The return of the homologation special shows how a simple WSBK rule change can transform the bikes we ride

It’s said to be Soichiro Honda who originally coined the phrase ‘racing improves the breed’ and never has the influence of on-track activity on showroom models been as obvious as in the latest crop of new bikes launched for 2017.

Soichiro himself might have been pleased to see that his eponymous firm has recently unveiled a race-oriented, low-volume production bike – a typical ‘homologation special’ – in the form of the new CBR1000RR SP2. But the sudden spate of homologation specials also revives the endless question over production-based racing: does it truly prove which machine is best, or does it just encourage firms to create track-biased production bikes that are ill-suited to life on the street?

A quarter of a century ago homologation specials were the norm in superbike racing. Now a reversion to old-style regulations is responsible for their return. It might have seemed an innocuous thing when the WSBK rule-makers decided that, from 2016, entrants needed only make 500 examples of a bike for it to be considered a ‘production’ model and therefore eligible to race. That’s half as many as were needed to race in 2014 or 2015, and before that the minimum had been four times as high, with at least 2000 needing to be built.

Homologation production figures have regularly changed as WSBK regulations have evolved over the years, and for a long time there was a complex formula that allowed smaller companies to make fewer machines – sometimes as few as 150 was enough to enter. But the 2016 rules represent the first time since the blanket 1000cc capacity limit was introduced in 2003 that large-scale manufacturers have been able to enter bikes with only 500 made. In fact, they don’t even need to build them before they’re raced, as the 500-bike production figure need only be reached by the end of the second year of production. So, 250 bikes per year is all that’s required – it’s no surprise that manufacturers reckon they can get away with some rather high-priced, exotic machines.

A quick history…

As long as any form of racing has set requirements for minimum production numbers there have been manufacturers prepared to see what they can get away with. There’s no hard-and-fast definition of a ‘homologation special’, but whenever a bike’s production is limited to just what’s needed to be eligible, it probably qualifies for the term.

Even before the advent of WSBK, manufacturers were already playing the game. You can go back as far as the Suzuki GSX1000SZ, which appeared back in 1981 as sleeved-down, 998cc derivative of the normal 1100cc Katana to squeeze under 1000cc then-current superbike race regulations. But it was later, when four-cylinder superbikes were restricted to 750cc, and particularly when the WSBK started in 1988, that the craze really took off.

Given that the GSX-R750 stakes a claim to be the first modern superbike, it’s fitting that it formed the basis of an early homologation special, too. The GSX-R750 Limited Edition of 1986 set a template that many others would follow, with a dry clutch instead of the normal bike’s wet version, single-seat bodywork, uprated suspension and a standard steering damper.

But it was the Honda RC30, revealed in 1987, that remains the definitive homologation bike of the early WSBK era, and with good reason. Rather than bolting goodies to an existing production bike, Honda started with a clean sheet to create its beam-framed V4. Eye-wateringly expensive when new, it was still tempting enough to easily surpass the 500-bike homologation requirement, and went on to become a racing legend.

Others were fast to follow. Closest in spirit to the RC30 was the Yamaha OW-01, a ground-up design intended purely for racing. Its results never came close to the Honda’s, but road-going versions today are even rarer, since Yamaha stopped making them when the minimum 500 had been produced, and many went straight to race teams. Less exotic but still collectable was the early-90s Kawasaki ZXR750R, which came with a single seat, alloy tank and flat-slide carbs and was followed by a similarly-equipped ZX-7RR, which also gained an adjustable swingarm pivot and headstock. Suzuki kept playing the game too, with the delectable, 500-off GSX-R750RR of 1989 and later the GSX-R750SP.

Despite all these efforts, only Honda’s RC30 and its later development, the even more exotic RC45, were able to bag WSB constructors’ titles during the heyday of 750cc four-cylinder superbikes. Later, the V-twin Honda VTR1000 SP1 and SP2 also joined the winners list, but rival Japanese attempts stumbled. Why? Because whenever Honda wasn’t winning, Ducati was cleaning up with a host of homologation bikes of its own.

Delving into the history of Italian homologation machines is to enter a confusing rabbit hole of designations, specifications and blurred lines. That’s largely because smaller-volume firms – of which Ducati was certainly one during the 90s – had even lower homologation targets. At times, production of just 150 was enough to homologate a racer from small companies and on occasions even that target was waived by series organisers. Notable homologation Ducatis included the 851 SP models, SPS-spec 916s, and later ever-more exotic machines like the 955SP and the 996R. Aprilia tried a similar tactic with various derivatives of its V-twin RSV Mille, but with less success than its compatriot.

Even those are commonplace in relation to some, though. Near-forgotten homologation specials from the golden era of WSBK include many other unicorns. There was a host of Bimotas, from the 1988 YB4 that took Davide Tardozzi to victory in the first ever WSB race to the SB8K that Anthony Gobert rode to that stunning win at a drenched Phillip Island in 2000. And how about a Benelli Tornado Tre 900 Limited Edition, or the Honda SP2-based Mondial Piega that was developed for a stillborn attempt at the 2002 WSB series? Perhaps the ultimate oddity, though, was the Foggy Petronas FP1, with its bespoke 900cc reverse-cylinder triple. While there’s photographic evidence to prove that at least the initial 75 that the firm needed to build for homologation were actually made, they were never officially put on sale. Only in recent years have a couple of the bikes trickled into the public domain, with mystery hanging over their source and the whereabouts of the rest. It’s believed they are still under lock and key, and still owned by Petronas – which isn’t inclined to release them.

The glory era of homologation specials was largely killed off by the same regulation change that ultimately doomed the Foggy Petronas. In 2003, the year that the FP1 made its debut, the WSBK rules changed. While homologation-spec 750cc fours or 900cc triples were still allowed to race, the 2003-on rules also allowed 1000cc fours to race provided they met the much higher production figures needed at the time for SuperStock homologation. Even with the exotic technology they used, the smaller-engined homologation specials like the FP1 couldn’t live with the Fireblades, GSX-R1000s, ZX-10Rs and R1s that followed.

The new breed

When WSBK rule-makers slashed minimum production to 1000 in 2014, Yamaha’s engineers clearly pricked up their ears. They were putting the finishing touches on the all-new 2015-on YZF-R1 and realised that there was a good chance to sell a higher-spec version in great enough numbers to homologate some worthwhile changes. The result was the R1M, a machine that all the firm’s rivals have now responded to.

The R1M’s key elements include its electronics suspension, since the WSBK rules say: “Electronically-controlled suspension may only be used if already present on the production model of the homologated motorcycle.”

That gives the firm the choice of using electronic suspension or not, while if it wasn’t fitted to the R1M there would be no option but to use passive suspension.

Here’s how the new crop of bikes take advantage of the homologation rules.

1: Kawasaki ZX-10RR

The differences in Kawasaki’s race-ready version of the ZX-10R aren’t likely to make much of an impact on the street. But they will be useful for racers.

The cylinder head is altered, described as being ‘ready’ for high lift cams. Exactly what has been done isn’t clear, but WSBK regs provide strict limits on cylinder head modifications, and that’s surely why the RR version of the ZX-10 has got a different top end. It also gets DLC-coated tappets, which doesn’t sound like a big change but addresses a rule that says: “The shim buckets/tappets may be replaced but must be the same height, diameter, material type, surface finish and shim to top surface dimension as the homologated part.”

2: Honda CBR1000RR SP2

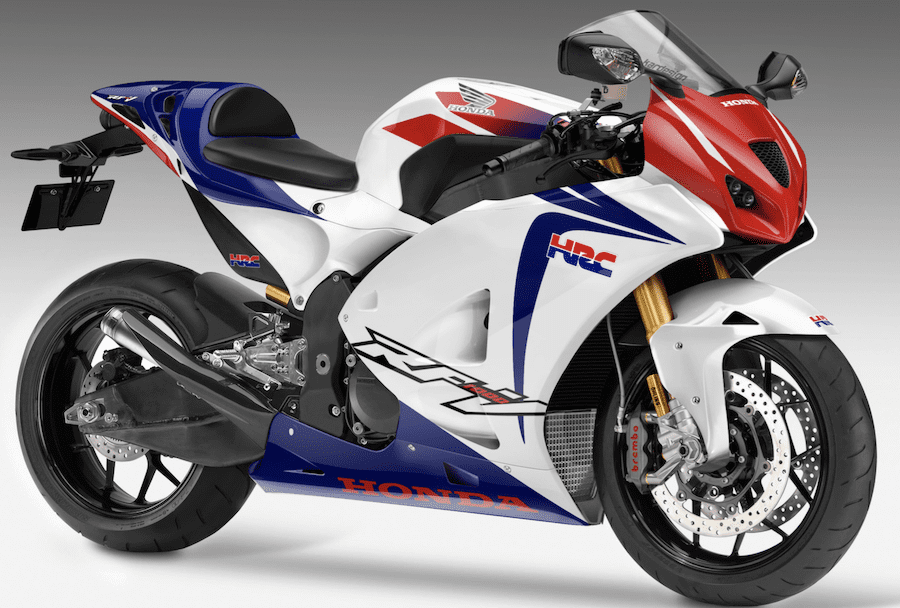

The SP2 version of the new Fireblade gets electronic suspension, like the R1M, to give it the option of using it in race form. The internal changes include larger intake and exhaust valves to address the rule that states: “Valves must remain as homologated.” The valve angles have been modified to address limits on cylinder head modification. And there are changes to the engine’s bottom end including the water jacket, because again these are components that aren’t allowed to be modified.

CBR1000RR SP2

3: Suzuki GSX-R1000R

While the ‘R’ version of the latest GSX-R1000 offers upgrades over the base bike in terms of suspension and electronics, they don’t appear to relate to homologation-limited components in a way to give the bike an on-track advantage in WSBK. But in time we wouldn’t be surprised to discover more, subtle changes to the ‘R’ model that come to the fore only when tuned to race trim.

Homologation wish list

RC30: It might not have been the first but the RC30 remains one of the most radical implementations of the idea. Throw in the fact that it was a resounding success on the track and it’s easy to see why road-going versions are now fast-appreciating collector’s items. In the end, far more were built than homologation required

.

RC45: All the attributes of the RC30 plus even lower production numbers and more technology. The fuel injection feels jerky by modern standards, particularly in town where the bike’s also hamstrung by its madly-long 140km/h first gear. But get it out on a flowing road and you can’t fail to be stirred.

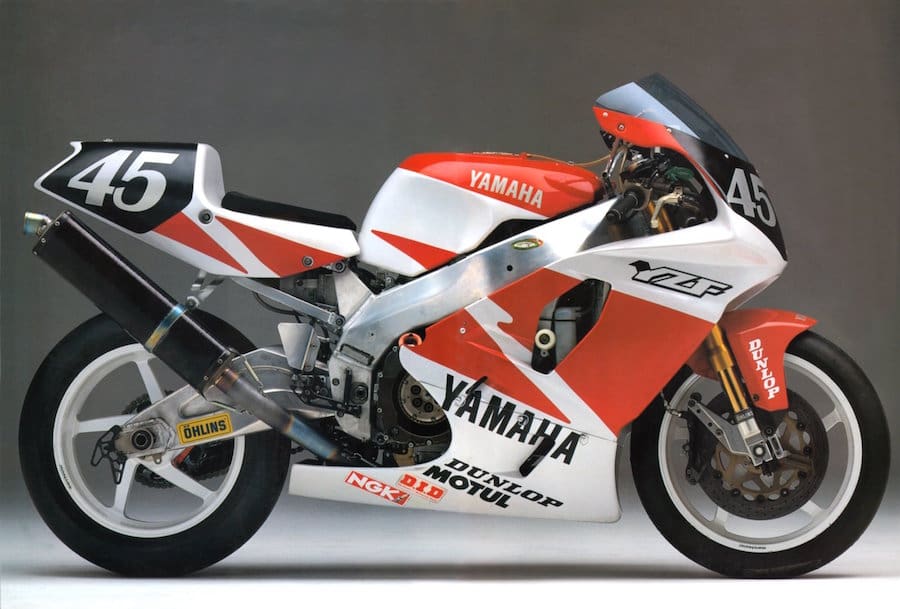

OW-01: The FZR750R OW-01 never had quite the success of the RC30 but remains a legend regardless. It was more than twice the price of an FZR1000 Genesis when it was launched, and featured kit including titanium rods, but never managed to get a WSBK title despite many race wins. Today prices are close to RC30 levels and only going in one direction.

OW-0/YZF- R7: Appearing in 1999 the R7 was an all-out last effort by Yamaha to create a 750cc four to win in a championship that was by then heavily favouring 1000cc twins. Only 500 were made and after a poor debut season it was good enough to allow Noriyuki Haga to challenge for the championship in 2000. Haga’s banned-substance drama and the race he missed as a result eventually gifted the title to Colin Edwards and Honda, and Yamaha left the championship at the end of the year. The R7’s career was short-lived and tumultuous, but the remaining roadbikes still command witheringly high prices.

Under the radar

If the prices being asked for RC30s and OW-01s are making you consider one of the latest generation of homologation specials as an investment opportunity, it’s worth noting that not every racetrack refugee has gone through the roof in terms of value.

But if you’re buying, it’s a bonus, as machines that were largely hand-made competition specials are available at a surprisingly low price if you look in the right places…

Aprilias RSV Mille SP: Even compared to more famous Japanese homologation bikes, the Mille SP from 2000 is a rare beast. The firm’s size meant it only needed to make 150 of them for homologation. It might look much like a normal early RSV, but the engine has a different bore and stroke and new heads courtesy of Cosworth. There’s a new frame, too – stiffer and more adjustable than stock – and all-carbon bodywork. These days they’re half the price of an RC30 or OW-01, as it seems people have forgotten how impressive the bike was when Troy Corser rode it to third in the championship in its sophomore season after a development year with Peter Goddard riding.

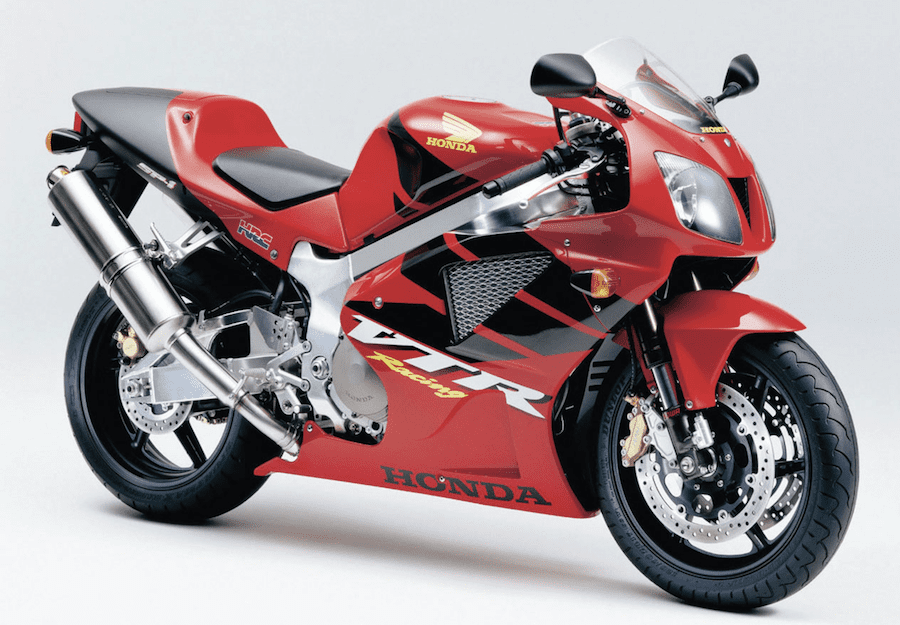

SP1s and SP2s: It’s a riddle as to why one set of title-winning, HRC-branded homologation Hondas – the RC30 and RC45 – cost a small fortune while the subsequent pair, the VTR1000 SP1 and SP2, go for next to nothing despite just as much on-track success. Sure, they’re not as rare, although numbers are thinning as time passes, but at around A$6000 for an average one, they seem a bargain. Surely its time the market reassessed these gems. Differences between the SP1 and SP2 are minor; the earlier bike is arguably more collectable, the later one is the better ride. On either (but particularly the SP1) you’ll want to sort the over-stiff rear suspension.

YZF-750 SP: The direct descendent of the OW-01 might not have been quite as exotic but it’s still got the typical race-spec kit of its early-90s era flatslide carbs and multi-adjustable suspension, for instance, plus a close-ratio box and single-seat tail. As with the OW-01, it was made in minimal numbers. Prices are far, far lower, though – around a third as much as a similar-condition OW-01 or R7.

Benelli Tornado Tre 900 LE: If you want a bike that has a glittering WSBK race history, move along, but the ‘LE’ version of the Tornado was the original run of carbon-clad, Öhlins-suspended, Marchesini-wheeled, titanium-piped Benellis following Andrea Merloni’s revival of the brand. It had all the homologation essentials including an adjustable steering head angle and formed the basis of the bike Peter Goddard would ride in the 2001 and 2002 WSBK championships. LE models aren’t plumbing the price depths of base-model Tornados, but if you can find one, they’re comparatively cheap for their spec and rarity (150 were made). New, they were A$65,000, now around A$25,000 should bag one. Only two were originally sold in Australia, though.

What next?

Although it’s not yet green-lit for production, we know Honda is already developing an even more focussed bike to fit the latest homologation rules (see AMCN Vol 65 No 24). A V4 superbike based around the RC213V-S engine in a totally new cast-aluminium chassis, it’s being developed in much the same mould as the original RC30.

If it reaches production – and our sources say that remains a hot topic of discussion within Honda – the bike will be even higher-spec than the new CBR1000RR SP-2. However, it will still have to meet the €40,000 price limit (A$57,000) that WSBK imposes on the production version of any bike that competes in the series.

WORDS BEN PURVIS PHOTOGRAPHY AMCN ARCHIVES