A former champion racer turned classic bike importer, restorer and industry cornerstone, Jon Munn created his successes the old-fashioned way

The moment I realise why Jon Munn has been so successful in the classic bike game doesn’t come while he’s telling stories about his title-winning drag racing days, or while we’re weaving through the rows of rare machines in his Seaford warehouse, 40-odd kays south-east of Melbourne. It comes in the final five minutes of our hours-long interview.

Half a dozen people have wandered into the warehouse, meandering through the scores of classic and collectible motorcycles, pointing and talking to one another as they would in a museum or gallery, rather than with the intent to buy. It turns out one of the couples has made the trip to Classic Style Motorcycles to pick Jon’s brain. The wife has a photo on her phone of her recently deceased father sitting astride a motorcycle in what she thinks was the 1940s, which she hopes Jon might be able to identify.

As he zooms in and out of the photo on various sections, talking aloud his deductions and calculations as to why it wouldn’t be this, that or the other, the husband is excitedly relaying stories to Jon about all the motorcycles he’s owned over the years, even illustrating his tales with his own phone photos held up in front of Jon’s otherwise-occupied face.

But instead of fobbing the couple off with a polite indifference, he emails the photo to himself, notes down the wife’s phone number and vows to do some research on her behalf – all while meeting the husband’s enthusiasm for what is frankly a rather underwhelming collection of bikes, and even throwing in his own jokes and anecdotes to the delight of them both.

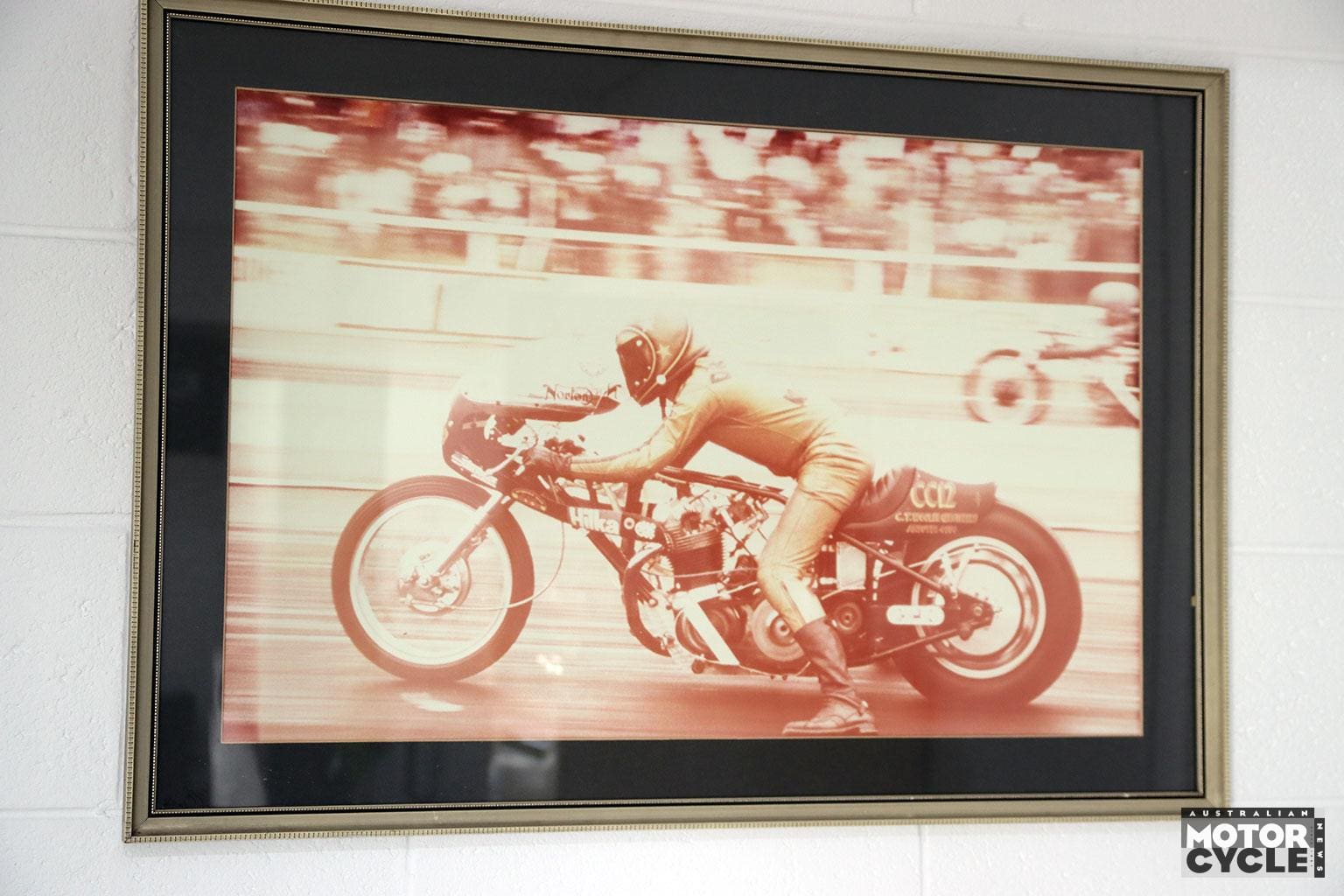

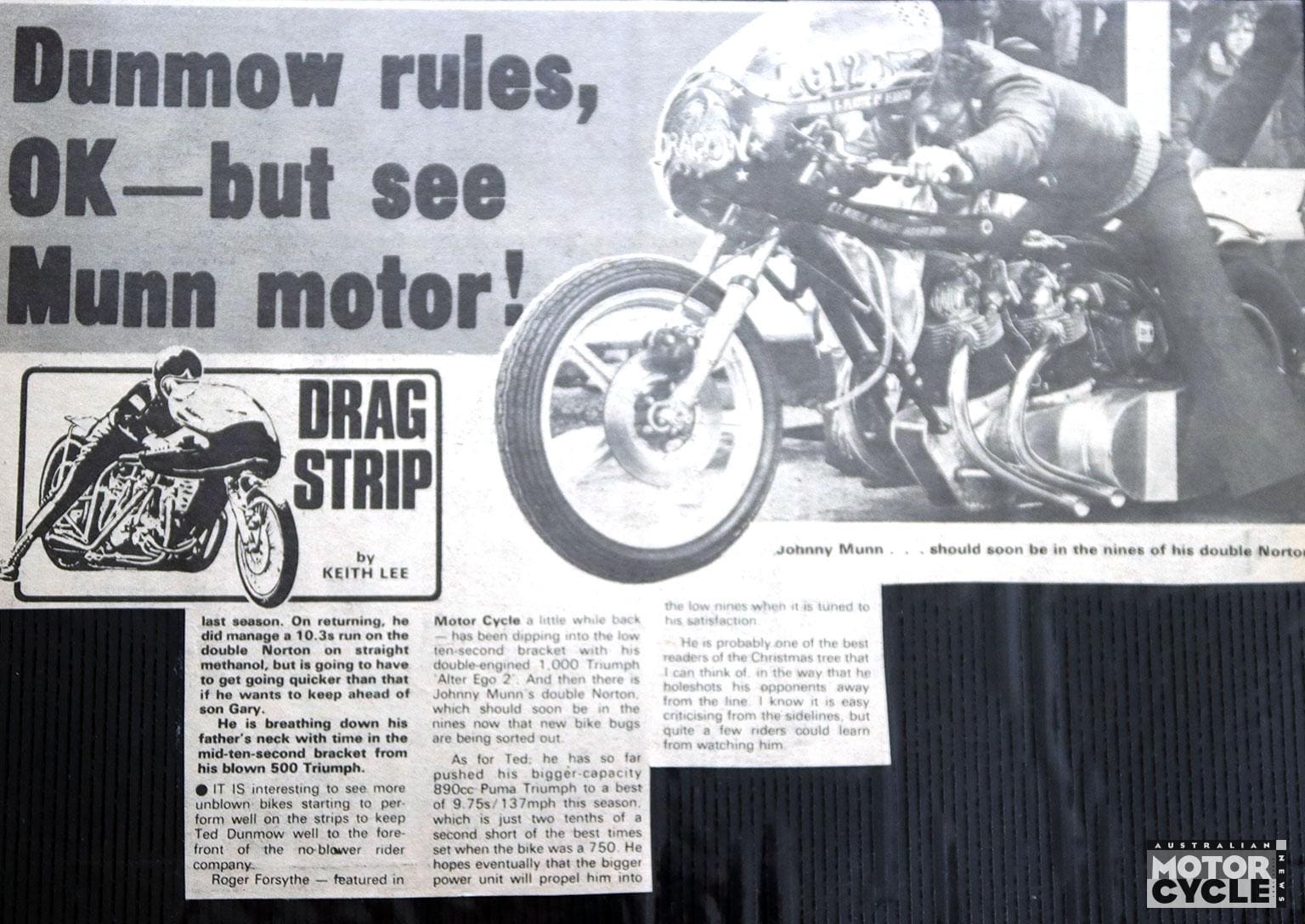

Jon’s been in the classic bike game for three decades now. Long before he was the softly spoken custodian of what must be at least a 400-strong collection in Seaford, Jon was flat-out on the quarter mile aboard a home-built, twin-engine Norton that would eventually take him to the very top of British drag racing in the late 1970s.

“I won the championship on that in 1978,” he says, pointing to a photo of the double Norton. “And then I sold the bike and had a year off before I started racing with John Hobbs.”

I ask him how he got into drag racing in the first place. “One weekend, some friends of mine were going to a party in London,” he tells me. “So we all went together – this was in 1972 or ’71 – and then the next day, they said we’re going to go to Santa Pod to the drag racing. I thought, that sounds like fun, so we all went. And I got bitten by it, and then I came back and built a bike.”

Jon shows me a photo of that home-built Triumph-powered drag bike sitting in a modest English backyard – the very first he ever raced. “I was on track racing for just over 200 pounds,” he says. “That included a secondhand set of leathers, a new helmet and the bike we built.”

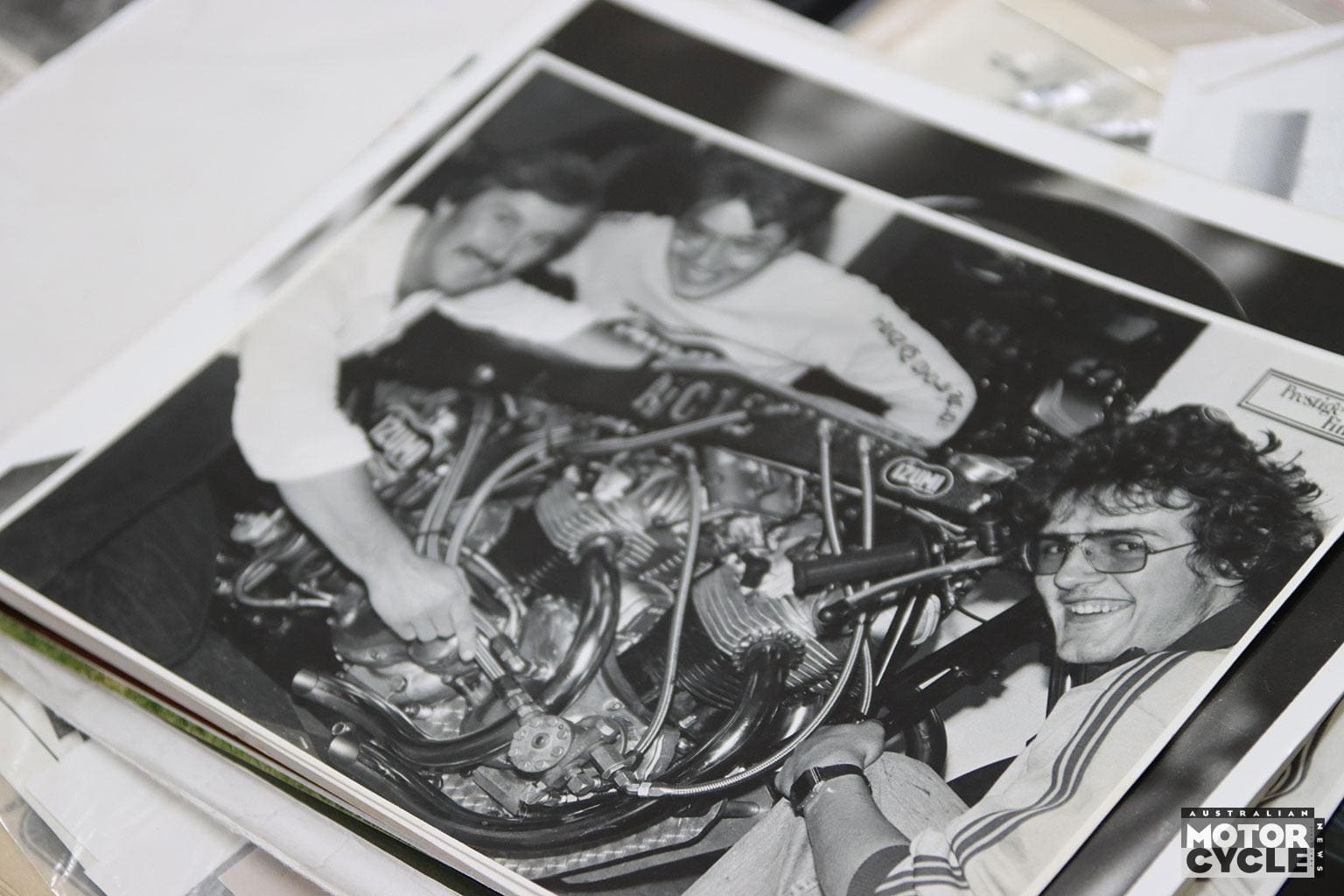

Over the years that followed, he refined his designs and self-tuned his machines using a mix of feel, instinct and calculation to end up with the Norton. “I even used to work out the gear ratios and all that sort of stuff,” he replies when I ask how he’d calculate the steering-head angle. “It’s all quite scientific. But it’s all computer-operated now. We were analog.”

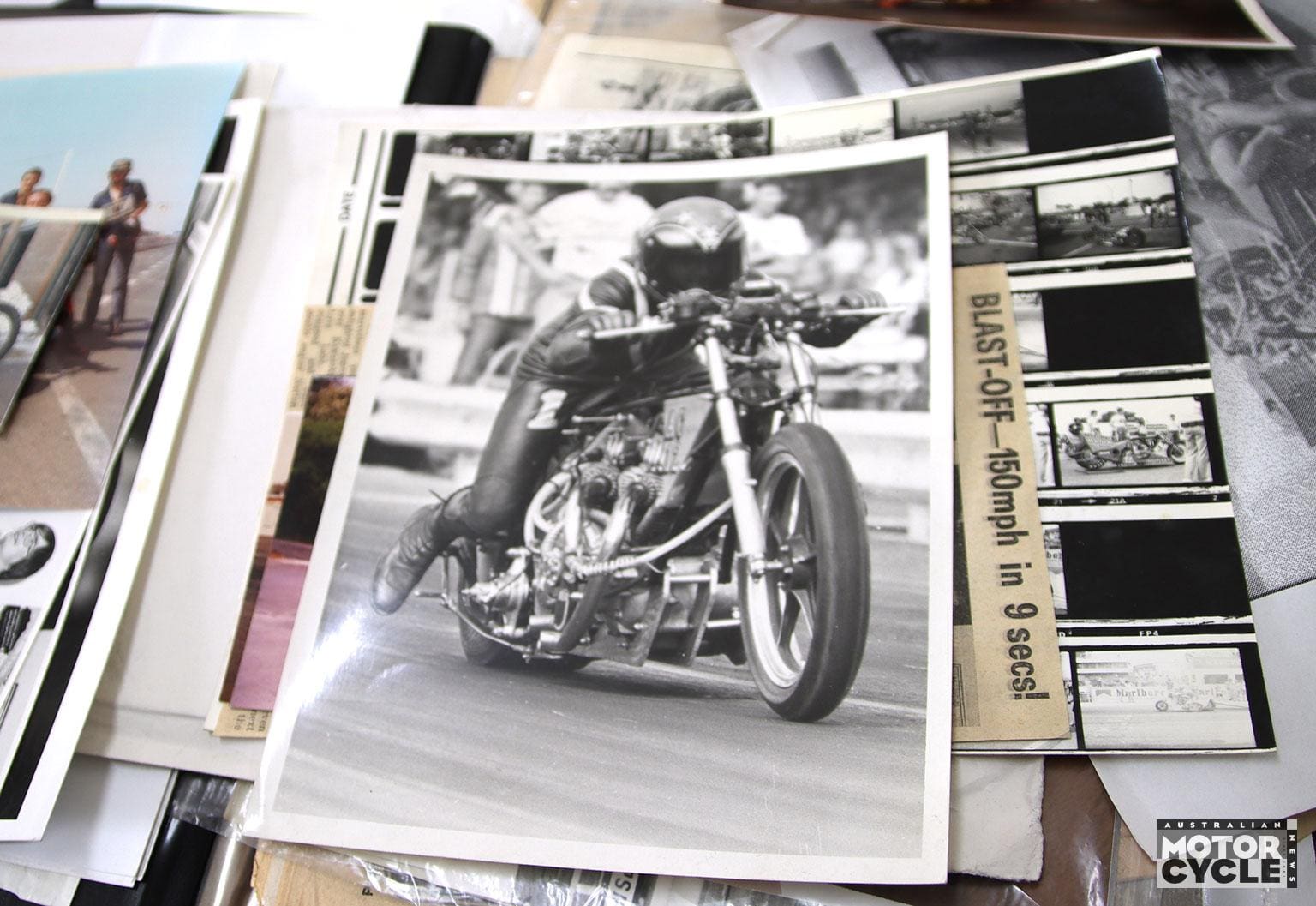

The championship-winning Norton would go on to set a new record as the fastest naturally aspirated British bike of its time. “Ted Dunlow held it for years, and then I took it with that old thing,” Jon smiles, handing over a photo. “I was nearly at the top of the strip there and still smoking the tyre.”

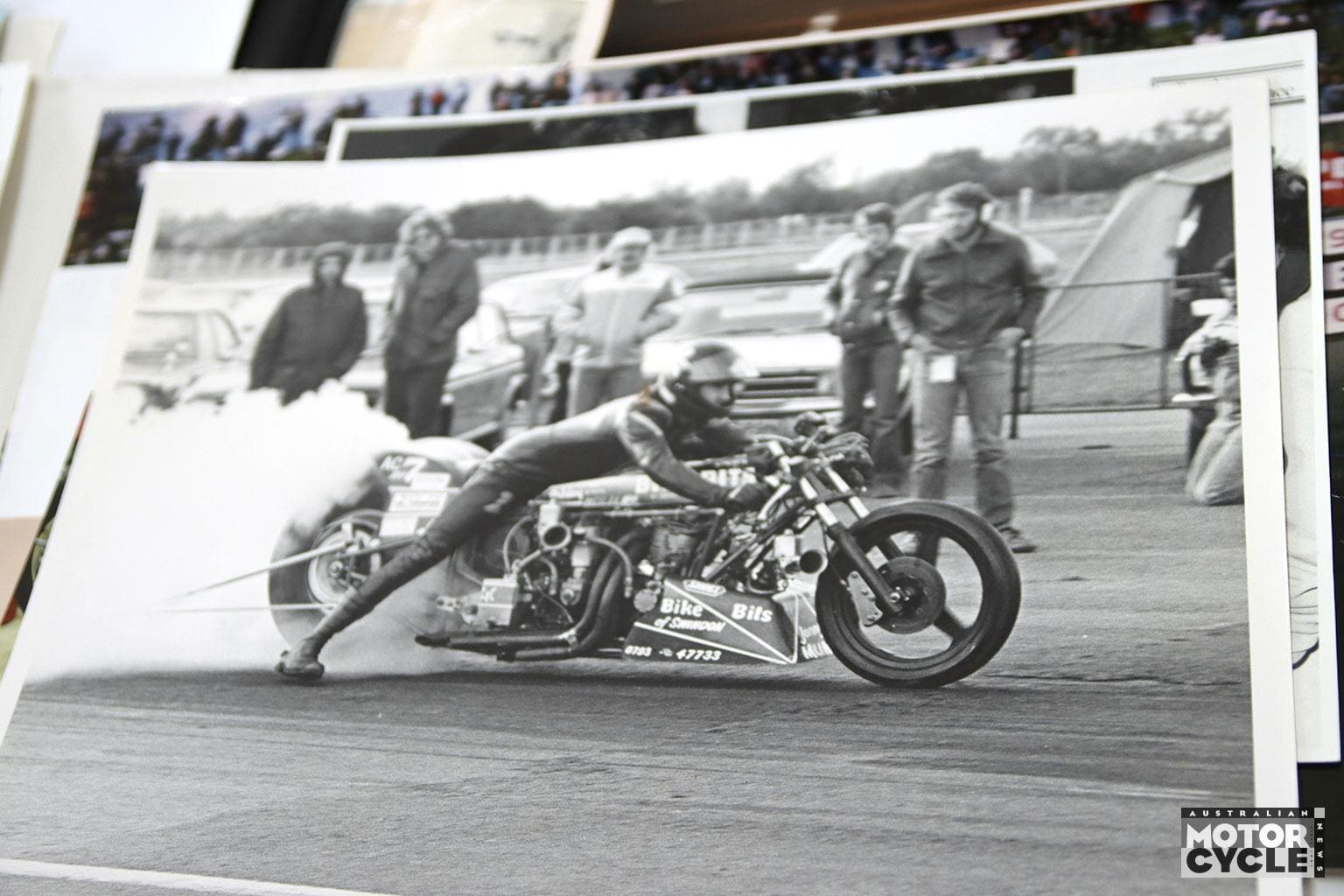

After clinching the title in 1978 and taking a year off, Jon returned to the strip with even bigger firepower, this time as the rider of The Hobbit, a twin-engine, eight-valve Weslake beast built by legendary UK drag racer John Hobbs. The two had gone head-to-head in their racing days, with Jon one of the few riders able to beat Hobbs off the line. That played a part in Hobbs later asking Jon to ride The Hobbit, a gesture that speaks volumes in the world of competitive drag racing.

In one image – a personal favourite of Jon’s, and it’s easy to see why – he’s stretched out and launching hard, the sheer power of the supercharged 1700cc twin-engine bike visible in the warped sidewall of a slick so wide it looks borrowed from a drag car.

“That’s hooked up!” he says.

That bike, and Jon’s skill, would earn him one of drag racing’s highest accolades.

“The 1980 one was televised, and we won that,” he says. “That was the 1980 World Finals. That’s when I came over here to Australia for the three-month holiday after I won the World Finals.”

He brings up a YouTube clip of the broadcast he’s talking about and, despite being 45-year-old footage, the engine still sounds fearsome and the speed in which the grainy clip shows Jon slingshotting from one end of the quarter-mile to the other is still mindblowing.

“It’s a three-speed underdrive and it’s all hydraulically operated,” he explains. “You just literally press buttons. You do the burnout in top gear, then to reverse the bike, you have to pull the buttons back… and then you launch in first, and you’re literally pressing for second as you leave the line almost.”

There’s pride in his voice, but not nostalgia. “You can’t go on forever,” he says, matter-of-factly. “Essentially, you know, we all get older.”

And after decades of racing, restoring and dealing in rare bikes, Jon’s starting to think about what comes next. “I’d like to retire at some point,” he says. “But I need the right person to take this over.”

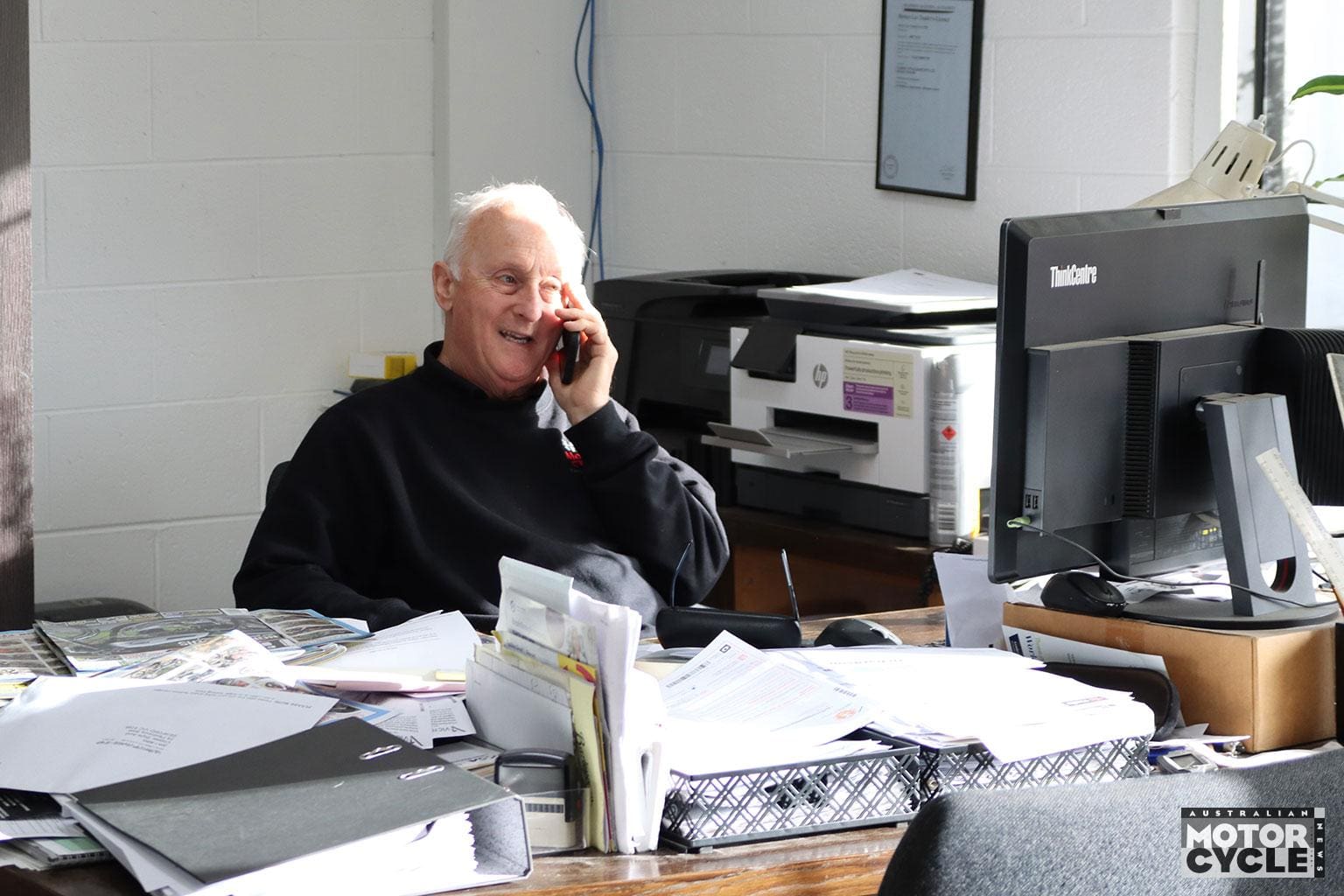

That’s no small ask. Classic Style is a bike shop that’s part museum, part workshop, part archive, and entirely the result of his dedication to collectible motorcycles, rare imports and fastidious restorations. And you only have to listen in on just one of his phone calls or dealings to appreciate just how much knowledge and experience he’s garnered in this space over the decades. He’s still there each day, fielding calls, sourcing parts, arranging shipping and meeting visitors at the roller door with the kind of welcome that’s increasingly rare in motorcycle businesses these days.

Classic Style started as a trickle of imported bikes and soon became a steady stream, with demand fuelling the scale of the operation. But even as the business grew, Jon wasn’t content to leave racing behind altogether. Years after stepping away from the drag strip, he turned his hand to sidecar motocross. Just as he did in the ’70s in Britain, he built a Norton-powered machine that took him and his now retired former bike restorer and workshop manager Geoff Knott to a Victorian championship.

“God, that bike was so quick, ’cause I used to build Norton race engines years ago,” he nods. “That was such a quick Norton. It really was.”

Today, as we weave through rows of tightly packed motorcycles – mostly British and Japanese, and ranging from over 100 years old to barely 30 – it’s clear just how dominant Classic Style has become in the classic bike game.

Jon says sourcing the bikes has never been an issue, as long as you know where to look.

“We don’t get much from here,” he says. “We get it all from overseas because that’s where they are. You go back 40, 50 years, the population here was about 14 million and America was getting close to 300 million. They had huge operations over there; Triumph America and everything else. Everything was sort of there. So it makes sense.”

Quarantine, however, was another story. “We used to bring bikes in through Melbourne,” Jon explains. “The trouble is, they’d get unpacked up there at the docks, and then we’d have to get 40 bikes back here afterwards. And it was a bloody nightmare.

“So I thought, damn it, I’ll bite the bullet. I bought the factory next door and we set it up as a QAP.”

That second building now operates as a Quarantine Approved Premises, allowing Classic Style to handle customs, unloading and inspections on site.

“So when a shipment comes in, we do the customs clearance and everything, and we do the quarantine clearance. We have the quarantine direction for the container to come here. We unpack it here, put them in the quarantine room, and then an officer will come out and just check them and say, yeah, fine, and release them.”

That shift streamlined operations and gave Jon more time to focus on running the business.

Of course importing classic motorcycles from halfway across the world isn’t without its challenges. A recent legal dispute involving an overseas logistics partner saw Jon lose a significant number of bikes. And, just like he found a solution to the quarantine ‘nightmare’, he’s dealing with this one with a surprising sense of calm and self-belief.

“I’ve got my finger on the pulse, I’ve just got to keep the pressure on. See if we can make it happen.”

That tenacity has served him well through the changing whims of the motorcycle market, too.

“Back when we started, it was all British bikes,” Jon says. “Bonnevilles, Nortons, BSAs – that’s what people wanted. But the market’s changed. Now everyone’s after Japanese bikes; Honda fours and that sort of thing.”

It’s a shift that Jon has met, adapting his stock and sourcing strategy to reflect what today’s buyers are chasing. While there’s still a healthy appetite for British classics, especially among older collectors, he’s seen a clear generational pivot towards Japanese machines. And Classic Style’s ever-rotating showroom tells the story; rows of Hondas, Kawasakis and Yamahas lined up alongside Vincents, BSAs and Triumphs.

“We’ve always worked on the idea that there’s a bum for every seat,” Jon says. “You just have to find them.”

That philosophy applies just as much to the showroom stock as it does to Jon’s own collection, which he points out as we walk through the impressive space.

“These ones are mine,” he says, gesturing to the Velocette Thruxton, a BSA Rocket Gold Star and a pristine 1959 Triumph Bonneville. “All through here, and most across the back… probably 25 or 30 in total.”

Among them is a custom Metisse he built as a tribute to the Rickman brothers.

“But we spiced this one up a bit,” he grins, his enthusiasm as clear as day. “It’s got a five-speed cluster in it, electronic ignition, Bob Newby (Racing) clutch and belt drive. We had an aftermarket twin-carb manifold, so we put twin carbs on it. So it’s got the works and it’s a great little bike, it really is. I took that down to Bayles the other day to the link run and it flies along, it really does.”

I ask him if there’s any bike he’s always coveted but has never been able to acquire.

“There’s nothing yet,” he says. “I’ve got two Vincents in the office. One of them is the only White Shadow in the B Series – they only built 76 B Series Shadows, and that’s the only White Shadow. That’s a very interesting bike and I’ve got my ‘riding’ Rapide, that’s lovely.

“And the other one in the office is my little NSS Velocette Rolls Royce. It was the last one ever built. You look in Ivan Rhodes’ book on Velocettes; there were six built in 1970, and that was the sixth one.”

I ask him if the British bikes are where his heart really lies, to which he immediately replies: “Oh, I just love them,” before pointing to two red Royal Enfields at the start of one of the rows. “This is the bike I really wanted when I was 16; the GT250. And I couldn’t afford one. They were the fastest 250 on the road at the time. And they were just under 400 pounds. I mean, I bought my Bantam for 40 quid. I always wanted one… they just looked fabulous. And now I’ve got two!”

It’s hard to imagine Jon not being part of Classic Style into the future, but that’s his goal over the next few years so that he and wife Maggie can enjoy their retirement together, without the demands of the business competing for his attention.

“I’m 75 in August, and I’d just like to be able to travel and ride my bikes and not have all the worry of… I mean, the trouble is, when you’re doing something you love, it’s very hard to walk away.”

It’s a reminder that what he’s built is rare, and that the right person could walk into something pretty special; two freehold properties, a globally recognised name, a well-oiled importing system and a deep reserve of hard-won knowledge – an opportunity that doesn’t come up every day.

And maybe that’s the real magic of Classic Style. Not just the squillions of dollars worth of bikes that have passed through the place over 30 years, but the man behind it all – the bloke who has broken records, lofted championship trophies and still takes the time to help a stranger identify a bike from a blurry black-and-white photo. For all his mechanical skill and competitive grit, it’s Jon’s generosity, curiosity and infectious passion that really defines the place.

It’s well worth the visit – but if a change of career is on the cards, there just may never be an opportunity like it again.