Visitors to the Phillip Island Grand Prix circuit for the Australian MotoGP this year have a treat in store. For now on permanent display in the History of Motorsport Museum at the circuit’s Visitor Centre is a superb collection of GP-winning Italian factory two-stroke racers from Aprilia and Cagiva. The collection was recently acquired by the circuit’s owners, the Fox family, from a private collection in Italy.

The array of nine Cagivas, which between them scored three grand prix victories and 13 podiums, covers the glory years of the Italian marque, during the decade when it became a serious rival to the Japanese manufacturers thanks to the passion of the two Castiglioni brothers, Gianfranco and Claudio.

Push start

The brothers had only one real objective when it all began in 1978 – being there. As bike-mad fans, they had tried to purchase the MV Agusta race team when it pulled out of racing at the end of 1976, but the upstarts were turned down. Count Corrado Agusta preferred to see MV die in peace rather than let a couple of rich kids take over the glorious four-stroke ‘fire engines’.

Undaunted, the Castiglionis bought a Suzuki RG500, painted it in the MV race colours of red and silver, and entered Marco Lucchinelli on it in 1978 – the same year they purchased the old Aermacchi factory beside Lake Varese from Harley-Davidson, and renamed it Cagiva after their father, Castiglioni Giovanni of Varese. But what the brothers really wanted was the Harley-Davidson race shop that had taken Walter Villa to four 250/350 world titles in the previous three years.

For 1980, 500GP world championship runner-up Virginio Ferrari was recruited to ride the Cagiva Cl, with a Bakker frame housing an in-line four-cylinder engine owing more to Yamaha than Cagiva. Ferrari qualified 35th in the final round, proving that the new Italian bike wasn’t as fast as a standard TZ500. Time for a rethink!

So the Bakker frame received an all-new in-line four developed in Varese – the first ‘proper’ Cagiva, now with rotary valves behind the cylinders, driven by a combination of bevel gears and toothed belts – that produced 88kW at 12,000rpm. Ferrari finally qualified for a race at the end of 1980, finishing last in the San Marino GP at Imola. But a genuine 500 Cagiva had finally raced in a grand prix.

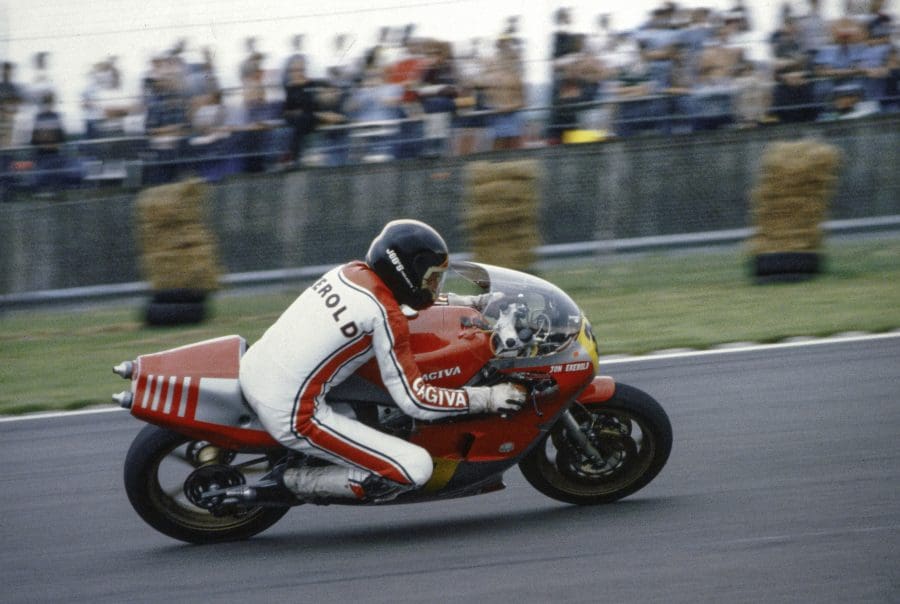

The 1982 C2 was Cagiva’s first rotary-valve square-four racer, unashamedly based on the world champion RG500 Suzuki. Measuring 56 x 50.6mm (like all Cagiva 500GP bikes ever built), the new engine delivered 95kW at 11,600rpm and was easier to ride and faster than the privateer Suzukis and Yamahas filling up GP grids, but had uncertain handling due to its tubular aluminium frame – the first chassis designed in-house at Cagiva. This bike was entrusted to the first of Cagiva’s several foreign riders, South African Jon Ekerold, who as holder of the 350GP title was also the first of several former world champions to join forces with the Castiglionis. Ekerold regularly qualified the C2 and in the final GP of 1982 at Hockenheim he finished 10th to score Cagiva’s first world championship point. Another target achieved.

A rostrum place took a little longer. After failing to convince Ekerold to stay for 1983, Cagiva rehired Ferrari to ride the all-new C7, another rotary-valve square-four. Using electronic powervalves for the first time, they raised power to 99kW at 11,500rpm, but the new tubular aluminium open-cradle chassis using the engine as a stressed member saw weight increase 5kg to 125kg, and handling problems were not resolved by a full-cradle chassis design. Barry Sheene proposed they supply engines for Harris to build him a Cagiva-powered 500GP bike, and this might have been a good move, but the project came to nothing and Ferrari was replaced for 1984 by Marco Lucchinelli.

The marriage with Marco was always going to end in tears, and was hastened by his refusal to start the non-title but high-profile Imola 200 because the organisers wouldn’t meet his request for extra start money – a problem redressed on race day only by the Castiglionis flying the requisite extra lire to the track in their private helicopter.

Endurance world champion Hervé Moineau replaced Marco to race the C9, an updated version of the C7 with an all-new twin-spar deltabox chassis whose potential he demonstrated by finishing a point-scoring 10th in his first GP in Austria. But the Cagiva was the heaviest bike in the class, offsetting the benefits of aerodynamic bodywork developed in the Aermacchi aircraft factory wind tunnel in Varese.

Cagiva followed Yamaha and Honda in moving to V4 engines as the 500GP world began to treat the Italian team with cautious respect. The bikes were fast, but let down by uncertain handling, excess weight and a razor-edge powerband – though 101kW at 11,500rpm was powerful back then.

Encouraged by Kenny Roberts’ assessment that they had the basis of a half-decent bike, the Castiglionis dug deep to fund a completely new engine, a crankcase reed-valve 90º V4 with twin contrarotating crankshafts that Lucchinelli, temporarily back in favour, debuted in 1985.

The C10/V’s engine delivered 104kW at 11,800rpm and had a friendlier power delivery, making it competitive with the 1984 J-bikes – but 12 months later! Cagiva’s perpetual problem of being one step behind Japan Inc. had by now become a way of life, but with rising Spanish star Juan Garriga aboard, the new Cagiva C10/V at last began to get on terms with the Japanese factory bikes, kicking off with an eighth place finish in the opening 1986 GP on Garriga’s home ground in Spain.

In Juan’s hands the Cagiva became a regular

top-10 contender, and Kenny Roberts’ supposedly secret two-day test at Misano (which was front page news in Italy), resulted in his confirming that the C10/V had real potential. Cagiva was on its way.

Growing pains

Garriga returned to the 250 class for 1987, but his performance with the C10/V encouraged Cagiva to persuade Mikuni to supply the same dual-body carbs fitted to the world champion Yamaha V4s, enabling a much more compact 56º V4, which duly appeared at Monza in May 1987. The Castiglionis also restructured the team more professionally, now with two riders – Raymond Roche and Didier de Radiguès – a sponsor (Bastos cigarettes from Belgium) and an external team manager (future WSBK guru Francis Batta) in charge of everything.

Cagiva became a genuine contender and Didier placed fourth in the penultimate GP in Brazil, just 10 seconds away from that first rostrum finish. The pace of development now surpassed that of Japan Inc., with the Varese R&D team responsible only for technical development, and Batta’s Belgian-based operation running the race effort. With 114kW at the gearbox at 11,800rpm, the now reliable and potent V587 seemed poised for success.

Sadly, it wasn’t to be. The Castiglionis were never happy with their bikes being based elsewhere, and especially not plastered with large cigarette sponsorship stickers, so they aborted the Batta deal in favour of a new one-bike team run from Varese for Randy Mamola. This promised to give Cagiva a shot at the top at last, but a disastrous gamble on using Pirelli tyres, with handsome sponsorship to replace the fag money, negated any chance of this. Pirelli was new to modern-day road racing, so Cagiva’s momentum was stymied. Still, a wet Spa race allowed rainman Randy to achieve another of the brothers’ targets, a rostrum finish, which earned him a Ferrari Testarossa as reward!

Fourth place in the next, dry GP in Yugoslavia and sixth the following race in France seemed to confirm that Cagiva and Pirelli had finally cracked it, but that was as good as it got.

For 1989 Cagiva returned to Michelin, but the season wasn’t a success, despite an extra 2.2kW from an engine with an included cylinder angle opened up to 70º for more reed valve area and better airflow to the carbs. But while scaling a reasonably competitive 125kg against the V4 Suzuki’s 115kg, the ’89 Cagiva had severe handling problems caused by a radical weight distribution of 60/40, which didn’t help a bike that also had traction difficulties owing to a flawed rear suspension design.

So 1989 was mostly a write-off, with Mamola finishing only 17th. The V589 engine also had a very narrow usable powerband; while the Japanese V4s could run as low as 7000rpm and had 1000rpm of overrev beyond their absolute power peak, the Cagiva came on strong at 10,000 rpm and was all done at 12,200 rpm – with zero overrev.

Despite a three-man team including Cagiva’s investment for the future, Alex Barros, and the best GP test rider in the world, Ron Haslam, Cagiva floundered in 1990. Haslam was hurt early on, Barros was brave but totally inexperienced in 500GP development, and Mamola had simply lost interest. When a wheelie on the warm-up lap at Assen went horribly wrong and Randy flipped backwards, his days at Cagiva were numbered.

From being true contenders in ’87, Cagiva was again reduced to making up the numbers and, despite the mid-season appearance of an exquisite new bike with a carbon-fibre chassis developed with Ferrari, the Castiglionis were ready to throw in the towel. Yet, with 121kW at 12,200rpm, and with a little overrev at last, better low-down power delivery and improved handling from more rational chassis geometry, the Cagiva had all the makings of a contender. It only needed a rider the team could believe in, who also believed in the bike.

Glory days

That man was four-time world champion Eddie Lawson. After an off-season test he signed a two-year contract for 1991/92, with Barros as understudy. Without this, the Castiglionis would surely have retired hurt to concentrate on superbike racing, where their other brand, Ducati, had just become world champion.

Instead, history records that Lawson totally revitalised Cagiva. The Varese race shop accelerated development with the arrival of Ferrari F1 engineer Riccardo Rosa, and Lawson soon secured three more 500GP firsts in the 1991 Italian GP at Misano: qualifying a Cagiva on the front row; leading a race for the first time (in front of an ecstatic crowd); and a rostrum finish in the dry. The last of these feats was repeated at the French GP at Paul Ricard, where the Italian bike’s superior top speed helped Eddie win a race-long duel with Kevin Schwantz’s Suzuki for third. Seventh in the points at season’s end was their reward.

With a bike right on the new 130kg weight limit and 126kW at 12,000rpm on tap, the V591 Cagiva – now with a wider 80º angle between the cylinders – was truly on the pace, and matched the Japanese for technical sophistication. With programmable digital ignition, there was 15 per cent more power at 8000rpm than before and for the first time a usable overrev of 12,800 rpm – all key factors in exploiting the engine’s potential. And under Lawson’s urging, chassis designer Romano Albesiano (now in charge of Aprilia’s MotoGP team) had produced an all-new frame in just four days that gave more stable, measured handling via Öhlins suspension.

Finally, the Cagiva was a potential race-winner, and in 1992 that hope became reality. After Honda had reminded them of a similar idea they’d had years before with the square-four C9 engine, Cagiva introduced its own version of the ‘big bang’ engine at Assen in June, and immediately passed another milestone when Lawson put a Cagiva on pole.

It took only until the next race for a modern two-wheeled fairytale to come true on 12 July 1992 when, in a brave and tactically brilliant display of wet-weather riding on a drying track, Eddie Lawson won the Hungarian GP to give Cagiva its first road racing grand prix victory in 12 years of trying.

This achievement was as much applauded in the race shops of Cagiva’s rivals in Hamamatsu and Suzuka as it was back home in Varese. The Japanese factories welcomed Cagiva’s emergence as a valid European contender – just as Ducati is in MotoGP today. Its success represented an overdue reward for the billions of lire, millions of man-hours and immeasurable enthusiasm poured into the project by the Castiglionis.

But there were more chapters to be written, for the 80º V592 Bombardone (literally ‘big bang’) now delivered 130kW at 11,900 rpm, and under Rosa’s direction the team was outstripping all but one of its Japanese rivals in the pace of development: Cagiva was the first to adopt an electronic speed-shifter on a 500GP bike; experimented with semi-active suspension; varied the total firing angle to suit different circuits; worked on an early electronic traction control system; and in conjunction with TAG-McLaren evolved an increasingly effective direct electronic fuel injection system.

The Cagiva now used an electronic throttle sensor on the outer end of the trick 36mm Mikuni carbs to link with the tacho reading to operate the cylindrical exhaust powervalve, and the Kokkusan ignition was not only base-tuned with an EPROM chip but was then also linked to the operation of the power valve and carburation powerjet, as well as the gear selected – there was even a different ignition curve for each of the six ratios in the cassette-type gearbox.

Such examples of technical and electronic sophistication on the Cagiva underline the way the Italian team had climbed to the highest level of technical evolution, overtaking some of their Japanese rivals on the way.

When Lawson retired from GP racing, he was replaced by fellow American Doug Chandler, who immediately showed how competitive the V593 was out of the box by leading the opening 1993 GP in Australia, before finishing a strong third.

Equipped again with Öhlins suspension, the Lady in Red seemed set for the top – but Chandler was injured in the second race in Malaysia and his novice teammate, Mat Mladin, struggled to learn the 500GP ropes. Still, with 133kW at a revvy 12,700rpm, the Cagiva was now a potent device, breathing through huge 39mm Mikuni carbs – a lot bigger than anything else in 500GP racing. Despite this, it was almost as tractable as a superbike low down, yet had heaps of overrev up high, with a slight lack of acceleration its only weak point. Much of this improved top-end performance was due to new carbon-fibre intake ducts developed in the Pininfarina wind tunnel. The twin-spar chassis was further refined, and now fitted with a Ferrari-made carbon-composite swingarm.

Yet all this good work looked set to be wasted, until team manager Giacomo Agostini signed brilliant but wayward ex-250GP world champion John Kocinski for the last four races of the season, after the American split from Suzuki’s 250GP team.

Kocinski was the shot in the arm Cagiva needed. After placing fourth in his first two races while getting the bike set up how he wanted, Li’l John took victory on home ground at Laguna Seca in his third race for Cagiva. He almost repeated that victory in the final race of 1993 at Jarama, but Itoh crashed his Honda right in front of him, bringing him down. Cagiva had made it to the top of the pile, though – the one-time Italian no-hoper was now the bike the Japanese teams had to beat.

An all-new composite chassis was adopted in 1994, combining carbon spars with an aluminium steering head and swingarm pivot to create a very stiff but light and readily adjustable package. The V594 engine was further refined, with different variations on the big bang theme, and now delivered 134kW at 12,600rpm – enough to make Kocinski a season-long contender.

As runaway victor of the opening GP in Australia, followed by second in Malaysia, Kocinski went to Suzuka leading the world championship. After five more podium visits, he finished what would be his (and Cagiva’s) final year in GP racing in third place overall, just two points behind runner-up Luca Cadalora on a Yamaha.

Cagiva’s final chapter

Sadly, just as Cagiva had reached the peak of GP racing, troubles elsewhere in the Castiglionis’ empire drained them of the cash to go racing, and a journey that had begun in Germany in 1980 ended in Italy in 1995, when it was left to Frankie Chili, the charismatic matinée idol crowd-pleaser, to provide Cagiva’s GP swansong. He entered the V594 as a wildcard at the 1995 Italian GP at Mugello, qualifying on the front row in third place and winding up 10th in the race.

The curtain then fell on this Italian two-wheeled soap opera. In the course of 15 years, the 500GP Cagivas scored three victories (all by American riders), 11 podium finishes, six pole positions and three fastest laps.

Was this a fair return on the investment made by the Castiglionis during that period? Probably not. But Cagiva left an indelible mark, and its bikes remain arguably the most beautiful racing motorcycles ever to have graced the racetrack.

And another thing is for sure: Cagiva’s hard-earned success, obtained in the face of scorn and derision from many 500GP insiders, was a reward for innovation, determination and passion.

Dreams can come true!

Words ALAN CATHCART

Pics ALAN CATHCART ARCHIVES