Yamaha have undertaken their biggest engineering leap in decades, while Ducati needs to avoid another misstep

The 2025 MotoGP season was a study in contrasts, triumphs and maddening headaches. A year that reminded us just how brutally honest this sport can be. Ducati, the undeniable juggernaut, collected an eye-watering 17 GP wins and a world title for Marc Marquez, yet behind the glittering numbers lurked chaos. While the GP25 could be sublime in the hands of the ‘alien’, it left Pecco Bagnaia and Fabio Di Giannantonio wrestling with a bike that seemed to have a mind of its own. Meanwhile, brother Alex, on what was essentially last year’s GP24, waltzed to second in the championship, a sharp reminder that, sometimes, evolution can outpace understanding.

KTM, on the other hand, spent 2025 as the bridesmaid without a single win. Pedro Acosta and Maverick Vinales flirted with victory and tasted podiums, sure, but first-place glory proved elusive. Development struggles, an understeering RC16 that chewed up tyres, and financial constraints had the Austrian squad scratching its heads early on. But perseverance paid off: clever chassis tweaks, mass dampers borrowed from F1, and positional adjustments on the bike turned mediocrity into consistency. The RC16 may still crave grip and corner longevity, but KTM showed that ingenuity and a little lateral thinking can keep a team competitive.

Aprilia emerged as the steady achiever, its RS-GP carving out four wins and a flurry of podiums. Marco Bezzecchi seized the role of No.1 rider with maturity, guiding development and squeezing stability out of a nimble, aerodynamically clever package. From leg wings to weight balance adjustments, Aprilia’s engineers clearly understood the subtleties of tyre management and aerodynamic glue; an impressive feat that turned the RS-GP into the grid’s most consistently competitive performer behind the outright leaders.

Honda’s RC213V showed flashes of brilliance and hinted at a resurgence. The lone win and a spate of high-speed performances came courtesy of careful trail-braking work, chassis ingenuity and new tech leadership from Romano Albesiano. They may still be chasing cornering stability and lighter swingarms, but Honda’s techs reminded everyone that under the right guidance, even a struggling V4 can punch well above its weight.

Yamaha, meanwhile, trudged through the swansong of their inline four M1, chasing speed and trying to stay relevant. Fabio Quartararo carried the flag at times, but the limitations of the ageing design were stark. Behind the scenes, though, a V4 revolution was quietly underway – a painstaking, measured approach that suggests 2026 could be a very different story…

YAMAHA – Zero GP wins

Yamaha’s engineers worked their arses off in 2025. They were kept busy squeezing out the last bit of performance from an outdated inline four package, while at the same time working hard on the new V4 for 2026. Having to work double shifts is the price they had to pay for waiting this long to enter the ‘V4 engines only’ MotoGP party.

The swansong of an inline four

The M1 that Yamaha rolled out at the first test was an evolution of the 2024 bike, not the revolution some were hoping for. But at least the rear ride height activation happened automatically now, thus making sure it drops at the right moment on corner exit.

While the inline four M1 might be an outdated design, it could still be fast – very fast at times. But only in qualifying and most of the times only in the hands of ‘alien’ Fabio Quartararo. However, even starting from pole position was not enough to prevent him being overtaken by faster bikes on the straights, which then went on to block his line through the corners.

In desperate need of speed, various engine updates were tried and discarded, until Yamaha finally brought one that not only delivered extra ponies but in a user-friendly way. Having finally found more top speed, Quartararo then switched to an aero update with more drag. This made him lose some of this newfound top speed but it increased his corner speed, effectively improving his lap times.

At this point, Yamaha stopped developing the inline four and it was all hands on deck for what is their biggest racing adventure in years, the all new V4 powered M1.

The birth of a V4

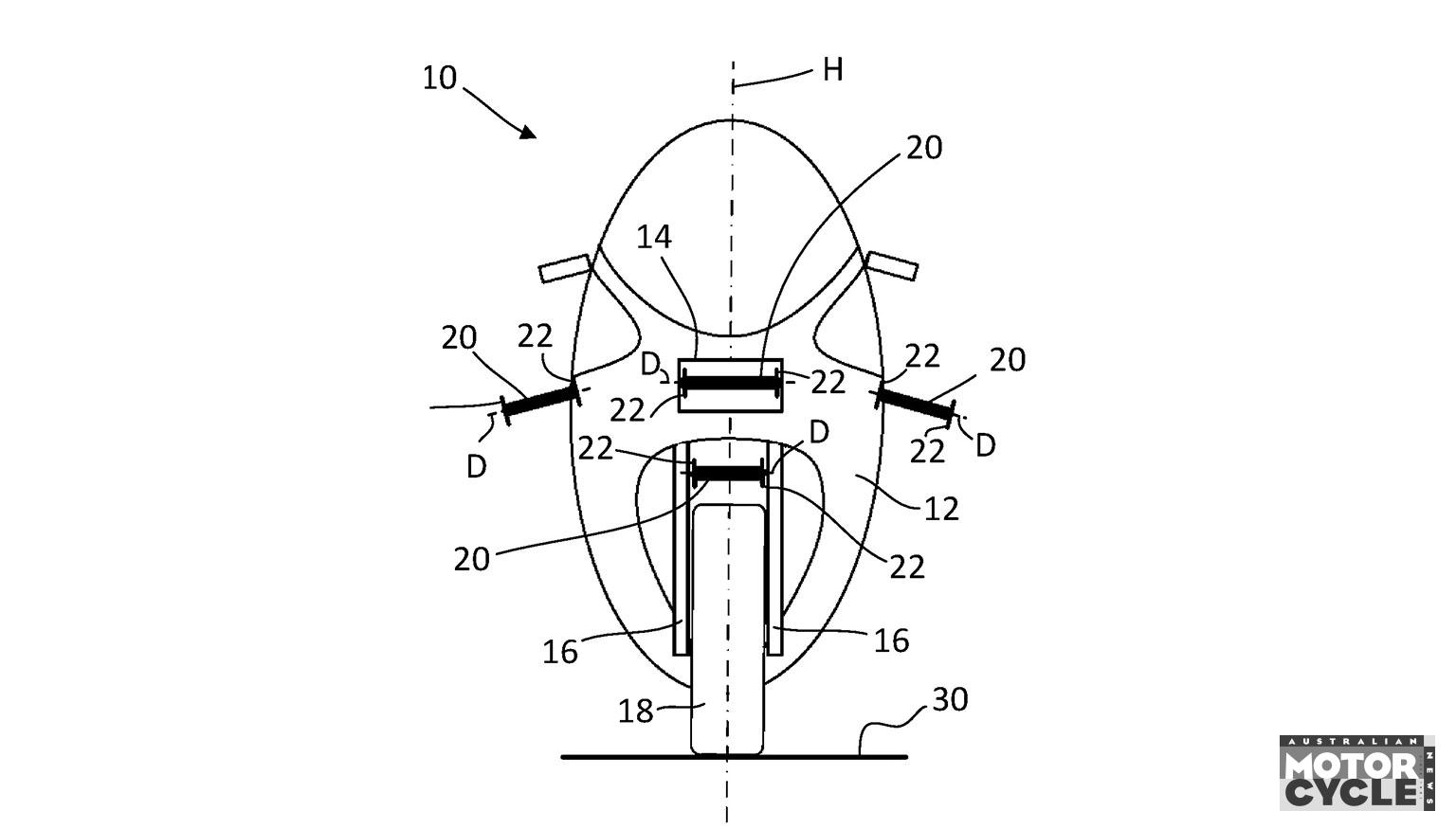

Thanks to the very different layout of a V4 engine, more weight will automatically be shifted towards the rear of the bike and more aero parts can be fitted inside the allowed maximum bike width. Yamaha could use very little of their inline four-based experience; a total redesign was needed and that’s where I expect to see ex-Ducati technical director Max Bartolini making the difference. So far, his approach has been one of carefully allowing the completely new V4 to walk before expecting it to run. The engine is not yet delivering the power that’s needed and the aero package was copied from the inline four bike – thus avoiding confusing feedback by at least staying with the same aero influence.

At the Valencia test, the bike didn’t make a huge impression. But it wasn’t slow either. After all, this test was not about the ultimate performance, but to gather feedback from all four riders. What we learned most of all is that their V4 project needs more horsepower, and lots of it. They are too far on the wrong side of the 300+hp the class-leading Ducati is rumoured to have. Horsepower comes if an engine has an effective breathing system, can run a high rpm and has little mechanical and thermal losses. Easier said than done but here is what I think Yamaha is working on right now.

Yamaha’s V4 will very likely have its cylinder banks angled at 90° as this layout offers a perfect primary balance, which reduces vibrations and with that, offers a good mechanical efficiency. The resulting size and shape of such an engine makes it also a nice balance between weight, shape and efficiency. Bore and stroke will remain as with the I4. The rulebook limits the cylinder bore to a conservative 81mm to try and keep the cost of these otherwise super high-revving engines under control.

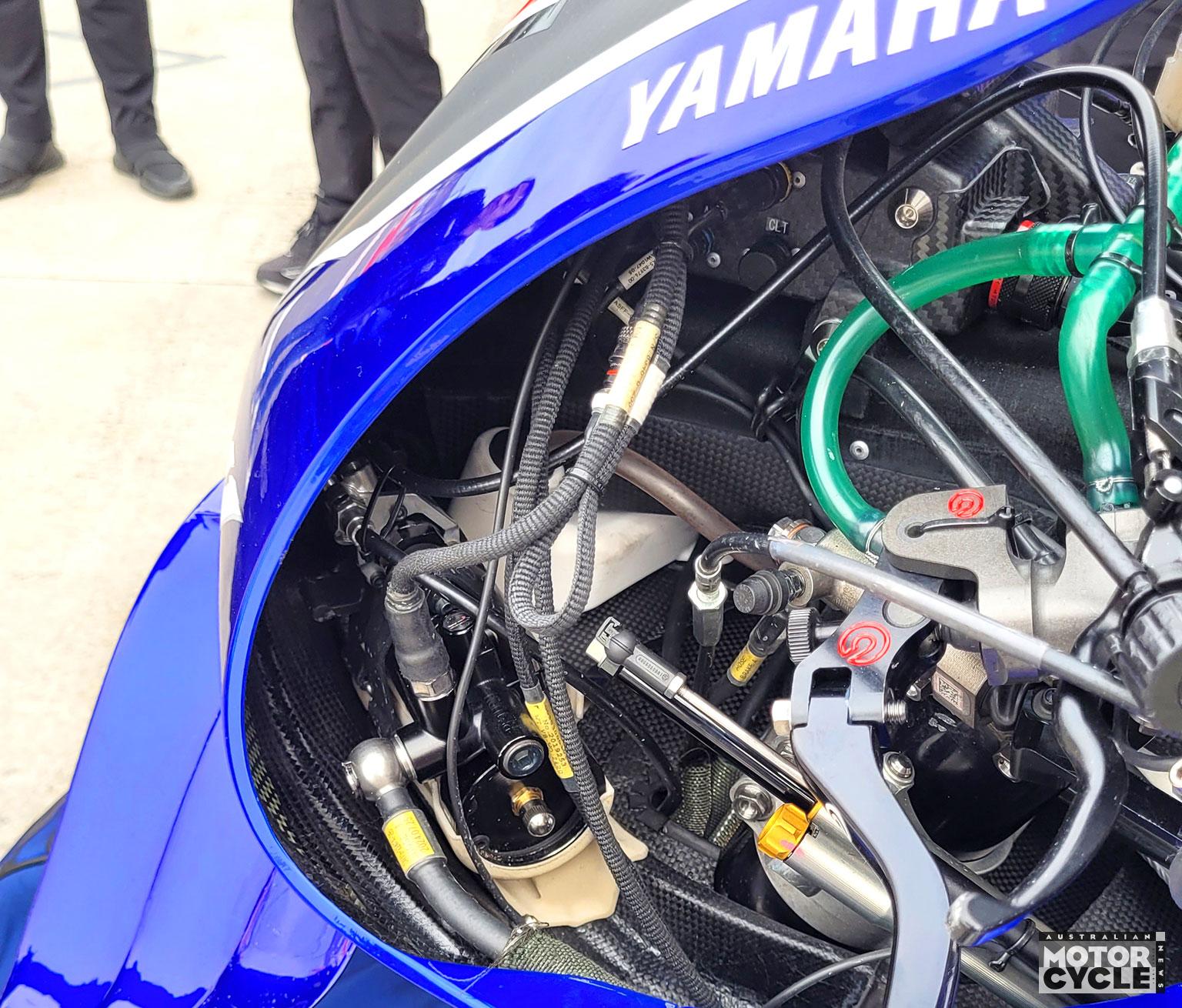

Then they must get their heads around the very different ways the air travels through a V4. At an estimated 150 litre/sec, a lot of air gets pumped through a MotoGP engine. Opening and closing of the inlet valves makes for pressure waves travelling back and forth between the valves and the airbox entrance in front of the fairing. Airbox design is aimed at using these pulses to push more air past the inlet valves. The inlet trumpets will have a variable length, decided upon by a strategy written in the ECU, depending on rpm, throttle position and engine load.

Same goes for the other side of the cylinder heads, where the exhaust routing too is vastly different. Both cylinder banks having their own sets of pipes means that both end up on different positions on the bike. So Yamaha have to pick up on their knowledge of combining these pulses on both the airbox and exhaust side now they have changed to a V4. And to get there quickly, their engine dynos will run overtime, testing reliability while at the same time trying to find the perfect airbox and exhaust design.

And there is the matter of aerodynamics. Having finally a narrow V4 engine means that, within the maximum allowed bike width, more area is available for aero-related designs. What we saw in Valencia was still based on the I4 bike but they must be working hard on this, right on. They will be running simulations with CFD (computational fluid dynamics) software, after which the 3D printers will produce new fairing parts. Then it’s off to the wind tunnel to check the numbers and see if there are no hidden downsides, followed by a first track test with the Japanese test riders. If all still seems pretty good, the package will be given to the test team to see if it also gets their blessing. By that time, it will be the last week of January when we are at the first test of the season in Sepang.

But because calculations can be wrong and test riders in Japan don’t lap at the intense pace of the factory boys, testing with the factory riders is still the key for progress. And that is where Dorna’s concession system comes in handy for Yamaha.

They are listed ‘D’ (lowest), which means they are allowed to do more in order to close the gap (although this only helps if they work for it). Have they got their first aero package horribly wrong? No stress because they are allowed to bring in two more updates, where all others can bring just one. Same goes for the engine, where they can use up to 10 instead of eight engines over the season and – more importantly – can bring as many engine updates as they need. They are also allowed to test at any track they prefer and do so with their factory riders. Plus they also can test more laps, having more tyres available to them.

DUCATI – 17 GP wins

Ducati’s 2025 bike brought them the world title in the hands of Marc Marquez, but also headache and confusion. How could both Pecco Bagnaia and Fabio Di Giannantonio suddenly struggle so much, while Alex Marquez, on Bagnaia’s 2024 bike, cruised to second in the championship?

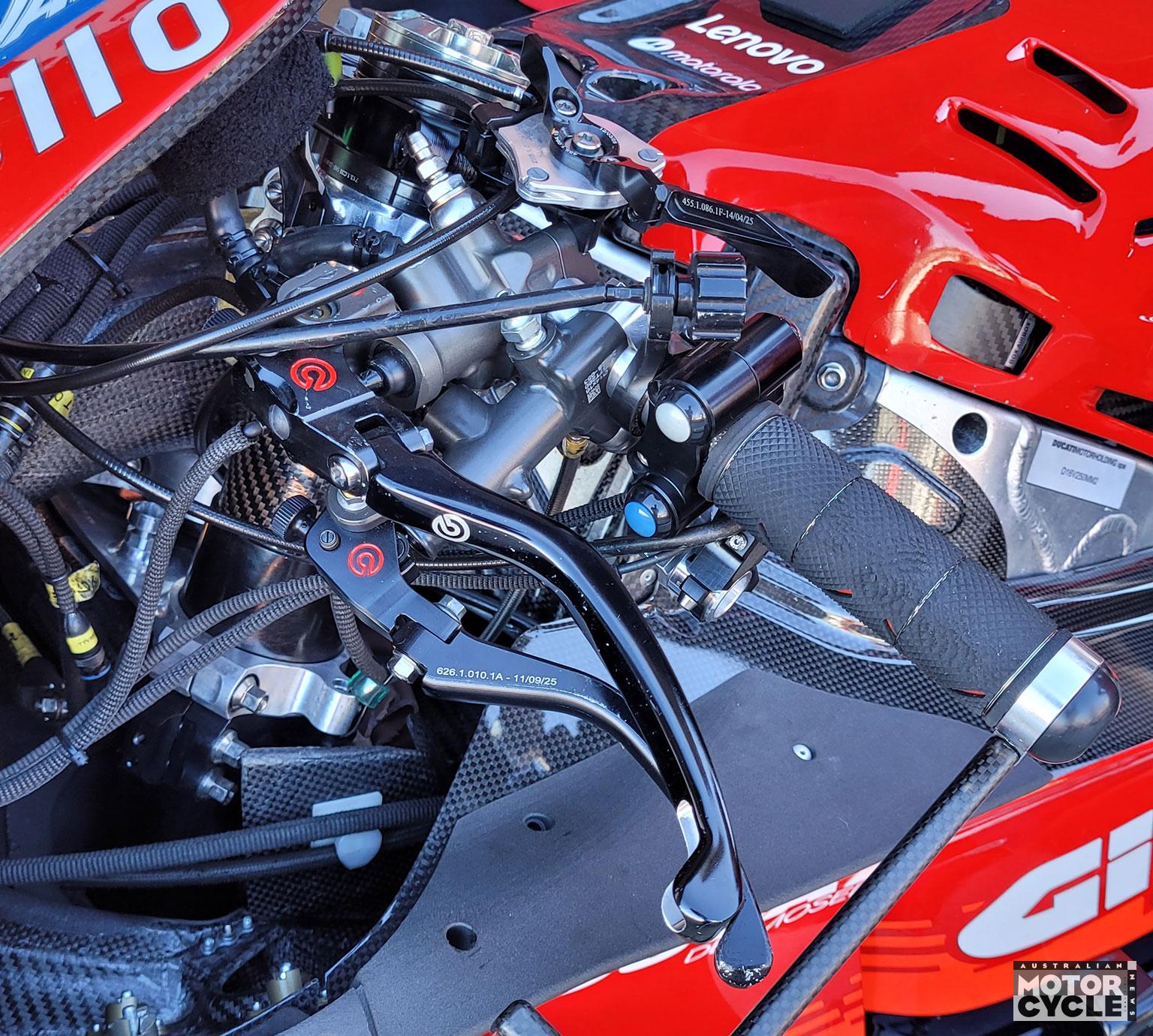

The GP25 that they started with in the test in Sepang featured lots of changes. Compared to the successful GP24, there was a new chassis with another version of the ride height system, a stronger engine and various new aero parts.

Although the extra horsepower was welcome (not that Ducati needed it) something was clearly wrong; the GP25 was now much harder to control during braking – something all three factory riders quickly noticed.

For effective and stable deep braking into the corner, it is vital to control the (negative) rear wheelspin coming from the engine brake control. Too much negative slip and the rear wheel loses grip and becomes unstable; too little and the rear wheel wants to keep pushing, making the bike go wide on corner entry. There is only a narrow window in which things run smoothly – and while downshifting, this slip level can vary quickly between too much and not enough if it is not controlled well. This control depends partly on the EB settings from the ECU but for a large part also on the combined result of the engine’s inertia (crankshaft and flywheel mass) and the compression ratio.

For the ‘alien’ Marc Marquez, the GP25 was more than good enough but the season proved much more challenging and surprisingly difficult for the other two factory riders on the GP25, Bagnaia and Di Giannantonio. This allowed Alex Marquez, on a GP24, to take second place by a considerable margin.

It’s interesting to note that even Ducati, which has been at the forefront of MotoGP developments for years, can still misjudge a situation. By the way, Ducati has always told us that the 25 engine is basically the same as 24 and that they too are at loss as to why the other two riders struggle so much. However, both these riders often explained to us how difficult it was to get the 2025 bike

set-up in its ideal working window.

The few times that Bagnaia had a bike underneath him that worked well enough for him, like in Motegi and Sepang, he was suddenly superfast.

What we’ve also seen here is how much influence the character of a racing motorcycle can have on the confidence and, consequently, the performance of a top rider like Bagnaia who, after all, is a double world champion (on a Ducati).

With the engine development frozen for 2026, Ducati is not allowed to update the 25 engine. But, interestingly, they can revert to the 24! Will they do so? Be prepared to never find out because it will be looked at as a failure from their side, and so not something they will be too keen on telling us. Would you?

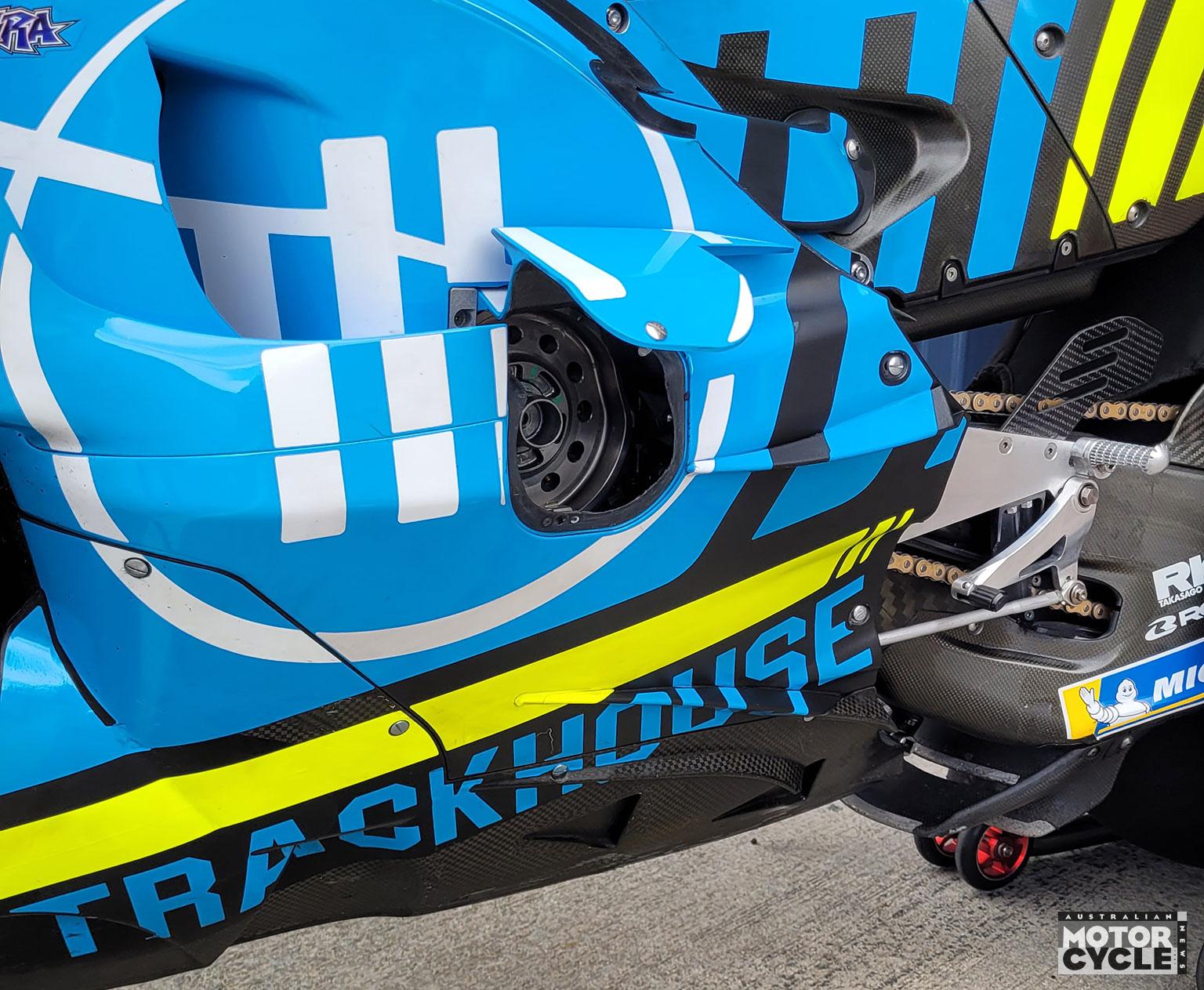

APRILIA – 4 GP wins

The Aprilia RS-GP finished third in the 2025 championship in the hands of Marco Bezzecchi, and together the Aprilia riders shared 24 podiums. That’s a whopping 15 bottles of podium prosecco more than they managed the previous year. But, weirdly enough, none of these successes came from Jorge Martin, the 2024 world champion who left Ducati to stick the No.1 plate on a ’Priller. Poor Jorge had a nightmare season where he crashed and hurt himself nearly every time he jumped on a motorbike.

Fortunately for the Noale-based squad, Bezzecchi stepped up very well to the role of No.1 rider and showed that he can be trusted in leading the development of the bike.

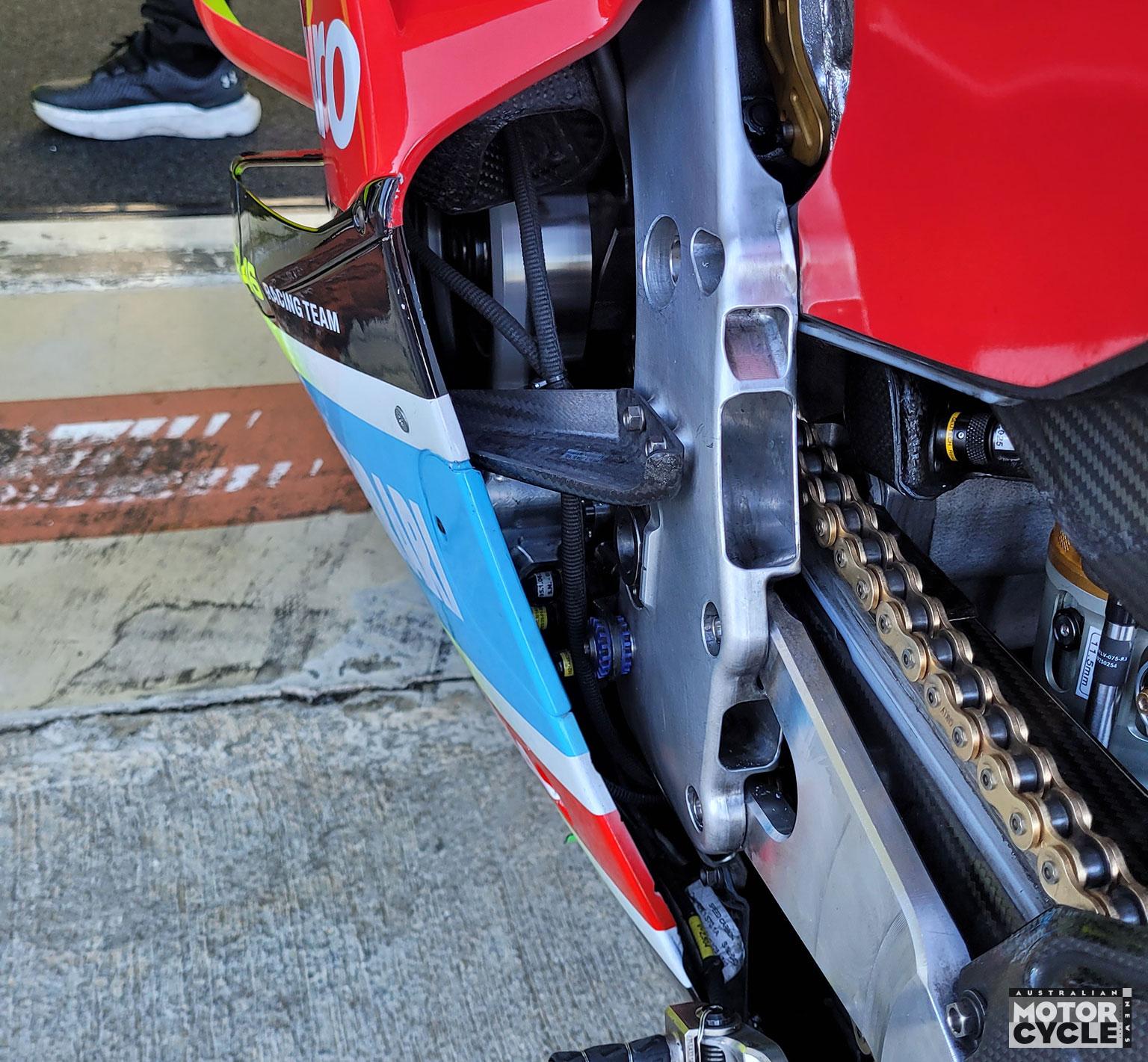

The 2025 RS-GP had improved stability during hard braking while turning in. And the techs achieved this without losing out on its already good aerodynamic package. They changed the balance, moving weight towards the rear of the bike, and added a totally new aero part just behind the rider’s legs. This added rear weight improved stability while the ‘leg wings’ helped keep the rear down. More load on the rear tyre meant it could assist more in stopping the bike.

Michelin’s rear tyre is a lot better than its front tyre, forcing manufacturers to design their bikes to make more use of the rear. Although this seems an easy fix, it is actually very difficult to make such a big change to a bike without losing the all-important front feeling. Aprilia clearly managed this well.

The aerodynamics too were revised, retaining their strongpoint ground effect, but now with reduced overall drag and increased stability. Together, these changes made the 2025 GP-RS not only easier to ride but also less sensitive to differing track layouts.

Ground effect is created by having a flat part of the side of the fairing close to the ground at high lean angles. This flat part is then not parallel to the track but bends away, speeding up the air between track and fairing, which in turn decreases the pressure, thus ‘gluing’ the bike to the track on a vertical angle – which is exactly what will allow higher corner speeds.

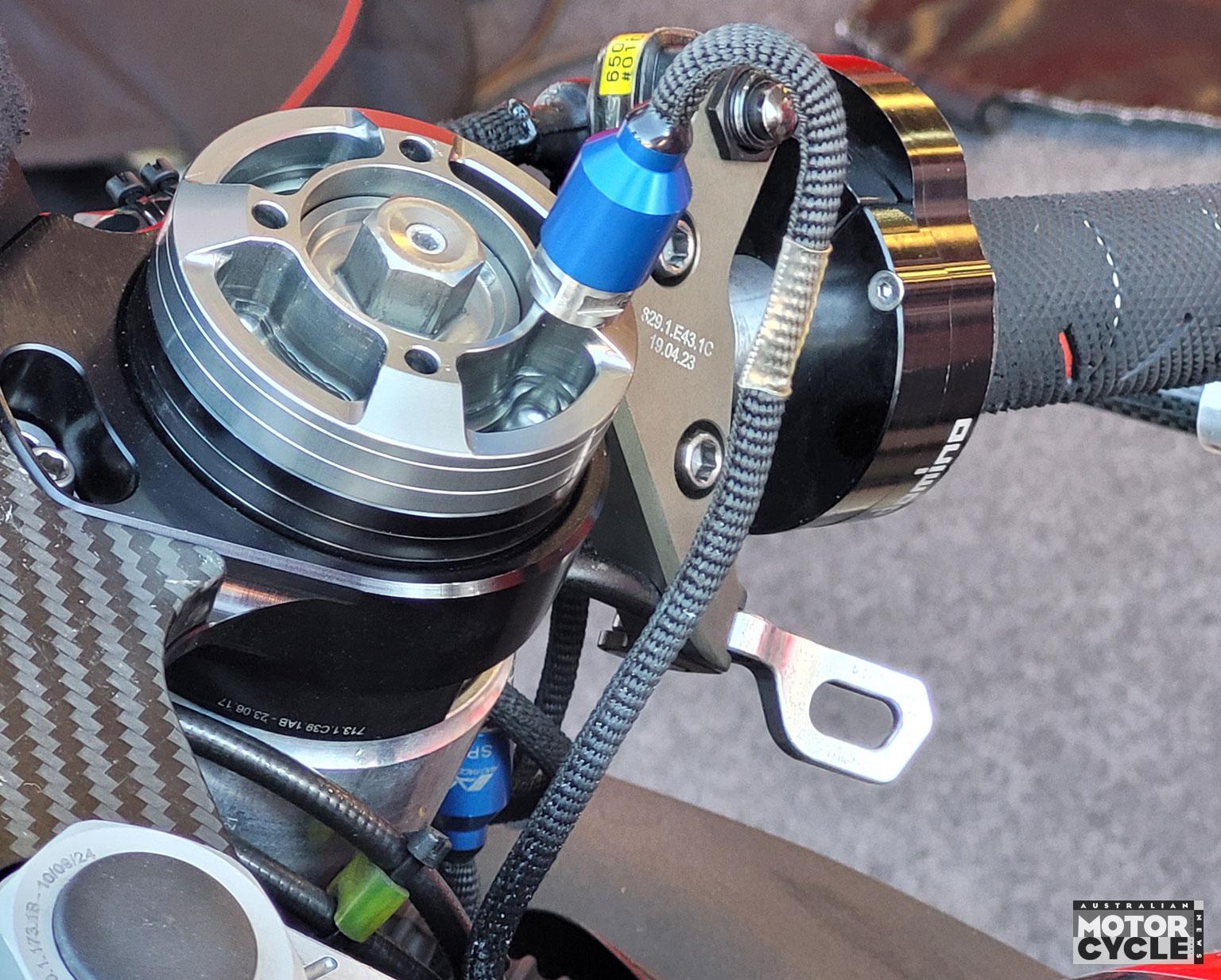

Starts too have improved. Gone are the days when Aprilias lost often an entire starting row on the way to the first corner. The carbon clutch plays a huge part in getting off the line consistently and fast. Carbon has a high coefficient of friction, so the whole package can be made neat and light. But the friction of carbon depends a lot on the temperature. This used to be a problem for consistent feedback and performance but, somehow, Aprilia now have its starts sorted.

Aprilia now has what’s considered by many to be probably the best bike on the grid. Yet techs still brought lots of parts to assess in Valencia. Most of the test work was done by Bezzecchi, while Martin worked on regaining his confidence, learning how to get closer to the limits of the RS-GP. Most of the testing was done trying new aero.

Having a very competitive bike is nice – but making sure it stays competitive is bloody hard work that will continue at Sepang.

KTM – Zero GP wins

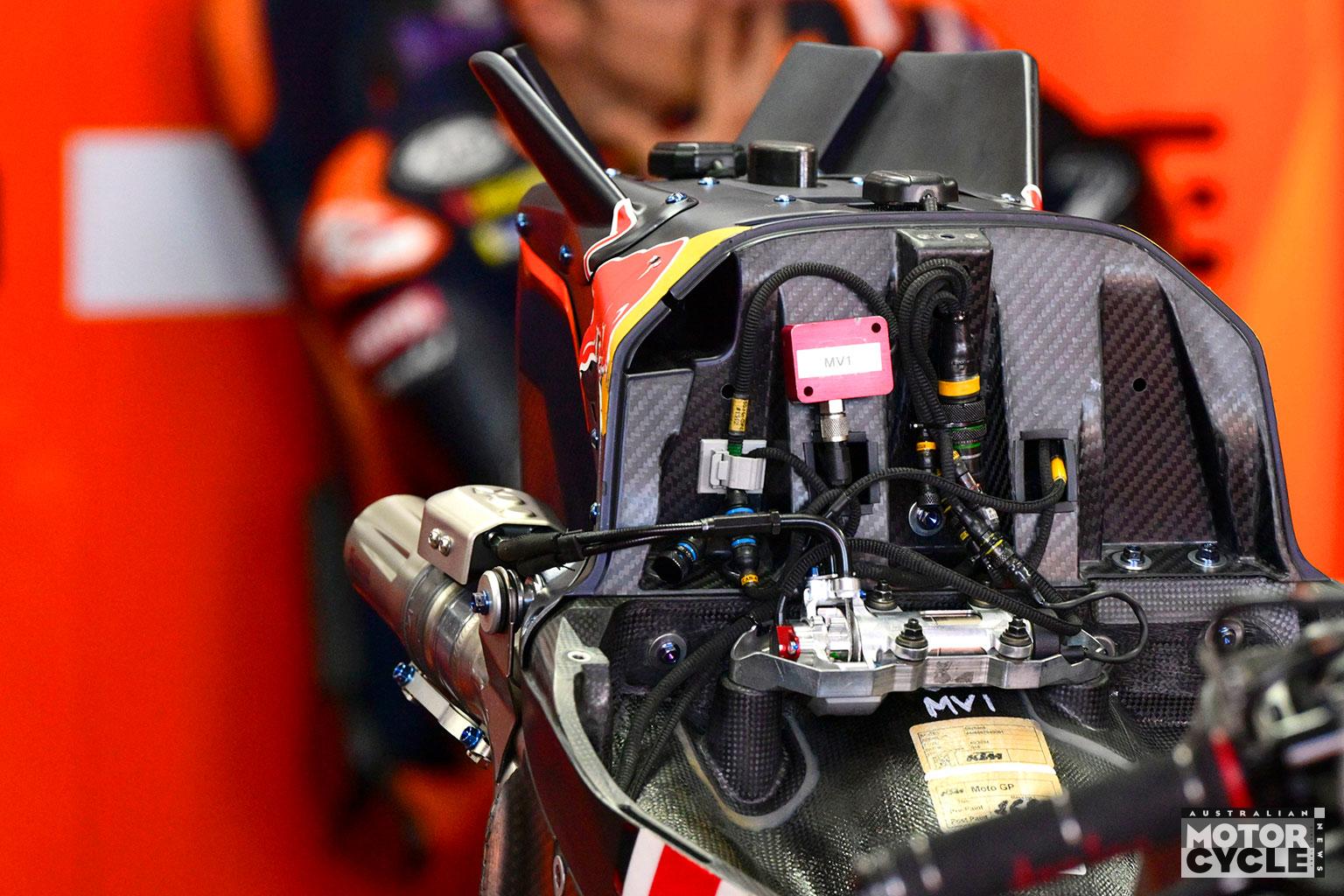

A total of 12 podiums and a fourth position in the standings for Pedro Acosta, who somehow forgot to take his first win in 2025, sums up a hard year for KTM.

The RC16 used to lack edge grip; it under-steered and it was eating its tyres way too fast. The bike also needed careful initial braking, where the brake pressure had to be built up gently. Hard, aggressive braking made the bike pitch forward – which means the rear tyre couldn’t be used for stopping effectively.

Economic problems at KTM made for a troublesome European winter. Development was limited and key people were leaving the company. KTM looked in real trouble.

The season was started with a new version of the unique carbon chassis (only KTM uses this!) and an improved engine, all thanks to the work the test team did in 2024. The starts were always a strongpoint of the RC16 and 2025 would be no different, with the orange bikes usually gaining lots in the drag race to the first corner.

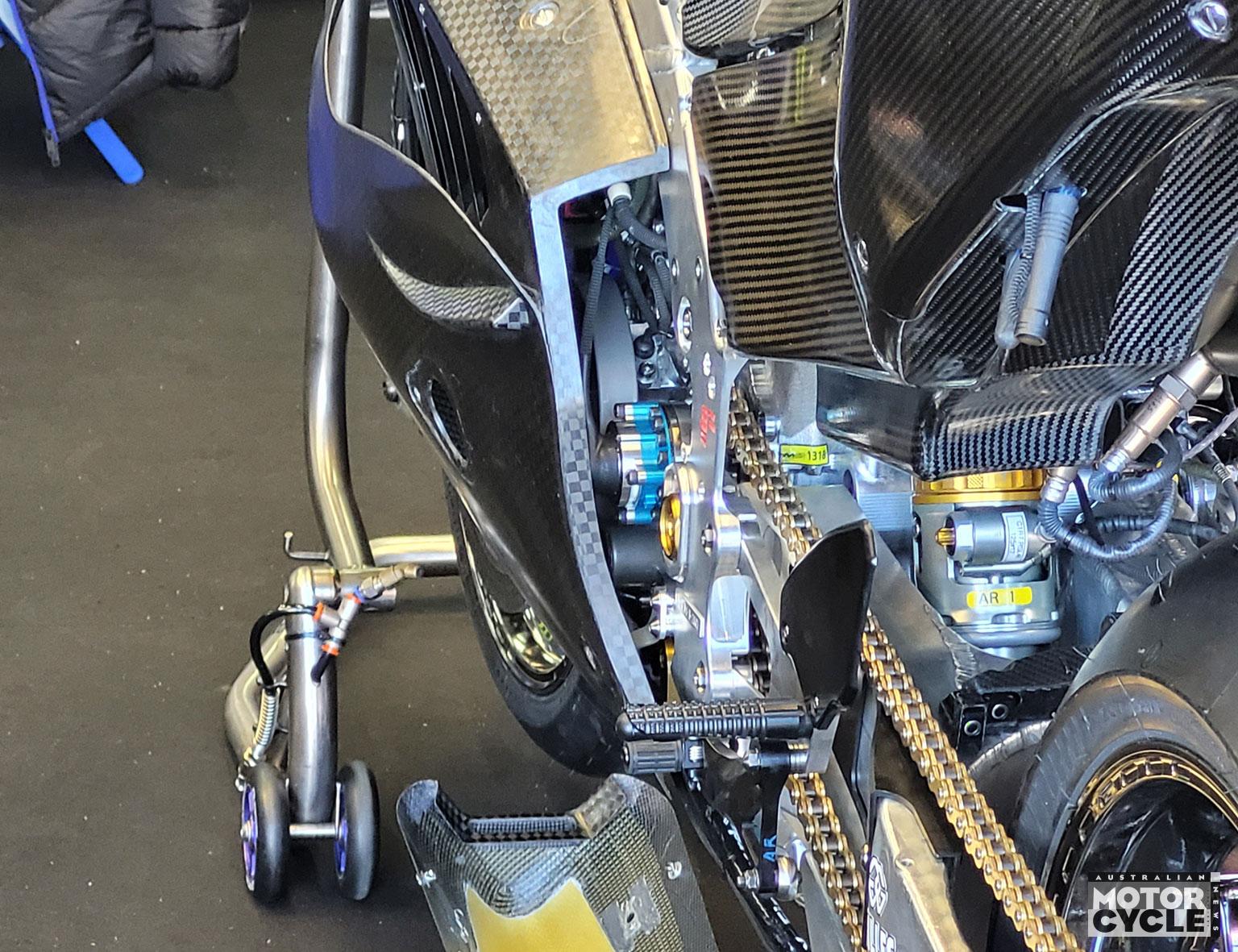

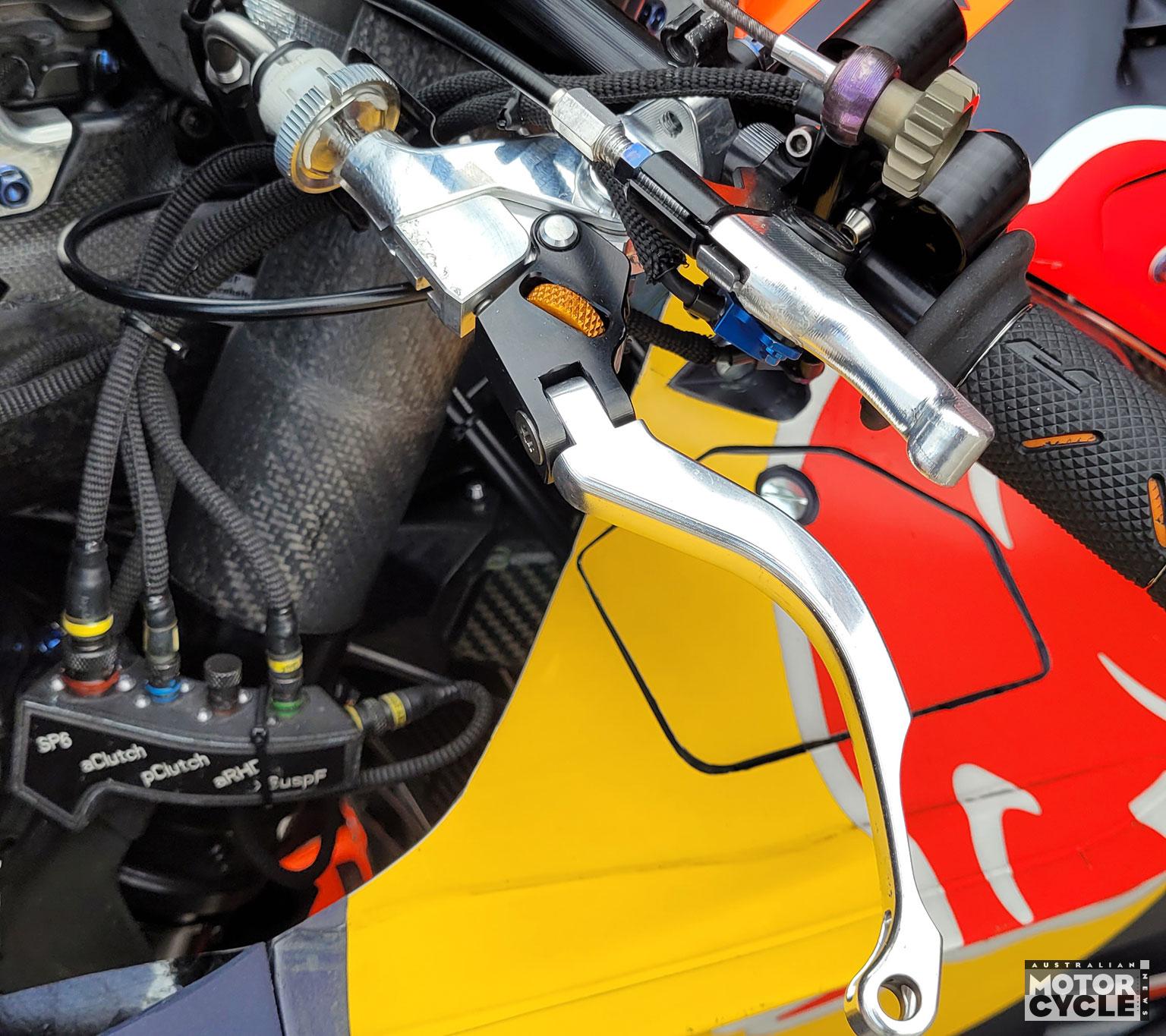

A tuned mass damper was rumoured to be inside the newly shaped seat unit – something KTM has had no experience with but clearly needed to, in order to get rid of the chatter that hampered them the previous season. Being close to the Red Bull F1 guys must help them, as tuned mass dampers were first used in F1 before being banned there. From the Misano test onwards, KTM (just as Ducati) were seen with a small vertical mass damper at the end of the swingarm. It’s there to calm the vibrations coming from the rear tyre. It contains a shock absorber type of piston that functions both as a hydraulic damper and a mass damper. It’s held in the middle by springs on both sides and filled with oil. Adjustments can be made by changing the mass, the springs and the shims.

Finally, now KTM too is using an exhaust valve, located at the end of the top exhaust. Controlling the flow of the exhaust gases helps with fine tuning the engine brake performance.

Initial results were not great until Maverick Vinales and his crew chief Manu Cazeaux discovered that moving his position on the bike a serious 60mm backwards transformed the RC16. It allowed him to be fast by being smooth – something they had not realised was even possible before. Acosta keenly followed Vinales’ example and it helped him turn his so-so season around.

Midseason brought an aero update that improved stability through the longer corners. A new swingarm improved acceleration by dampening out the pumping that would occur at the rear end. WP, KTM’s suspension company, developed a new damping character in the fork.

To take the next step forward, the RC16 needs more grip while fully banked over, and to stop wearing out both tyres so fast.

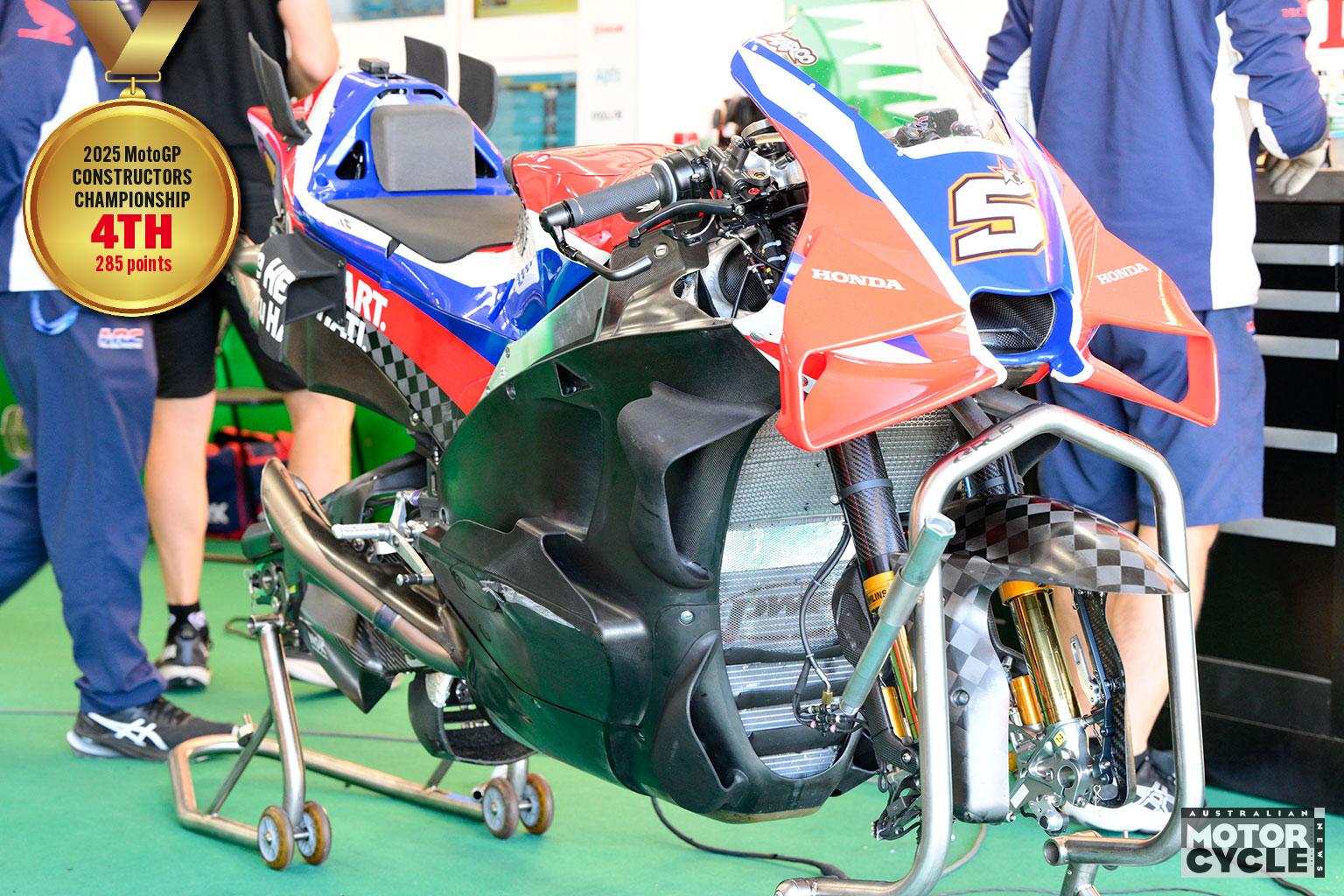

HONDA – 1 GP win

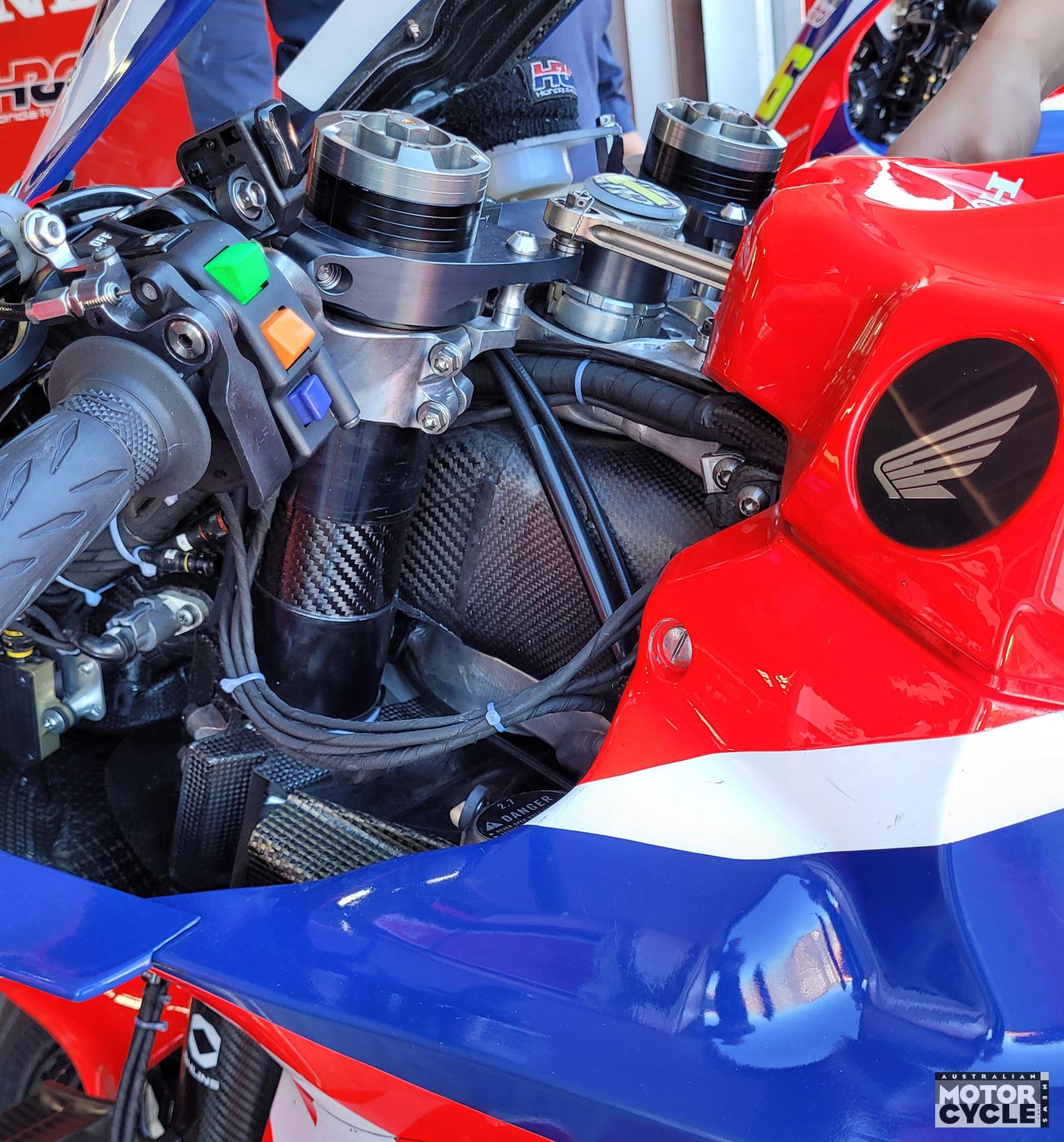

It is in the DNA of the Honda RC213V to be good at trail braking – diving into corners while still carrying lots of front brake, pressing the front tyre into the tarmac while making the bike turn in – and the 2024 version was no exception. But it was also the only thing it did reasonably well. The Hondas were using up their tyres too fast, a tendency to understeer made it slow through longer corners and it lacked top speed. With Honda’s V4 being nearly as slow as Yamaha’s inline four, that must have hurt the proud HRC hierarchy.

Which it did. Enough for Honda to step over their pride and convince Aprilia’s technical director Romano Albesiano to join them as their new technical director in 2025.

The results of Albesiano’s more modern approach came quickly and in an unexpected way. By simply making new combinations of existing parts and then testing them thoroughly, the bike got better and, more importantly, the direction for the next developments became crystal clear.

Helped by the concession rules, Honda was allowed to test more – and this clearly paid off. During the season a constant stream of parts flew in from Japan. Various chassis and swingarm variations, plus lots of different aero parts were evaluated and, more often than not, stayed on the bike.

Chassis and swingarms make up for most of the shock absorbing when a bike is at a high lean angle. At midcorner, track irregularities are coming into the bike on a vertical axis while the bike has an actual banking angle of 50 to 60 degrees.

In a perfect situation, the resulting bending of the chassis parts makes both wheels turn-in some more but if not, the bending of the chassis will make the wheels point towards the outside, causing the bike to ‘understeer’ and making the cornering radius wider. A fine line to tread.

Next on the list was the software strategy for the traction control. By interrupting the power less and placing more of the slip control back in the hands of the rider, the bike’s feedback became easier to understand – and with that, faster over the race distance.

Also, thanks to the concession system, Honda brought some significant engine updates during the season and the results showed: two Hondas topped the list of highest average top speeds at the last round at Valencia. In current MotoGP, top speed doesn’t do much for the laptime but it is all-important when fighting for positions.

What is still missing at Honda is an automatic activation of the rear ride height device, and having a lighter carbon swingarm.

LAST DECADE OF MotoGP CONSTRUCTORS WINNERS

2016 Honda

2017 Honda

2018 Honda

2019 Honda

2020 Ducati

2021 Ducati

2022 Ducati

2023 Ducati

2024 Ducati

2025 Ducati