Flettner rotor wings for bikes use the Magnus effect to create variable downforce levels

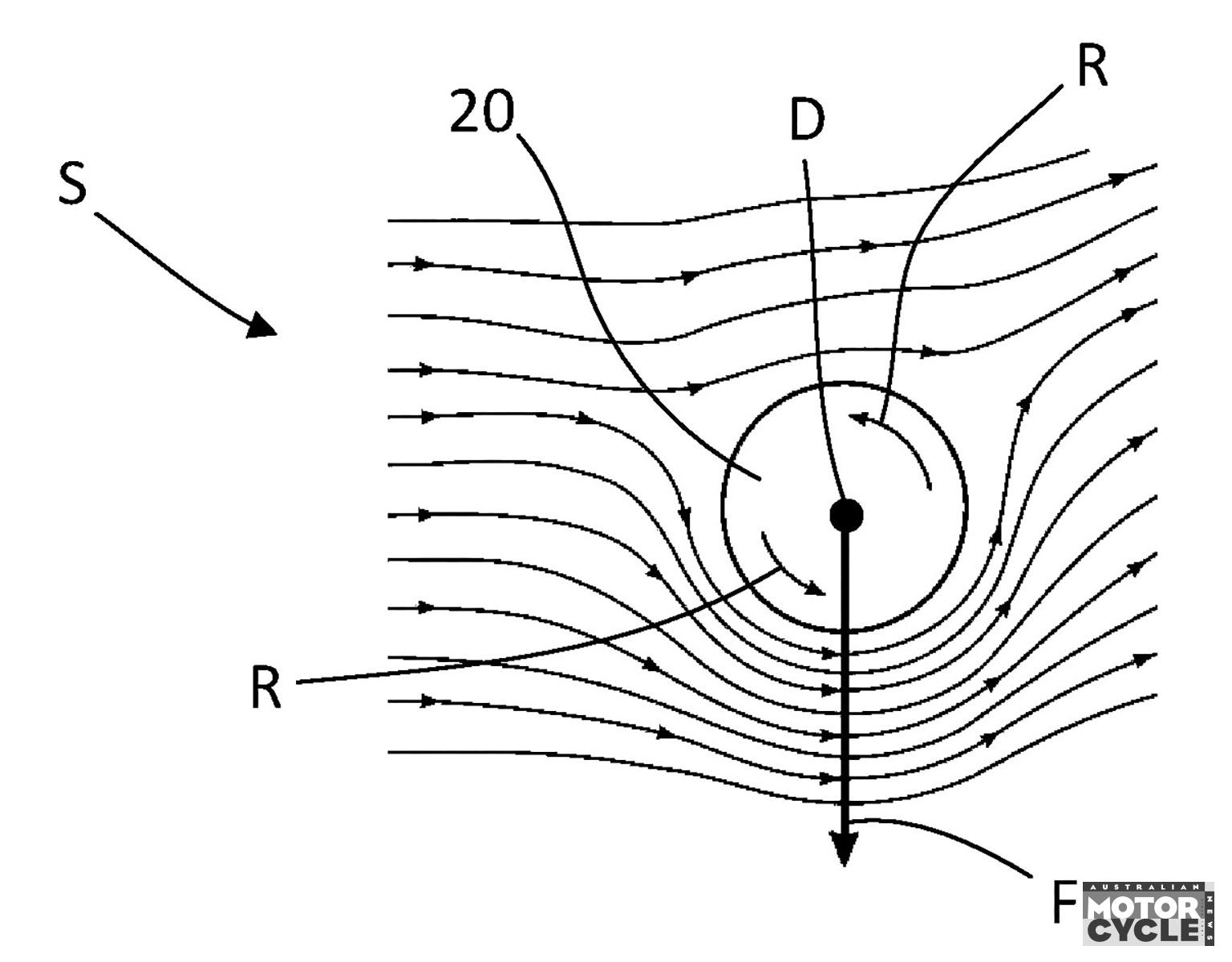

Just over a century ago, German inventor Anton Flettner revealed his eponymous invention – the Flettner rotor – as a replacement for conventional canvas sails on ships. Based on spinning, vertical cylinders, they were first demonstrated in the 1920s and use a phenomenon called the Magnus effect to influence airflow passing over them – creating a pressure difference that pushes them in the desired direction.

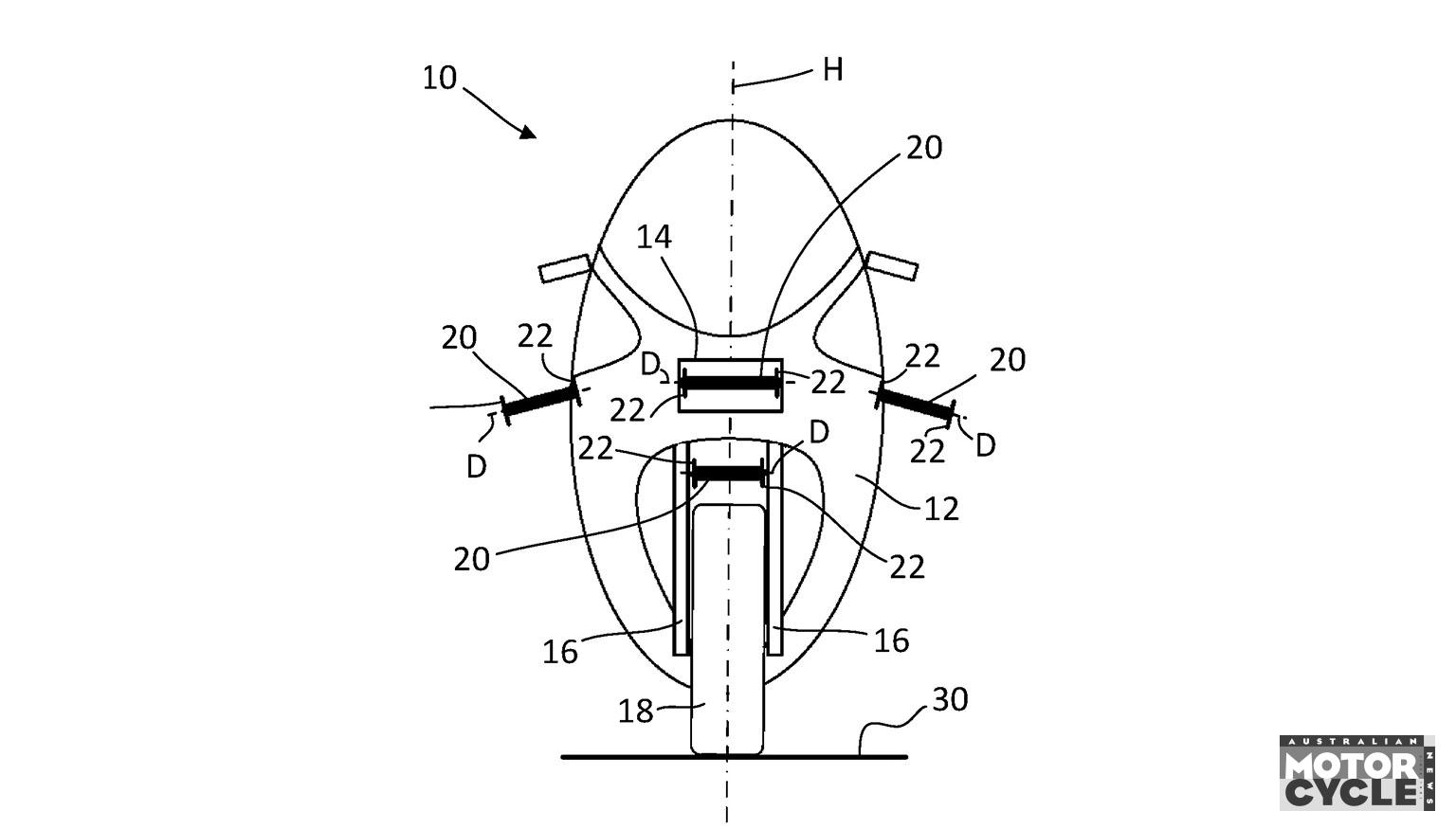

Now BMW is looking at using the same idea to replace wing-shaped aerodynamic components on motorcycles, as revealed in a new patent from the company.

The Magnus effect was demonstrated by Heinrich Gustav Magnus – another German, this time a physicist – back in 1853. He showed how a rapidly spinning cylinder exposed to airflow would create low pressure on one side and high pressure on the other, just like a wing. It was already a known phenomenon even then, though, with Isaac Newton having explained how the same process affected spinning tennis balls to alter their path through the air back in the 17th century. Flettner’s rotors, however, found a practical use for the idea, and today in the 21st century the idea is having a resurgence, with a growing number of ships adopting Flettner rotors as sails to assist their conventional engines and improve their efficiency.

BMW’s idea is to use the same concept to address one of the problems associated with fitting winglets to motorcycles – namely that the downforce that a conventional, unmoving winglet generates isn’t always what’s needed on a bike that’s constantly changing speed, pitch, roll and yaw.

The patent suggests small Flettner rotors, around 20 cm long and 4 or 5 cm in diameter, mounted on either side like the winglets on existing bikes. It also suggests another could be fitted between the fork legs, along with one in the air intake on the bike’s nose, and a fifth on the tail of the bike to create rear downforce. Each would spin at between 50,000 rpm and 100,000 rpm, with BMW suggesting that 80,000 rpm is the sweet spot to maximise their performance. Electric motors in the base of the rotors would be used to spin them.

But what makes them better than normal winglets? There are a few advantages to be had.

First, the rotors aren’t sensitive to the bike’s pitch. A fixed front winglet might help prevent a wheelie, but if you overcome its downforce and lift the nose of the bike anyway, it becomes a sail that catches the wind and could make the bike more wheelie-prone, rather than less. The Flettner rotor isn’t affected by changes in pitch, so if it’s spinning forwards, accelerating the air below it and slowing the airflow above, it will continue to provide downforce even if you’re wheelieing.

Second, the rotors’ speed can be changed independently of the bike’s speed, potentially allowing for more downforce when you’re going slowly – accelerating out of a corner, for example. And when you’re flat-out on a straight, with no need for downforce and the accompanying drag that comes with it, the rotors’ spin can be stopped, reducing the drag to improve top speed.

Thirdly, the rotors’ direction can be changed. That means those side-mounted ones could spin in opposite directions during corners – the outer one given topspin to create downforce, while the inner one spins backwards, pulling the nose of the bike towards the apex.

While similar benefits could also be achieved with variable-pitch winglets, as demonstrated recently on CFMoto’s upcoming 1000 cc V4 superbike, the Flettner rotor idea could be easier to control and use a lighter mechanism than the powerful actuators needed to move wings against the pressure of air.