders, with or without luggage for your rear ride height/preload. Damping front and rear is also adjusted with electronics, linked to four riding modes: Tour, Sport, Econ and Rain. Tour and Econ use the default damping and brake response settings, Rain softens the suspension, while Sport goes the other way and gives a sharper damping response and a firmer feel on the rear brake lever.

As for braking, a latter-day version of the combined braking system (aka CBS) is in play, with what seems to have become the traditional three-piston calipers in place. We’ve seen variations on this going back decades, across a number of models, including the Blackbird. That lot is, of course, tied to ABS.

And the engine? The familiar flat-six configuration is still there, though the changes are extensive, pulling significantly more performance out of pretty much the same engine capacity, which is up all of one cc! Honda has changed the bore and stroke dimensions to completely square at 73mm (previously they were a little oversquare), raised the compression, revised the fuel injection and induction, and is now running four valves per cylinder off the single overhead cams. Oh, and of course it’s running fly-by-wire.

Even the ancillaries have come in for attention. For example, the starter and generator are now the same unit – very sensible.

As for the transmission, you get a choice of two: a six-speed manual with quickshifter in both directions, or a seven-speed dual-clutch auto (DCT). Traction control comes with the package, regardless of which shifter you end up with. The manual retains the old system of using the starter motor as a reverse, while the DCT has a crawler mode for manoeuvring forward and back. Our test bike was the Tour version, which means we scored the manual.

When it comes to creature comforts and rider aids, there’s a fair bit to get your head around. This really is one of those motorcycles where you might have to break with tradition and actually read the instructions.

Naturally you have screens for the assorted riding modes and suspension loadings, which are self-explanatory. In addition, you’re running heaters for the handlebars and both seats, plus an entertainment/navigation system. Let’s not forget the tyre-pressure monitoring system, hill start assist on the DCT models, cruise control, and even an auto idle stop if you want it. There’s plenty to get your head around.

The entertainment section is a big departure from previous practice, as it depends on you installing Apple Carplay, which means you’ll need a reasonably late-model Apple device to ‘talk’ with it. Given the motorcycle costs north of $40k, that’s not a huge financial imposition – if you don’t already have one. Once it’s all up and running, it opens up a whole world of options, including running web-based music services and satnav through the display on the bike.

There is no question the thing is big, but it’s substantially different to and lighter than the first-gen 1800. It has similar physical presence and is, in fact, 5mm longer in the wheelbase.

However the combination of a quite different ride position and a radically-changed front end conspire to provide a very different feel behind the handlebars. Add in the substantially lower weight and you have less reason than ever to be spooked by the size of the monster.

It’s no flighty commuter, but you can tackle heavy traffic with more confidence than before, with a far more responsive tiller at low speeds. Power delivery in Tour mode is entirely predictable for tight manoeuvring, while the fact the brakes are linked is pretty unobtrusive.

However that’s not what a ’Wing is about, right? What we should be looking for is the wide open spaces. To that end when you go to load up, a couple of things strike home: both the fuel and luggage capacity have ben reduced. In the case of fuel it’s gone from 25 to 21 litres – not a complete tragedy as, on cruise at legal speeds, it will get 5-6L/100km.

As for the luggage, it’s most noticeable with the topbox. It will still take a couple of helmets, but not two super-sized Shoei shells. Pannier space seems to have dropped back a little, too. In saying that, it’s easy enough to pack accordingly.

Once you’re loaded and rolling, the easy-going nature of the bike is quickly apparent. It’s still ultra-stable, but is now a lot easier to redirect round an obstacle, or to slice through a set of turns.

When it came to the assorted riding modes, our default position was Tour. It provides plenty of performance and response, while being perfectly manageable. Sport is interesting, and definitely provides a sharper throttle response, along with firmer suspension, but it’s harder to keep the ride ultra-smooth and is not particularly pillion-friendly. Good fun solo, though.

The dial-a-ride style suspension set-up does really work and the simplicity is great. Over the time we had the bike, it simply didn’t get caught out. Sure a really big mid-turn bump would wake you up, but there is no wallowing or head shake. It will never be mistaken for a sportsbike, but it’s capable of good point-to-point times without putting you in fear of your life.

The manual transmission with power shifter is a gem. It works just fine if used conventionally, however your pillion will thank your for using the electric assist. It’s ultra smooth and makes for a far more pleasant life on the rear throne.

Braking on the much-updated braking system is strong and predictable, with decent lever feel. Really, it just gets on with the job.

Here’s the big news for taller riders: the electrically-adjustable windscreen provides better coverage than ever before. At 189cm, I was getting a hint of spill over the top at max extension, but it really was good. A nice touch is the pop-up air blade at the base, which can direct some cooling air in behind the screen on a hot day.

Anyone who does big miles (why else would you have one?) will become best friends with the cruise control. It’s accurate and smooth, with the dual benefits of taking the load off your right wrist and delivering better fuel economy.

Any Goldwing built since 2001 has been a proven serious mile-eater. Their greatest virtue has been their ability to take you several hundred kilometres, pretty much regardless of the weather, and land you at the other end far fresher than you have any right to be. So far as I can tell with the new model, that hasn’t changed.

What has is the dynamics. Really, the previous model was good for its day but has since been overtaken by rivals. This model restores the balance and is a very capable device. The catch? Well, you need to be cashed up to afford one, as we’re talking on-road prices of high thirties to mid forties. A lot of money, though it is a hell of a lot of motorcycle…

Words Guy Allen Photography Ben Galli & GA