Life has a habit of funnelling me into a rut. Perhaps you’re the same. If you’re fortunate, like me, it’s a comfortable, predominantly enjoyable rut, but it’s a rut nonetheless. Same places, same faces, same meal choices, routines, experiences and results. The same petty annoyances and minor regrets. It’s nothing to be ashamed of. If you’re reading AMCN, rather than using it as insulation because you’re sleeping rough, I’m assuming you’ve reached a level of comfort too, and life isn’t a competition – unless you’re a shallow go-getter with self-worth issues. Our existences are not life and death. Just life.

My personal rut isn’t without complications, but if I were offered it, as a 16-year-old, leaving school with a below average, free education, I would have taken it without a blink, even if the thought of two children would have come as a shock to the teenage me.

A big part of slotting into the groove and following it, like a stylus follows a vinyl LP’s spiral scratch, is because it’s easier to say no to new ideas than yes. Snow Quake was the result of a lot of people, from all over Europe and beyond, ignoring what was easy and saying yes.

The idea was first mooted in May 2015, as a throwaway comment between myself and Alessandro Rossi, one of the owners of Milan’s Deus Ex Machina multi-faceted store, the Portal of Possibilities – the Italian outpost of the Australian motorcycle lifestyle brand. Rossi suggested we work on an Italian version of Dirt Quake, a motorcycle dirt track race event I organise in the UK and USA (see AMCN Vol 64 No 4). To try and avoid the rut, I replied, what about Snow Quake? That’s all it took for the wheels to be put in motion.

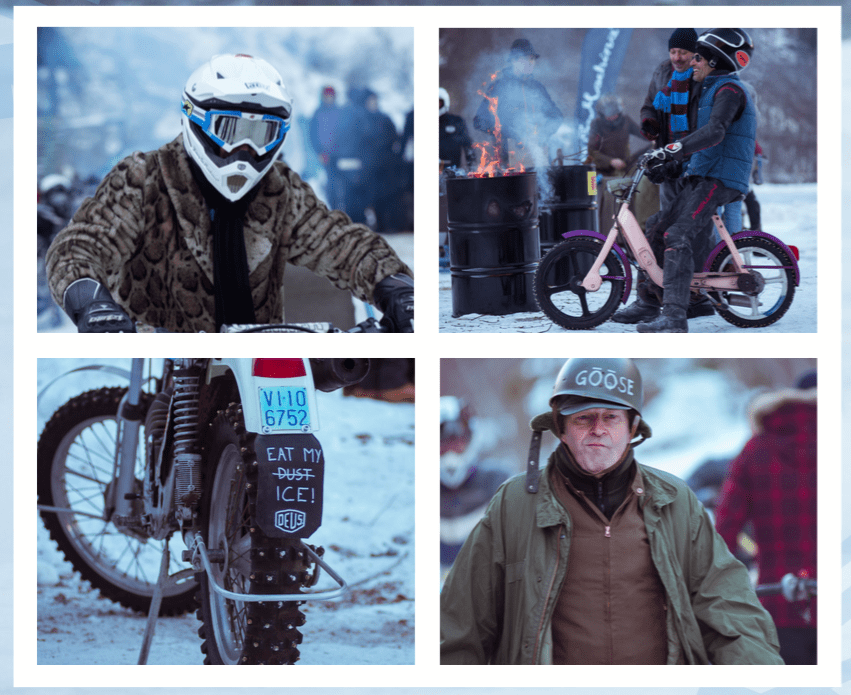

Eight months later a group of seven different nationalities pull into a shadowy valley off the SS299, under the impassive gaze of Monte Rosa, the second tallest mountain in Europe’s dominant mountain range. It’s eight degrees below zero and won’t get any warmer all day. Oddball motorcycles are unloaded from panel vans and pick-ups. Some are racebikes, others are roadbikes. Some are very new, others are 70 years old. All have studded tyres to allow them to gain traction on sheet ice.

The Ice Rosa Ring, in Alagna Valsesia, is a purpose-built ice racetrack, with arcing left and rights and changes of elevation. Of the 30 invited racers, perhaps five have experienced riding on ice before. No one in attendance has organised an ice race before and it’s made clear to all in attendance that this is an experiment. I’m in charge. I’m wearing a stupid hat and I’ve jumped the tracks. I’m in virgin territory now. Off-piste. Be patient while I work out what should happen next.

Motorsport is normally highly regimented, with governing bodies and whole books of rules and regulations. These are important, for two reasons: motorsport is dangerous, but as one participant previously explained to me, If it can’t kill me I’m not interested in doing it. Secondly, some people really, really want to win. This is the most important thing in their personal rut – triumphing over strangers.

Snow Quake could guarantee the danger. The tyres these bikes were fitted with were like circular saws. They cut and gouged hands and arms just trying to fit them to a motorcycle. Imagine what they’d be like at 100km/h. When it came to the other normally crucial element of motorsport, the winning, I made it clear than no one really cares. The riders seemed to get it and practice started. Two hours late.

The weather was so cold it was killing highly strung bikes. Engine oil had turned to the consistency of tar, batteries were as brittle as breadsticks.

Eventually we were on track. The specialist tyres I’d been sold by a so-called friend had all the grip of wet soap and I crashed three times, before deciding that I couldn’t continue. Another British rider’s bike, with good tyres, but bad electrics, wouldn’t start, so we made one good bike out of two under-performing ones and were both able to race.

Two old friends offered different ends of the spectrum. One was Nick Ashley, the creative director of British luxury clothing brand Private White VC. He was wearing woollen plus-twos and riding a World War II-era Harley Davidson 750. At the other end was former World Superbike, World Supermoto and current World Endurance racer, Giovanni Bussei. The Torino rider was in trademark white Alpinestar leathers with gold fringes flying from the arm seams.

The hero of the event, as far as I was concerned, was Marco Belli, an amateur dirt track racer from Varese, who has driven the equivalent of to the moon as back to compete in dirt track races in Europe and beyond, and always for nothing more than fun and a plastic trophy. As one of the co-organisers and friend of Deus Ex Machina, Belli was coerced to race a heavyweight Yamaha XJR1300 with clip-ons bars, shod with Pirelli spiked tyres that looked like they were created by Marilyn Manson’s wardrobe designer. With the casual air of a man who wrestles salt water crocodiles for a living, Marco grabbed the heavyweight four-cylinder bike by the scruff of its fat neck and rode like his life depended on it. I was in a race with him, me on a dirt track-spec Rotax 600, and was leading until he came past with a menacing howl, a cloud of ice chips partly obscuring his progress.

The relaxed nature of the event stretched to the lap scoring. Normally a small team with clipboards, or better still, laptops and electronic transponders, log who crosses the finish line in relation to the other racers. It’s important, remember? We didn’t have anyone who could help. Instead, we had a white board and some pens. When a rider won a race they marked it on the board. The same for second and third. They were hardly going to lie in front of their friends and peers. Beyond that, no one cared.

Giovanni Bussei, a man who has raced all over world as a salaried professional (albeit an eccentric and individual one), reckoned Snow Quake was, “A truly romantic race, with a truly romantic spirit.”

After hours of practice and 11 separate races, it was time for the final. I’m not going to contradict myself and tell you who won, because it didn’t matter. The only thing that really mattered was that people said Yes, to a silly idea. And that no one died.

Words and photography Gary Inman