Fancy a ride around the fabulous road circuit that hosted the Australian Grand Prix and the Australian TT in the 1930s? It’s still there, and less than three hours from Sydney

Between them, the New South Wales provincial towns of Goulburn and Bathurst had a firm grip on the major motorcycle race meetings when the sport was in its infancy. But Bathurst managed to get the upper hand when the Auto Cycle Union of NSW gained the use of a series of public roads on which to stage the NSW Grand Prix over Easter in 1931.

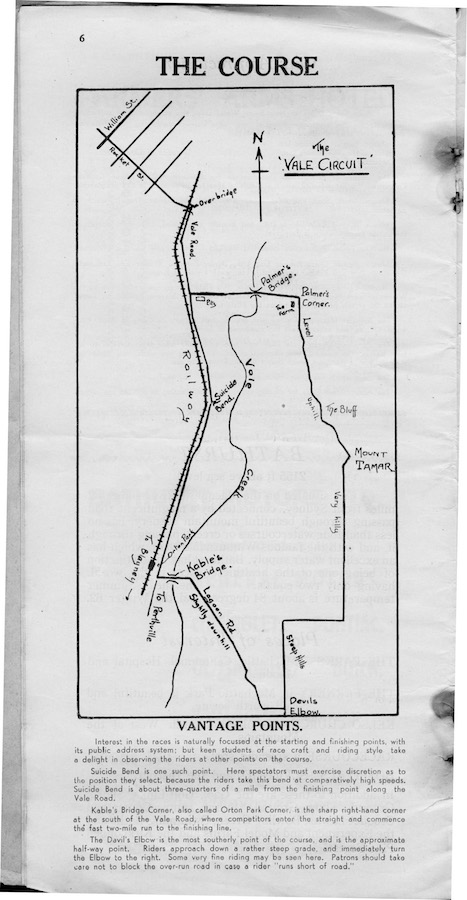

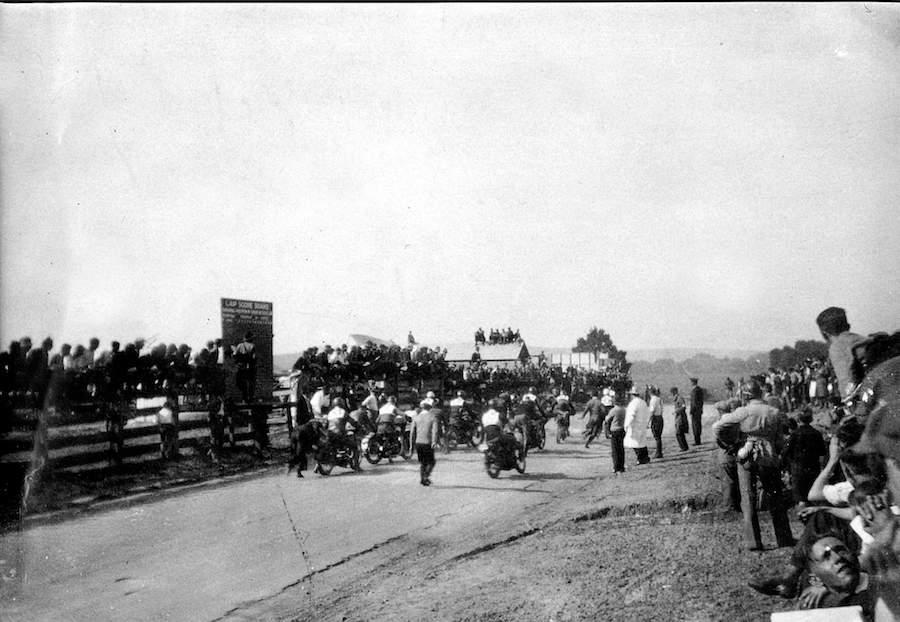

After considering three different layouts, the final decision was The Vale Circuit, located between Bathurst and Perthville. The circuit utilised the hilly terrain around Mount Tamar, crossing Vale Creek at two points via timber bridges. The start/finish area was situated on the main Bathurst to Goulburn road, a busy local traffic route and, not surprisingly, Abercrombie Shire Council refused to allow the busy road to be completely closed.

The solution was to rope off one half of the road, with local traffic guided through by a motorcycle-mounted marshal while racing continued on the other side. It was hardly a satisfactory solution, but it was the only arrangement that could be reached to allow the event to proceed. In later years, an earth bank was bulldozed into place to separate the racing from traffic.

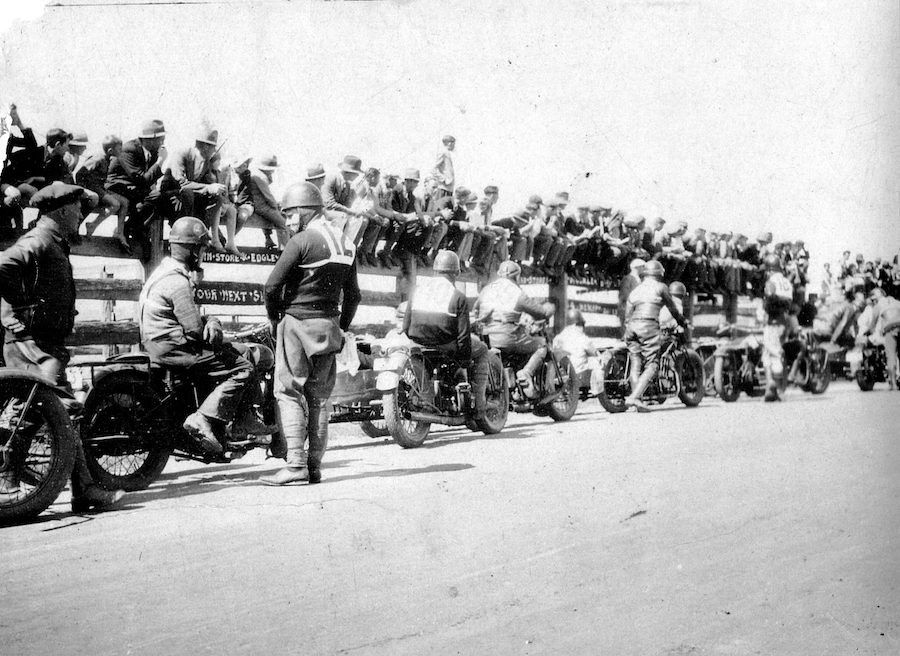

The 7.23-mile (11.5km) circuit was entirely gravel, with the exception of a 100-metre strip of bitumen at the starting point, opposite the Bathurst Sale Yards (which were closed in 2006).

This apparent concession to luxury was no sop to the competitors, though; it was to

permit animal manure to be hosed and swept off the area during sale times. Nevertheless it provided a civilised area for the push-start races to get underway.

A colourful description of the circuit comes from the official program: Interest in the races is naturally focussed at the starting and finishing points, with its public address system; but keen students of race craft and riding style take a delight in observing riders at other parts of the course. Suicide Bend is one such point. Here spectators must exercise discretion as to the position they select, because the riders take this bend at comparatively high speeds. Suicide Bend is about three quarters of a mile from the finishing point along the Vale Road. Kable’s Corner, also called Orton Park Corner, is the sharp right-hand corner at the south of the Vale Road, where competitors enter the straight and commence the fast two-mile run to the finishing line. The Devil’s Elbow is the most southerly point of the course, and is the approximate half-way point. Riders approach down a rather steep grade and immediately turn the Elbow to the right. Some very fine riding may be seen here. Patrons should take care not to block the over-run road in case a rider ‘runs short of road’.

This description is of the circuit in its post-1934 form, when the direction of racing was changed from anti-clockwise to clockwise, because the riders were virtually blinded by the setting sun when heading west along the main straight in the afternoon events.

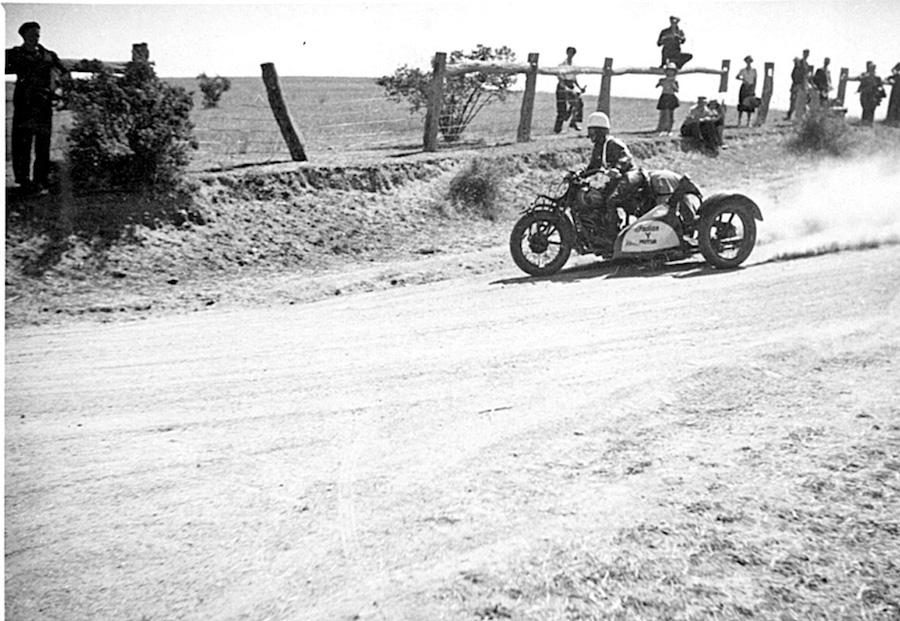

The Vale circuit events, held from 1931 to 1937, attracted the cream of the state’s competitors annually (with the occasional visit from an interstater), but conditions were harsh. The corrugated surface made for a nightmare ride, but dust was the biggest hazard.

The very first meeting, titled the NSW Grand Prix, was held on Easter Saturday, 4 April 1931, attracting an entry of 40 riders.

First event away was the Junior GP over 14 laps, or 162km, with Don Bain the winner riding an OHC 350 Velocette. Bain also led the Senior until he crashed and was unable to continue, letting speedway star and long-distance record breaker Gus Clifton on a Rudge through to win, in a race time approaching two hours.

Wally James, mounted on a twin-cylinder water-cooled Scott two-stroke, triumphed in the Unlimited TT, which was held as a handicap at the Vale meetings, producing an interesting variety of winners. James also set the fastest lap of the day at an average of 96.56 km/h.

For 1932, entries swelled to 52, including four from Victoria and one from Queensland. Victorian star Jimmie Pringle, probably Australia’s top rider at the time, became the first interstate winner when he took out the Senior event on a 490cc OHC Norton.

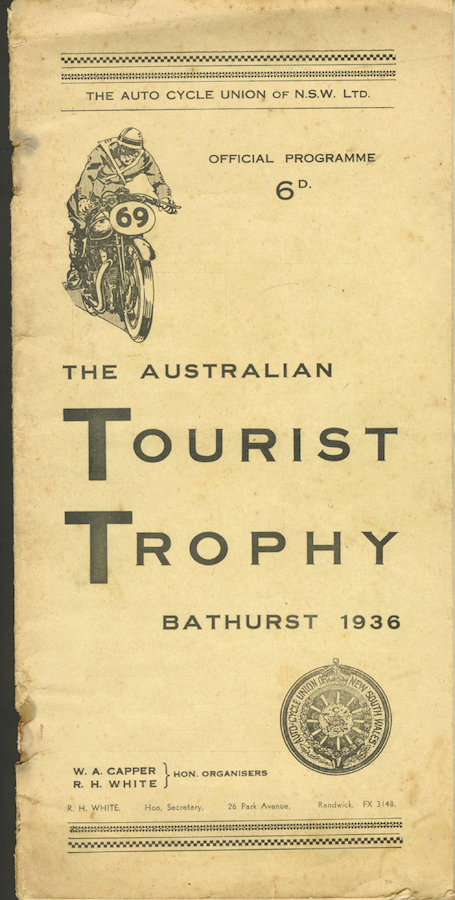

As a sign of its growing stature, the 1933 event was awarded the title of Australian Grand Prix, which, although important, did not have the status of the Australian Tourist Trophy, which came the following year.

Nevertheless, the Grand Prix attracted several big-name Victorians, notably Rudge stars George Hannaford and Norm Osborne (who rode under the pseudonym of Reg East). Once again, Don Bain ran away with the Junior event, and he again failed to annex the main Senior title, this time giving best to Hannaford’s ex-works Rudge.

With the official Australian Championship event, the Australian TT, awarded to NSW for 1934, the only suitable venue was the Vale Circuit, and the biggest-ever influx of interstate riders turned up. A 250cc race was added to the program – run in conjunction with the Junior event but attracting only five entries. Ever-unlucky Art Senior finally persuaded his AJS to last the distance and came home a popular winner in the Junior. To the horror of the partisan NSW crowd, Queenslander Curley Anderson and Victorian Jimmy Pringle took the first two places in the Senior.

The perennial menace of choking dust was absent in 1935, replaced by torrential rain that turned the circuit into a quagmire, to the point that Senior winner Leo Tobin used a scrambles-pattern tyre on the rear of his Norton. A public-address system had been installed, as well as field telephones connecting the start area with marshalling points – a major boost to the safety of competitors and a big help for spectators, who struggled to identify the mud-covered riders. Previously, details of any accidents that occurred out of the sight of officials had to be passed on by the riders themselves.

However, this and other measures aimed at making the event safer did little to assuage the local citizenry, who were becoming increasingly vocal in their opposition to the races. The police were similarly disenchanted with the meeting, and it was only a concerted lobby from local businesses that kept the annual date in place.

The fact that the circuit was again awarded the premier title of Australian TT in 1936 resulted in a stay of execution. Tobin, very much the man of the moment, again won the Senior, with Bain second yet again, although he took out the Junior for the fourth time.

By 1937, speeds were rising to alarming levels, while the surface had further deteriorated from its usual appalling state. Once again, thick dust covered everyone and everything, contributing to numerous accidents, but after seven attempts, Don Bain finally took out the Senior TT to add to his four Junior titles. And although Art Senior failed to finish in the Senior TT, he set what would stand as the circuit’s all-time lap record – 6m11s, an average of 112.17km/h.

Clearly, the venue was unsatisfactory for many reasons, with speeds increasing year by year, the comical divided-road situation, and the ever-present dust. It was a disaster waiting to happen. But the lingering effects of the Great Depression meant that work was still hard to find in the mid-1930s, and the several thousand competitors and spectators who poured into the area each Easter were lifeblood to shopkeepers, hoteliers and guest house proprietors.

While one local group lobbied for the races to be abandoned on the grounds of safety and disruption to the community, another argued the economic benefits. However, the police were adamant they would not permit another race using the divided road, and the local enterprises issued a collective groan.

Fortunately, motorsport had a strong ally in the Mayor of Bathurst, Martin Griffin, a motorcyclist in his younger days who was also keen to bring car racing to the district. Griffin clearly recognised the positive financial impact of the Easter races to the community and was determined they should not be lost to Bathurst.

Just to the east lay a rugged area known as Bald Hill, with heavily timbered lower reaches, and Griffin had big plans for it. He had already hatched a scheme to construct a new, purpose-built venue and had even persuaded the Federal Government to pay for it, under the guise of an employment scheme for a ‘scenic drive’ – a term designed to appease the anti-motorsport lobby. The venue, he argued convincingly, would attract tourists to the city to picnic on the mountain, with its breathtaking views across the plains.

Griffin was quite adamant that there should be no break in the tradition of Easter motorcycle racing at Bathurst, so when the dust finally settled at Vale after the 1937 event, work on the new venue was already advanced towards the 1938 grand opening of what had been renamed Mount Panorama.

Words Peter Turner Photography Independent Observations