MotoGP’s much-hyped new aero fairings are the beginning of a whole new area of development. We assess the factory fairings, with insight from a Formula 1 car aerodynamicist

Last year’s MotoGP aerodynamic revolution was bolt-on winglets. Now, in 2017, the real aero race has begun.

Protruding winglets were banned last autumn on safety grounds. Some riders called them “knives on the side of the bikes”, others complained that the dirty air behind a heavily winged MotoGP bike threw any motorcycle in its wake into a 200-miles-an-hour tankslapper.

Those who thought the ban was the end of the aero race were in for a shock, but they shouldn’t have been because MotoGP bikes have a problem – they approach take-off velocity on the fastest straights, so they need downforce to keep the front wheel on the road. In other words, they’re pretty much as dangerous without wings as they are with wings.

Increasing front downforce improves high-speed stability, but the main aim of MotoGP aerodynamicists is to reduce wheelies during acceleration, for faster lap times. MotoGP anti-wheelie software is very basic, so it cuts torque too aggressively, which hurts acceleration. Extra downforce keeps the front down to keep the anti-wheelie silent.

Yamaha was the first team to show its 2017 aero, at Sepang in January, but most people were waiting for Ducati’s answer to the new regulations. The Italian factory kept its 2017 creation under wraps for ages, finally unveiling it shortly before the season-opening Qatar GP. It didn’t disappoint.

Iannone’s (and Suzuki’s) aerodynamic wing fairing

Ducati has led MotoGP’s aero race for a decade or so, ever since it employed former McLaren F1 engineer Alan Jenkins. Last year the team was way ahead of the game, the Desmosedici featuring different aerodynamics set-ups at different tracks.

The GP17’s downforce fairing is as radical as it gets, and may take MotoGP aerodynamics down a whole new road, although these are early days, with most factories declining to use their new aero at the season’s first races. Nevertheless, it’s going to be an interesting ride, according to aerodynamicist Ali Rowland-Rouse.

“Ducati’s new aero is a step-change in design, it’s changed the game overnight,” says Rowland-Rouse, who works on Formula 1 and Le Mans Prototype aero projects during the week and races a Triumph 675 at weekends. “It’s going to be interesting because motorcycles are infinitely more complex than F1 cars.

“A lot of calculations are based on the centre of gravity position, which stays in the same place on an F1 car, but not on a bike. Motorcycles are really difficult because the centre of gravity is always moving. Plus there’s also a lot more feel involved in riding bikes. It’s about getting the set-up right for each rider – it’s not all cold, hard physics. If you fed Marc Márquez’s riding technique into a computer, the computer would say ‘does not compute!’”

Dovizioso’s new aerodynamic winglet fairing, Qatar MotoGP test, March 2017

Although straight-line aero is the current aim, there may also be improvements to be found in cornering grip, but this is a tricky game to play because too much downforce can be disastrous when riders attack corners.

“If you make a motorcycle downforce device that acts straight through the centre of the tyre contact patch when you’re upright, as soon you’re leant over you increase the lateral acceleration, which is what your tyres fight against, so you reduce tyre grip,” explains Rowland-Rouse. “So it’s all about weighing up the effectiveness of an aero device in straight lines and in corners.”

Indeed, excessive downforce at the wrong time and in the wrong place has caused a few crashes over the past year or so. Like everything in racing, it’s a fine line.

Aprilia racing manager Romano Albesiano explains: “You must be careful about how much downforce you create because you have to apply load to the [Michelin] front tyre very delicately,”

These crashes at least confirm that aero bodywork does have an effect on cornering behaviour of the bikes.

“Last year there was no doubt that the wings worked because teams noticed that even with the more basic set-ups there was extra load on the front through corners,” says Rowland-Rouse. “This didn’t just reduce wheelies but kept the front tyre better planted.”

Sometimes so heavily planted that the tyre smeared away from under the bike, putting the rider on his backside.

Hopefully, the new aero will be safer than last year’s winglets, but MotoGP’s efforts to exorcise aero costs have obviously failed. From now on all MotoGP factories will be spending a lot of money on development in this area, with CFD (computational fluid dynamics) and wind tunnels.

Ducati Desmosedici GP17

Ducati Corse boss Gigi Dall’Igna was angry when winglets were banned, so you can imagine his delight when his aerodynamicists showed him their subsequent work. The GP17’s so-called hammerhead shark bodywork does what engineers are supposed to do – push the rules to the very limit. And it’s done more than that; the radical design had jaws dropping up and down pitlane because none of the other factories had expected anything like this.

The GP17’s upper fairing looks like an on-board stereo system, sans speakers. Ducati has cleverly worked its way around the rules to create four ‘wing’ surfaces within the bodywork.

And it works, up to a point. “The new fairing works very much like last year’s winglets,” says Andrea Dovizioso, who used the fairing during pre-season tests more than new teammate Jorge Lorenzo. “I’m very happy with the results, because without winglets it’s very difficult to create the downforce you need to get stability from the front end. But there is always a negative, this time in the middle of the corner, so it’s always a balance. At a track like Qatar, with a long straight, the negatives were bigger than the positives, but for sure we will use this fairing during the season, maybe at Jerez, which is one of our bad tracks.”

Ducati did not homologate the hammerhead for the Qatar GP because it wanted to modify the design before confirming it as one of the two new designs allowed during 2017, in addition to one wingless 2016 fairing.

“This new fairing shows how hard we have worked in the wind tunnel,” says Ducati sporting director Davide Tardozzi. “It provides about half the downforce to the double-wing sets we used at some tracks last year, but with the speed and power of MotoGP bikes we are forced to work in this direction and change the bodywork to suit each track. For sure we will keep exploring in this direction, and we will soon homologate a refinement of this design.

- Lorenzo, Argentinian MotoGP 2017

- So far Dovi has been the only one to test the hammerhead design – and both he and Lorenzo have raced with the standard fairing

“We did not race it in Qatar because this was not the racetrack for this fairing. During pre-season tests at the track the data told us that we were losing around 8km/h on top speed.”

Ducati did not use the hammerhead in Argentina either. Still, Rowland-Rouse is highly impressed with Ducati’s original thinking and the team’s knowledge of aerodynamics.

“The important thing is that they’ve got a good separation between the upper and lower surfaces,” he says. “You get high pressure above a wing and low pressure below, so you don’t want those forces interacting.

If the surfaces are too close, the low pressure generated by the underside of the upper surface affects the high pressure of the lower surface, which reduces downforce.

“The design is quite ‘draggy’, so it will probably come and go at different tracks,” adds Rowland-Rouse. “We do a lot of this in F1; we simulate an entire lap with each aero design, which tells us how much we gain in each corner and how much we lose on each straight, then you add it all up to see what works best at each track.”

Ducati has cleverly worked its way around the rules to create four ‘wing’ surfaces within the bodywork

Aprilia RS-GP

Aprilia’s first go with the new rules is the odd one out. The downforce section of the RS-GP’s new upper fairing looks more like a NACA duct, a kind of cooling duct used in car racing since the 1960s.

It cannot provide much downforce but may turn out to be the cleverest design of the lot because Aprilia believes it may provide the best compromise between maximum downforce and minimum drag.

“Aerodynamics is all about the ratio between downforce and drag efficiency,” says Aprilia race chief Romano Albesiano. “I think our system has a very good potential because we get a downforce advantage with almost no

extra drag.

- Sam Lowes at Argentina, running the standard fairing

- Romano Albesiano, Spanish MotoGP 2015

“We did not use the fairing at the first races because we had too many other things to fix. Our test team will work on the fairing and we will bring it back in two or three GPs. The game has just started … as soon as one manufacturer finds the best way to exploit the potential, the others will follow.”

Rowland-Rouse struggles to see the potential of the RS-GP fairing but is sure it must have something going for it.

“It’s a refrained solution – a duct with a small vane inside – and I can’t see it being a particularly strong solution,” he says. “But it’s got to be doing something because this kind of development costs a lot of money, so wouldn’t have gone to this effort without having its efficiency confirmed.”

Aprilia’s aero is the odd one out: the downforce section of the RS-GP’s new upper fairing looks more like a NACA duct

Yamaha YZR-M1

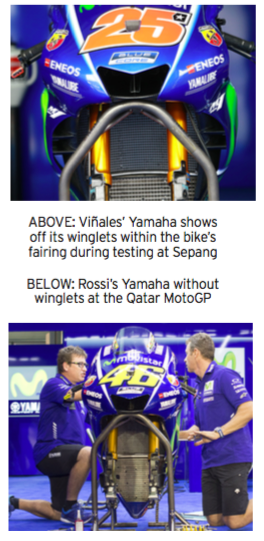

Yamaha’s 2017 aero design is the most elegant solution, with two aero vanes inside each side of a widened fairing.

The bodywork is less radical than Ducati’s, but still only suits some tracks. Yamaha didn’t use the fairing in Qatar or Argentina for the same reason most factories didn’t – the extra downforce was too much of a negative on the long main straights and through the numerous direction changes.

“At the Sepang pre-season tests the new fairing was better because there are no really fast corners and not so many changes of direction,” said Maverick Viñales. “But somewhere like Losail or Phillip Island, there are many fast corners and changes of direction and a lot of wind. All these things make the bike really heavy to turn, so I cannot attack corners.

“The aero fairing helps a little bit in acceleration by keeping the front really down, so it will be an advantage at tracks like Le Mans, where there are many slow corners, so the bike is always doing wheelies.”

Rowland-Rouse is impressed by the Yamaha’s integrated design: “It’s a neat little solution, but the effect will be less than what they had last year.

“They’ve presumably looked at the maximum fairing width, then put a couple of vanes in there, then they’ve run the fairing skin around the outside of the vanes. I’d say the gap between the two vanes is too small because the two surfaces are really close to each other, so the low pressure beneath the upper vane may interfere with the high pressure [for downforce] of the lower vane. On the other hand, it’s probably more efficient in terms of drag than last year’s wings.

“Also, the endplate [the fairing skin] will massively reduce the vortex that would come off the end of the wings, so the instability for a following rider won’t be anywhere near as bad as it would be with conventional wings.”

Honda RC213V

Surprisingly, Honda’s first 2017 aero effort was the most basic of the lot; surprising because this is a company that’s been involved in Formula 1 for decades and now manufactures jet planes!

“This looks like a bit of an afterthought,” says Rowland-Rouse. “It’s a standard fairing, with a skin wrapped around last year’s wing. The skin is a carbon-based rapid prototype [made using a 3D printer]. We use this system a lot in F1; if we need a part at the last minute we churn it out and put it on the car.”

Honda’s first solution didn’t work well; Márquez crashed in testing and blamed the accident on the aero.

“The fairing gives less wheelie but makes bike the little bit heavier to turn, so I didn’t like the feeling,” the World Champion said. “But we must work on it because when we tried the first wings last year they made the bike too heavy, but then they changed the shape and they were better. Maybe we will use the new fairing at the Jerez GP. I’m hoping for a surprise.”

Honda’s effort may not look high-tech, but now they know where the aero race is going. It will be interesting to see what they come up with next.

Suzuki GSX-RR

Suzuki’s aero is halfway between the Honda and Yamaha creations. The team has wrapped a skin around a 2016-type wing, like Honda, but has managed to do it more elegantly, like Yamaha. But does it do any good?

Suzuki’s new number one rider Andrea Iannone isn’t that impressed.

“We have compared data between the normal fairing and the ‘wing’ fairing and they are more or less very similar,” he says. “There is just a small advantage in wheelies, but not so much, and the bike becomes worse in changes of direction.”

Despite Iannone’s downbeat assessment, Suzuki was the only factory to race its aero fairing in the season-opening Qatar GP. Maybe the design is the ideal compromise, for the time being at least…