Two 1950s thrill seekers went on the world’s first corporate-sponsored global adventure

BMW provided two of its then-new R1150 GS bikes, which became a bestseller for the German company after the ratings-winning, seven- episode TV series Long Way Round was released in 2005.

But Ewen and Charley weren’t the first ‘corporate adventure riders’, whose efforts boosted sales of a particular model motorcycle. That honour falls on Italians Leopoldo Tartarini and Giorgio Monetti who, 60 years ago, rode across 42 countries and five continents to promote Ducati’s new 175 Tourismo model.

Like Ewen and Charley, they filmed their epic adventure, but on 16mm cameras with no sound. Now, belatedly, a film and book are finally being released.

Like Ewen and Charley, Leopoldo and Giorgio had factory support (from Ducati), professional assistance in planning their route and a list of dealers in some of the countries they travelled through if they needed help. Unlike Ewen and Charley, they rode without backup vehicles, did their own filming, took a year and covered over 60,000km, not four months and 30,000km.

This is their story.

AT FIRST GLANCE Leopoldo Tartarini and Giorgio Monetti appear to be polar opposites. Tartarini was a popular Ducati works racer, forced into premature retirement with a serious leg injury that had left him with a limp. Born into a Bologna motorcycling family, he had first ridden a minibike-sidecar outfit built by his father when he was just four years old. During World War II Tartarini combined his schooling with working as a mechanic at his father’s business. When his father died in a motorcycle race after the war, Tartarini took over the business.

Monetti was from one of Bologna’s wealthiest families that dictated its sons qualified either in medicine or law. He chose law but really had a passion for the countryside and travel. While Tartarini was taking over his father’s business, Monetti was taking extended breaks from his study to tour Europe on a variety of motorcycles, including a heavyweight Matchless 500cc single, a tiny NSU 100cc two-stroke and even a Gilera Saturno sports bike.

Meanwhile, Tartarini was balancing running the family’s motorcycle business with racing, especially in the new endurance events run along the length of Italy’s rebuilt post-war road system.

He first came to national prominence by winning his class in the 1200km-long Milano- Taranto race on a homebuilt BSA 650cc-powered sidecar. He then won the first Moto Giro d’Italia in 1953, covering over 3000km on his privately- owned Benelli. Tartarini was quickly elevated

to works-rider status, first with Benelli and then Ducati. A high-speed crash down a bank in the 1956 Moto Giro forced him to quit racing, and there were even fears he wouldn’t walk again. Monetti also developed a passion for speed, but on four wheels. He took part in circuit racing and hillclimbs in a series of Fiats that he modified himself. Later in life he would help Ducati’s legendary engineer Fabio Taglioni design and develop the 1.5-litre V8 F1 motor (which he still owns!). Monetti also built the first proof-of- concept turbo engine for Fiat. He is now long retired to a farm outside Bologna.

Tartarini’s later efforts were even more spectacular. He established the Italjet motorcycle company in 1960 and also worked as a consultant for Ducati, most famously on the green-frame Ducati 750SS race replica of 1973. He passed away, aged 83, in 2015.

The two adventurers became united after Tartarini suggested to Ducati management that he could promote the new 175 Monoalbero by riding it from Italy to Turkey, or perhaps as far as Africa. Ducati’s free-thinking managing director, Giuseppe Montano, countered with an even more audacious plan: ride this untried new model around the world. Montano, who at the time was transforming Ducati into one of the world’s major motorcycle companies, wasn’t afraid to take a risk. With Ducati agreeing to underwrite what was the world’s first corporate motorcycle adventure, Tartarini needed someone to ride shotgun. Monetti, with both his legal and mechanical skills, fitted the bill perfectly.

WHY A 175 MONOALBERO?

Back in the 1950s most Italian motorcycle companies produced road models based on their lightweight long-distance endurance racers, seen in such events as the Milano Taranto and Moto Giro d’Italia.

Ducati dominated many of these events from 1955 until 1957, thanks to their brilliant designer Fabio Taglioni. But by the late-1950s, as Ducati grew as a factory and pushed into export markets, it also needed a larger road-only model to challenge the established European, English and American manufacturers.

Taglioni had designed and produced Ducati’s first overhead-camshaft single in 1954. The 100 Gran Sport appeared on the racetrack and soon proved unbeatable in its class. It would shape the company’s future over the next four decades.

The strength of the original bevel-driven, single- overhead-camshaft design was proved by it being enlarged from the original 98cc all the way up to 436cc in the late 1960s. Versions of this classic single-cylinder engine remained in production until 1982 via Spanish affiliate Mototrans.

While Ducati developed twin-cam and even three-cam racers, it released the road-going 175cc Monoalbero (meaning ‘single camshaft’) at the Milan Show in November 1956. This was the company’s first production model offered with a SOHC engine.

The first version to reach the market in early 1957 was the 175T Tourismo. Ducati, well-known for selling its performance models to local café racers, was aiming for a new market, the touring rider. The 175T was soon followed by Sport and Formula 3 variants, and even what could be considered an early custom bike, the Americano. Aimed at Ducati’s new American market, this featured a studded saddle, cowhorn handlebars, dual air horns and flashy finishing details.

Despite being designed as a road model, the Monoalbero engine was very sophisticated in a decade when most motorcycles had a long-stroke configuration with pushrods driving overhead valves, cast-iron cylinders, chain primary drive and dry-sump lubrication. The Ducati had a bore/ stroke ratio of 62mm/57.8mm. Its SOHC was driven by bevel shafts and gears. The aluminium cylinder, slanted forward 10 degrees, had a cast- iron liner. Geared primary drive was mated to a four-speed gearbox. Lubrication was an automotive-type wet-sump system driven by a geared pump. In its ultimate Super Sport form, the Monoalbero produced 14bhp (10.4kW) at 8000rpm with a top speed of 135km/h.

By contrast, the Tourismo model produced 11bhp (8.2kW) at 7500rpm but with a dry weight of 102kg, it could nudge 115km/h and had a highway cruising speed of 90km/h. It was a near- perfect combination of light weight and engine performance that could challenge England’s 500cc pushrod singles and twins, and BMW’s 500cc flat-twin road models, not to mention Harley- Davidson’s big V-twins.

Ducati was now on the world map and on the path to sales success. All it needed to complete its marketing publicity was some heroic achievement to confirm the 175T’s durability.

Enter Leopoldo Tartarini and Giorgio Monetti.

The Journey

Tartarini and Monetti, under the sponsorship of Ducati, relied on experts to plan their 1957-8 world tour. One of Italy’s oldest tourist agencies, Viaggi Salvadori, mapped out a route that took in as many countries as possible that either had Ducati distributors or showed potential to become new markets.

Meanwhile Ducati factory technicians gave both motorcycles a thorough going over. Mechanically they were left standard but rear subframes were revised to incorporate solo seats and luggage racks that carried special aluminium cases and a spare wheel. Braced handlebars were fitted, along with crash-bars. The riders were given detailed maintenance instructions, including how to undertake complete engine rebuilds if they had to.

They also were kitted out in leather riding suits and given handguns for personal protection.

Possibly becoming the pioneers of adventuring riding sponsorship, the travellers secured assistance from Regina chains and Pirelli tyres, and cash from other benefactors.

Their farewell from Ducati’s factory carpark on 30 September, 1957, was blessed by Cardinal Giacomo Lercaro and over 1000 assembly workers, motorcycle club riders and Tartarini’s race fans. Soon they were on their own and heading to their first big test.

The world was undergoing huge political change in the 1950s. Many nations were in the process of throwing off the shackles of European colonial rule. Others were tearing themselves apart as populations revolted against corrupt regimes.

Although just a day’s ride east of Italy, Yugoslavia was a world away for wide-eyed Tartarini and Monetti. Under President Marshal Tito, this conglomeration of six socialist republics was on a course of non-alignment with either Russia or the West while it expanded its manufacturing exports. The economy was growing but it was still largely a closed society with a feared secret police force.

For the two weeks it took Tartarini and Monetti to travel south towards Greece they were shadowed by a man in a raincoat and grubby white nylon shirt. Our intrepid riders also soon realised that a long jail sentence awaited anyone caught with armaments, so they flushed their pistols down a toilet.

In Greece they soon realised that lack of petrol would become a constant problem. Even with extra cans tied to their luggage they frequently ran out, and had to pour the last amount into one bike and tow the other with a hand on the rider’s shoulder.

Like most explorers, Tartarini and Monetti soon modified their load. Heavy spare parts, such as pistons and conrods, were left at local Ducati dealers, while the large expedition luggage cases were replaced with featherweight cardboard suitcases. Their bulky leather riding suits were often shunned for T-shirts and cotton trousers.

“Impoverished immigrant style,” was the description the riders gave to their new image. They passed through Turkey, Lebanon and through Iraq and Iran towards Pakistan and India.

Just a few months earlier a populist uprising had overthrown Iraq’s British- supported monarchy. As Tartarini and Monetti rode into Baghdad they noticed four people recently hanged under a colonnade. The vast deserts they now crossed also brought enduring memories.

Monetti said later the flat horizon where the blue sky met yellow sands brought him “a sense of claustrophobia” that he found “wonderful” and only matched later by a similar feeling in the Andes mountains of South America. Tartarini said he remembered “survival problems to find food and water”.

The pair also began to discover that a simple trust of strangers and showing a non-judgmental attitude would be repaid by kindness and honesty, and only on a few occasions did they feel threatened.

THE ADVENTURE

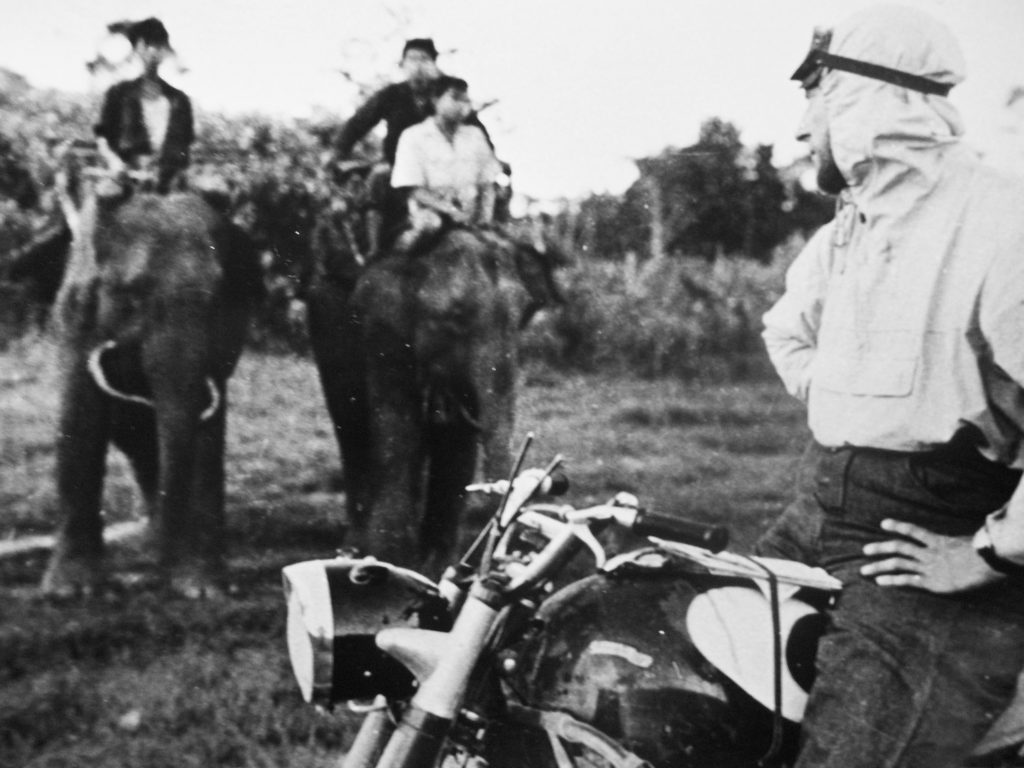

As the adventure unfolded one amazing experience followed another. Sharing a highway in India with elephants being used as beasts of burden, bullock carts, naked holy men and sacred cows was one. Another was repairing 30 punctures on badly rutted roads.

They rode through Burma and Thailand and headed down to opulent Singapore, which even had a Ducati showroom. Opting to stay in the more affordable waterfront region found the adventurers caught up in a bar-room brawl and rescued by visiting Italian sailors.

More serious problems arose when Tartarini and Monetti entered Indonesia, which was still in the throes of establishing a peaceful self-rule after kicking out the Dutch. The two riders, especially the blonde Monetti, were mistakenly identified

by many locals as Dutch, so authorities detained them for their own safety. After a couple of weeks President Sukarno released the pair, treated them to a lunch with his ministers and sent an escort from his newly-formed police force to accompany them out of the country.

Next stop was Darwin, Australia, to start 1958. The riders described the Top End as looking like

a “wasteland” after the lush tropical islands. The Northern Territory’s capital was a tiny town of basic timber buildings, not the prosperous city it is now. And the food wasn’t much better.

A misunderstanding in a restaurant resulted in another punch-up before the pair headed down to Melbourne. There they visited the Italian Consulate General’s office, where Monetti met the great man’s daughter, whom he would eventually marry (they are long amicably separated).

Next stop was the Americas. Rather than traverse the United States, the journey passed through one of the engineering marvels of the modern world, the Panama Canal. Panama City, the country’s capital, also had a Ducati dealership.

Then it was on to Venezuela in March, 1958, a country still simmering with internal tensions after January’s coup d’état.

The riders rested up at a couple of idyllic locations. Two incidents summed up a lot about these adventurers and their attitudes to travel.

The practical joke: A local journalist on the island nation of Curacao, just off the coast of Venezuela, came to interview Monetti. His wandering hands revealed very clearly what he wanted. With great diplomacy Monetti said: “I can’t accept but my friend is very talented,” ushering him to Tartarini’s room. He then waited outside suppressing his laughter before the sound of a scuffle was heard, followed by the journalist’s hasty departure.

The package from home: A package was waiting when they arrived at their hotel on Isla Margarita, a popular Venezuela holiday island. Tartarini’s sister, Fiorella, had sent news from home and a recording of the new hit song Volare, sung by Italian master crooner Domenico Modugno. Tartarini was so excited he insisted the hotel replace their lobby music with Volare. Later Monetti would say: “I wasn’t impressed by this episode. Volare didn’t move me a lot. Poldino (Tartarini’s nickname) missed Italy and tagliatelle. I didn’t miss home.”

Back on the road in April, 1958, the journey hit unimagined challenges on the Pan American Highway south of Ecuador. Mud and slush reduced daily distances to just 20km.

Then they had to cross the Andes, including the 3500m-high Paso del Cristo Redentor pass. When the bikes failed at high altitude they had to take refuge in a tunnel to escape hypothermia, and then coast with engines off down to the Mendoza region of Argentine. There they undertook repairs.

“Today you throw away an engine and fit a new one,” says Monetti. “Back then you even fixed your motorcycle in the street.”

It took until June for the pair to make it into Brazil. When they got to Sao Paulo, authorities suggested they spend 10 days off the bikes visiting one of the last traditional tribes living in the Mato Grosso. It left a lasting impression on Monetti, concerned about the changing world and the future it offered.

“Authorities gave us a carbine and said that if we had any problems, shoot them,” he remembers. “As if we had a licence to kill.” He was equally unimpressed with the missionaries trying to put an end to the indigenous way of life.

“The local tribespeople received us with indifference and after I met a missionary I took the liberty of telling him that maybe he was pestering them instead of bringing the faith, because he was teaching something to somebody who maybe did well, even without knowing it.”

The original plan had been to travel by ship to Cape Town and ride up Africa’s east coast but political unrest in many of those countries found the pair in Dakar, Senegal. Ironically, they followed a large part of the much later and famous Paris-Dakar rally route. But it wasn’t a challenge to these seasoned adventurers.

“We felt like we were almost home,” says Monetti, who described the distance from Dakar to Europe as “one finger’s length” on the world map the pair had. The Sahara was just another desert to cross.

TRIUMPHANT HOMECOMING

September 5, 1958 was a clear, sunny day in Bologna. In the late afternoon a loud hum from a huge fleet of motorcycles drowned out the normal traffic noise on the city’s main road, the Via Rizzoli. Tartarini and Monetti were on the last few kilometres of their odyssey and heading back to the factory they had left nearly a year earlier, surrounded by fellow Ducati riders.

A few days earlier a message had gone out to all Ducati factory workers: “All employees in possession of light single-camshaft Ducati motorbikes have to come to the factory with their bikes… The employees will escort the two globetrotters from Bologna’s Ducati dealer to the factory’s entrance… It’s the director’s desire that this event takes place with the usual given discipline, that doesn’t mean to limit enthusiasm, but to highlight it.”

Waiting at the factory gates with most of its workers was the proud managing director, Giuseppe Montano. He spoke from the heart when he told Tartarini and Monetti: “We were with you in the wilds of the forests and in the deserts, we heard the nocturnal crackle of the machine guns with you in Syria and Indonesia, the screams of revolt in Venezuela… and now you are here, like two warriors who have won a peaceful battle and I know what you are feeling today. As all those do, who on long journeys tempt their fate or who leave their homes for war or necessity, return with souls matured.”

And so Montano summed up not only Tartarini and Monetti’s global circumnavigation but the feeling everyone who undertakes a major motorcycle journey experience, as well as the family and friends who remain at home.

WORDS HAMISH COOPER

PHOGRAPHY PHIL AYNSLEY & GIORGIO MONETTI ARCHIVE