It takes a good engine and handling package to win a race, yet most racers would trade their sister to have an engine more powerful than their opponent.

Besides passing, having an abundance of power can be used to advantage in a number of other ways, too, such as placing less stress on the tyres during a race, or perhaps just to keep pace with the other riders. But the racer’s deal is, when you’ve got it – you’ll use it!

The iconic Britten bikes were one such machine, and while the motorcycle was a stunning piece of kit, the New Zealand-built engine was the life and soul of the bike. Just to see and hear one start up draws a huge crowd – it’s an event not to miss.

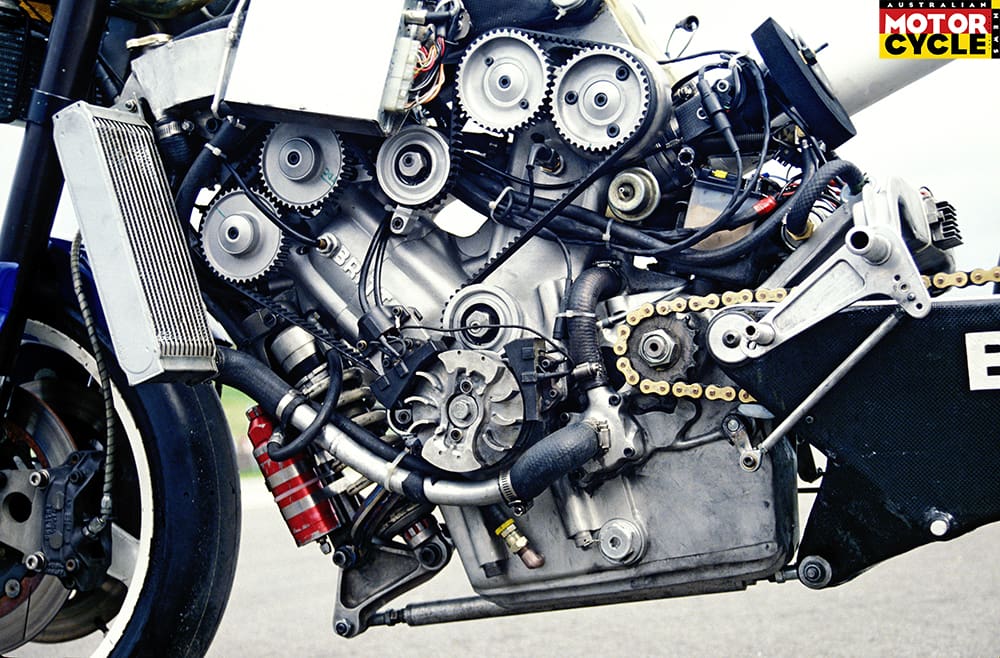

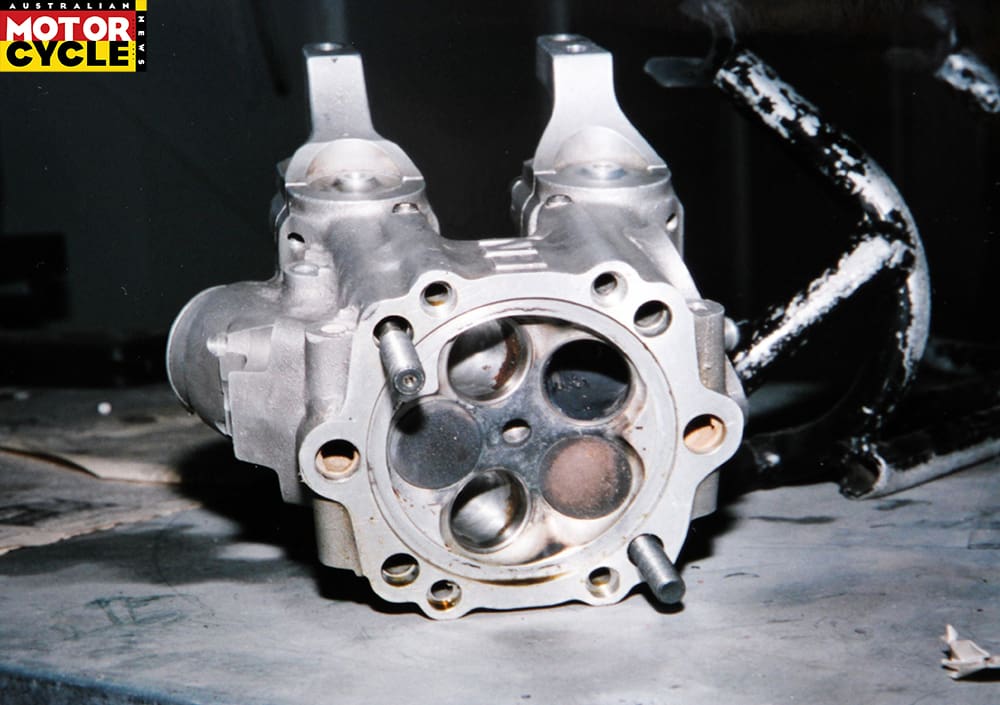

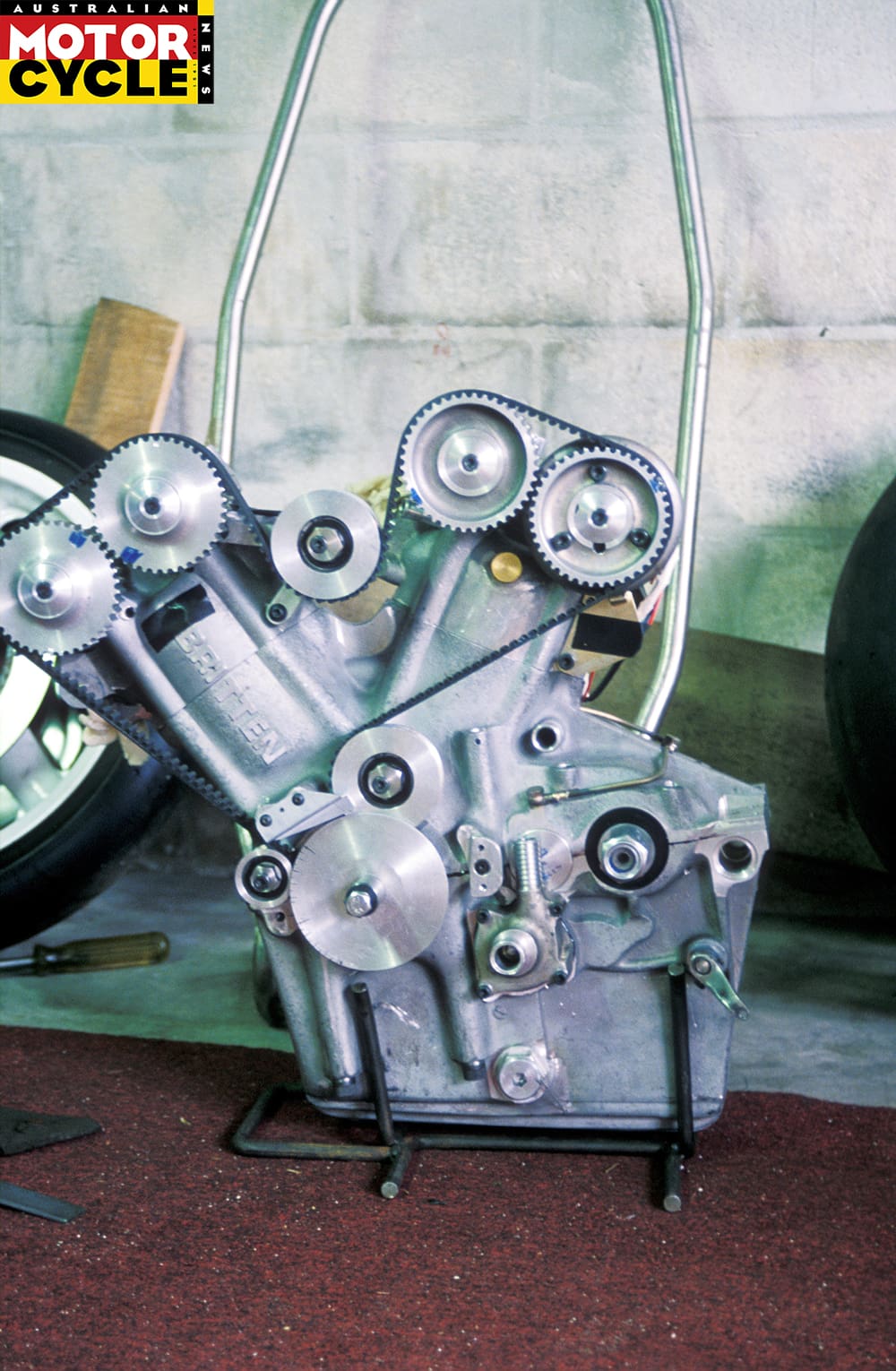

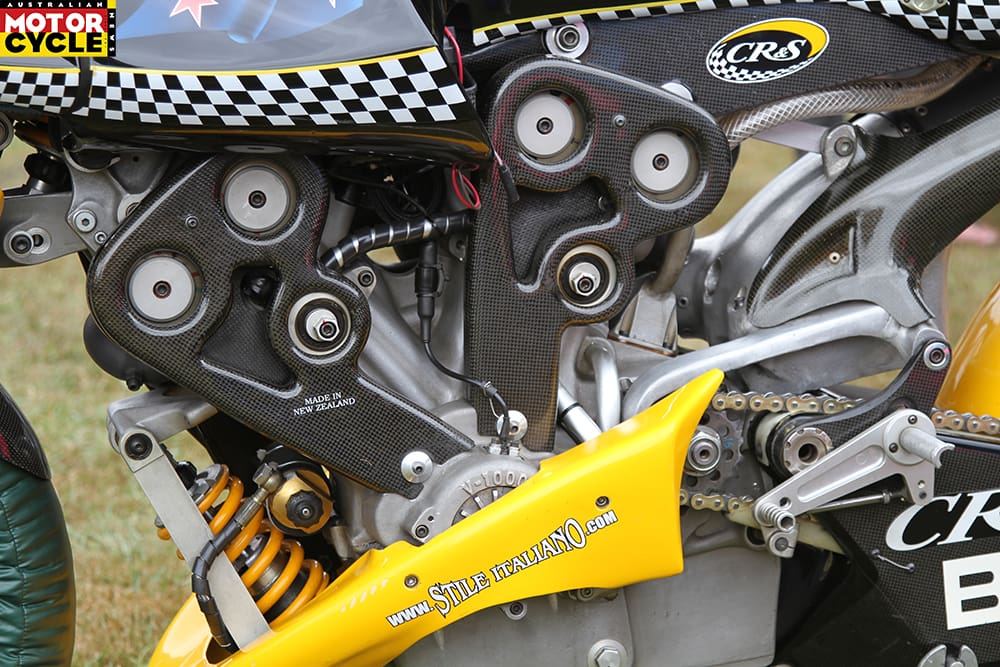

The incredible homemade 60° water-cooled Britten 1000/1100cc powerplant featured fuel injection, but incorporated a five-speed Suzuki GSX1100 gearbox. The standard V-1000 has a 99mm bore x 64mm stroke while the V1100, which has not been used since 1994, uses a 72mm stroke and produced 170hp at 10,500rpm.

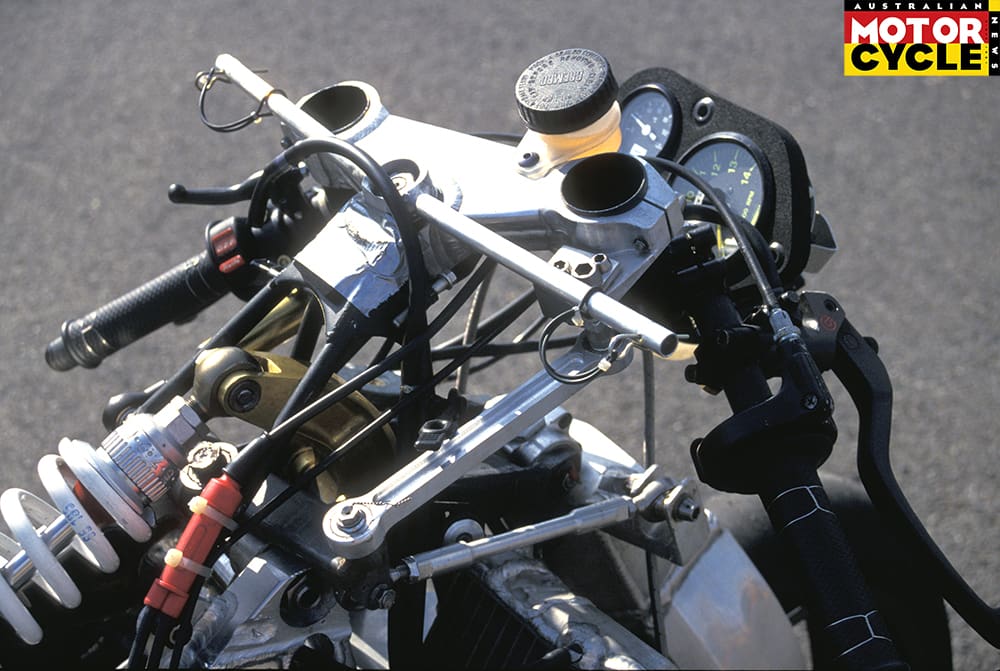

A novel idea was the under-seat radiator, but it was the early engine management system with data logging that helped the team control the V-twin’s output via a red button on the left handlebar. Years ahead of its time, it was enough to attain the fastest top speed during the 1993 Isle of Man Senior TT, and 304km/h during Daytona in 1996.

Several former Britten riders share their battles on Britten machinery with us, not only teaching us more about how they handled, but why the engine’s power was the jewel in the Britten’s crown.

The first

Chris Haldane

In 1988, three-time NZ Superbike champion Chris Haldane was the first person to ride the Britten Precursor, and helped with initial development work.

“The first time we started it, it blew the oil filter off – an oil pressure issue,” Chris recalls, laughing. “The valve was set too high and it just exploded as soon as it started!”

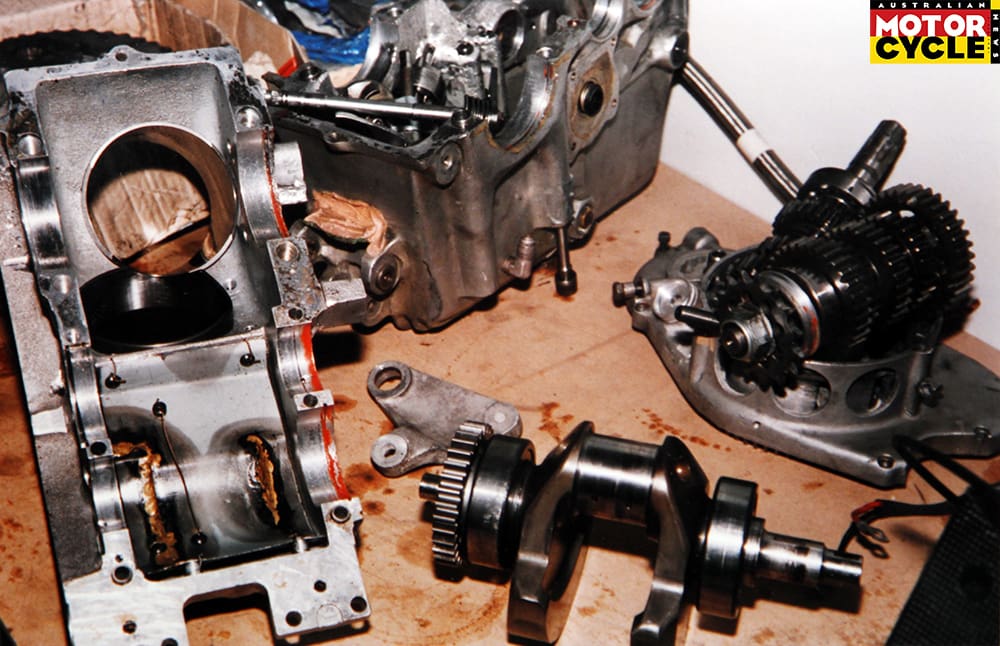

Not surprisingly, the first true Britten powerplant had teething problems such as cylinder bore distortion, pistons or rings issues affecting compression, a sheared a primary gear, clutch issues and continuous cam-belt problems.

“When I ran it in the NZ Superbike championship, it definitely wasn’t the quickest bike but it had a really good spread of power. It wasn’t consistent, the most consistent was when I had it in my own hands between events and John [Britten] wasn’t doing stuff to it! Changing things like cylinder bore clearances or he’d change the manufacturer of different components. He always had a game plan working ahead, he was always moving ahead with development.”

That grunty Precursor engine helped win a wet race.

“At the Sound of Thunder in the rain, I was having a really good dice with Jason McEwen who was riding a Ducati 851. The Britten was solid, it had such good power delivery and really good torque. We raced together until Jason crashed, so I won the race. It wasn’t revving anything like the new-version Britten.

Chris was also the last rider to race a Britten so has the knowledge to compare the two models.

“The fastest I ever rode the new evolution Britten was when we took it overseas – it had an extra 1000rpm. The one I raced in Europe in the ‘Twins’ world series – that was lethal. I think it revved to 13,500rpm. That Britten was number nine, it was brand new when I took it to Japan and Germany.”

Canadian development

Gary Goodfellow

Spanning 18 months, Gary Goodfellow developed the Precursor engine with Colin Dodge in Canada, and in Formula One in the USA. Colin worked for John at the Britten factory and travelled to work at Gary’s Goodfellow Motorsport shop, where they regularly employed Gary’s dyno for considerable engine development.

“I rode the new Britten only yesterday, so I’ve never ridden that bike before,” Goodfellow recently said. “The difference between that bike and the Precursor is the newer bike’s engine is really soft, whereas the Precursor was really aggressive, like in the way of a KTM 1290 [Super Duke] being super aggressive! The whole set-up of the newer bike’s engine is different, it had power all the way through. They are really the same motor, but the upgrade on this one shows that the power has softened.”

The first kiwi to win a world Superbike race and once rated in the top five in world Motocross, Goodfellow used the Precursor’s powerful V-twin engine to win races.

“Yes, for sure! I had more power available than anything else out there – in the AMA F1 class in America I’d be up against Grand Prix bikes. It was pretty good and really strong, I could rev it to 13,000rpm, it just got better and better. As long as it qualified and you could ride it, I could win! I broke the lap record at Westwood and lots of other tracks. The engine was amazing – there was nothing that could keep up with it! It did, like, 180mph (290km/h) at Daytona!”

Secret revs

Jason McEwen

Multi-Britten race winner Jason McEwen loves the engine.

“If you can imagine a pretty hot V-twin, it had plenty of power everywhere, it was like any other race motor because I could rev the date off it! If it’s sucking the air in and giving you the gas and you rev it, it is going to make good horsepower.

“We had a five-valve motor that John built, it was exactly the same as the Britten four-valve engine but with a five-valve head. It had slightly different fuel injection, and that went really well. It had plenty of power everywhere, I could rev the date off it! That was one of the things I helped with, I got them to up the rev range about 1500rpm in the end. It only used to rev to about 11,000rpm. I’ve ridden Ducatis before and I knew it needed to be revved – it was saying to me ‘don’t you change gear yet’.

“John didn’t know about it initially – I had a word with the mechanic and he got on the computer and upped it to 12,000. I went about a second-and-a-half a lap quicker straight away with the extra horsepower. Eventually we put the rev range up to 12,500rpm.”

Exceptional power

Shaun Harris

Shaun Harris first raced a Britten at Donington in 1993 when Ducati world Superbike privateer Carl Fogarty and Harris came onto the back straight side by side. Proving a point Shaun pulled a wheelie all the way down the straight to the surprise of the Englishman.

“He could go nowhere on a bike that he was getting top 10s in world Superbikes on! That’s how fast the Britten motor was compared to everything else.” Harris said, “Its exceptional thing was the power – that’s it.

“It was so damn fast compared to everything else. Yeah, its forte was the motor.”

Drink to that

Paul Lewis

Paul Lewis raced the Britten Precursor in the 1991 US Battle of the Twins at Daytona and qualified on the front row before battling with factory Ducati rider Doug Polen, the 1991 world Superbike champion. During the race, Lewis’s bike began running on only one cylinder in the corners from a loose injector, which probably cost Lewis the race, although he crossed the line a close second to Polen.

A V-twin fan, Lewis was taken by the power of the Britten.

“I’m a massive fan of middle power and ride-ability. I can’t say too much about the Britten because I only did one race, but the middle power was awesome, and that’s what it was all about. [Doug and I] had the same sort of middle power and jump out of the corners, but I probably had four or five miles per hour on him at the top-end.

“It was quite funny at Daytona, because we went across the road to the Holiday Inn, I think there were about 14 of us in the Britten team. John ordered 14 Screaming Orgasm shots, which were topical in the 1990s, and it was happy hour so they gave us 28! So we had 28 shots, got in our hire cars and ran amuck on the beach! I can’t condone that behaviour nowadays.”

Power to weight

Stephen Briggs

Stephen Briggs did well on the international stage.

“There were two Battle of the Twins races at Assen with some local guys on Ducati 916s, down the straight we would just murder them – I’d go past them like they were in the wrong gear,” Briggs recalls. “For the shortcoming around its handling it would make up for it just by pure grunt. If the bike only had, say 145hp, it probably would have struggled against some good Ducatis because I couldn’t rely on the handling – it was probably its achilles heel – but it would make up for it having 165-plus horsepower and weighing 140kg.”

Briggs said the biggest failing of the Britten was its clunky five-speed transmission with a huge ratio jump, particularly on the down-change, when the slipper clutch had to work overtime.

“It wasn’t so bad on the big fast circuits where we used to gear it to use third, fourth and fifth, where the ratios are closer, but in NZ we used first, second and third, which are big jumps. The other thing that was really apparent was how well the injected Ducatis were fuelled. Whereas the Britten was the complete opposite, you really did have to ride it by point and squirt to try to keep your mid-corner speed down. You’d fire it in nice and smooth using the front brakes, turn sharp then fire it back out, because of the shortcoming of the gearbox, but also the fuel delivery which was quite abrupt.

“When I raced it here in NZ, they were concentrating on making more and more power. The compression started to come up, but the more they made the engine fast the more they made it harder to ride. When I went down a gear, now the engine has even more compression – the faster they were making it, the harder it was to ride. But, get the Britten on the right track where it was point and squirt, and use its power to weight ratio, and wow!

“It is a really, really, easy bike to ride fast, but it is actually quite a hard bike to ride slow! That is mostly because the bike has very little effect from crankshaft inertia – the flywheel effect. With a lot of bikes, the higher the rpm goes the harder they are to move from left to right, the Britten doesn’t seem to suffer from that at all. You can get through and you’re still on line whereas if you’re on a bike with a lot of flywheel mass it’s like trying to spin a wheel. That’s one of the Britten’s biggest advantages at a track like Assen where it has high-speed left-rights, so changes direction easy.

“At Assen I did a world Superbike race the weekend directly afterwards on the Muzzy Kawasaki with a factory race engine. Mike Webb (current MotoGP Race Director) and Brent Stephens (ex-Valentino Rossi’s Yamaha mechanic) were the two NZ mechanics. Simon Crafar was on the number-one bike and I was on the ‘B’ bike. I remember when I came in after the first practice and Mike asks excitedly ‘so, what do you think of the power?’ and I said ‘man, this thing feels so slow!’”

World beater

Andrew Stroud

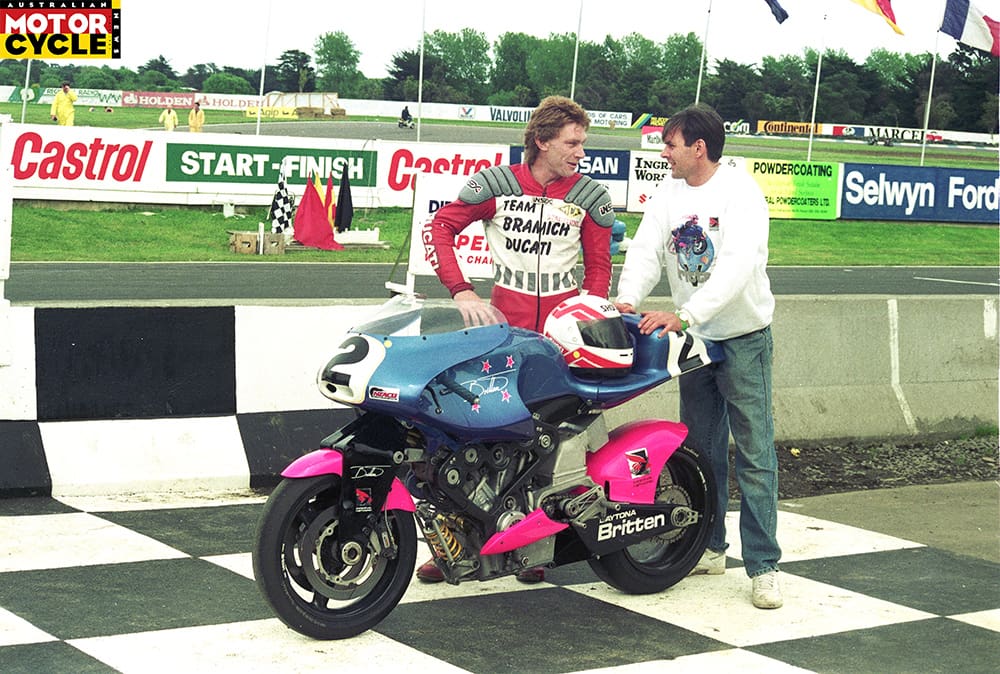

A WorldSBK and Grand Prix rider, Andrew Stroud won the 1995 world BEARS title for Britten, two NZ championships and four years in a row at Daytona Battle of the Twins between 1994 and 1997. He rode most of the 10 different Brittens during the 1990s.

Stroud is perhaps the most famous Britten rider, who’s battery went flat with two laps to go in 1992 while battling for the win at Daytona with factory Ducati mounted Pascale Picotte.

Stroud recalls that Britten international debut: “The first one I rode at Daytona was an 1100, that was the fastest out of all of them. They got a little bit more refined throughout the years, but they were quite similar. Some had a little bit stronger motor than others, or mapped a little better. The ones with the longer strokes had more torque.

“We took the muffler off at Daytona which made it a bit louder but it went faster. The 1000s were a bit more manageable through the infield, just more manoeuvrable, just from the shorter stroke which made it feel like a smaller bike.”

Two years later Stroud took victory in the Daytona Battle of the Twins and BEARS races on that booming 1000cc V-twin powerplant. The big V-twin could be flicked from side to side easier after they removed a massive 5kg off the crankshaft.

“At the first round of the 1999 NZ champs it was faster in a straight line than my Kawasaki which I rode in world Superbikes in 1998. It had good torque, like a tractor! It had lots of low-down power, and the twin created lots more traction than a four-cylinder bike, plus it gripped pretty good.

“It was definitely a good thing to be involved in – the whole project – because it was more than racing any old motorbike. Winning the world BEARS series three weeks before John passed away was the highlight – for what it meant to him in the state he was in. He watched us at Brands Hatch in a world Superbike support race, there were 60,000 spectators and John watched it from his bed, but he was just rapt. It was an amazing achievement really. Most people wouldn’t even attempt to think about starting a project like that, there’s so much involved with it.”

Terry Stevenson Photography Steve Green, Chris de Beer, TS & AMCN Archive